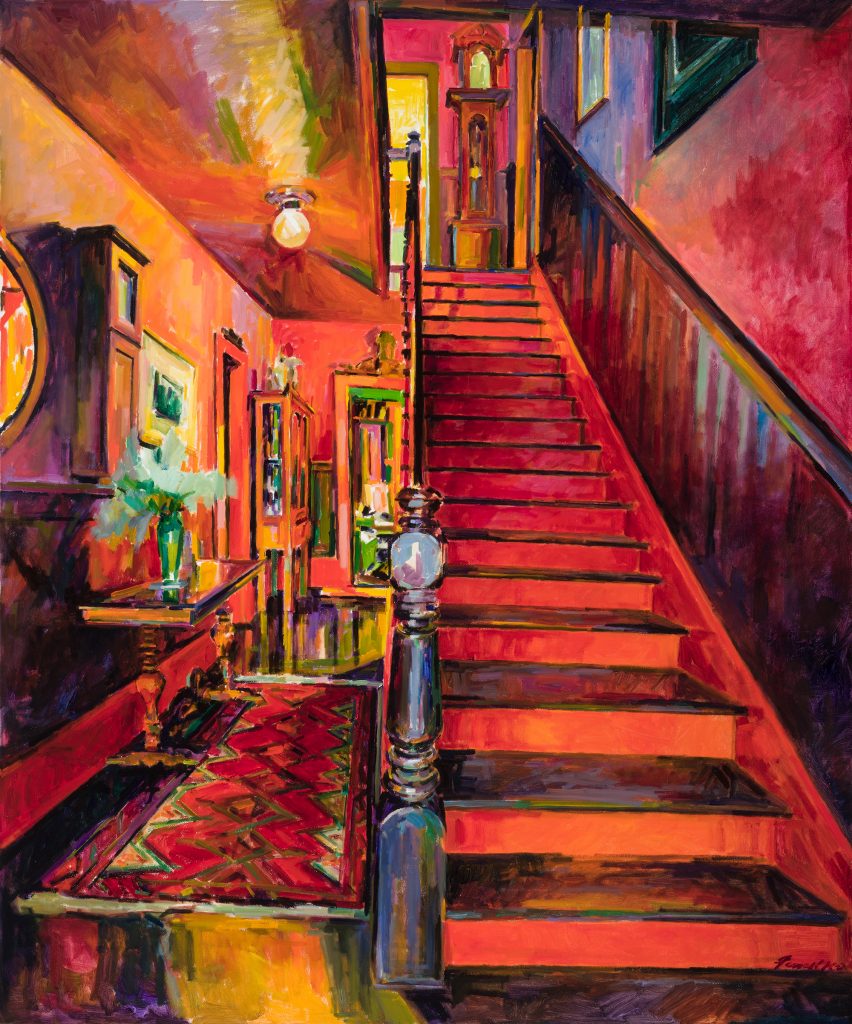

Chasing the Elusive

A conversation with artist Richard Fennell

By Maria Johnson

Hanging around Greensboro’s GreenHill art gallery just before an opening,

Richard Fennell looks like a collector who’s arrived early.

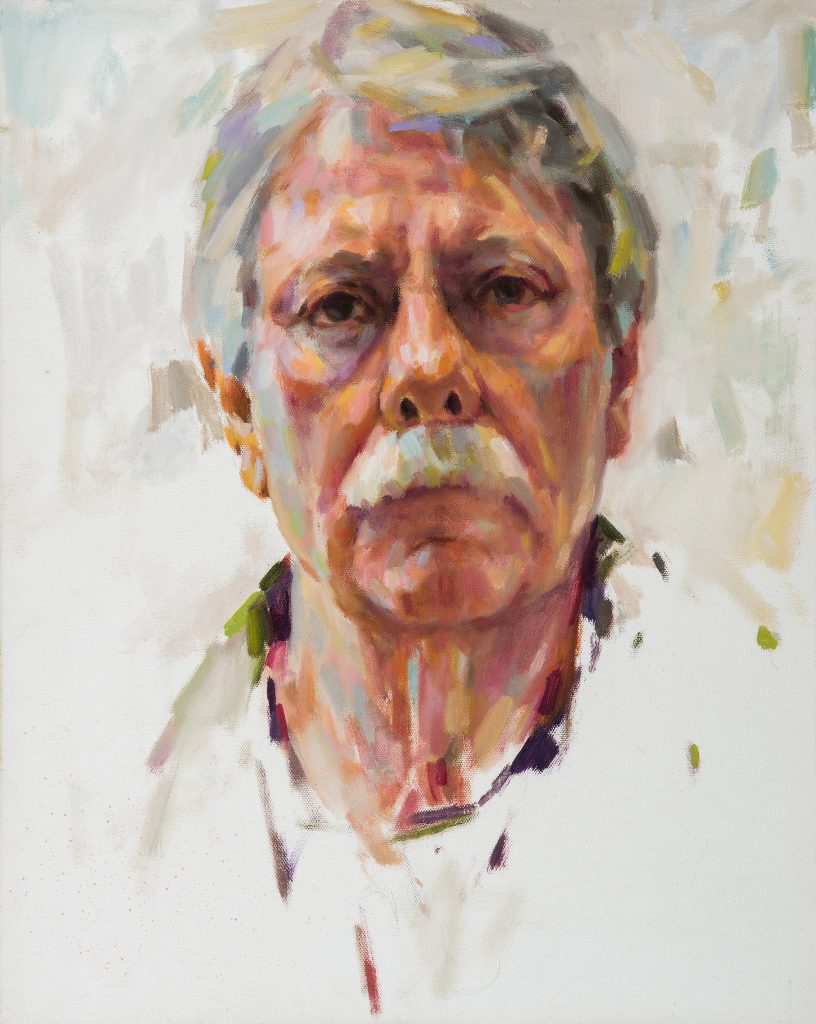

Well-groomed and white-haired, he’s the model of business casual. You could be forgiven for wondering: Is he a retired corporate lion waiting to pounce on the cash bar? Perhaps a senior partner who helped his law firm build an impressive collection? Or maybe he’s a local politico?

That would be sort of true. Fennell’s serving his sixth term as the mayor of wee Whitsett (population 600ish) on the eastern edge of Guilford County.

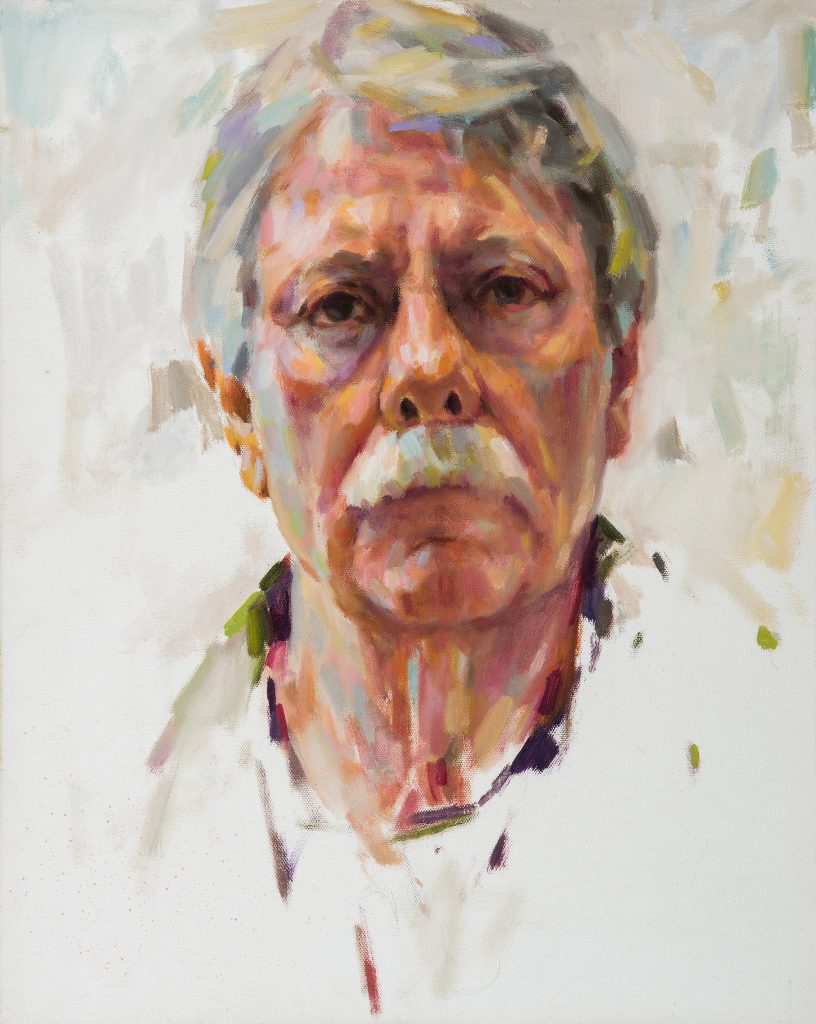

But you’d be closer to bingo if you noticed that this mustachioed gentleman favors a couple of portraits on the wall: self-portraits of the artist.

Yup. Same guy. Which means that beneath the municipal exterior beats the heart of an artist — an artist’s artist — whose work is the stuff of GreenHill’s ongoing show: The Edge of Perception: Richard Fennell Retrospective.

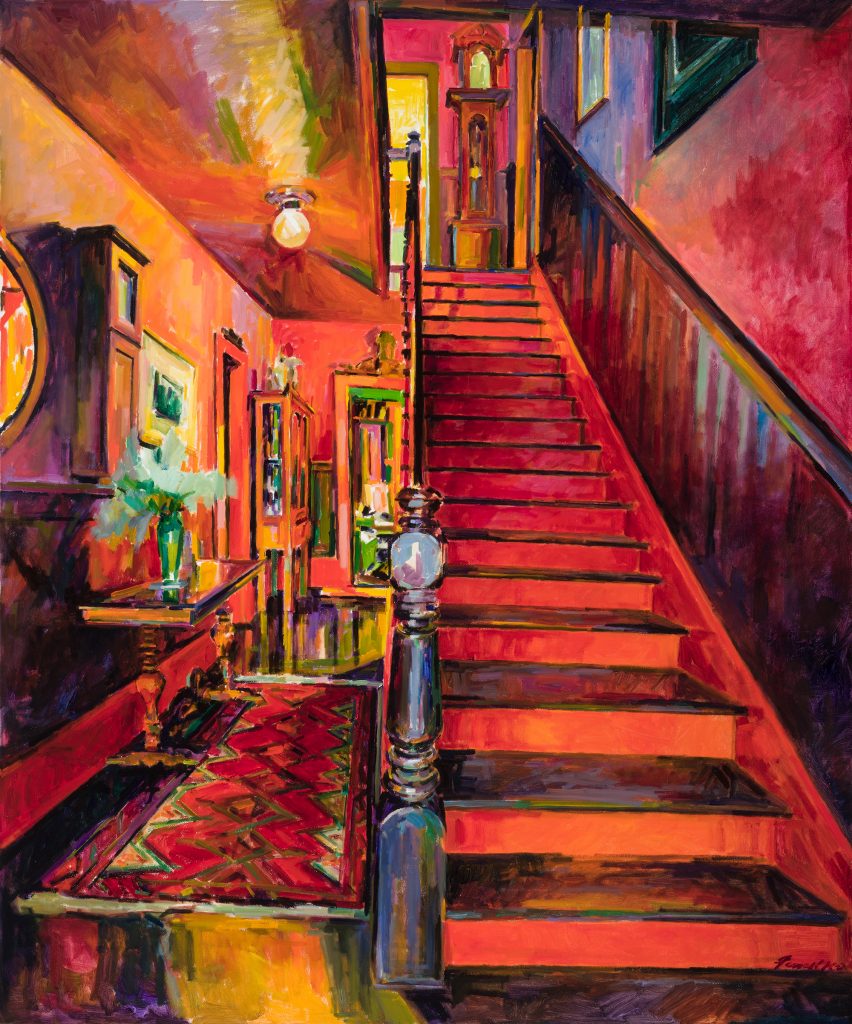

The exhibit — more than 100 works plucked from a 50-year career — shows Fennell’s evolution from his undergraduate days of etching and printmaking at East Carolina University, through the formative years he spent getting a Master of Fine Arts degree at UNCG.

As a student of the so-called Greensboro School at UNCG, he was introduced to the painterly use of color, which he married to a lesson from sculpture — the importance of studying the space next to an object, or “looking off the edge,” as he likes to say.

Fennell, now 70, got noticed while he was at UNCG. He landed a piece in the North Carolina Museum of Art. Since then, he’s become one of the state’s most successful painters, with hundreds of pieces hanging in homes, museums and corporate offices around the Southeast.

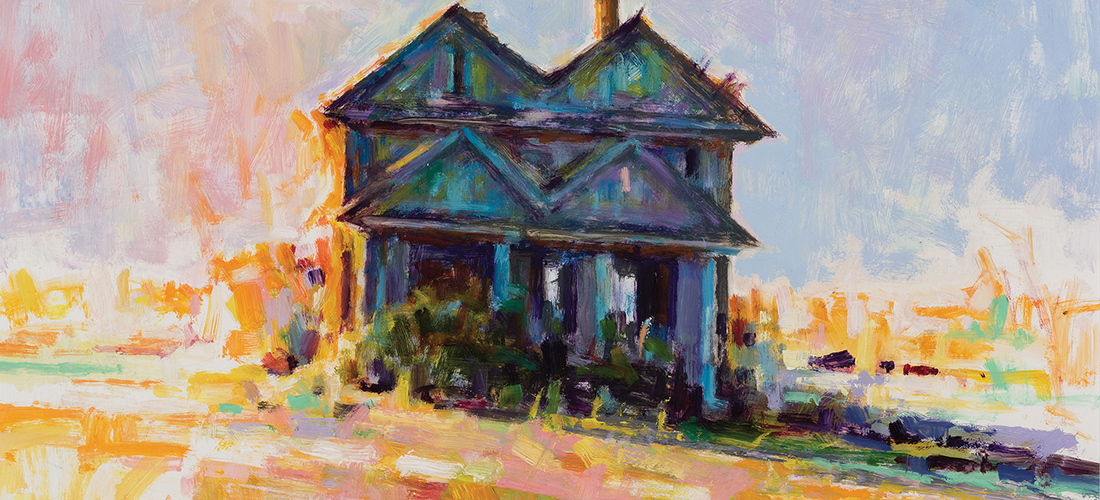

Known for his color-rich still lifes and rural landscapes — rendered mostly in oil and sometimes in pastels — Fennell’s a crowd-pleaser in the vein of his favorite painter, French Post-Impressionist Paul Cézanne.

He has painted all over North Carolina, including coastal marshes, Piedmont meadows and farmhouses, and mountain vistas near the home he built by hand in the Ashe County community of Grassy Creek.

Like any lifelong artist, Fennell has tussled with his craft, tinkered, solved, relaxed, understood and repeated the process over and over in his quest to capture “it.”

In an interview just before his show opened, he explained what “it” is and why he’s still nipping at its heels.

He’ll give art fans a further peek into his thinking when he conducts a painting demonstration on August 16, 6–7 p.m., at GreenHill. The exhibit runs through August 20.

MJ: Has your work always been so colorful?

Fennell: No. I started off in black and white. I was always interested in drawing. When I was an undergraduate, I started in printmaking and painting. Later on, I was really able to understand color.

MJ: What brought you to that understanding of color?

RF: It started with sculpture and watercolor. I studied with Peter Agostini, who was a sculptor, and he got me started on that idea of trying to develop the form within the space it existed. I was working three dimensionally with clay. Also, I did drawings and watercolors. I learned early on, watercolor is direct. You have water and you have color. The water will stretch the color. You can have it very intense and bring it down. There are many subtleties, and I began to really understand color at that point. When I went over to oil, it was a totally different medium and didn’t act anything like watercolor, so I just started using pure color. When I wanted a red, I’d use a red, when I wanted a pink, I’d use a pink.

MJ: You were applying patches of pure color?

RF: Right. Then another thing I was doing — and I learned from sculpture — is when you’re building a form, you’re applying the clay, but you’re also tearing down. With oil, I started doing the same thing: I’d apply it and look at it. I’d also tear it down. If it wasn’t right, I’d scrape it off and work back into it. Then you start getting layers of color.

MJ: Most people don’t think of oil paint as being dimensional.

RF: Right, but working on a flat, two-dimensional space, it’s totally different from working in the round with clay. With your working on a flat space it’s really difficult to get that feeling of solidity and form. So a lot of times it takes this [he gets out of his chair and ducks and weaves as if he’s looking at canvas from different angles].

MJ: How would you describe the Greensboro School? What were some of

the hallmarks?

RF: To me, it had some truth to it. When I studied in undergraduate school, it was all Abstract or Abstract Expressionism, Pop Art. This was in the late ’60s, early ’70s. That didn’t really appeal to me, so I started looking for something else. When I was looking into grad schools, I saw UNCG was totally different. I saw these beautiful figures that people were drawing and painting. And I was like, “Wow, I’d like to understand what they’re doing.”

MJ: So that would be a unifying theme for the Greensboro School, an emphasis on figure?

RF: Right, and working from life. That’s how you learn about color, that’s how you learn about just about everything. It’s not a photographic type of understanding of reality. It’s not like I’m copying “it,” but I’m trying to understand “it” and I’m trying to reconstruct “it.” “It” is that elusive thing that’s out there, and that probably comes down to truth — and a life force.

MJ: Is there anything else that would pop out as a common thread for the Greensboro school?

RF: Color was probably one, too. Andrew Martin, I learned a lot from him about color.

MJ: Once you came into your style, and you recognized that people liked it, did you ever feel hemmed in by knowing that there was commercial value in painting that way? Were you ever scared to go off in a new direction or try something different?

RF: Yeah, I was. A lot of times, you get that from galleries. One time I was doing some work, and they said, “People like your old work better,” and I was like, “What the hell? I don’t care about that.” That makes you mad. That’s when you go and do something really off the wall. But sometimes, you do feel like you’re falling into that trap, especially when galleries are telling you, “People like this.”

MJ: So how have you pushed yourself?

RF: A lot of it has to do with where you are. That kind of dictates what the outcome is going to be. I’ve never been one of these artists who had to travel, say out West, because I feel like I have so much information where I am.

That’s the nice thing about working from life, is that you see things that you could never imagine. I saw something the other day I’d never seen before. I was looking at a landscape and I saw a space far in back, then I saw the light hitting fairly close, then I saw something in-between that I’d never seen before. It was the way the light was falling. It was hitting bits and pieces of things, maybe the tips of vegetation, and it created almost this movement sandwiched between the two spaces I was looking at. That was really exciting. I was like, “Wow, I gotta work on trying to get that.”

MJ: How did you come to live in Whitsett?

RF: I was getting married that summer, after M.F.A., so I wanted to be close to UNCG. We looked all over Greensboro. One day the Realtor said, “I found a place out in Whitsett.” It was an old two-story house, and I said, “Wow, this is great. It gives me all the room in the world, studio room all over the place.” Whitsett, at the turn of the century, was an institute, a prep-type school. It was called Whitsett Institute. A lot of these old houses were used as dorms and residences for the faculty and the students.

MJ: Tell me about being mayor. A lot of artists make political statements, but you don’t see a lot of artists as politicians.

RF: What started happening while I was in graduate school was you, started getting this movement in, from Greensboro, Burlington and Gibsonville. They didn’t care one iota about Whitsett’s history. They just wanted a jumping off point to the Interstate. That just infuriated me and my wife. We thought, “What can we do to safeguard this?” There was a county commissioner named Jackie Manzi. We were at a meeting, and she said, “What you guys ought to do is incorporate.” So I said, “Hmm.” We got a bunch of people together and started talking about incorporation to protect us from all of these other people trying to take a bite out of us. That’s the reason I got involved, was to protect the area and the landscapes that I really loved . . . We incorporated back in the early ’90s. They wanted me to be mayor to begin with. I said no, I’m not going to be a mayor, but I’ll be a council member. I’m an artist. I’m not a politician. So that was good for a while, but about 12 years ago, I became mayor because I felt like there was a need at the time.

MJ: Does it ever feel weird being an artist and a mayor? Do you have to campaign?

RF: No, I don’t. It’s two different hats. It’s totally different. You take one hat off and put the other one on

MJ: You’ve been creating art for a long time. Is there ever a temptation to think there’s nothing new in art, nothing new in your art?

RF: This is what you have to understand — in art, you try to keep growing all through your life. I’m not going to switch over to something totally different. I feel like I still have a lot to learn. I’m still making discoveries. It still seems fresh to me. Whether it feels fresh to somebody else doesn’t matter. I don’t want to get off on some tangent that makes no sense whatsoever. I’m still trying to understand what the hell I’m doing! [He laughs.] Really, it’s true. It’s so elusive. I just got through doing three portraits. They were really nice. Each one of them had a totally different feel because each one was a totally different human being, with different things you’re trying to get. That’s exciting.

MJ: What can people learn from this exhibit, about you, that they didn’t know before?

RF: I guess you can start at the beginning and see where I’m struggling, trying to get an understanding of something, and as I progress, maybe you can see what that is. All of this was preparing me to understand how to see, how to paint. OH

Maria Johnson is a contributing editor of O.Henry.