Scuppernong Bookshelf

Apropos

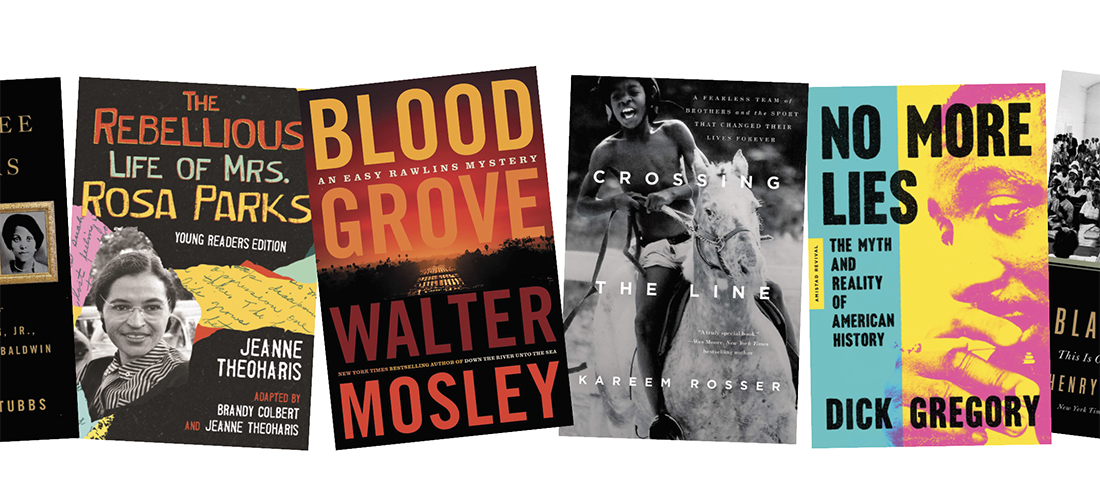

A bevy of February releases fit for any month of the year

Compiled by Brian Lampkin

A good argument can be made that when you designate a month as belonging to someone or some group (Women’s History Month, Poetry Month, etc.), you thereby diminish the importance of women’s history or poetry in the other eleven months. It’s not likely the intended effect, but perhaps it plays out that way on occasion. The better use of, say, Black History Month, is to highlight (in this case) books that will inform your reading for the entire year. And I don’t really think that the fact that we celebrate my birthday but once a year diminishes my personhood for the other 364 days. In any case, publishers recognize Black History Month and use it to put out a bevy of related books. Let’s take advantage of the largesse and talk about the best of these new releases for February.

Feb 2: The Three Mothers: How the Mothers of Martin Luther King, Jr., Malcolm X, and James Baldwin Shaped a Nation, by Anna Malaika Tubbs (Flatiron Books, $28.99). Berdis Baldwin, Alberta King and Louise Little were all born at the beginning of the 20th century and forced to contend with the prejudices of Jim Crow as Black women. These three extraordinary women passed their knowledge to their children with the hope of helping them survive in a society that would deny their humanity from the very beginning. They each taught resistance and a fundamental belief in the worth of Black people to their sons, even when these beliefs flew in the face of America’s racist practices and led to ramifications for all three families’ safety.

Feb. 2: The Rebellious Life of Mrs. Rosa Parks (Young Readers Edition), by Jeanne Theoharis (Beacon Press, $18.95). Because Rosa Parks was active for 60 years, in the North as well as the South, her story provides a broader and more accurate view of the Black freedom struggle across the 20th century. Theoharis shows young readers how the national fable of Parks and the civil rights movement — celebrated in schools during Black History Month — has warped what we know about Parks and stripped away the power and substance of the movement. This book illustrates how the movement radically sought to expose and eradicate racism in jobs, housing, schools and public services. It also highlights police brutality and the over-incarceration of Black people — and how Rosa Parks was a key player throughout. Rosa Parks placed her greatest hope in young people — in their vision, resolve and boldness to take the struggle forward. As a young adult, she discovered Black history, and it sustained her across her life. The Rebellious Life of Mrs. Rosa Parks will help do that for a new generation.

Feb. 2: Blood Grove (Easy Rawlins, 15), by Walter Mosley. Let’s not leave history to the historians! Mosley has always been a sly chronicler of Black life and history in his fiction, and this new mystery puts private detective Rawlins in the heart of the social upheaval of 1969, California. No need to have read the other 14 Easy Rawlins books — you can jump in here without missing a beat.

Feb. 9: Crossing the Line: A Fearless Team of Brothers and the Sport That Changed Their Lives Forever, by Kareem Rosser (St. Martin’s Press, $28.99). Born and raised in West Philadelphia, Kareem thought he and his siblings would always be stuck in “The Bottom,” a community and neighborhood devastated by poverty and violence. Riding their bicycles through Philly’s Fairmount Park, Kareem’s brothers discover a barn full of horses. What starts as an accidental discovery turns into a love for horseback riding that leads the Rossers to discovering their passion for polo. Pursuing the sport with determination and discipline, Kareem earns his place among the typically exclusive players in college, becoming part of the first all-Black national interscholastic polo championship team.

Feb. 16: No More Lies: The Myth and Reality of American History, by Dick Gregory (Amistad Press, $17.99). This republishing of No More Lies offers an incomparable satirist’s intellectual, conspiratorial and humorous spin on the facts. The late Dick Gregory examines numerous aspects of culture and history, from the slave trade, police brutality, the wretchedness of working-class life and labor unions to the 1968 Civil Rights Act, the Founding Fathers, “happy slaves” and entrepreneurs. No subject is off limits to his critical eye. Gregory was a comedian, civil rights activist and cultural icon who first performed in public in the 1950s. And it will come as no surprise to learn that he was on Comedy Central’s list of “100 Greatest Stand-Ups.”

Feb. 16: The Black Church: This Is Our Story, This Is Our Song, by Henry Louis Gates, Jr. (Penguin Press, $30). For the young Henry Louis Gates Jr., growing up in a small, segregated West Virginia town, the church was his family and his community’s true center of gravity. Within those walls, voices were lifted up in song to call forth the best in each other, and to comfort each other when times were at their worst. In this book — his reckoning with the meaning of the Black church in American history — Gates takes us from his own experience onto a journey across more than 400 years and spanning the entire country. At road’s end, we emerge with a new understanding of the centrality of the Black church to the American story — as a cultural and political force, as the center of resistance to slavery and White supremacy, as an unparalleled incubator of talent and as a crucible for working through the community’s most important issues. This is the companion book to the upcoming PBS series.

Public Service Announcement: In response to the ongoing COVID crisis in Guilford County, Scuppernong Books has returned to appointment-only browsing with an emphasis on curbside pickup. We continue to encourage everyone to keep the health of our friends, families and community in mind as we mask up, stay home when possible and keep social distance. With our freedom, we choose care, compassion and community well-being. OH

Brian Lampkin is one of the proprietors of Scuppernong Books