Weekend Away

Georgia on Our Minds

The Madcap Cottage gents scamper off to Savannah

By Jason Oliver Nixon

I hadn’t been to Savannah in years, and John had never visited.

Pre-pandemic, Savannah was often bandied about as a possible Madcap weekend away destination, but somehow we always wound up in places like London or, closer to home, Charleston instead. And we do love Charleston, but sometimes the Holy City can be a tad too polished.

“Savannah is like Charleston’s wild child,” noted a friend with deep ties to the Georgia coast. “We aren’t as uptight and formal, and we really like to kick up our heels and throw a good party. After all, our nickname is the ‘Hostess City.’ And remember that we are an open-container city, so always get your cocktail to go!”

Meanwhile, our next-door neighbors in High Point spend most of their time in Savannah, where they have a second home and run a ghost tour company, Savannah History & Haunts. The pair has been urging us to visit for years.

“You will love it,” said Bridgette, one half of the powerhouse behind the couple’s multi-city tour company. “There are great hotels and restaurants, and the history is off the charts. Plus, you can take one of our tours!”

John and I re-read Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil and, yes, screened Forrest Gump late one night to get into a Savannah state of mind.

Weekend away, here we come!

We decided to take George, our pound-rescue Boston terrier, along for the adventure and left the pug posse back home in the capable hands of the dog sitter.

For the five-hour drive from the Triad, John and I meandered through Cheraw and Florence, S.C., instead of facing — or more like being smoked by — Charlotte’s notorious speed demons. Still, after a few hours on the I-95 leg, John and I were ready for a strong libation as we pulled up at our weekend roost: the recently opened and absolutely stunning, dog-friendly Drayton Hotel.

Photos by Dylan Wilson

www.dylanwilsonphotography.com

George trotted in like he owned the place, and we all settled into The Drayton’s colorful Living Room, aka the lobby, where masterfully crafted, medicinal martinis were quickly rustled up. George perched happily atop a poof and preened.

Housed within the historic American Trust and Bank, The Drayton calls to mind an intimate, London-style hotel that mixes colors and patterns, giving a nod to the past with modern flourishes and understated — but beautifully presented — service. Smack on the corner of busy East Bay and Drayton streets, The Drayton offers the perfect location but feels worlds away from nearby River Street with its tourist hustle-bustle. The five-story hostelry boasts a terrific restaurant, St. Neo’s Brasserie, a chic, high-ceilinged dining room and first-rate service (our server, Libbie, was a gem). The rooftop bar wasn’t open for the season, but there is a slick, tucked-away bar in the basement and a coffee outpost just off the lobby that didn’t disappoint. Our intimate suite was equally cool with knockout views of the container ships plying the Savannah River (Savannah is the third largest container port in the nation) and a truly inspired bathroom with a wet room that paired a shower and clawfoot soaking tub.

With refreshed to-go cocktails in hand and George happily tucked away, we decided it was time to hit the town.

Savannah is the perfect walking city. Of course, the city celebrates its 22 signature squares, verdant and dripping with Spanish moss, which span one square-mile of its downtown. You will probably pick a favorite over the course of your visit. For us, it was Lafayette, but be sure to visit Chippewa, the site of Forrest’s iconic bench (his actual bench was a prop, now found at the Savannah History Museum). The squares are surrounded by historic residences with gated gardens, many of which you can tour, including the Davenport House and the Mercer-Williams home, site of the murder detailed in Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil. There’s also dreamy Forsyth Park and museums aplenty.

“SCAD seems to be gobbling up the city,” noted John as we found our Savannah sea legs and looked around for more gin to accompany lonely olives. SCAD, of course, refers to the Savannah College of Art and Design, and the institution does, indeed, seem to have kudzued here, there and everywhere in between.

We passed the famed Olde Pink House eatery (too crowded!) and questioned whether we had to wear masks outdoors — you’re supposed to.

Geographically and pandemically situated, John and I decided to follow our friend’s lead, and we truly kicked up our slip-on Converse-clad heels.

We dined at The Fat Radish (bliss!), the farm-to-table Cha Bella, The Collins Quarter and The Fitzroy. We sipped cocktails on the roof of the glamorous Perry Lane Hotel and brunched at Clary’s Cafe, the Little Duck Diner and B. Matthews Eatery. And then, we shopped.

Savannah boasts a glorious assortment of design outposts such as Courtland & Co., PW Short General Store (incredible!), Alex Raskin Antiques (the crumbling building alone is worth the visit) and minimalist favorite Asher + Rye (too Scandi spare for Madcap maximalists!). We were in home design heaven.

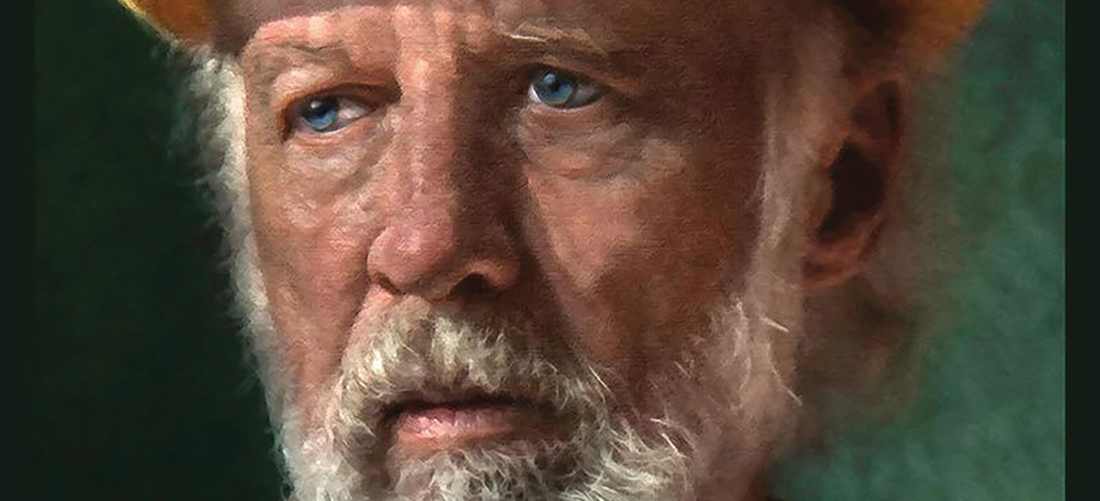

Our neighbors’ 90-minute 9 p.m. candlelit ghost tour was an especial highlight of the weekend. Throughout, we explored dark byways and atmospheric squares and learned about the ghosts and cemeteries that haunt and dot Savannah. Dan, our High Point neighbor, guided the tour. Decked in historic-styled garb, he was a font of knowledge paired with heaps of charisma and a true spirit of fun.

John and I trotted George out for long walks (Savannah is super dog friendly), sampled ice cream at fabled Leopold’s, sipped more potent potables at Artillery and the Lone Wolf Lounge, nibbled treats from Byrd Cookie Company and explored the refurbished Plant Riverside District with its power-station-meets-pure-glitz JW Marriott Hotel and river-facing sushi and biergarten eateries.

And, whew, there went the weekend . . .

But there is so much more to see and experience in Savannah. We will most certainly be back — with cool Chatham Artillery Punch cocktails in hand, of course. OH

For more information about The Drayton Hotel, visit thedraytonhotel.com.

The Madcap Cottage gents, John Loecke and Jason Oliver Nixon, embrace the new reality of COVID-friendly travel — heaps of road trips.