A Writer’s Life

Revenge of the Lawn

Covet not thy neighbor’s grass. Just go hire the right organic lawn care specialist

By Wiley Cash

Iím standing on my lawn in Wilmington, North Carolina, recalling the time I heard a mindfulness teacher condense the many years of the Buddha’s teachings into one sentence: Cling to nothing as I, me, or mine. That’s good advice, life-making or life-changing advice depending on when you receive it, but it’s hard advice to follow in my neighborhood, especially as my gaze drifts from the weed-choked, shriveled brown grass at my feet to the lush, pampered golf course-green of my neighbors’ lawns. All around me are weeds I don’t understand, things I’ve never seen before, things I never could have imagined: monstrous tendrils that snake into the air in search of something to strangle; vines covered in thorns and bits of fluff that cling to the skin like the pink fiberglass insulation your dad always warned you not to touch in the attic; scrubby pines no taller than 6 inches with root systems as long as my legs and twice as strong.

Roughly 250 miles west sits the city of Gastonia, where I was raised in a wooded suburb that always felt to me as if the houses in the neighborhood of my youth had been forged from the landscape. In my memory, dense forests loom in our backyard, the smell of wood smoke curls through the air, grass looks like grass: thick blades that grow up toward the sun instead of clumping and crawling like desperate snakes wriggling toward prey.

Another 100 miles west, nestled in the cradle of the Blue Ridge Mountains, is the city of Asheville, where I grew into adulthood and made the decision to become a writer. This meant I worked odd jobs and lived in relative — if not romantic — poverty throughout my 20s. I inhabited a slew of rental houses with friends of similar ages and similar interests, each house having one thing in common: a wild expanse of unkempt lawn where nature grew in a heady, beautiful containment — variegated hostas, blue and pink and purple hydrangeas, English lavender and flame azalea. We didn’t water anything or spread fertilizer. The only people who ever cut the grass were the landlords, and that was done sporadically with the weather and season. Yet, it seemed that we could have dug our heels into the black earth and something beautiful would have sprung forth.

Down here on the coast my lawn is nothing but sand with a thin skin of sod draped over it. I live in a region where if you buy plants at the garden store, you’d better buy the soil to plant them in. Nothing but the most tenacious, native weeds can survive in this boggy, sandy soil. Some days I have doubts about my own survival. It too often feels like I don’t belong here, but then again, my lawn doesn’t belong here either. Just a few months before we moved in, this landscape was marked by piney swamps dotted with ferns, maples and the occasional live oak. Not long ago, bulldozers plowed through and pushed over all but a few of the pines. Then dump trucks flooded the wet spots with tons upon tons of fill dirt. The developer carved out streets, piled the dirt into 1/4 acre squares, and called them lots. The builder began constructing houses. Finally, landscapers rolled out strips of St. Augustine, punched holes in the ground and dropped cheap shrubs into the earth.

My wife and I bought one of the first lots, and there were only a handful of houses in the development when we built ours. We moved in just in time to watch nature attempt to reclaim its domain. We’ve been here almost four years. Now, the streets bubble where swamp water pulses through cracks in the asphalt. The drainage ponds are full of alligators that behave more like residents than those of us who have built homes. At dusk, tiny bloodthirsty flies, what the locals call “no-see-ums,” dance in the night like specters, biting your ears, eyeballs and neck.

And then there are the weeds. The canopy of trees is gone now, and the weeds have ample sunlight and plenty of room to spread.

I lie in bed at night pondering the use of industrial-strength fertilizers and weed killers, and I weigh their environmental destruction and the health risks they pose my children with the possibility of having a lawn of which I can be proud. I begin to empathize with companies responsible for accidental coal-ash spills (Everyone wants electricity!) and incidental pesticide contamination (Everyone wants bananas in January!).

Deciding to forgo potential carcinogens, at least for now, I appeal to someone who seems expert in all things related to lawns and manhood. Tim lives three houses down and has the most perfect yard in the neighborhood. He’s tan and tall and lean. He could be 40 or 65, the kind of guy who rides his road bike to the beach each day at dawn with his surfboard strapped to his back, the kind of guy who looks like Lance Armstrong or Laird Hamilton, depending on whether he’s wearing spandex or board shorts.

I find Tim watering his lawn with a garden hose. The rest of us turn on our irrigation systems and hope for the best. Not Tim; he waters like a surgeon. He’s barefoot, and I wonder what it feels like to be able to walk shoeless in one’s yard without feeling the sharp crinkling of dead grass blades beneath your feet. I explain my lawn problems to him, at least insofar as I understand them. He listens with patience, perhaps even sympathy.

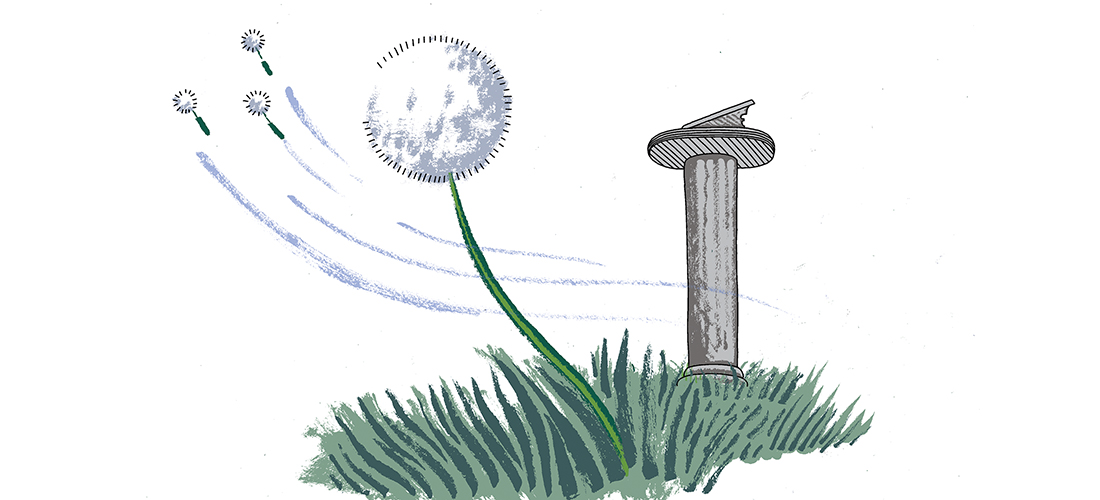

“Fertilize,” he finally says. “Organic. Commercial. Whatever. It doesn’t matter. And then wait until it rains.” He turns off his garden hose and finds the one weed in his yard that’s apparent to the naked eye: a dandelion that looks more like a flower than any flowers I’ve planted in the past year. Tim reaches down and plucks the dandelion from the earth with the ease of lifting it from a vase. “They come up easier when the ground’s wet,” he said. “Roots and all.”

So, early in the spring, I fertilize the yard with liquid corn gluten meal. The air smells like a combination of popcorn and barnyard, but it seems to have enough nitrogen in it to green up the grass. And, after the next rain, I pull weeds. For hours. It works. By early summer my lawn is green and nearly weed-free, but I never get too comfortable.

I’m out of town one morning when I text my wife and ask for an update on our lawn. I receive a photo reply within a few minutes. I hesitate to open it the way young people hesitate to open report cards, the way old people hesitate to open medical tests: There’s nothing I can do about it now, I think. To my surprise the photo my wife sent shows a vibrant green lawn dappled with early morning dew. I can’t help but wonder if she’s walked up the street and snapped a picture of Tim’s grass. Regardless, I allow relief to wash over me: The C- I’d been expecting has become a B, the heart disease diagnosis I knew awaited me has ended up being indigestion. Life can go on as long as it rains — but not too much — and the sun keeps shining, but not on the west side of the lawn because there is no shade there, and if we don’t get enough rain the grass will crisp up pretty quick.

Late in the summer the grass begins to turn brown in strange semicircles, and when I look closely I can see the individual blades stirring. I kneel down and spot a tiny worm at work. I look closer, spot hundreds, no, thousands more. Our neighborhood has been invaded by armyworms. Instead of spending my time on the novel that’s months overdue, I spend a small fortune coating the grass in organic neem oil. To make myself feel better about not writing I listen to podcasts about writing, but my attempt to stave off writer’s guilt is just as futile as my attempt to fight the armyworms. Our green grass is eaten away within a matter of days; my soul follows suit, and I can only hope both will re-emerge come spring.

But that spring, something else happens instead. In May, my father is diagnosed with an inoperable brain tumor, and the lawn and its calendar of fertilizing and hydrating slips from my mind. He passes two short weeks later, and as I ease into grief the summer spins away from me, and I don’t even look around until August, when my yard comprises more weeds than grass. I’ve missed the opportunity to fertilize, and there’s no amount of safe weed killer that’s going to make a dent.

I wait for it to rain. Then I fall to my knees, and I pick weeds.

My 2-year-old daughter joins me. Sometimes she’ll yank up fistfuls of grass because it comes up easier than the weeds. I don’t have the heart to correct her, and I can’t help but wonder if she’s on to something. How long would it take us to tear out all this grass and start over? I look at my neighbors’ thriving lawns, and I assume that the pain of death or responsibilities for children or work-related obligations have not touched their lives in the ways they’ve touched mine. If only my life could be as clear and clean and healthy as their lawns appear to be.

This year, I decide that I don’t have the patience, the faith, the head space, or the heart space to battle my lawn, and I call a local company that specializes in organic lawn care. I’m surveying the yard when the technician arrives. His name is Steve, and he’s actually the owner, which puts me at ease. He’s middle-aged, clean-shaven with glasses and silvery hair. He speaks quietly, confidently. I can’t help but think that he senses something about me. Perhaps he knows that I’m embarrassed to admit that I can’t do something as simple as grow grass, that I’ve put too much pressure on myself, that things have gone too far, that I’m clinging to something that does not deserve my clinging.

In my recollection, he puts a hand on my shoulder. Maybe he even takes my hand. He leads me around the yard, whispering the names of the weeds he finds, the ways in which he can stop them. He tells me it’s not my fault. It’s hard to grow grass in this environment, especially in new neighborhoods like mine where the sod hasn’t had time to take root or an existing organic structure to give it life. And my ground is too hard, he says. It needs to be aerated. It needs to be softened.

We agree on a treatment regimen. They’ll start next week, provided it doesn’t rain.

“You’re going to have a beautiful lawn,” he says. “You’ll be happy.”

“I appreciate that,” I say. “But it’s all yours now.” OH

Wiley Cash lives in Wilmington, North Carolina, with his wife and their two daughters. His forthcoming novel The Last Ballad is available for pre-order wherever books are sold.

The first time

The first time