O.HENRY ENDING

Obits and Pieces

The tale of a quirky hobby practically writes itself

By Cynthia Adams

Collecting clever obituaries is a hobby of mine.

It’s a far less time-consuming undertaking, erm, endeavor, than you might think.

Interesting obits are as rare as zorses (a zebra and horse hybrid). When they happen, the social media universe is alerted and the obit boomerangs around 10 jillion times. Fun, intriguing, even weird obituaries are snapshots of the strangest of hybrids: the rare, true originals who have roamed this Earth.

Douglas Legler, who died in 2015, planned his obit for the local newspaper in Fargo, N.D. “Doug died,” he wrote. Just two words guaranteed a smile and a wish that we had known him.

Yet navigating the truth about our dearly departed is a tricky thing. I know, having attempted writing tender, true or even mildly interesting obits.

Uncle Elmer’s beer can collection or lifelong passion for farm equipment may not a fascinating individual reveal, but it beats ignoring the details that made Elmer, well, Elmer. Maybe loved ones wish to eulogize a different sort than they actually knew, say, an Elmer possessing panache. Ergo, an unrecognizable Elmer.

My father, in fact, worried that his own obit might one day portray him as suddenly God-fearing, upright and flawless.

“I know some will probably show up for my funeral just to be sure I’m dead,” he’d joke, shucking off the funeral suit we nicknamed his dollar bill suit — the tired hue of well-worn money. It didn’t even complement his twinkling green eyes, which seemed especially twinkly after a funeral or wake.

Why so upbeat? “It wasn’t me,” he sheepishly confessed after the funeral of a prickly neighbor.

Bob, an older, popular colleague of mine, had a sardonic wit, too, even as personal losses mounted. Each Friday he’d drawl, “Guess me and Becky will ride down to Forbis & Dick tonight and see who died. Then we might go to Libby Hill for dinner.”

In a similarly irreverent spirit, I offered to help my father with his funeral plans in advance, jabbing at his habitual lateness. “You’ll be late for your own funeral,” I accused.

“We’ll request the hearse to circle town before the service so we’re all forced to wait the usual half hour.”

Dad rolled his eyes.

He died suddenly at age 61. Much later, I wished we had mentioned in his obituary how his end was almost as he’d hoped: in the arms of a beautiful woman.

True, his newest paramour had arms. They may, in fact, have been her best attribute. (My siblings never let me near his obituary.)

To our surprise, Preacher Lanier wanted to speak at Dad’s funeral. But Dad was not a churchgoer, we said delicately; the service would be at the funeral home. Then he revealed that they were old friends, breakfasting together each Wednesday.

Carefully, I asked that he not proselytize — as he was often inclined. He knew our father far too well to do that, he chuckled.

True to his word and a shock to me, the preacher revealed that our father underwrote the church’s new well.

Disappointingly, there would be no tour of town before the service either; the hearse wasn’t involved until we drove to the interment.

For once, therefore, Dad was exactly on time.

Like funerals, obits offer the chance to surprise us in a good way.

Lately, my friend Bill got me thinking about mine. Given my inglorious beginnings in Hell’s Half Acre, he knew exactly what he’d say at my end.

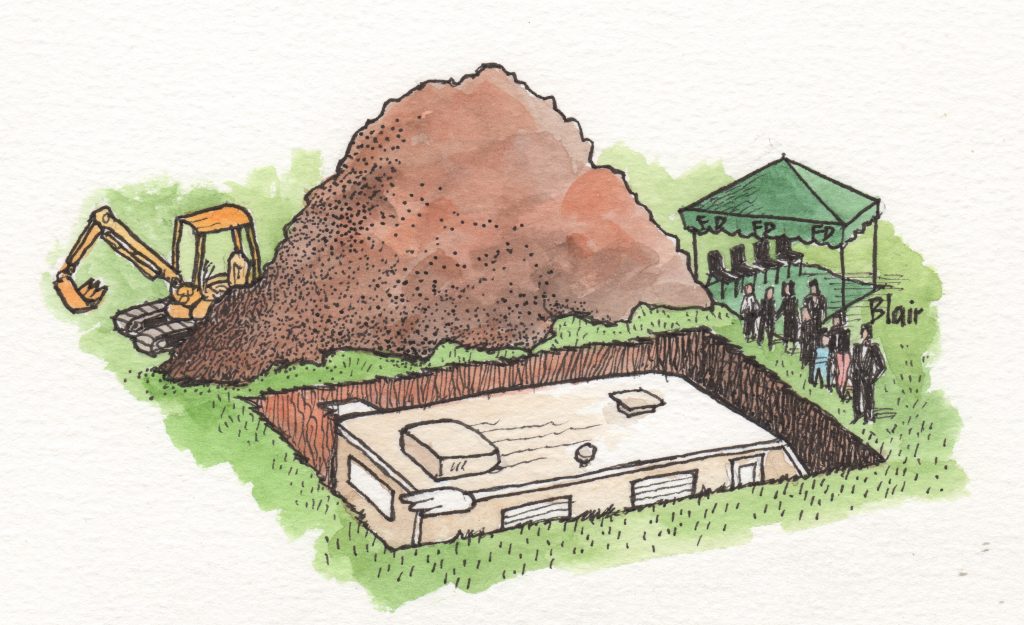

“I’d say I’d have you buried in a trailer, but it would cost too much to dig the hole,” he quipped, mocking my uncultured life.

I would never admit it to him, but that was pure genius; it ought to at least be mentioned in my obit.