Home Grown

By Cynthia Adams

On a recent trip with friends, I casually mentioned my father’s unfortunate incarceration, an expression adopted from the character Anthony Bouvier, portrayed by Meshach Taylor, on the hit sitcom Designing Women. Fans of the show may recall that from 1986–1993 Taylor played a gentle quipster, unfairly convicted of robbery.

I preferred Bouvier’s jokey euphemism; it landed gentler than saying, “My father went to the big house.” Or, “Dad did time.”

Prison talk is freighted, folks. Predictably, eyebrows raised.

“It’s not like he killed anyone,” I hastily added. What I didn’t add was he was merely one case among others in my family line.

A former mentor shared these encouraging words, “Normal families seldom produce writers.”

Take this magazine’s namesake and this city’s native son, William Sydney Porter — pen name O. Henry — who went on the lam to Honduras before serving time. He served three years in an Ohio prison; my father served only three months. I found myself bringing that up, as if it explains anything. Dad, however, could have easily walked out of an O. Henry plot — with a love for storytelling and an obsession for Pepsi-Colas and Mounds candy bars.

Dad, himself, and other relatives were never shy about sharing our family’s hapless narrative.

During a visit in Atlanta with my great uncle, Miles McClellan, he shared an alarming story. Our ancestral widowed Scots-Irish grandmother killed a tax collector during the Great Famine. “I’ve spent time at the Library of Congress,” Miles confided, “trying to learn more about her.”

Uncle Miles told an incredible tale: She whacked the tax collector with a fireplace poker when he attempted to collect their cow in lieu of taxes. She was spared a death sentence, but she and her children were exiled.

He died before finding proof, but the tale had taken unshakeable root in my imagination.

There was more. Uncle Miles himself experienced incarceration as an adventurous young man who loved newfangled motor cars. He sought his fortune in Atlanta, starting one of the city’s early car dealerships. My grandmother insisted her favorite brother was framed by older, jealous rivals. Then, the narrative grew tricky: He fled after faking his own death by driving his Model T into a creek, then lived in Baltimore under an assumed name. But he returned to face the charges, just as O. Henry did, however false. My grandmother fainted outright when her brother walked up her driveway, very much alive.

After serving time, Uncle Miles went on to found another successful business — this time selling municipal water towers — and (honestly) earned wealth. He piloted his own plane, lived in an Emerywood mansion, and remained witty and compassionate, while walking the straight and narrow.

But when my father was sentenced to a federal penitentiary in Birmingham, Alabama, tales of redemption didn’t soothe us, despite his funny and considerate probation officer, Randy Harrell, who became a family friend. The fact that Dad was appointed a pre-trial probation officer seemed a clear indication of pending doom. When Dad was led away in handcuffs, I was a new college student. Three younger siblings were still at home. Dad was jailed at Maxwell Air Force Base with Watergate offender Charles Colson. My liberal father’s response? “This is cruel and unusual punishment,” he wrote to the warden and to anyone he could think to complain to.

Dad and Charles apparently became buddies, although Dad was wary of Colson’s “jailhouse religion.” I kept a letter sent by Colson to me on Pentagon stationary urging me to keep up my studies. The logo, incidentally, is crossed out.

Dad returned to a business and family life in ruins. And the family curse continued. A young sibling would wind up spending months jailed for fishing without a license — so help me God. (He had a prior DUI). The old saw about he who represents himself in court has a fool for a client proved true in his case and mine; read on.

When appealing a driving conviction before Judge Elreta Alexander before her retirement, I tested that theory. Standing well apart from the hangdog guilty group and edging closer to the allegedly innocent, I pleaded “guilty with exonerating circumstances.” The judge snapped: “Stand there with the rest of the guilty!”

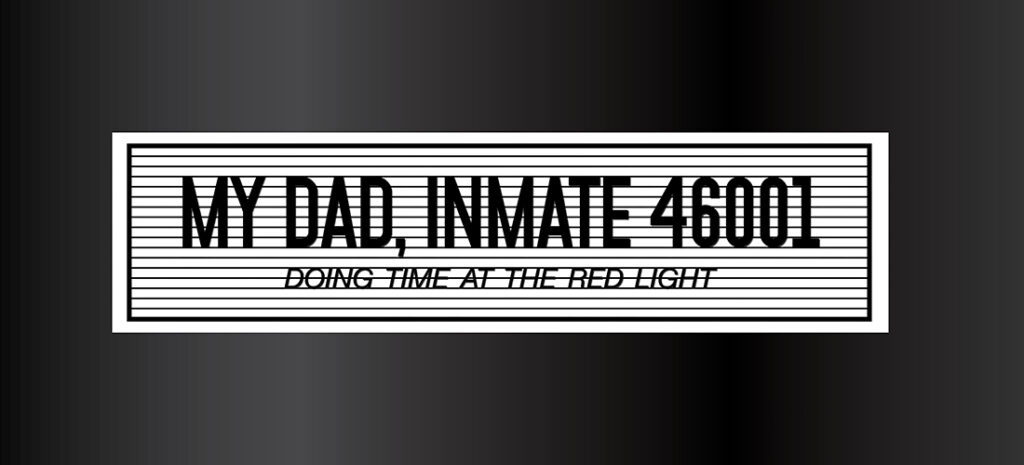

Admonished, I slipped a folder of images of “No Right on Red” signage at a downtown stoplight behind my back, now terrified of actually presenting my evidence. Would this clever judge realize my wide-angle lens might have distorted the sign’s distance from the stoplight? I had sworn to give honest testimony; but were the pictures just a tad misleading?

After systematically finding each “innocent” plaintiff guilty, Judge Alexander beckoned me to approach the bench. “You. The one who doesn’t know if she’s guilty or innocent. What is it that you brought?” she asked, demanding the ill-concealed folder.

As she studied my pictures, I lightly joked that the worst that could happen was she would find me guilty. Fixing me with an assessing look, she warned that, no, things could get worse.

“Read your ticket,” the judge said grimly. She could, in fact, jail me for illegally turning right on red. And levy fines.

Jail?! I grew redder than a fully ripe McIntosh apple.

Perhaps because the ticketing officer failed to appear, Judge Alexander relented, ruling prayer for judgment continued, a PJC.

I paid the court costs and sprinted out — a near miss as a jailbird.

Long afterward, I refused to turn right on a red light, no matter how many horns honked or fingers flipped me off.

Felonious grandmother, uncle, father and brother, know this: I vow to break the chain of unfortunate incarcerations.

That annoying driver who rubbernecks before proceeding right at the stoplight? It’s probably law-abiding little ole me. Just wave hello and please don’t honk; there’s some serious ancestral baggage riding with me and a curse I’m doing my best to shake. OH

Cynthia Adam is a contributing editor to O.Henry magazine.