Simple Life

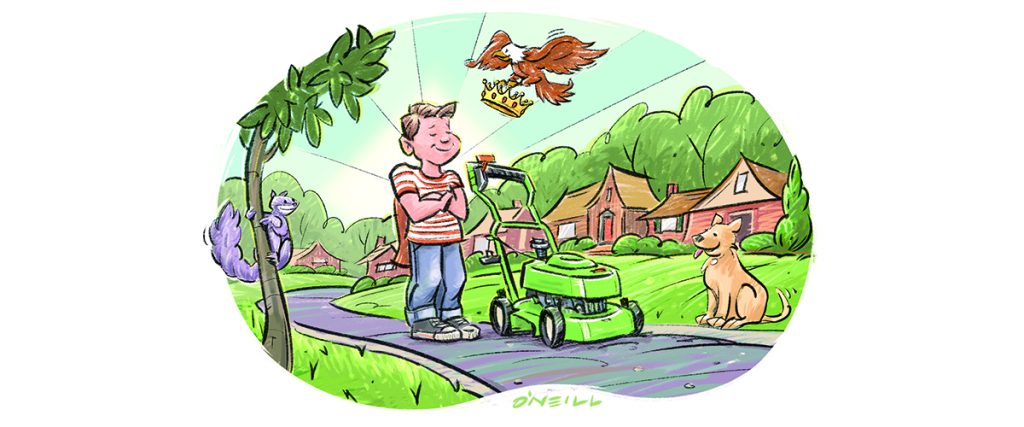

Return of Jimmy the Lawn King

Fresh-cut grass stirs up memories

By Jim Dodson

It started with a simple phone call from our neighbor across the street. Mildred Horseman had seen me mowing my family’s yard and wondered if I might be willing to mow her lawn. Her husband, Gene, was just home from the hospital and under strict doctor’s orders to rest for a month. She even offered to pay.

It was early summer, 1968, and I was 15. We were new to the old neighborhood where everybody had lush green lawns. I’d been mowing lawns since age 12, trusted not to destroy anything or chop off my own toes.

“I’ll send Jimmy right over,” said my mom. “No need to pay him. He loves mowing the grass.”

That was partly true. I liked mowing grass. I also liked money, which I needed to buy the beautiful classical guitar I had my eye on at Moore Music Company. It was $95, a whopping $800 in today’s dollars.

So off I went with our crotchety old Sears & Roebuck power mower, which normally took forever and required a number of impolite muttered oaths to start. Mr. Horseman sat on his screened porch watching me unsuccessfully crank until I had to rest my arm. He finally got up and stepped outside.

“Jimmy,” he said. “Come with me. I’ve got just what you need.”

In his garage sat a bright green Lawn-Boy power mower, one of the most beautiful things I’d ever seen.

“She’s got a few years of age on her, but will almost always start on the first pull. I keep her tuned up.”

He was right. One pull and she started. Gene Horseman went back to his club chair on the porch and I got busy on his lawn, marveling at the way his Lawn-Boy cut grass. When I finished and put his mower back in the garage, he waved me onto the porch. Mrs. Horseman had brought out lemonade.

“So what do you think?”

“Great,” I said. “Wish my dad would get one of those.”

“They’re pretty reliable,” he said. “One of the oldest brands in America, invented by a guy who built the first outboard motors for boats.”

As I drank my lemonade, I learned Gene Horseman was a retired business professor from Michigan. The Lawn-Boy mower, he explained, was created before WWII by a Wisconsin man who built Evinrude outboard engines. “I knew him when I was young. He became quite the successful businessman.”

Gene Horseman handed me a ten dollar bill. Sadly, I was compelled to explain that I was unable to take his money due to a mother who didn’t care a fig if I became a successful businessman.

“In that case,” he said, “how about we do a deal. You mow my lawn this summer and you can use the Lawn-Boy to mow lawns along the street. Sound good? I’ll even buy the gas.”

It did sound good, a potential gold mine at ten bucks a clip. But I didn’t know any of the neighbors yet.

“Print up some fliers,” he said. “Or, better yet, I’ll have Mildred get on the phone. You’ll have a job or two in no time.”

Within a week, I had two paying jobs, half a dozen regulars by the middle of summer. At ten bucks a pop, I was the richest kid on the block. By July, the Yamaha classical was mine. My mom took to calling me “Jimmy the Yard King.”

It was my first real job.

I also had my first real crush that summer on a cute girl from Luther League named Ginny Silkworth. Ginny had a great laugh and a solid right hook. When I asked her to go to the movies, she laughed and punched me sharply on the arm. We went to see Franco Zeffirelli’s Romeo and Juliet at the Cinema on Tate Street near UNCG, an evening somewhat diminished by the fact that my father had to drive us to the theater and never stopped chatting with my date.

That summer was long and hot for America, one of the most tumultuous in the nation’s history. Rev. Martin Luther King and Sen. Bobby Kennedy were both gunned down by assassins that spring, and an unpopular war in Vietnam took an even ghastlier turn. Race riots erupted in Cleveland, Miami and Chicago.

But it was also the summer that Ginny Silkworth and I went to see The Graduate, the Beatles released “Hey Jude,” and I snagged a second job teaching guitar to kids and senior citizens at Mr. Weinstein’s music store. Between mowing and teaching, my pockets overflowed. I started saving money to buy my first car.

Something about the orderliness and smell of fresh-cut grass and the satisfaction of a job well done permeated my teenage brain and grounded me in a way that made my narrow world seem oddly immune from all the bad news on TV.

It was the first and last great year of Jimmy the Yard King, though its impact was lasting.

Perhaps this explains why, when my wife and I built a post-and-beam house on a high forested hill near the coast of Maine — my first home ever — I created a large garden that featured more than half an acre of beautiful Kentucky bluegrass and fescues.

By then I’d graduated to a serious deluxe John Deere lawn tractor that gave me more than a decade of mowing bliss. A sad parting came, however, when we packed up to move home to North Carolina and discovered there was no room in the moving van for my dear old John Deere.

I seriously considered driving my Deere all the way to Carolina, but finally gave up and sold it to our snowplowing guy for a song. I still have dreams about it.

Today, back in the old neighborhood where I started, I own a modest suburban patch of grass I can mow with my Honda self-propelled mower in less than 18 minutes.

It’s a fine mower, but nothing compared to Gene Horseman’s marvelous Lawn-Boy. Professional lawn crews now roam our streets like packs of Mad Max mowers, offering to relieve me of my turf obligations for 75 bucks a pop, roughly what it once took me a full week to earn cutting grass. They seem offended by an old guy who loves to mow his own yard.

Sometimes, when I’m cutting grass, I think about that faraway summer and Ginny Silkworth, my laughing first date. We stayed in touch for four decades. Ginny became a beloved teacher in Philadelphia and passed away a few years ago. I miss her laugh, if not her punch.

Maybe the smell of fresh-cut summer grass does that. Whatever it is, if only for 18 minutes once a week, Jimmy The Yard King is back in business. OH

Jim Dodson is the founding editor of O.Henry.