Chang and Eng

Legendary twins who called North Carolina home

By D. G. Martin

If I asked you to name our state’s best-known citizen, living or dead, who comes to mind?

What if I said to think of people of who lived in Mount Airy?

I bet you would say Andy Griffith. After all, his still-popular TV show was set in Mayberry, which was based on his hometown, Mount Airy.

But long before Griffith was born, long before television, two world-famous men moved to Surry County farms near Mount Airy.

They were known in America and Europe as Chang and Eng, the Siamese Twins. Still today, almost 145 years after their deaths, people all over the world know about the two brothers, joined together from their birth in Siam (now Thailand) in 1811 until their deaths near Mount Airy in 1874.

In 1978, Irving Wallace and his daughter, Amy Wallace, wrote a popular biography titled The Two: The Story of the Original Siamese Twins. The Wallaces used their great storytelling gifts to entertain readers while laying out the details of the twins’ amazing lives. After growing up in Siam, Chang and Eng came to the U.S. and were displayed throughout the country and Europe before settling in North Carolina, marrying sisters, and having more than 20 children between them. (See attached chronology.) Until recently, The Two had a virtual monopoly on the story, but two new books provide additional facts and a more modern examination of the twins’ lives and times.

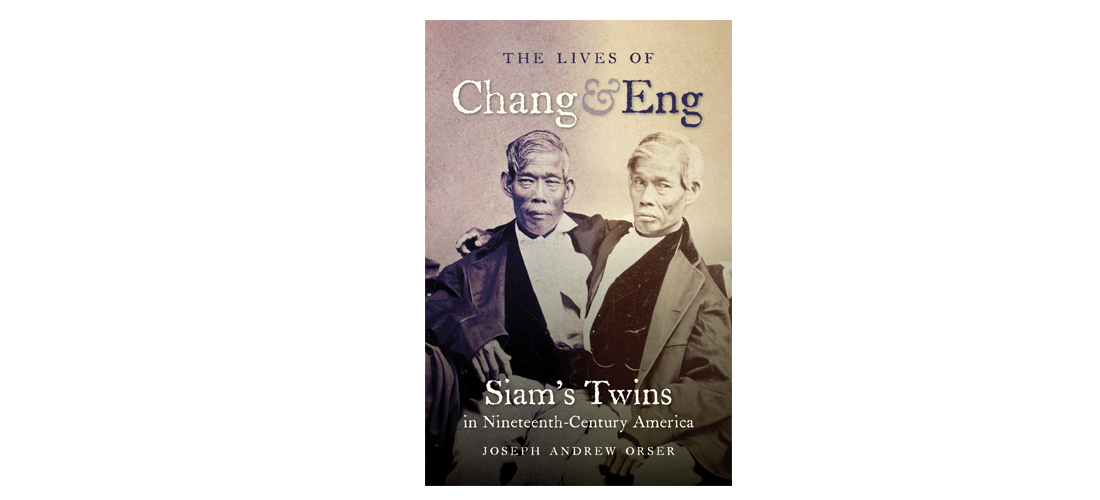

The newer books are Joseph Andrew Orser’s The Lives of Chang and Eng: Siam’s Twins in Nineteenth-Century America, published in 2014 by UNC Press, and Yunte Huang’s Inseparable: The Original Siamese Twins and Their Rendezvous with American History, published earlier this year by Liveright.

Though the Wallaces covered the story in great detail, they wrote for Americans of the 1970s. Our attitudes about race, immigration and the exploitation of unusual human specimens have evolved. Orser’s Chang and Eng re-examines the basic facts of the twins’ lives and challenges earlier understandings of the meaning and lessons of their experience. Using the reactions of 19th century Americans and Europeans to the twins, Chang and Eng is more than a standard biography. It becomes an examination and evaluation of social attitudes about race, ethnicity, slavery, immigration, citizenship, and the exploitation of the unusual and deformed.

Orser recounts a host of interesting facts about the twins that his readers might have forgotten or never knew. For instance, the twins, though born in Siam, were really of Chinese origin. Their father was certainly Chinese, and their mother may have been partially Chinese. So why weren’t they, and all other conjoined twins who came afterward, called Chinese Twins? It seems to have been a matter of 19th century branding. The explanation given by one of their managers, James W. Hale, was that they were “more likely to attract attention than by calling them Chinese.”

After traveling all over the U.S. and Europe, why settle in rural North Carolina? Their 1839 decision was, Orser writes, “well orchestrated: it was not spur of the moment.” In the big cities, he explains, the twins “were too closely linked to their public exhibition and their foreign origins; there was little room in the North for them to settle down to lives of quiet respectability.”

After moving first to Wilkes County and later into adjoining but separate farms in Surry County, they became U.S. citizens, acquired and managed slaves, and when the Civil War broke out, they supported the South, each of them supplying a son to serve in the Confederate Army.

The twins were joined at their chests by a relatively short band of tissue. Today a surgeon could separate them but the doctors of the time were uncertain. There could have been other reasons, as well. As one of their doctors explained, “Those boys will fetch a vast deal more money while they are together than when they are separate.” After their deaths, when the bodies were examined, some doctors concluded that one or both of the twins would not have survived an attempted separation.

In Huang’s Inseparable, the author’s personal background lends a special perspective. Like Chang and Eng, he grew up in Asia. After college at Peking University, he came to the U.S. and worked in the restaurant business in Alabama before completing his Ph.D. in poetics at SUNY-Buffalo. Living in the American South, he experienced challenges not unlike those that confronted Chang and Eng more than 150 years earlier. He sees the twins as fellow immigrants.

While taking Americans to task for their “ugly rhetoric against immigrants,” Huang wrote recently in The Wall Street Journal, “Throughout American history, almost all immigrants, legal or illegal, have indeed had mountains to climb . . . But few newcomers to the U.S. have crossed more daunting barriers than Chang and Eng Bunker.”

Huang uses the twins’ lives to examine other features of American society during their lifetimes. He includes a long section describing the acrimonious relations between the twins and P.T. Barnum, the clever exhibitor of rare spectacles and weirder attractions who took advantage of Chang and Eng and the public. Huang writes that Barnum understood that the American nature was to submit to clever humbug, even when it flaunted the facts.

Huang compares Barnum to a “trickster” who is an engaging confidence man and a colorful figure ubiquitous in literature and film. He dupes others and often dupes himself as well. The trickster does not know either good or evil. He is more amoral than immoral. He is a simple confidence man.

Huang argues that in Barnum’s time, “democracy also became a game of confidence, in the double sense of the word: political representatives gain the trust of the common men and pull a con on them.”

“In nineteenth-century America,” Huang continues, “no one did it better than P. T. Barnum in turning confidence into entertainment; no one was a better trickster than the Prince of Humbugs.”

To become an expert on Chang and Eng, ideally you would want to tackle all three books, but if you can only read one, Fred Kiger, Chapel Hill’s inspirational Civil War and local history speaker, suggested in a recent lecture that you start with the Wallaces’ old standard, The Two, to get the big picture. Then you will want to read the two new books for the rich, more modern perspectives they could bring to your reading table.

Chang and Eng Chronology

May 11, 1811 Conjoined twins are born in a small fishing village in Siam (now Thailand). They are named In and Chun, which became Eng and Chang. Father is Chinese. Mother probably half-Chinese.

1824 Robert Hunter, a Scottish merchant in Siam, sees twins swimming, thinks of them as monsters with potential to attract paying customers in the U.S. and Europe, but is unable to persuade the king to allow their departure from the country.

1829 With the help of sea captain Abel Coffin, the king is persuaded to allow the twins to leave. Coffin and Hunter form a partnership and enter into an agreement with the twins’ mother to pay her $500 and to return the twins within five years.

1829 Arrive in Boston, where they are displayed to crowds. Appear in New York City and other places.

1830 Travel to England in steerage while Coffin and his wife travel in first class.

January 1831 Depart England and return to U.S. (not in steerage this time) in March and resume heavy travel and exhibition schedule.

July 1831 On vacation in Lynnfield, Mass., they are accosted by locals (including Col. Elbridge Gerry, named after the Mass. Governor who gave the Gerrymandering its name). Twins are charged with disturbing the peace and required to pay $200 bond.

May 1832 Upon reaching 21 years, the twins declare their independence from the Coffin and take charge of their exhibition program.

1835-36 Exhibition of twins in Europe.

1839 The twins retire to Wilkes County, North Carolina, purchase a 150-acre farm in nearby Traphill, build a house, and open a general store.

1843 They become American citizens, adopt the last name Bunker, and marry local sisters. Chang wed Adelaide Yates (1823–1917), while Eng married her sister, Sarah Anne (1822–1892).

1844 Ten months later, each couple has a baby girl, beginning families with a total of more than 20 children.

1846 They move to nearby Surry County, where they build two houses about a mile apart on adjoining tracts of land. The families of each twin stay at their respective houses, while Eng and Chang take turns visiting every three days. They follow this pattern for the rest of their lives.

1849 The twins return to New York to exhibit with 5-year-old daughters, Katherine and Josephine, and find difficult competition from P.T. Barnum and his collection of exhibits such as the popular Tom Thumb. Unsuccessful, they return to N.C. after six weeks.

1853-54 Traveling with Eng’s daughter Kate and Chang’s son Christopher, their tour makes 130 stops and covers 4,700 miles.

1860 They agree to be displayed by the hated P.T. Barnum for the “insulting amount “ of $100 a week.

November 1860 Travel to California via rail crossing in Panama. After exhibiting in San Francisco and Sacramento, they depart California on Feb. 11, 1861.

1861-65 As owners of more than 30 slaves, they support the Confederacy. Two sons who serve in Confederate Army are wounded and captured. The loss of slaves and the value of Confederate assets creates a financial emergency.

Dec. 5, 1868 Under an arrangement with Barnum, twins depart for Great Britain with Kate and Chang’s daughter Nannie.

1869 Mark Twain writes a humorous story inspired by the twins, “The Personal Habits of the Siamese Twins.”

1870 On the Cunard steamer Palmyra returning from England, Chang suffers a stroke. His health declines over the next four years.

Jan. 17, 1874 At age 62, Chang dies, and within hours Eng follows. OH

D.G. Martin hosts North Carolina Bookwatch, which airs Sundays at noon and Thursdays at 5 p.m. on UNC-TV.