Scuppernong Bookshelf

Light Reading

Brighten up the days with tales of lighthouses

By Brian Lampkin

Throughout this pandemic and isolation, the following lines from poet Allen Ginsberg have been echoing in my head: “Well, while I’m here I’ll / do the work — / and what’s the work?/ To ease the pain of living./ Everything else, drunken/ dumbshow.” At best, we’re all trying to ease the pain of living (and dying) as we struggle together through the COVID crisis, some of us very actively: nurses, doctors, of course, but also grocery store employees and all the other newly-realized essential workers in American life. As for the dumbshow, we’re not likely to forget the daily briefings.

For this column I tried to think of a job that epitomizes the work of isolation. What is the loneliest work on the planet? I settled upon a romantic notion: the lighthouse keeper. Now for the harder part: Are there books on lighthouses and lighthouse keepers that aren’t just coffee table showpieces? Enough for an entire column? We’ll see.

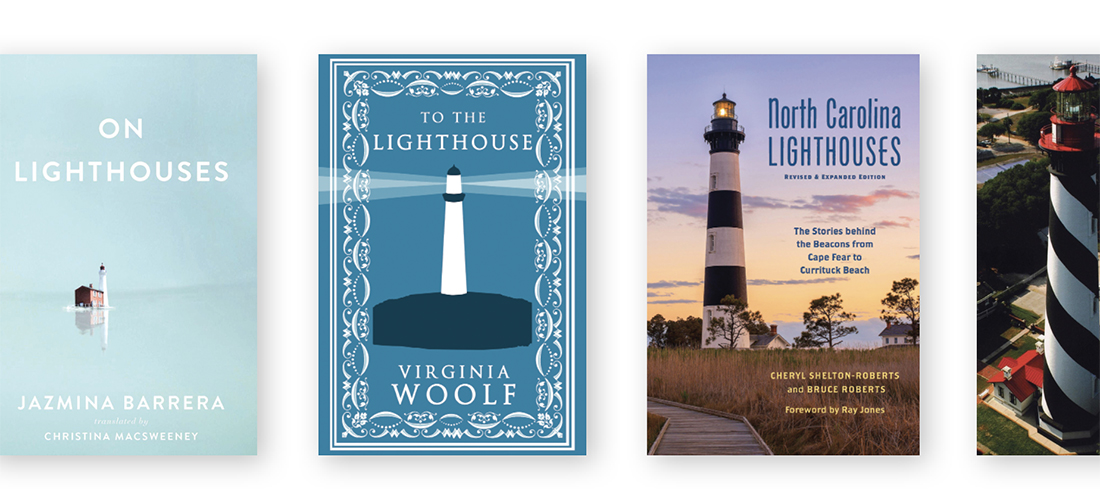

I can start with an absolute stunner. Jazmina Barrera’s new book, On Lighthouses (Two Lines Press, 2020. $19.95) has overwhelmed my pandemic-induced reading lethargy. Barrera’s work (part memoir, part essay, part story) is a thrill of passionately delivered lighthouse lore. It is also an example of literature as lived life — that reading and books and novels might infuse our daily existence with light and longing and mystery. “The lighthouse,” Barrera writes, “looks and searches, as a human being looks, a human being of stone.” She goes on to concur with 19th-century French historian Jules Michelet: “‘this guardian of the sea, this constant watchman’ is a ‘living and intelligent person.’” This short collection of lighthouses, translated from the Spanish by Christina MacSweeney, might convince you it’s true.

Barrera references the literary classic of the beacon field, Virginia Woolf’s To the Lighthouse (Mariner Books, $15.99). If you’ve been waiting for the right time to read this essential work, that time is here. The lighthouse on the Isle of Skye is the focal point for this look at a family in crisis and an early, accurate take on the tensions gender difference demanded. But it’s Woolf’s use of language that drives this novel into the wild sea.

Closer to home, UNC Press’ North Carolina Lighthouses: The Stories Behind the Beacons from Cape Fear to Currituck Beach (Revised and Expanded) (second edition), by Cheryl Shelton-Roberts and Bruce Roberts (2019, $22), considers the nine beacons watching over 300 miles of coast. From Cape Fear to Currituck Beach, every still-standing lighthouse is lovingly described alongside their architects, builders and keepers.

And what of those keepers? Those lonely persons who exert powerful romantic longings over so many who indeed would marry a lighthouse keeper and live by the side of the sea. There’s the straightforward Guardians of the Lights: Stories of U.S. Lighthouse Keepers, by Elinor de Wire (Pineapple Press, 1996. $21.95), which provides stories of the heroism and fortitude of the men and women of the U.S. Lighthouse Service, who kept vital shipping lanes safe from 1716 until early in the 20th century. But it doesn’t capture the existential loneliness that a novel might.

For that we turn to Jeanette Winterson’s Lighthousekeeping (Mariner Books, 2006. $16.95). The setting is the ominously named Scottish Cape Wrath lighthouse and includes a character named Babel Dark. But these Dickensian touches don’t undermine the ancient tales of longing and rootlessness as a young woman learns the lighthouse work while mining her own personal darknesses. And if you think the gender unlikely, you’ll need to check out Women Who Kept the Lights: An Illustrated History of Female Lighthouse Keepers, by Mary Louise Clifford, (Cypress Communications, $25.95). The book documents hundreds of American women who have kept the lamps burning in lighthouses since Hannah Thomas tended Gurnet Point Light in Plymouth, Massachusetts, while her husband was away fighting in the War for Independence.

Another historical fiction, The Lighthouse Keeper’s Daughter, by Hazel Gaynor (William Morrow, 2018. $16.99), closes our survey of lighthouse books. Gaynor tells two stories set exactly a century apart: 1838 Northumberland, England, and 1938 Newport, Rhode Island. It’s based on the real life of 19th-century heroine Grace Darling, lighthouse keeper and saver of souls in a ravaging storm, and explores the relentless longing of lighthouse life.

Two months into our experiment in social isolation, some of us have learned we could handle the lonely work of the lighthouse keeper and find joy. Most of us probably realize that it’s not the work for us. We must remain in this society and find our ways to be of use, to ease the pain, to be lights in the corona darkness. OH

Brian Lampkin is one of the proprietors of Scuppernong Books.

Hey faithful O.Henry readers! Scuppernong Books remains open in these isolating times for all orders: scuppernongbooks.com, email (scuppernongbooks@gmail.com) or phone call (336-763-1919). Starting in June we will offer “appointment browsing,” which will allow a limited number of people in the store for 30-minute visits by scheduled appointment. We will still be shipping books out to you and in most cases you’ll get your literary survival kit within a week. Please try to remember all of our small and local businesses during this continued social distancing.