Saint James Presbyterian Church has been serving God and the Gate City for 150 years

By Grant Britt • Photographs by Lynn Donovan

“God is so great that anything we would come against, even if you have to silence us, the very blood, our very life would still preach after that. — Rev. Diane Givens Moffett, Ph.D.

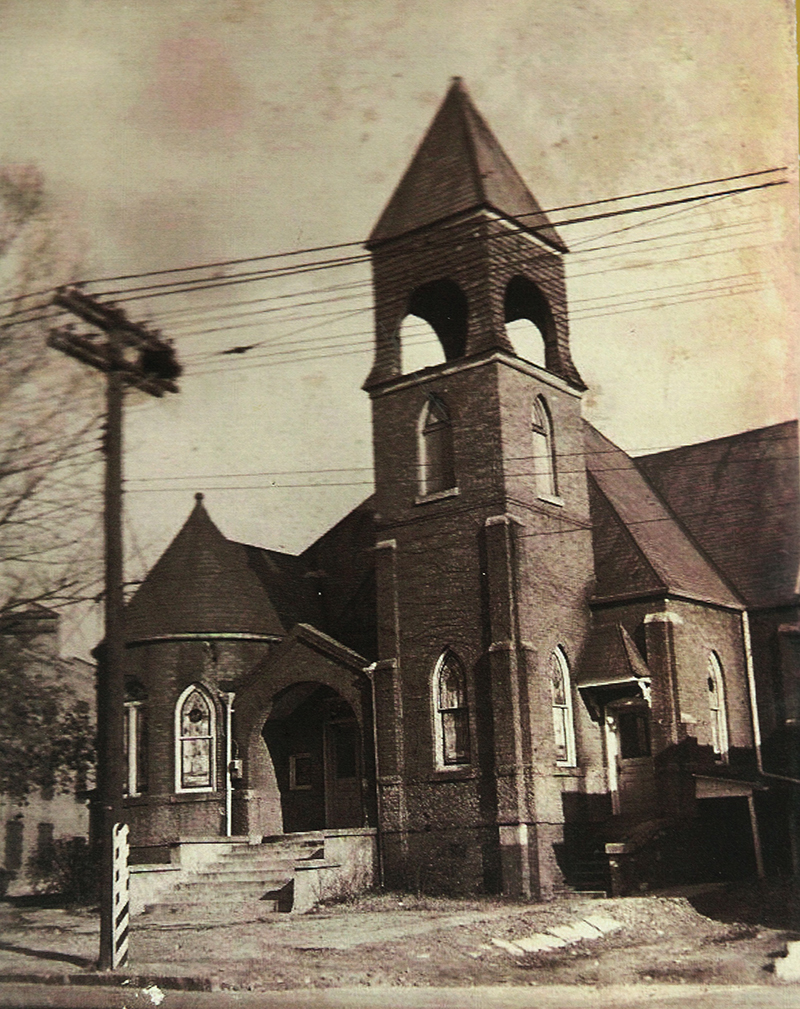

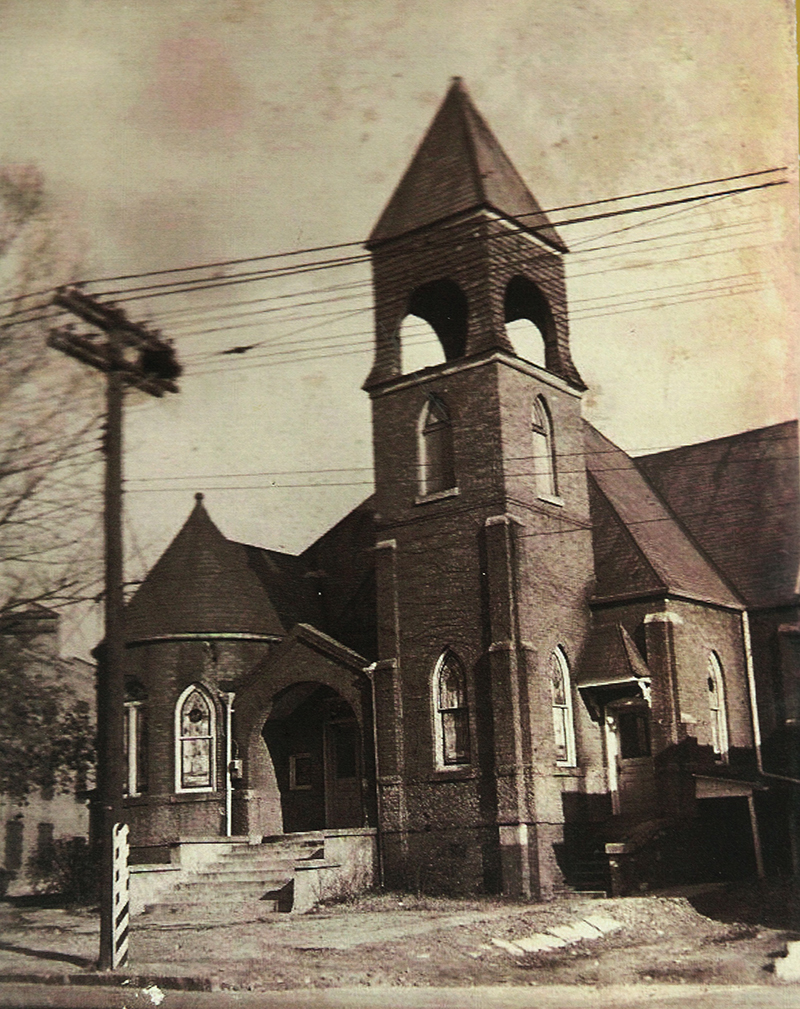

It’s a beacon of hope, a monument to overcoming oppression, celebrating a century and a half of black pride and African-American accomplishment. Founded by slaves in 1867, Greensboro’s Saint James Presbyterian Church is much more than just a house of worship. From its inception, it’s given strength, purpose, education, awareness, and healing to its members and the community.

“When the church was founded 150 years ago, there were people who had just recently been freed,” says Lolita Watkins, chair of the church’s 150th Anniversary Activity Book and Historic Kick-Off event. “They were worshiping up in the balcony at a local church, First Presbyterian,” Watkins says of the church’s founders, who moved to a new church with little fanfare. “At some point, they decided to move on and didn’t tell the folks at First Presbyterian they were going. The pastor and the elders looked up and they weren’t there anymore. The folks said, ‘It’s time for us to get outta here,’ and they did.”

Watkins’ research reveals that the newly formed church’s first pastor was a Lexington-based minister named Crestfield. “His name was James,” Watkins says. “The thing is, we don’t know if they thought they were naming it relating to the Bible, or the name of their first pastor.”

Within a year of their first assemblage, the tiny congregation of a little more than 30 souls had bought a small house on Forbis Street (now Church Street). By 1872, the church had outgrown its original home, dismantling the house and building a larger, wood-framed church on the site with an additional parsonage next door.

Even in those early days, the church was already providing more than just worship services. Around 1870, Saint James had established the Percy Street School, the first black school in Greensboro. It was a one-room setting accommodating 150 men, women and children. Realizing that the decided space was too cramped, church elders asked the state board of education for support in in building a larger school. “The Percy School was called the first graded school,” adds Lynette Hawkins, publicity chair for the 150th anniversary committee. “There were no other schools for African Americans.”

Watkins says there was some private tutoring done at another African-American church, but this was a public school facility. “The founding principles of the church were education, naturally; civil rights, and social justice.”

Ever since then, Saint James members have been actively involved in civil rights and social justice issues on a local and national level. In December 1955, George Simkins, a local dentist and head of the local NAACP chapter, was arrested when he challenged the city-owned Greensboro’s Gillespie Golf Course’s contention that it was a private course and therefore could refuse membership or entry to anyone. Convicted of simple trespass and fined $15, plus court costs, Simkins, along with five golfing buddies branded the Greensboro Six, took the case all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court and had their sentences commuted by Gov. Luther Hodges. The city closed the facility until 1962, when it reopened as an integrated course. Simkins also took on Cone Hospital and Wachovia Bank’s segregation policies and won.

Watkins cites other church members involved in civil rights actions including James McMillan, an art instructor at Bennett College who advised students during the time of integration at Woolworth’s lunch counter sit-ins. He also co-founded the African-American Atelier in the Greensboro Cultural Center, with church member Eva Hammond Miller, Congresswoman Alma Adams and others.

Another church stalwart, attorney J. Kenneth Lee, was nicknamed the Thurgood Marshall of North Carolina because of his involvement in more than 100 court cases having to do with civil rights. “He was the founder of American Federal Savings and Loan, one of the first lending institutions in the state of N.C. designed to help African-American families who were routinely denied loans to buy houses or cars here in Greensboro,” Watkins says. “One of the first African Americans to finish law school at UNC-Chapel Hill, he had to use the courts in order to be admitted.”

Watkins also mentions Dr. George Evans, a local doctor who was one of the first blacks to be appointed to Greensboro Housing Authority, very active locally in civil rights, as well as John Brown Erwin, another church member who was vice president of the NAACP for 42 years. “The church still supports NAACP in terms of their banquet and monetary contributions, “ Watkins says.

Among the roster of noteworthy congregants was Robert Tyrone “Pat” Patterson, who took part in the 1960 Woolworth’s sit-in. Patterson and a group of fellow N.C. A&T students, Joe McNeill, David Richmond, Ezell Blair and Franklin McCain, were studying for a chemistry exam when a boycott of Pepsi-Cola taking place in Wilmington came up in conversation, inspring the students to come up with the idea of a similar boycott in Greensboro. “I thought that it was a kind of half-hearted kind of decision and didn’t think any more about it until the next day,” Patterson told interviewer Eugene E. Pfaff in a 1989 Greensboro Public Library Oral History Program interview: “I was on my way to an electrical engineering class when they passed me going to class, indicated they were going downtown to sit-in. I said, ‘Fellows, I really don’t have time to just go downtown to drive around if you are not going to do it.’ Obviously I didn’t believe they would do it. So they went down and they did, they sat-in at Woolworth. And I guess the next day was when I got involved directly. We started demonstrating at that time, and did a lot of demonstrating.” Patterson was vice chairman of the Congress of Racial Equality chapter in Greensboro in 1963.

Among the roster of noteworthy congregants was Robert Tyrone “Pat” Patterson, who took part in the 1960 Woolworth’s sit-in. Patterson and a group of fellow N.C. A&T students, Joe McNeill, David Richmond, Ezell Blair and Franklin McCain, were studying for a chemistry exam when a boycott of Pepsi-Cola taking place in Wilmington came up in conversation, inspring the students to come up with the idea of a similar boycott in Greensboro. “I thought that it was a kind of half-hearted kind of decision and didn’t think any more about it until the next day,” Patterson told interviewer Eugene E. Pfaff in a 1989 Greensboro Public Library Oral History Program interview: “I was on my way to an electrical engineering class when they passed me going to class, indicated they were going downtown to sit-in. I said, ‘Fellows, I really don’t have time to just go downtown to drive around if you are not going to do it.’ Obviously I didn’t believe they would do it. So they went down and they did, they sat-in at Woolworth. And I guess the next day was when I got involved directly. We started demonstrating at that time, and did a lot of demonstrating.” Patterson was vice chairman of the Congress of Racial Equality chapter in Greensboro in 1963.

Church members and college professors Ernest and wife Adnee Bradford also played a prominent role in the civil rights movement. While serving as a Presbyterian minister in Selma, Alabama, in ’62, the Bradfords participated in the anti-segregation activities of that era. “My husband graduated from Morehouse College,” Adnee Bradford says in a recent phone interview. “He came under the influence of Benjamin E. Mays, then president of Morehouse, who would influence my husband, Martin Luther King, and almost everybody else who went to Morehouse.” She continues the thread: “When my husband and I were dating, he was saying Dr. Mays encouraged Morehouse men not to participate in any system that dehumanized them. So my husband would not take me to the Fox Theatre in Atlanta for any reason, because it was segregated, and black people had to climb these high stairs to go into what Ernest called ‘the buzzard roost.’” It was an epiphany for Bradford, who says, “from that time on, I realized my husband was very aware of racism. He believed there were things we could do in order to help get rid of it or certainly not participate in our own dehumanization.”

“He was an activist,” Bradford says. Her husband joined with Dr. King, attending meetings when the Selma NAACP was planning the march to Montgomery. “But we were also tying to desegregate the system in Selma so that black people could vote. And my husband actually went to jail. He participated in the march that Sunday that’s become known as Bloody Sunday. I remember that Sunday when Ernest left, and when he came back home, he was just distraught because of what had happened on that bridge,” she says, her voice trembling with emotion as she recalls the pain and degradation inflicted on the marchers that day. “And he named people who were knocked down, Mrs. Amelia Boynton, for example.” Boynton, who was the first African-American to run for a seat in congress from Alabama, was beaten unconscious on the Edmund Pettus Bridge on March 7, 1965. The nationally distributed picture of her lying bloodied and senseless on the bridge over the Alabama River in Selma that Sunday was a critical factor in pressuring President Lyndon Johnson to enact the Voting Rights Act in August of that same year, with Boynton as the guest of honor at the signing ceremony.

Although her husband was on the front lines, Bradford was behind the scenes at first. “I taught at the all-black high school, Hudson High School in Selma,” she says. “Our students were participating in the marches, they were attending the mass meetings and they saw Dr. King when he came to town, and they were telling it to us when they’d come to class. And I can hear myself saying to the students that what they were doing made a difference, but they were not to neglect their education. All of us as teachers, we’re in the schools teaching, and the kids are out there in the streets.”

The head of the local NAACP at the time, Rev. Frederick D. Reece, was a math teacher whose classroom was just across the hall from her classroom. “The day came when the question was, ‘What are the teachers doing?’” Bradford says. “We weren’t out there because we knew any one of us going out could have easily been fired. But Rev. Reece wasn’t afraid to be out there.”

Reece called a meeting of the segregated Selma Teachers Association, appealing to the teachers to take a stand by marching to the Dallas County Courthouse. “His emphasis was ‘in numbers there is strength,’” Bradford says. “And so we agreed. We marched after the school day had ended. And I remember all day long as faculty, as we passed each other we would say, ‘Do you have your bag ready?’ Meaning, do you have your toothbrush and do you have a change of clothes, ’cause we thought we might just go to jail,” she chuckles nervously. “And so we marched. And we did not go to jail. And that became kind of a historic moment in Selma for the teachers.”

The Bradfords came to Greensboro and Saint James in ’76, when Adnee was hired to teach at Winston-Salem State University. Her husband continued his activism. “My husband became involved with Nelson Johnson and the Beloved Community and the Greensboro Truth and Reconciliation Project,” she says. The 2004 GTRC consisted of an independent panel of seven, nominated by the community, to investigate the November 3, 1979, Klan/Nazi and Communist Workers Party confrontation that left five dead and 10 injured in the Morningside Homes community during a “Death to the Klan” demonstration. “At the time of his death in 2009, he was still involved in the struggle with human and civil rights,”Bradford says.

In April, as part of the church’s 150th anniversary celebration, Dr. Bradford led a discussion that accompanied the 2015 documentary Selma: Bridge to the Ballot, about the part students and teachers played in Selma striving for voting rights. It brings back vivid memories of the indignities she and others suffered in Selma in those days.

“I went back to Selma in 2014 for the commemoration of the Edmund Pettus Bridge, for that Bloody Sunday. All I remember about Selma is that it was a segregated town, blacks really had no rights. We lived in a segregated community, could not vote. I remember the treatment of black people, the segregated stores, the way we were treated when we went to the stores downtown, the way white folks looked at us,” she recalls.

She says a recent PBS broadcast talked about the Montgomery bus boycotts and why they were successful made her think about what might have been possible in Selma. “Black people really have supported through the years segregation, have supported a racist system just by being alive. And those folks in Montgomery were successful in that boycott, so in Selma, we needed to have done the same kind of thing.”

But she still carries the memories and the principles earned so dearly in those early days. “I know how we would fold hands and sing ‘We shall overcome, always, always.’ And somebody was talking about not being able to be nonviolent, and I said, ‘Well, Dr. King never had people go into the streets willy-nilly.’ There was always some preparation in going out, in terms of being nonviolent, and the songs and the sermons and the messages that were heard, all a part of the strategy to carry marches, to go and to take the abuse leveled against them, even as they protest — a peaceful revolution.”

But in spite of its activism and drive, in early 2000 the church felt that it needed some new blood to help it continue to grow. The older movers and shakers needed some young energy to reach out to young adults, to rejuvenate and reactivate the principles on which the church was founded. Reverend Diane Givens Moffett, Ph.D. got the call in 2005, and answered.

Moffett, a 20-year pastoring vet from California, heard about the opening from Saint James member Margie Ward. “I felt God calling me to come here almost 11 years ago in June of 2005,”she says. “My specialty was evangelism and discipleship. I had grown churches, I was the type of person who would come in and do renewal or transformative ministry, see what the possibilities were and try to realize them.”

But there was one major question that needed answering. “I wanted to make sure they were open to the challenge to call a woman because my dossier stood out, but they would always come back with ‘but she’s a woman, should we do this?’” she laughs. “It was a bold stand to call the first woman, because I’ve been first in every place I’ve been. It was a good match. God has done a lot of wonderful things here,” she says.

Moffett says she knew the church had a history of civil rights involvement and cultivating strong ties with the community, but wasn’t aware of just how deeply the church’s roots were entwined in the movement. “Did I know particular people like George Simkins and Dr. George Evans and all these people we have featured in our Achievers and Believers Book? No, but I knew that the church was a beacon of light in terms of mandating social change.”

The pastor says when she started thinking seriously about coming to town, she started researching Saint James. “I learned it was formed by freed slaves that left First Presbyterian Church Greensboro in 1867 and I thought ‘Oh, these are bold, these are edgy people.’”

She was impressed as well as with that first congregation’s decision to start a school. “The church from its very inception understands the wholeness of our humanity, not just spiritually, but economically and socially,” Moffett says. “Not only did they have the church, they developed a school for the freed slaves who needed to know how to negotiate this new territory. That’s in our spiritual DNA,” she asserts. “Activism, impact on community. We’re not a church that sits and turns inward. We’re a church that understands that the church was formed to make a positive impact on the community.”

To that end, Moffett and church leaders have been consulting with community leaders to implement programs to help. Their vision is three-pronged. The first part addresses renovations to the church to give easier access for the elderly and disabled. The second phase is to establish a community center, the third, a child development center.

Saint James partners with Cone Hospital to achieve some of those goals (Moffett is on the board of the Cone Foundation) and has engaged a congregational psychiatric nurse who works with those needing help with mental-health issues. The church also feeds their bodies as well as their souls. “We call them our guests, our neighbors, those who are homeless, economically disadvantaged,” Moffett says. “Every Sunday we have a hot healthy meal, don’t fill ’em up with carbs and things that are not healthy for them. Make sure that people who need access to care have it.”

In Saint James’s fellowship hall, others in need can also sit down to a hot meal. “We have our bus, we’ll go pick them up. Sometimes they’re down at the Urban Ministry, Interactive Resource Center; we go get some, some bring themselves, some are coming on bicycles, some walking from Martin Luther King Street, some driving themselves, some coming with children,” Lynette Hawkins says. “We’re really just connecting with people who need to be fed. What I have learned is that there are a lot of people out here hungry. Greensboro is a major area when it comes to providing those kinds of resources, so once they have hooked up with it, they are friends for life, really feel connected in some way.”

Education is also a key issue. The church is publishing a book, Achievers and Believers, and coordinating a book tour with Waldo C. Falkener Sr. Elementary and George Simkins Elementary schools, among other Greensboro primary schools. The book tour includes trips to the homes of those who contributed to the city’s history, as well as a trip to Vance Chavis Library, named after another church member.

“We are in partnership with Falkener Elementary School when they have any kind of special needs,” Lynette Hawkins says. “They were recently doing some kind of testing, so we had volunteers go and help them” There’s also a box at entrance to the church where people donate school supplies for teachers who work at Falkener. “We are very sensitive to the needs of the community, and we really try to look at where we’re gonna donate so we can help move it further.”

In addition, the church partners with Cone for the MedAssist plan, giving over $1000,000 worth of medication to more than 1,080 people who came to the church last year to get over-the-counter medicines. Moffett says that economically disadvantaged and/or homeless often don’t have the money to buy the over-the -counter medicines that could help cure a cold or deter it so it doesn’t go into something worse. “Basically this organization has the resources to be able to get things that might have been at one of the pharmacies. They’re not expired but maybe the box is a little torn. Those thing were given away and people filled the sanctuary multiple times to line up in our fellowship hall and get free supplies,” says Lynette Hawkins. “Our theme is ‘Touching lives through Jesus Christ. We’re aware there are so many needs, medical needs, educational needs, our focus is to try and identify those things.”

And once the physical needs are met, Moffett has to lead her flock through the current political climate as well, promoting a sense of hope and encouragement against what may seem at times to be insurmountable odds.

“We’re celebrating our 150th anniversary. We’ve always had to deal with insurmountable odds so let’s not get it twisted here,” Moffett says heatedly. “We came over here in crisis. We came over here not because we emigrated, or migrated as some books want to say, believe it or not, people are saying we migrated, forced migration, right? We came over in crisis, and we come from a history of very strong people who overcame with a lot less than we have today, so my issue is, I tell my congregation we’ve got to work like everything depends on us, pray like everything depends on God, but we’ve got to be active in our community.”

And in the spirit of activism the church is known for, Moffett speaks out against would-be oppressors. “Time to make our voices known, to stand with those who are hurt by some of policies that have been implemented. It’s a time for the church to be the church.”

“There’s always hope,” the pastor says. “ When it’s dark, the light shines even brighter. We’ve got to be able to move forward, help people to register to vote. I served as vice president of pulpit forum and also co-chair of Greensboro Interfaith Leadership Council. We really are working on standing with immigrants and refugees who are as scared as I don’t know what right now. We’re standing with people. The LGBTQ community, we have to stand with people. My understanding is that God is concerned about EVERYONE. And NOBODY’s humanity, I don’t care who they are, is up for disposal. Or to be disregarded. This is not what we do. We create a healing environment for everyone. That’s what I preach and hope.”

The message comes from above, but what goes on down below can help spread some of that light around. “Eternal life is not just for the sweet bye and bye,” Moffett asserts, “but for the nasty here and now, it’s about a quality of life right here. So I encourage our church by my own example as embodying it, to touch people’s lives.”

She continues: “But let us understand that everyone who ever did anything, including these people: George Simkins, Martin Luther King, when they were going through it, it was tough. Now, years later, you apologize and it’s celebrated, but while you’re going through it, it’s no fun. We’ve seen God do amazing things,” Saint James’ fiery pastor says. “I’m always hopeful.” OH

Grant Britt writes about churchy as well as secular matters, his hilltop perch across from a graveyard keeping him humble.

Among the roster of noteworthy congregants was Robert Tyrone “Pat” Patterson, who took part in the 1960 Woolworth’s sit-in. Patterson and a group of fellow N.C. A&T students, Joe McNeill, David Richmond, Ezell Blair and Franklin McCain, were studying for a chemistry exam when a boycott of Pepsi-Cola taking place in Wilmington came up in conversation, inspring the students to come up with the idea of a similar boycott in Greensboro. “I thought that it was a kind of half-hearted kind of decision and didn’t think any more about it until the next day,” Patterson told interviewer Eugene E. Pfaff

Among the roster of noteworthy congregants was Robert Tyrone “Pat” Patterson, who took part in the 1960 Woolworth’s sit-in. Patterson and a group of fellow N.C. A&T students, Joe McNeill, David Richmond, Ezell Blair and Franklin McCain, were studying for a chemistry exam when a boycott of Pepsi-Cola taking place in Wilmington came up in conversation, inspring the students to come up with the idea of a similar boycott in Greensboro. “I thought that it was a kind of half-hearted kind of decision and didn’t think any more about it until the next day,” Patterson told interviewer Eugene E. Pfaff