Omnivorous Reader

Portrait of a Rock Icon

The good, the bad and the ugly

By Stephen E. Smith

When organizing the 1967 Monterey Pop Festival, the promoter phoned Chuck Berry to invite him to perform, explaining that the acts were donating their fees to charity. Berry replied, “Chuck Berry has only one charity and that’s Chuck Berry.” End of discussion.

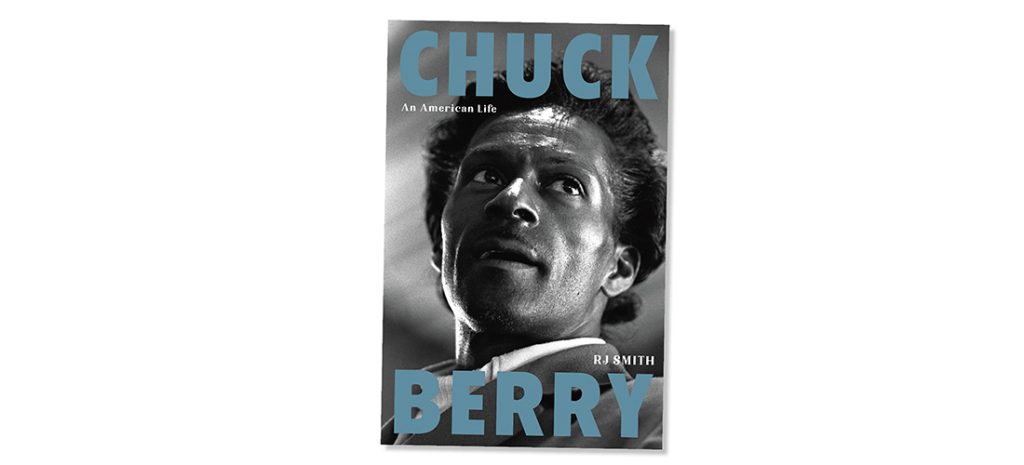

That was Chuck Berry at his most generous, and readers of RJ Smith’s Chuck Berry: An American Life will likely be taken aback by the unsavory details of the life of the man who gave us “Maybellene,” “Roll Over Beethoven,” “Sweet Little Sixteen,” “Back in the U.S.A.,” “Reelin’ and Rockin’,” “School Days,” “You Never Can Tell” and “Johnny B. Goode,” rock ’n’ roll classics that pop culture will not willingly let die.

Smith’s biography has been widely lauded in print, online and over the airways, and his study of Berry’s life is as close to a complete examination available to the public. Court records offer even more objectionable details. This much is certain: The more you read about Chuck Berry’s lifestyle, the less likely you are to ever listen to “Maybellene” with a sense of nostalgia.

Berry grew up in a solid middle-class St. Louis family. He wasn’t a blues guy who spent his youth picking cotton and banging on a catalog guitar. He did, however, suffer discrimination early in his life, and Smith devotes the opening chapters of the biography detailing the effects of Jim Crow on Berry’s formative years.

Berry’s trouble began when he was convicted of armed robbery as a teenager and spent almost three years in juvenile detention. When he was released, he drifted into music, became an early master of the new electric guitar, and created an original sound by combining country music with boogie-woogie.

We can argue about who invented the concept of “rock star,” but certainly Chuck Berry, Elvis Presley and Jerry Lee Lewis could lay claim to the term. Berry’s shtick was to sing with impeccable diction while blasting glib rapid-fire lyrics that teenagers could instantly comprehend and dance to. This straightforward blueprint for early rock ’n’ roll attracted Black audiences in the early ’50s. By the mid-’50s Berry’s fanbase was integrated. In the 1960s, he was playing to almost entirely white crowds, at which point his performance was simply called “rock.”

The bulk of Smith’s biography is taken up with the upsetting stories that accompany Berry’s hundreds of performances. His business plan was straightforward. Berry would sign a contract with a promoter who was responsible for supplying the backup band and amplification equipment. He’d arrive in a Cadillac, also supplied by the promoter, minutes before he was to take the stage. There’d be no rehearsal, no interaction with the band, and he’d demand payment in cash before performing. Berry would count the moola, play for the designated amount of time, duckwalk for the audience’s edification, and bang out the hits for which he was best known. Then he’d exit the stage. If there was an encore, he’d demand additional cash. When the concert was over, he’d pack up his guitar and make a clean getaway.

Generally, the audience loved it, dancing, cheering and having a fine time. Berry made money, the promoter usually made money, and the audience left satisfied. The late Rick Nelson summed it up best in his hit “Garden Party”: “Someone opened the closet door and out stepped Johnny B. Good,/playing guitar like ringing a bell, and looking like he should.” Ray Kroc would have been proud — Berry cooked up musical cheeseburgers, each one a tasty clone of its predecessor. Consistency was the key.

All of which was fine and dandy with American audiences. But there was one overawing problem: Chuck Berry. He was irascible, mercurial, essentially unknowable, and had an affinity for trouble. After serving his time in juvie and achieving fame as a rock ’n’ roller, he began traveling the county with a 14-year-old Native American girl he claimed was his assistant. The cops weren’t buying it and nailed Berry for violating the Mann Act — transporting an underage female across state lines for immoral purposes. He spent two more years in prison. Then the IRS began tracking the cash Berry received for his performances and nailed him for income tax evasion, and late in his career he was busted for installing covert cameras in the restrooms of a restaurant he owned, an act of voyeurism that gave rise to an investigation that uncovered a trove of pornographic material in which Chuck Berry was the star.

As Berry’s antisocial behavior was becoming common knowledge, he was being roundly honored by the American public. On Whittier Street in St. Louis, the National Register of Historic Places listed his home as a monument, and after his release from prison for violating the Mann Act, NASA blasted gold-plated recordings of Berry’s “Johnny B. Good” into interstellar space aboard Voyagers 1 and 2. (Voyager 1 is now 14.1 billion miles from Earth, a far distance from the prison cells Berry occupied in the ’60s and ’70s.) His IRS indictment was greeted with a universal shrug, and his voyeurism conviction was likewise ignored by the press. Chuck Berry went right on performing and raking in the big bucks, playing out the string until the bitter end.

Smith has included all the facts: the good, of which there’s little enough; the bad; and the ugly, of which there’s plenty. Two questions remain. First, who was Chuck Berry? Did anyone truly know the man? Berry explained his sense of self in an interview: “This is a materialistic, physical world. And you can’t really KNOW anybody else, man, because you can’t even really know yourself. And if you can’t know yourself then sure as hell no one else can. Nobody’s been with you as long as you and you still don’t know yourself real well.”

The second question is more complex, encompassing the American penchant for revering individuals, whether rich, talented or charismatic, who are given to violating legal and social norms. Are we willing to accept outrageous behavior from unrepentant religious leaders, corrupt politicians and wayward rock ’n’ roll stars because they’ve somehow made themselves infamous? Apparently so. After all, nothing is quite as American as hypocrisy. OH

Stephen E. Smith’s latest book, Beguiled by the Frailties of Those Who Precede Us, is available from Kelsay Books, Amazon and Local bookstores.