Wandering Billy

Dog’s Best Friend

Jessica Mashburn’s Furr Frame pinups find animals fur-ever homes

By Billy Eye

“No one appreciates the very special genius of your conversation as the dog does.” – Christopher Morley

For the last decade, Jessica Mashburn and her world-renowned partner in rhyme, Evan Olson, have been performing Wednesday evenings at Print Works Bistro. When she’s not on stage belting out the Great American Songbook, Jessica’s passion is rescuing and finding homes for stray animals.

A volunteer at the Guilford County Animal Shelter, she launched The Guilford County Furr Frames Project in 2019, digital picture frames found on the front counters of businesses all around the county with a rotating array of portraits spotlighting shelter pets up for adoption. By year’s end, over 200 dogs and cats were safely nestled in their fur-ever homes. Here are some of their success stories . . .

Bandit

Bandit is a disarmingly adorable bulldog mixed with mastiff. “Pitt-mixed mutts are the majority of the breeds found at the shelter,” Mashburn says. “There’s a stigma about the breed and, I’ll admit, when I first thought about volunteering, I had a little bit of apprehension about that,” she says. “Eventually, they’ve become my favorite breed. I find them more emotionally similar to humans in that they develop their personalities based on how they’re treated, and so do we.”

When Bandit’s family began having kids, they penned him up outside. “He got really jealous and upset and broke out of his yard one day. Another dog attacked him and the owner of that dog hit Bandit over the head with a tire iron and hurt him really badly,” Mashburn recalls. Not wanting to bring Bandit into the house, “The family surrendered him to the shelter. It was really hard on him so I immediately decided I would advocate for him. I got him involved with an amazing rescue group, Underhound Railroad, now Bandit is living with a teacher in Georgia and doing really, really well. I actually drove him down there.”

Beauford

Beauford, a Staffordshire terrier stray, was never an aggressive pooch but physically very strong. Any time someone wants to adopt a shelter pet, they are paired up in a fenced-in yard to determine if the chemistry is there. “There were a lot of people who would take Beauford out in the yard,” Mashburn explains. Larger than he looks in the photo, “It would be a bit of a tough walk because he was so strong on the leash.” But Beauford’s story has a happy ending: “He ended up being adopted,” Mashburn tells me, adding that she once spotted him at the Petco with the family that he happily adopted.

Cinnamon

A Staffordshire/Labrador mix, Cinnamon was surrendered when she was about a year old. “A lot of times,” Mashburn allows, “people want a puppy but surrender them to the shelter whenever that puppy makes the mistake of becoming a dog.” In Cinnamon’s case, her family hadn’t anticipated how much time and energy it takes to be a proper canine companion. “Her spirits were very low, she was clinically depressed and would just lie on the floor,” the singer remembers. “I actually had to carry her outside in my arms. She didn’t want to walk.” Cinnamon’s journey forward was fraught with loneliness and ill health. “She got really sick at the shelter with a respiratory infection which is very common in confined quarters,” Mashburn tells me. By chance a woman who had worked for 20 years for the school system saw a picture of Cinnamon on one of the Furr Frames. “She had a dog that looked almost exactly like her and reached out to me about fostering Cinnamon. She absolutely fell in love, adopted her and I’ve gone to visit them a few times. Cinnamon is definitely in her forever home.”

Penny

Most likely a Staffordshire terrier mixed with shepherd, Penny possesses those plaintive puppy dog eyes girls looked for in a high school sweetheart. She remained at the shelter for a long time. “Penny needed to be like an ‘only child’ with no other dogs around,” Mashburn says. “She was not aggressive to humans, she just felt threatened by other animals.” Taken in by a young person living in a small apartment, “She ended up back at the shelter but was adopted again and now has a good home. She hasn’t been back to the shelter so that’s a good thing.” Mashburn suggests people who normally only adopt golden retrievers or Labradoodles should reconsider getting a pit breed dog, “because they’re missing out on a really beautiful connection with an animal.”

Sir Diesel

Sir Diesel was found roaming around extremely emaciated, basically starving. “It took the medical team a while to get him to a place where he could be on the adoption floor. He’s a very large dog, a Great Dane/boxer mix or some variation,” she notes. “He felt very threatened by other dogs. He ended up getting rescued by Tails of the Unwanted; they put him through a great training program to help him get over his fear of other dogs eating his food. He was also very wary of certain males, it may have been because of some sort of abuse he suffered.” Eventually but Sir Diesel was adopted by a North Carolina Highway Patrolman and his wife. “He’s living the good life now with a dog brother named Hercules who was adopted through our shelter.”

Jessica Mashburn doesn’t limit her rescue efforts to our canine friends. “There are feral cat colonies all over Greensboro,” she tells me. “If there’s a shopping center with a wooded area behind it, you can bet there are stray cats living there.” On a recent excursion in search of someone’s lost kitty, she says “I discovered a feral community, about 20 of them, all spayed and neutered by local organizations. They live peacefully on some property owned by Guilford County Schools. They’ve been fed for the last 10 years by a woman who doesn’t speak English but, when I met her, there was an immediate feeling of universal compassion. Even though we don’t speak the same language, we were both touched by the survival and spirit of these cats in that same way,” she says, pausing. “I think it’s great that, within the city of Greensboro, there is a great deal of cooperation for existing feral colonies. These cats, who are not domesticated but would never hurt anyone or aggressively bite a human being, just want to be left alone to live out their lives in the environment they were born into.”

If you’re thinking of bringing a pet into your life this year, Jessica’s advice is, if you can afford it, consider adoption first. There are so many incredible companions that are waiting here at the shelter, or maybe that stray in your neighborhood, wishing with all their might to be taken into a loving home.” OH

Billy Eye ain’t nothin’ but a hound dog but I’d be lyin’ if I said he was cryin’ all the time.

Scuppernong Bookshelf

Book Orders Out of Chaos

Reading as an antidote to the roots of division

Compiled by Brian Lampkin

It’s impossible to keep up with the rapidly changing events in America at the moment. Our attention shifts from pandemic to police violence to the specter of constitutional degradation as each “breaking news” interruption determines. As I write this in June, we might find that July has mercifully brought us an alien invasion to make all matters obsolete. Nevertheless, we’ll focus on the most pressing issue of our moment.

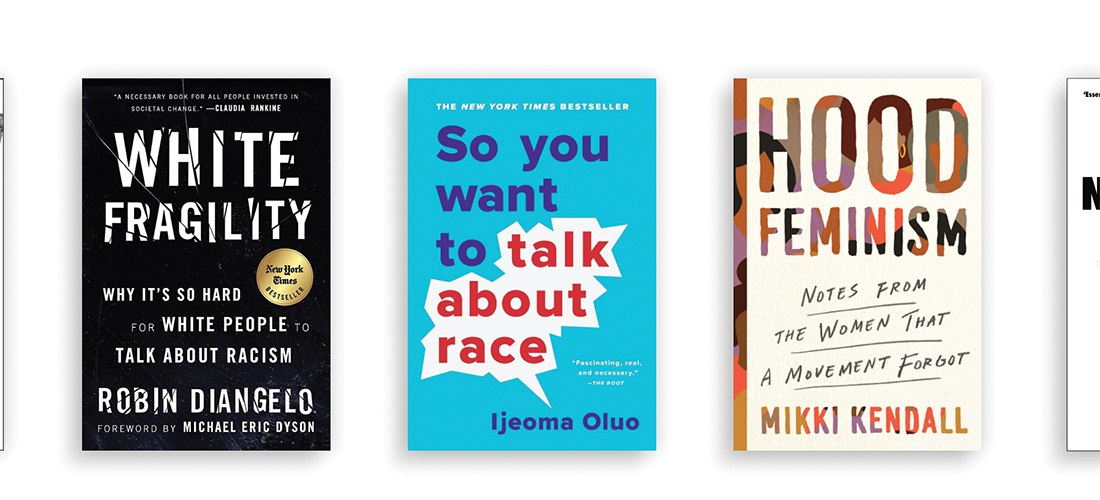

Here at Scuppernong, as in all independent bookstores across the country, we have seen an explosion in the ordering of books on racism in America. We all hope that reading will translate into meaningful change (and let’s remember that we protest to create change — protest remains an act of hope as well as resistance). The following books have been the most in demand as we face the consequences of 400 years of racial madness.

How to Be an Antiracist, by Ibram X. Kendi (One World, $27). The National Book Award-winning author of Stamped from the Beginning offers a bracingly original approach to understanding and uprooting racism and inequality in society — and in ourselves.

White Fragility: Why It’s So Hard for White People to Talk About Racism, by Robin DiAngelo (Beacon Press, $16). Explores counterproductive reactions white people have when discussing racism that serve to protect their positions and maintain racial inequality.

So You Want to Talk About Race, by Ijeoma Oluo (Seal Press, $16.99). Oluo guides readers of all races through subjects ranging from intersectionality and affirmative action to “model minorities” in an attempt to make the seemingly impossible possible: honest conversations about race and racism, and how they infect almost every aspect of American life.

Hood Feminism: Notes from the Women That a Movement Forgot, by Mikki Kendall (Viking, $26). Mainstream feminists rarely talk about meeting basic needs as a feminist issue, argues Mikki Kendall, but food insecurity, access to quality education, safe neighborhoods, a living wage, and medical care are all feminist issues. All too often, however, the focus is not on basic survival for the many, but on increasing privilege for the few.

Why I’m No Longer Talking to White People About Race, by Reni Eddo-Lodge (Bloomsbury, $18). Exploring issues from eradicated black history to the inextricable link between class and race, Reni Eddo-Lodge has written a searing, illuminating, absolutely necessary examination of what it is to be a person of color.

My Grandmother’s Hands: Racialized Trauma and the Pathway to Mending Our Hearts and Bodies, by Resmaa Menakem (Central Recovery, $17.95). Racism and trauma are addressed as the author examines white supremacy in America from the perspective of body-centered psychology. OH

Brian Lampkin is one of the proprietors of Scuppernong Books.

Short Stories

The Astrological Scuttlebutt

for Ragged Claws

Dip a toe in the water, grab the Old Bay Seasoning and dance by the light of the silvery moon now that it’s Joo-ly and reign of the crab is in full swing. Those born under the sign of home and hearth exude Mama energy . . . and as we all know, if Mama ain’t happy, nobody’s happy. (Think: Princess Diana.) Ruled by la Luna, shifting moods from laughter to tears and back again are part and parcel of Cancerians’ makeup, even more so thanks to Mercury retrograde and a series of recent eclipses. June 5’s whammy at the full moon in Sadge hit your sign in the sixth house of work and health; as July kicks off, you might be out of a job like so many in the age of ’rona, or trying to reschedule doctor visits. But the seesaw tipped in your favor on June 21 at the solar eclipse in your very own sign, sending good vibes to help you grab the brass ring. Maybe a new dream job is on the horizon? This month you’ll have to work hard to make it happen, but not before some 4th of July fireworks from yet another eclipse in your opposite sign, Capricorn, which presides over career and public prestige. Additionally all partnerships — bedroom and boardroom — are emphasized. Maybe you’ll say “Buh-bye” to a toxic vampire or dare to pair with someone new. You’ll be glad you did, Little Crab, especially when Venus sashays into your sign next month . . . about the time summer goes from steamy to sizzlin’.

Once Upon a Time

If we’ve learned anything from this era of isolation, it’s the human imagination not merely thrives but soars. Case in point: the Children’s Summer Reading Program at High Point Library. No, groups of kiddoes can’t gather, but they can still learn about cooking, gardening, origami, and creepy crawly things, perform concerts — all virtually — and of course, read. They can register in the library’s parking lot (901 North Main Street), where a mobile will be ready to hand out reading logs and prizes. Those who reach their reading goals will be eligible for a drawing on August 3 for top prizes of two bikes and a laptop. For more info, call (336) 883-3668 or highpointnc.gov.

Barre None

Should you stay or should you go? Well, if you want to learn some dance steps, you can have it either way: By learning them virtually, and presuming the planets align, in a real, live, bricks-and-mortar dance studio! (After months of virtual reality, we don’t blame you for asking, “Whazzat?”) Greensboro Ballet is, for the time being, offering dance camps for little ones in ballet, jazz, tap, hip hop, as well as hourly adult classes online and — fingers crossed — in its studio (200 North Davie Street). Hard to gauge at press time, but call the ballet company at (336) 333-7480 or go to greensboroballet.org for more information and registration.

Wedge Issue

Before the world was stricken with corona craziness, American artisanal cheese was having a moment. Consider: Last October, Oregon’s Rogue Creamery was named champion of the World Cheese Awards in Bergamo, Italy, for its blue cheese made with cow’s milk — one of 3,000-some entries from 42 countries. But the age of lockdowns and shuttered restaurants has been tough on artisanal cheesemakers. We’re fortunate enough here in the Triad that Greensboro Farmers Curb Market, Piedmont Triad Farmers Market and Salem Cobblestone Market satisfy our cravings for Goat Lady Dairy chèvres and hard cheeses from Germanton’s Buffalo Creek Farm and Creamery, among vendors. Please, be a gouda citizen and continue to patronize them — but what about small cheesemaking outfits farther afield? Answer: Victory Cheese! Yes, just as average folks are reviving victory gardens, a grassroots group of fromage-friendly enthusiasts is selling Victory Cheese Boxes. Most of the cheeses come from farms in California, Colorado, Illinois and the Northeast, but hey! What better way to see the USA than in a . . . chèvre-let? Make it a feta-ccompli by ordering a box at victorycheese.com.

Ogi Sez

Finally, there may be a glimmer of light at the end of the pandemic tunnel. So here’s hoping that July marks the beginning of the beginning. This month we may actually be able to experience live music in front of a live audience. Barring a spike in new cases, let’s hope July is the month they — and we — get the go-ahead. Hold your breath and bring your mask.

We had an initial burst of jubilation when the news hit that Music for a Sunday Evening in the Park (MUSEP) would indeed return for its 41st season — virtually. Kay and Adriel will open for the Philharmonia of Greensboro on July 19, and Sweet Dreams will open for the Knights of Soul on July 26. Both concerts will be streamed on facebook.com/CreativeGreensboro. The actual lawn-chair-in-the-open-air shows will kick off August 2 at Gateway gardens with West End Mambo and SunQueen Kelcey & the Soular Flares. More on the MUSEP series next month.

Further cause for optimism: Grove Winery in Gibsonville is scheduling shows (Bruce Piephoff September 6, for one), and I suspect others will follow suit.

Another venue that took the plunge is Bistro 150 in Oak Ridge. My gut tells me that restaurants and bars that feature open-air and/or patio stages, such as the Village Tavern and Summerfield Farms, as well as the big one, White Oak Amphitheatre, are chomping at the bit. And so are we.

Piedmont Blues Preservation Society folded its annual multi-act show in May into the N.C. Folk Fest September 11–13. If the huge, wildly successful festival goes off as planned, that will be the signal that the Zombie Apocalypse is nearing its end.

In the meantime, let’s all heed Jackson Browne’s sage advice to “let the music keep our spirits high,” whether live, recorded or virtual.

Ogi Overman

The Sporting Life

Beach Daze

When only O.D. and The Pad would do

By Tom Bryant

I grew up in the ’50s, and I believe the lifestyles during those wonderful times will never be seen again. World War II was over, with the slight exception of the police action in Korea. (Folks involved in that so-called police action would strongly disagree with the terminology — to them it was a war.) After that, the country settled into a cycle of prosperity not seen by the general population in a very long time.

In my own house, Dad was the single provider. Mom never worked outside the home. Raising four children was her full-time job. We had one car, and it was a family car, a 1957 Chevrolet station wagon, built to haul about anything. We weren’t poor, middle class maybe, but a long way from being rich. From the age of 13, I worked at one job or another every summer. Service stations, food stores, and finally Dad let me work at the ice plant, where he was manager. As a teenager, I earned my own spending money and helped with my college finances as well. But in the summer of 1959, I was a brand new graduate of those bastioned halls of higher learning at Aberdeen High School, and I was ready to celebrate.

College was right around the corner. In my mind, I had just graduated and was not real excited about becoming a freshman again. I had a pocketful of money I’d been saving, and two weeks of vacation before I had to report to Dad for summer work. There was for me only one destination during that off time, and that was the beach. Not just any beach but Ocean Drive Beach — better known as O.D. — and The Pad, better known as The Pad.

In our short time as teenagers, The Pad had become a tradition for several of my good friends and classmates, and graduation had added an extra emphasis on the importance of heading east. O.D. was calling.

Clifton and Graham, friends and also recent graduates of old AHS, were already there, supposedly on a scouting mission to find a place for us to stay for a few days, cheap. I was to meet them at The Pad at 3 o’clock Monday to begin our celebration.

The Pad was located on the corner of a street dead-ending at the ocean, right across from The Pavilion, an attraction in its own right. Home to games, carnival-type rides and snack bars, it also had a concrete dance floor and jukebox.

Both The Pad and The Pavilion were opened in 1955 and were mainstays at Ocean Drive Beach for fun and frolic. Structurally, The Pad wasn’t much, just a shed covering the bar and its sand floor and a square deck for dancing. I honestly can’t remember if the dance floor was wood or concrete. Behind the bar, washtubs were full of ice and cans of beer. In those days Pabst Blue Ribbon, PBR, was the most prevalent, and the wall surrounding the entire building was lined with empty beer cans. It was rumored that the wall was erected to hide dancers doing the shag, a six-count rhythm created by bands and music performed by groups like The Drifters.

All in all, The Pad and The Pavilion were the place to see and be seen, especially if you were young and in a party mood. As Harold Bessent, manager of The Pad for its last 10 years, said, “It became a sort of Mecca.”

Right on time, Graham and Cliff came sauntering out of the white sunshine glare of the beach into the cool shade. Chuck Berry was blasting “Johnny Be Good” from the jukebox, I was leaning against the bar talking to the on-duty afternoon bartender.

“Hey, Bryant, where’s your car? We didn’t see it outside. Didn’t make it down here?” Cliff was constantly chiding me about the car Dad had given me for graduation. Especially after he heard that it had two flat tires on the way home from the estate sale where Dad bought it. The old car, a 1940 Chevrolet Deluxe, served me well over the next several years.

“It’s parked around the corner. New tires,” I laughed. “Ready to go. What have you deadheads been doing? I hope you’ve found us a place to sleep. Cheap.”

“You won’t believe it,” Graham said. “Larry,” pointing to the bartender, “put us on to the Just-A-Mere-Guest-House, not two blocks from here. We left the car there and walked back. We booked us a room for three days, the only room they had available.”

That vacation week when we celebrated our graduation at The Pad and Ocean Drive Beach was one that we’ll never forget. We had a grand time. And at reunions ever after, it would always come up, “Do you remember that week at The Pad when Blue . . . ”

The Pad was torn down in 1994, not meeting the town’s requirements for safety and other things. The memories that old bar created for hundreds of young folks just beginning life after high school, would never be forgotten.

The ’50s and that restful, peaceful time were over. The unknown future lay on the horizon. There was the Cold War with Russia, the hot war in Vietnam, the technological race against other countries, and even perhaps against ourselves. I realize that when remembering the past, a person has a tendency to forget the bad stuff and just remember the good. My mother always said, “If you think the good old days were that good, try using an outdoor toilet when it’s 14 degrees outside.”

As a matter of fact, I think The Pad had outside bathrooms, and if I remember correctly, they were just a little better than what Mom was talking about. The difference, and a good thing for us, it wasn’t 14 degrees. OH

Tom Bryant, a Southern Pines resident, is a lifelong outdoorsman and PineStraw’s Sporting Life columnist.

Spirits

In the Mix

Pierre Ferrand 1840 shines

By Tony Cross

My introduction to cognac happened in the late summer of 2003. I had my first “front of the house” job at an intimate, independent French restaurant. It was small, and so was the staff; I was one of two servers. The owner, Raymond, was the chef, and his partner, Alan, was the sous-chef. Raymond’s wife, Ginette, ran everything up front. I began working there after they had been established for 13 years.

La Terrace was one of a kind. Usually on Saturday evenings, after all of the guests had retired to their homes, and the closing duties were finished, Raymond and Alan would sit at one of the two large round tables in the dining room, enjoying a snifter of Remy Martin cognac. I remember Raymond explaining to me how cognac is a digestif, a beverage (usually alcoholic) that helps you digest your food. He let me try it, and I’m sure I just shrugged it off. “What do you know? American punk.”

It was a mild rebuke, meant in the nicest way possible. Really. And he was right — all I cared about at the time was drinks, girls, and rock ‘n’ roll. Maybe not much has changed.

These days you can find a much wider variety of brandy on the shelves. Brandy is any spirit that’s distilled from juice. Pisco, armagnac and cognac are a few examples. Cognac is produced in the Cognac region of France, and there are six regions, or appellations, where the grapes are grown. The grapes are fermented after being picked and then double distilled in copper pots. The “eau de vie” is then aged in oak barrels.

Cognac is classified in three different categories:

VS (Very Special/Superior): Aged for at least two years in oak casks.

VSOP (Very Special/Superior Old Pale): Aged for at least four years in oak casks.

XO (Extra Old): Aged for at least six years in oak casks.

I’m not an aficionado by any means, so I’m not going to go down a list of cognacs and the differences/similarities in them. I will, however, recommend a great cognac for mixing cocktails. Pierre Ferrand 1840 Cognac is one of the most accessible and versatile cognacs on the market. At 90 proof, it’s great in mixed drinks. It has more of a backbone than Hennessey or Remy. And don’t get me wrong, I love Remy Martin.

I became aware of Pierre Ferrand five or six years ago, when I picked up Death & Company: Modern Classic Cocktails, by David Kaplan, Nick Fauchald and Alex Day (still one of the best cocktail books ever put into print IMO). “The Sazerac cocktail was originally made with cognac, until the European phylloxera epidemic in the late 1800s wiped out grape production and bartenders switched to rye,” they write, and go on to suggest using the 1840. One of the finest appellations in Cognac is Grande Champagne, and that’s where the Ferrand estate is located. Ferrand only produces Grand Champagne cognacs (which basically means they only use grapes grown from the soils of that appellation).

If you’re not into making cocktails, you can definitely enjoy this neat. I do. I purchased a bottle the other week, and as you’ll see in the picture above, what’s missing was enjoyed straight. It’s velvety and rich. I picked up notes of pear, lemon and spice; it has a pretty long finish. I don’t think this cognac was designed to be enjoyed neat, but it holds up quite nicely. The place it really shines is in cocktails, like the Sazerac. Some bartenders do equal parts cognac and rye — that’s probably my favorite build. I’ll leave you with the classic Sidecar cocktail recipe from the Death & Co. book.

Sidecar

2 ounces Pierre Ferrand 1840 Cognac

1/2 ounce Cointreau

3/4 ounce lemon juice

1/4 ounce cane sugar simple syrup

Garnish: 1 orange twist

Shake all ingredients with ice, then strain into a coupe. Garnish with the orange twist. OH

Tony Cross is a bartender (well, ex-bartender) who runs cocktail catering company Reverie Cocktails in Southern Pines.

The Pied Piper of Latham

How Jimmy Donaldson has endeared himself to his four-legged neighbors

By Nancy Oakley • Photography by Sam Froelich

It begins much like the Twilight Bark described in The 101 Dalmatians children’s book and the later Disney film adaptation: As the sun sets, the story’s canine protagonist, Pongo, sounds the alarm to the dogs of London that his litter of puppies has been stolen. His barking signal is picked up by Danny the Great Dane at Hampstead and his smaller yappy sidekick, then transmitted via water pipe by a Scotty to a normally sedate Afghan hound, who emits a howl from an attic window to a pet shop bulldog whose baritone woof is transmitted by a prissy French poodle atop a Rolls Royce . . . and so on until the evening air echoes with the sound of barking and howling. A similar phenomenon occurs every morning in Latham Park as the neighborhood pooches — Scooter, Milly, Archie, Cullen, Dixie and scores of others — respond to a familiar bird call with a chorus of “Woof! Woof! Woof!” that rises to a crescendo of “Roo! Roo! Roo!”

Their excitement stems not from the urgency of a dognapping caper, but the approach of the local Pied Piper, Jimmy Donaldson, his pockets laden with dog biscuits. “I’ve been feeding most every dog in the neighborhood for over 10 years, says the longtime resident who also sees “repeat customers” when his neighbors and their dogs walk by his house up the hill from the park.

Growing up in the Gate City, Donaldson has always enjoyed walking, having been part of an informal group that included the late Gene Johnston, a Greensboro businessman and U.S. House rep who lived on Granville Road. “We were called the G.I.R.L.S.,” Donaldson says with a chuckle: “The Granville International Relations and Lecturing Society. The Republicans would walk on the right side of the street, the Democrats on the left; we’d walk the golf course [at Greensboro Country Club],” he fondly recalls. But over time the group dissolved, and Donaldson, after enduring six bypass surgeries, knew he had to keep moving. His four-legged neighbors provided him with a solution.

Armed with dog biscuits, typically peanut butter-flavored, and a crow call used in turkey hunting (“The turkeys will gobble when they hear it,” Donaldson explains), the Pied Piper of Latham announces his approach. Babe, a black Lab who belongs to Sterling and O.Henry contributor Susan Kelly, serves as hostess of the neighborhood Welcome Waggin’ Committee, as she trots down the driveway, her tail beating like a metronome set on its highest speed. She stops to extend a paw as Donaldson leans down to give her a biscuit. He says Charlotte, David and Martha Howard’s Labradoodle, is arguably the most enthusiastic: “She wags not just the tail but the whole body!” Donaldson notes. “She’s more interested in the lovin’ than the biscuits.” Across the street is Jackie Prevette’s collie, Mokie. Once, when another dog had escaped the confines of his electric fence, Donaldson tracked him down with the crow call. He describes Tilly, the bird dog, as “standoffish,” but to see her bound across the yard at Donaldson’s call, you’d never know it.

Sandra Kay Reynolds’ three goldens, Gunter, Lucy and Lily “only need to hear me utter [Donaldson’s] name, and they rush to the door,” Reynolds says, adding that they once mistook real ducks paddling in Buffalo creek for his signature birdcall. “He’s like the ice cream man for dogs!” Reynolds observes. And indeed, the three cream-colored beauties fairly leap the fence at the sight of their own personal Good Humor Man. The admiration is mutual. “They’re so sweet and beautifully behaved,” Donaldson says with a wide grin.

On each excursion Donaldson clocks about 2 miles as he dispenses biscuits and affection to his community of canines — from Tim and Cameron Harris’ golden, Macy, to Kelly Rightsell’s dog who eagerly seeks out the biscuits through the slats of a fence. Charles and Kay Ivey’s beagle, Beau, is all wiggles when Donaldson ambles up the driveway. “I call him Elvis,” Donaldson says, as he bends down and commands, “Sing for me, Beau!” On cue, the aging dog launches into a strained but continuous baying. He ain’t nothin’ but a hound dog, after all.

On rainy days Donaldson makes his appointed rounds in his Jeep Cherokee, always stocked with treats; he estimates that he goes through 4 pounds’ worth a week. The dogs, he says, have all come to recognize the sound of the car’s engine. While en route to a recent fishing trip, he passed Reynolds’ house without stopping — much to Gunter, Lucy and Lily’s great disappointment.

All told, Donaldson says he’s fed and befriended some 45 dogs over the years — and a handful of cats, too — marveling at the distinct personalities of each. His routine “encourages me to live a healthy lifestyle,” he affirms. Perhaps more important: “It’s my joy in the morning.” And without a doubt, the dogs’ too. OH

Nancy Oakley is the senior editor of O.Henry.

Poem July 20

Buster Gets a Bath

When I pick him up

and tilt to the bathtub

he falls limp with shock

This cannot be. . . .

Then it’s dark thoughts

from dark eyes, the dog

I love so much hates me

A torture worse than death.

All sudsy now, scent of clover

and dead leaves washed away

with lavender and lemon.

How could you?

The sprayer — that cobra of doom

strikes again and again.

Even if it feels good

I’ll never say so.

After a brisk towel rub

he springs all over the house

a hero home from the war

The bath? It was my idea.

— Ashley Memory

Simple Life

By Jim Dodson

The last time I went to church was back in middle March.

Seems like half a lifetime ago.

On Sunday mornings these days — most days, actually — I’m out well before sunrise watering my gardens and watching birds.

The garden has become my church, the place where I work up a holy sweat and find — no small feat in these days of safe distancing and social turmoil — deeper connection to a loving universe. The arching oaks of our urban forest rival any medieval cathedral, and the birdsong of dawn is finer than any chapel choir. It’s the one time of the day when I feel, with the faith of a mustard seed, to quote the mystic Dame Julian of Norwich, that all will be well.

A rusted iron plaque that stood for decades in my late mom’s peony border reminded:

The kiss of the sun for pardon

The song of the birds for mirth,

One is nearer God’s Heart in a garden

Than anywhere else on Earth.

This well-loved verse is from a poem by Dorothy Frances Gurney, daughter and wife of an Anglican priest who reportedly was inspired to jot this particular stanza in Lord Ronald Gower’s visitor’s book after spending time in his garden at Hammerfield Penshurst, England. The poem later appeared in an issue of Country Life Magazine in 1913, gaining Dorothy Gurney a slice of botanical immortality.

Though I descend from a line of rural Carolina farmers and preachers, it wasn’t until I began roaming Great Britain as a golf and outdoors editor for a leading travel magazine in the late 1980s that the verdure in my blood asserted itself and my own passion for landscape gardening took root and began to grow like a Gertrude Jekyll vine.

In those days, it was my good fortune to write about classic golf courses and fly-fishing streams that happened to be near some of Britain’s greatest sporting estates and historic houses.

One of the first I visited in West Sussex was Gravetye Manor, the former home of William Robinson, the revolutionary plantsman who, despite being Irish, has been called the “Father of the English Flower Garden.” Robinson’s pioneering ideas about creating natural landscapes with hardy native perennials, expressed in his famous book The Wild Garden, became the bible of English gardeners and led to a gardening style now admired and copied all over the world.

I showed up there to stay one hot mid-summer afternoon when the 100 acres or so of woodlands and gardens were already past their peak. But like Dorothy Gurney, I was so taken with the sweeping natural landscape that I spent an entire day just walking the grounds looking at plants and chatting with the gardening staff. Among other things, I encountered my first Gertrude Jekyll vine, planted by Robinson’s protégé who went on to partner with Surrey architect Edwin Lutyens to create some of England’s most acclaimed private gardens.

After this, every time I traveled to England, Scotland or Wales with golf clubs and fly rod in tow, I made time to seek out some of the most historic houses and private gardens in the Blessed Isles. During bluebell season, I wandered through the breathtaking New Forest National Park to Chewton Glen — where farm animals by law walk free — and moseyed over to Kent to play a British Open course I’d always dreamed of playing. I also spent a blissful summer afternoon checking out the structural plantings of diplomat Harold Nicolson and the sumptuous gardens of his wife, author Vita Sackville-West at Sissinghurst, an ancient Anglo-Saxon word that means “clearing in the woods.”

I spent a day with Shropshire rose guru David Austin, toured the amazing terraced gardens of Wales’ Powis Castle, checked out the stunning gardens of Stourhead, Hidcote and Kew — even eventually found my way to Hammerfield Penshurst where Madam Gurney was moved to poetry. There I was so impressed by the riotous blue-and-pink peony border — my late mother’s favorite garden flower — I vowed to someday make my own peony border.

Back home in Maine, in the meantime, I cleared a 2-acre plot of land on top of our forested hill, rebuilt an ancient stone wall and began making my own mini-Robinsonian gardening sanctuary. My witty Scottish mother-in-law suggested I give my woodland retreat a proper British name, suggesting “Slightly Off in the Woods.” The name was apt. The garden became my passion.

In 2004, I set off to spend a year exploring two dozen private and public gardens and arboretums all over Britain and eastern America, learning that gardeners are among the most generous and life-loving people of the Earth. Among other things, I went behind the scenes at the famous Philadelphia Flower Show and England’s venerable Chelsea Flower Show, got to pick the brains of America’s most acclaimed gardeners at places like Brooklyn Botanic Garden, Jefferson’s Monticello, Pennsylvania’s Chanticleer and Longwood Gardens, and finished the year by spending six weeks with plant guru Tony Avent and three fellow plant nerds in the wilds of South Africa hunting rare species of plants. During this time I even helped design my first golf course and shape its landscaping, at times wondering if I’d perhaps missed my calling, though what is a golf course but a great big parkland in the tradition of Capability Brown?

One of the most surprising moments came when I called on John Bartram’s historic garden across the Schuylkill River from downtown Philly. I spent an enriching afternoon in the garden of America’s first botanist, learning that Thomas Jefferson frequently turned up in the garden during the long hot tumultuous summer he spent in Philadelphia composing the Declaration of Independence. According to Bartram garden lore, Jefferson jotted notes for his hymn of American democracy while reposing in the shade of a sprawling ginkgo tree on the grounds. The last time I checked, the ancient ginkgo was still standing.

For the Founding Fathers, gardening, agriculture and botany were elemental passions of life. As Andrea Wulf writes in her wonderful and prodigiously researched best-seller Founding Gardeners: The Revolutionary Generation, Nature and the Shaping of the American Nation, a tour of English landscape gardens — like the extended one I took — helped restore Thomas Jefferson’s and John Adams’ faith in their fledgling nation during some of its darkest hours. Gardening also helped make James Madison America’s first true environmentalist.

“The Founding Fathers’ passion for nature, plants, gardens and agriculture is deeply woven into the fabric of America,” she writes, “and aligned with their political thought, both reflecting and influencing it. In fact, I believe it’s impossible to understand the making of America without looking at the founding fathers as farmers and gardeners.”

My book on America’s dirtiest passion, Beautiful Madness: One Man’s Journey Through Other People’s Gardens — was my most fun book to research and write. Since its publication in 2006, I’ve heard from gardeners all over the planet and have made plans for a follow-up book on the diverse gardening passions of America and the adventures of an early 20th-century plant hunter and Asian explorer named Ernest Henry “Chinese” Wilson, whose discovered lilies are probably growing in your garden today.

As any devoted gardener knows, the beautiful thing about a garden is that it is forever changing and never completed. Revision and evolution go hand in hand with making a garden flourish and bloom.

As another July dawns in the midst of a worldwide pandemic and sweeping protests in quest of long overdue social justice and an end to racism, it strikes me that American democracy is really no different from the botanical wonders of the world.

A true gardener’s work is never complete, likewise for a true patriot of the diverse and ever-changing garden that is America. The garden must be tended regularly, weeded and watered, nurtured and fed, pruned and tended with a loving eye.

The good news is, gardens are remarkably resilient. They can take a beating, endure violent storms and punishing drought, yet come back even stronger than ever as a new day dawns. As Jefferson, Adams and that Revolutionary bunch knew, the one thing a healthy garden or democracy can’t abide for long is neglect and indifference.

And so, as mid-summer and our nation’s 244th birthday arrive, I plan to spend even more holy time in my garden — church until further notice — planning a new blue-and-pink peony border in memory of my late mama and thinking about what it means to be a good gardener and a true citizen of this ever-evolving garden we call America. OH

Contact Editor Jim Dodson at jim@thepilot.com.

The Omnivorous Reader

Going Viral

Shedding light on dark days

By Stephen E. Smith

In the mid-’90s, Richard Preston’s nonfiction The Hot Zone was a bestseller. Based on a 1989 outbreak of an Ebola-like strain of virus in Reston, Virginia, the horrors depicted in Preston’s book kept this reviewer awake at night. Even though the sickness was confined to monkeys imported for research purposes, it took an Army medical team clad in spacesuits to exterminate the infected primates.

With ample time to contemplate the predicament in which we now find ourselves, I did what reviewers do: I read, albeit belatedly, other books about pandemics. I downloaded Catharine Arnold’s Pandemic 1918: Eyewitness Accounts from the Greatest Medical Holocaust in Modern History, Sara Shah’s Tracking Contagions, from Cholera to Ebola and Beyond, Alfred Crosby’s America’s Forgotten Pandemic: The Influenza of 1918, and David Quammen’s Spillover: Animal Infections and the Next Human Pandemic (there are umpteen other equally enlightening volumes I haven’t had time to pursue), and I discovered in each book a blueprint for the COVID-19 pandemic — disturbingly precise roadmaps for events over which we might have managed a modicum of control on a worldwide, national and personal level had we taken to heart what history and science has to teach us.

If you’re interested in understanding the COVID-19 pandemic, Quammen’s 2016 Spillover is by far the most informative — and the scariest — study. He focuses on zoonotic diseases such as Ebola, AIDS, rabies, influenza and West Nile, infections that sicken animals and jump to humans. COVID-19, although not identified when Spillover was written, is a zoonotic that has escalated into a pandemic via human-to-human transmission, and Quammen makes it possible for the layman to comprehend the viral dynamic at work. He explains in straightforward terms how global travel and exploding world populations make it possible for a virus such as COVID-19 to spread rapidly. We tend to view the spread of such a virus as an independent misfortune that happened to us (how else would a nonscientist see it?), but “That’s a passive, almost stoical way of viewing them,” he writes. “It’s also the wrong way,” making us susceptible to anecdotal testimony and false cures that might be harmful.

Quammen says that emerging diseases are the result of two forms of crisis on the planet — ecological and medical. “Human-caused ecological pressures and disruption are bringing animal pathogens ever more into contact with human populations, while human technology and behavior are spreading pathogens ever more widely,” Quammen writes. Logging, road building, slash-and-burn agriculture, the consumption of wild animals, mineral extraction, urban settlement, chemical pollution, nutrient runoff into oceans — most of what we call “civilizing” incursions upon the natural world — destroy the ecosystem. This destruction releases viruses, bacteria, fungi, protists and other parasites embedded in natural relationships that limit their geographical range. “When the trees fall and the native animals are slaughtered, the native germs fly like dust from a demolished warehouse.”

In 2012 Quammen asked this straightforward question, “Will the Next Big One be caused by a virus? Will the Next Big One come out of the rain forest or a market in China? Will the Next Big One kill 30 or 40 million people?”

If we can’t predict the next pandemic, says Quammen, we can remain vigilant, we can monitor worldwide transmission, and take precautions. Argue as we may about how and why we got here, the fact remains we find ourselves in a frightening moment whose ramifications must be faced head on. Spillover allows the reader to do just that.

As thorough and graphic as the above-mentioned volumes are, they don’t truly immerse the reader in the personal misery visited upon the Spanish flu generation or on those of us suffering the most extreme ravages of COVID-19. But there are books of fiction — doses of focused reality — that do just that, books I’d read 50 years ago.

The first is Katherine Anne Porter’s 1939 Pale Horse, Pale Rider, a collection of three “short novels.” Told in the third person, the title story lulls the reader into the complacency of daily life — until the influenza sweeps up and almost kills the youthful protagonist. Porter’s description is worth reading in full, but here’s a sample:

“Pain returned, a terrible compelling pain running through her veins like heavy fire, the stench of corruption filled her nostrils, the sweetish sickening smell of rotting flesh and pus; she opened her eyes and saw pale light through a coarse white cloth over her face, knew that the smell of death was in her own body, and struggled to lift her hand.”

Porter suffered bouts of influenza at least three times in her life, so she writes from an acuity borne of experience, and she’s careful to impress upon the reader that we are all cursed with the conviction that nothing terrible can happen to us . . . until it happens.

If Porter captures the suffering endured by a victim of the pandemic, North Carolina’s Thomas Wolfe wrenches the reader’s soul when conveying the agony of watching a loved one die from the Spanish flu in Look Homeward, Angel. With Wolfe, the reader is always in danger of being consumed by his excessive wordiness, but it’s that verbosity that’s effective in conveying a terrible reality. Again, the writer’s words are worth reading in full, but here’s an excerpt:

“The rattling in the wasted body, which seemed for hours to have given over to death all of life that is worth saving, had now ceased. The body appeared to grow rigid before them. . . But suddenly, marvelously, as if his resurrection and rebirth had come upon him, Ben drew upon the air in a long and powerful respiration; his gray eyes opened. . . casting the fierce sword of his glance with utter and final comprehension upon the room haunted with its gray pageantry of cheap loves and dull consciences and on all those uncertain mummers of waste and confusion fading now from the bright window of his eyes, he passed instantly, scornfully and unafraid, as he had lived, into the shades of death.”

Books about death and disease don’t make for cheerful reading, but understanding the pandemic is better than succumbing to its ravages or losing a loved one to COVID-19. Wear a mask, wash your hands, social distance — and read wisely. OH

Stephen E. Smith is a retired professor and the author of seven books of poetry and prose. He’s the recipient of the Poetry Northwest Young Poet’s Prize, the Zoe Kincaid Brockman Prize for poetry and four North Carolina Press Awards.