Tapestry Of Home

Ann and Cliff Bridges weave together many threads at Wood Meadow

By Maria Johnson • Photographs by Amy Freeman

After moving to a brand-new second home, Cliff and Ann Bridges didn’t want to be those people.

You know: the people who build and move, and build and move, a three-dimensional expression of restlessness.

So they stayed put, with their three kids, in their perfectly fine custom-built home, which soon was bumping elbows with other perfectly fine custom-built homes.

They wanted breathing room, but they waited. They bought a wooded lot and sat on it. The 2-acre parcel was in Brandt Trace Farm, just outside the city limit on the north side of Greensboro, a bluebird’s flit away from Lake Brandt.

The lot had everything they wanted: space, trees and privacy afforded by a watershed in back and a fenced meadow in front.

For eight years, Cliff and Ann waited on behalf of the kids, who loved their house, their neighborhood, their friends, their schools.

They waited until 1986, when their youngest child was a senior in high school.

Then they built and moved again.

This time, it was for keeps — or as long as humans can keep anything.

This time, it was Wood Meadow, the setting in which Cliff and Ann — both former employees of Burlington Industries — would braid the strands of their well-traveled lives.

He didn’t believe in dating co-workers.

She didn’t either.

But in December 1975, the company Christmas dance was on the horizon at the Bur-Mil Club, an employees-only retreat on the edge of Lake Brandt.

Cliff wanted a date. So did Ann.

He asked. She said yes.

A few months later, he popped another question.

She said yes again.

They honeymooned in Bermuda, the lanky, beach-boyish Cliff and the sparky, petite Ann. Forty-two years later, the young couple smile, aglow, from a framed snapshot propped on a chest in their master suite.

It does not escape them that the relationship took flight around the bend of the lake where they live now.

“When this property became available we said, ‘That’s it!’ We love this area,” says Cliff.

A son of Greensboro’s Lindley Park neighborhood, Cliff grew up attending family reunions at the nearby Guilford Courthouse National Military Park. Ann came from rural Pennsylvania, hundreds of miles away, but the couple shared a reverence of nature and an abiding respect for people who make things from scratch.

“My father’s father had a cast-iron foundry,” says Cliff. “My other grandfather was logger with saw mill. Ann’s family was in the oil and gas business. We both come from families where people did hard work — oil, gas, metal, wood.”

The women in their families created with food and fabric. With that legacy, Ann and Cliff appreciate items crafted with care.

“For us, it is about how things are made and who made them,” says Cliff.

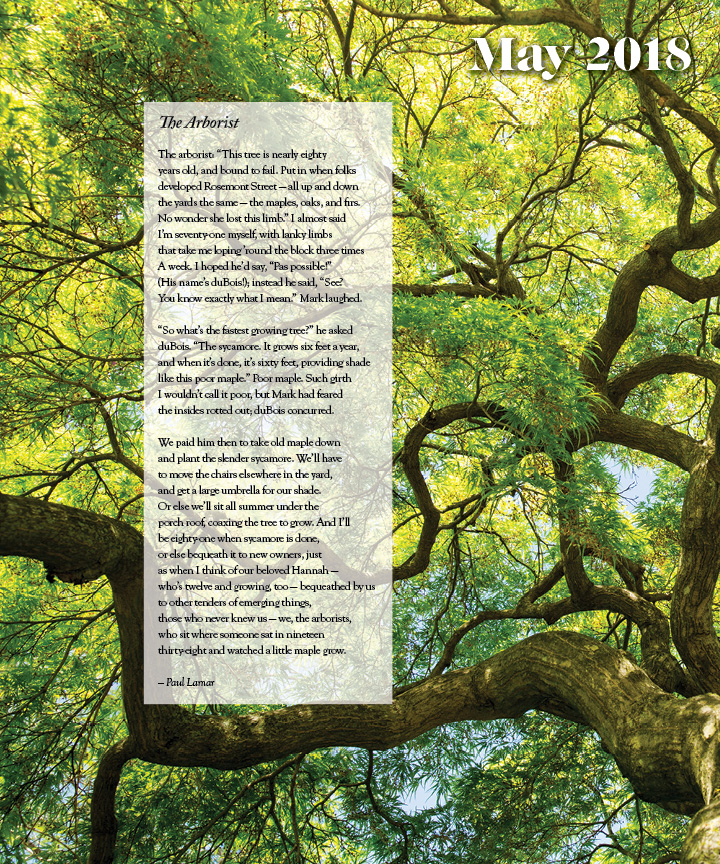

With their textile backgrounds, it’s no surprise that the couple have created a home rich in color and texture, starting with the façade.

The coarse veneer is called tabby, a concrete that’s made from sand, lime and crushed oyster shells, and is most often seen in old coastal towns.

Cliff and Ann, both shell collectors, first saw the nubby material on an anniversary trip to Sea Island, Georgia. The finish encapsulated their love of shells and coastal living.

But back in Greensboro, they had a devil of a time finding a local contractor who could do tabby. A search of the East Coast turned up an elderly gentleman and his sons in Wilmington. They were booked, but they trained a Greensboro couple to do the work. The couple used shells harvested near Topsail Beach. They applied the chunky sea mud by hurling it against the walls and waiting to see what stuck.

“They literally picked it up and threw it with their hands,” says Cliff. “It created the biggest mess. If you dig around the foundation of the house, you’ll find some of the clumps.”

The resulting pale gray topcoat — think calcified bouclé — finds elegance next to robin’s-egg-blue shutters and a bark-colored roof with dormers. The effect is soft-spoken.

The mingling of color and texture continues inside the home with a statement foyer cloaked in grass cloth. Japanese folding screens hang high, flattened on the walls. The floor is creamy marble inset with taupe diamonds. A split staircase, edged with Chinese Chippendale railing, anchors the space. Both branches of the steps land on a catwalk balcony.

It’s an excellent perch, one frequented by the couple’s two miniature Alaskan Klee Kai huskies, Tahoe and Aspen, who make the climb to survey their kingdom.

The vantage point is nice for humans, too. Face east, and you gaze out above the front door, through a Palladian window, and into a meadow bordered by white fences. The neighborhood association maintains the oasis as a common area.

Twirl 180 degrees on the catwalk, and you look through a cavernous family room, out a two-story bank of windows, and into woods that filter the golden rays of afternoon.

“We learned this, again, with our travels,” says Cliff. “When light comes into the house from the east, it wakes you up. In the evening, when you’re having sundowners, it’s nice to have light from the west on your back porch.”

Cliff and Ann designed the 6,000-square-foot home with the help of Greensboro draftsman Howard Thompson. The inside-out design began with the couple figuring out how big they wanted each room to be. Thompson jig-sawed the rooms into a plantation-style home with the essentials of retirement living on the first floor. The lot accommodated a wide footprint.

“This was definitely a unique plan,” Cliff says. “In all of our travels, I don’t know that we’ve ever seen anything like this.”

Like the grand staircase, the house is laid out in a flattened “Y”-shape. The trunk contains the foyer in front — flanked by a dining room and a sitting room — and a lodge-like living area in back.

Deep reds and greens ground the living area. Tapestries, plus a towering stone fireplace and a bronze wheel-shaped chandelier add English manor house gravitas.

The room is lightened by Audubon bird prints, more grass cloth and the wall of windows. Cliff and Ann love to sip morning coffee or an evening drink from comfortable club chairs, clad in Ralph Lauren paisley, at the base of the windows.

The home’s wings sprout from either side of the core. They contain bedrooms, his-and-her offices, a greenhouse and a kitchen at the center of the home.

Ann requested the kitchen, which has no exterior walls, so she could focus better on cooking and so that, during catered parties, the din of the kitchen could be sealed off, with sliding doors, from the main living area.

French doors link the kitchen to a Florida room with murals by Don Morgan. The curvaceous sunroom mimics the shape of a seashell; shelves display the real shells that Cliff and Ann have picked up from beaches in Florida and the Caribbean. They have bought some of the more exotic specimens.

Throughout the home, the couple have meshed pieces they’ve purchased and inherited.

Ann, who migrated to Greensboro in 1972, contributed heirlooms from her family home in Dunns Station, Pennsylvania, a couple of hours south of Pittsburgh.

After she and her first husband divorced, she went to work in the travel department of Burlington Industries, scheduling trips for executives.

A promotion vaulted her into managing the company store inside former corporate headquarters on Friendly Avenue in Greensboro. Demolished to make way for more stores at Friendly Center, the landmark Modernist building had a distinctive X-patterned steel exoskeleton.

Ann was in the store one day when Cliff, a technical director who also was recently divorced, walked in with his two children. One of Cliff’s former coworkers, who had transferred to the company store, nudged Cliff to ask Ann to the Christmas dance.

They wed in 1976 and set about knitting together their families — Ann’s son plus Cliff’s son and daughter — and their belongings.

Cliff arrived with several handcrafted pieces he’d made as a student at UNCG’s Curry School, a K-12 lab that was started on campus as a training ground for teachers. The innovative school opened in 1892 — back when the university was called the State Normal and Industrial School — and was adopted by the Greensboro city school system before closing in 1970.

As a Curry student in the late ’50s and early ’60s, Cliff got to school by riding a city bus down Walker Avenue. He loved shop class, where industrial arts teacher David Rigsby showed students how to make fine furniture. Cliff’s handiwork peppers Wood Meadow.

One piece, a mahogany Federalist-style clock with hand-turned finials, gleams in the sitting room. The space is a microcosm of the home.

The handmade clock rests on a low table; the base is an old sled with bowed wooden runners. The couple found the antique sled during a trip to Aspen.

Cloisonné plates stand on the fireplace mantel, along with Taiwanese figurines and Chinese dragons pulled from hand-blown glass.

The fireplace is bookended by two cherry nightstands, complete with brass hardware, leftover from a suite of bedroom furniture by Henkel Harris.

A clivia plant from the couple’s greenhouse flaunts pale orange flowers nearby.

The rug underfoot is a plush hand-cut Chinese number in cream, taupe and brown.

The custom-made armchairs and love seats appeared early in the marriage. For Wood Meadow, they were refreshed with cocoa velvet stitched with a cream botanical design.

A carved camphor chest, found by designer Terry Lowdermilk, supports a table at the center of the room.

An orange and purple canvas by Danish modern artist Hans Petersen splashes energy across one wall. Throughout the home, art hatched elsewhere hangs beside the work of local artists including Nancy Bulluck, Kathryn Troxler, Judy Lomax, Sandy Pittman, Barbara Glover and Bill Mangum.

Per the home’s plantation style, every room on the ground floor has at least one door leading to the outside, easing the flow of breezes and people.

“We just wanted everything to flow out, onto the earth,” says Ann.

Garden designer Chip Callaway dressed the home in glossy green Schip laurels and magnolias accented by peeling-bark birches and pings of seasonal color from dogwoods, redbuds, hellebores and lusty choirs of daffodils. Stonemason Milton Dillingham cobbled together the flagstone porches that ring the house. Cliff and Ann moved into Wood Meadow in January 1987, a day before a heavy snowfall hushed the city.

“We lost power,” says Ann, who remembers that the construction dumpster and a portable toilet were blanketed in white, too.

She and Cliff laugh at the story.

Now.

For the last 30 years, Wood Meadow has been the couple’s base of operation through career and life changes.

After becoming a buyer for Burlington’s 60-some company stores and traveling on the same jets she used to book for brass, Ann left the organization a few years before they moved into Wood Meadow.

She started Little Women, a chain of boutiques for petite women, in 1984. She operated locations Greensboro, Winston-Salem and Raleigh.

Cliff left Burlington in 1987, the same year they moved into Wood Meadow and joined Ann in running the stores.

The couple closed the stores in 1998 as the appetite for high-end clothing faded. Cliff joined another corporation, PGI, and specialized in nonwoven materials. His home office contains framed evidence: a Levi’s denim set made from virgin polyester and two Nike runner’s jerseys, made from recycled soda bottles. Runners from a half-dozen countries, including the U.S., wore similar singlets in the 2000 Summer Olympic Games in Sydney, Australia.

Cliff also helped to develop and shares a patent for a lightweight disaster-relief blanket made from polyester and polypropylene.

When PGI headquarters moved to Charlotte, Cliff and Ann bought a condo in the Dilworth neighborhood and lived there for a while. They’ve since sold the condo, and another home in Grandfather Mountain, but they never gave up Wood Meadow.

In fact, they’ve never stopped creating the homestead.

In 2014, they hired master stonemason Brian Pacheco to expand the garden with stone pathways, a koi pond, waterfalls, a bridge, a creek-side patio and fire pit. He chinked low walls and rocky pylons with ropy grapevine mortar.

Two pylons topped with stone spheres stand guard at the driveway entrance. Two more posts, which are up-lit, mark the threshold between garden and watershed. At night, the posts serve as beacons to hikers and cyclists who traverse the trails around Lake Brandt.

To top off the souped-up garden, Ann and Cliff contracted Eric Morley, co-owner of the Boone-based Carolina Timberframe and a former neighbor at Grandfather Mountain, to install a freestanding tree-house tower.

“It stands among the trees as if it were a tree,” says Cliff.

Easier on the living trees than a platform nailed into branches — and every bit as much fun for Cliff and Ann’s eight grandchildren —the 30-foot tower was constructed off-site with mortise and tenon joinery. The craftsmanship reminds Cliff of his maternal grandfather, Eli Oscar McQueen, a lumberman. Rusty-fanged saw blades, which Cliff bought at The Farmer’s Wife antiques store in downtown Greensboro, adhere to the tower in places where they pose no danger.

Eric and his crew installed the tree tower in exchange for a promotional video produced by Cliff’s company, Xedge Communications Design and Sustainability. You can see the YouTube video by searching “timber frame tree house tower.”

The latest postscript to the wooded playground is a regulation bocce court, a nod to Ann’s family’s passion for playing bocce on the beach. If you doubt that anyone would use a bocce court enough to justify the cost of building one (“I probably have a mental block on that,” Cliff says, fumbling for a figure), consider that the couple have hosted 10 bocce parties since christening the court last Labor Day.

It’s easy to get up a game, they say, because the sport allows a player to lob a ball with one hand while holding a drink in the other.

Now 30 years into Wood Meadow, at an age when most people refrain from enlarging homes and gardens, Cliff and Ann — he’s 72 and she’s 76 — continue to generate the warp and weft of memories at their sylvan refuge.

They’ll stay as long as they are able.

“This is a house for life,” says Cliff. OH