Wandering Billy

“Just Plain” Joan

The Hollywood diva who always took Greensboro by storm around Mother’s Day

By Billy Eye

“The best time I ever had with Joan Crawford was when I pushed her down the stairs in Whatever Happened to Baby Jane.” — Bette Davis

SIXTY YEARS AGO: Eleven-year old Chester Arnold Jr. had acquired five shares of Pepsi common stock in 1957 but grew concerned about his investment. From his home on Cypress Street, he fired off a letter to Pepsi’s chairman Alfred Steele in

New York to ask if his board of directors was “crooked — like those people in the movie” he had just watched.

Steele’s new bride, film legend Joan Crawford, understood better than anyone the power of a finely executed publicity stunt. The boy and his parents were flown to The Big Apple and put up at the Waldorf Astoria for a whirlwind tour of the city. The Steeles planned a trip to Greensboro later that week would provide the perfect Hollywood ending to a real-life fairy tale — plucky small town boy meets glamorous movie star with the lights of Manhattan as their backdrop. After three days, the Arnold family traveled with the Steeles to Wilmington, Delaware, where a photo was snapped and dispatched to newspapers around the world; it showed young Chester, flanked by Crawford and her husband, as they attended a Pepsi board meeting.

The next morning, May 2nd, Joan Crawford, her husband Alfred and their entourage emerged from the 9:50 train at the Southern Railway Depot, where they were presented with keys to the city before crossing the street to the King Cotton Hotel to freshen up. Joan wore a simple white sleeveless dress with an enormous matching hat, as was the style of the day, for a 2 o’clock press conference announcing Pepsi’s newest, most modern bottling plant. At 4 p.m., Joan, Alfred, Pepsi executives and the Arnold family departed the King Cotton, escorted west down Spring Garden across Holden by a police motorcade. With sirens blaring, they roared up on a crowd numbering into the hundreds, some waiting for hours for the most elaborate ribbon cutting ceremony Pepsi had ever hosted.

FIFTY YEARS AGO: On the morning of May 5, 1967, a more jaded Joan Crawford greeted reporters at a Burlington press conference for which La Crawford arrived fashionably late (a popular Hollywood euphemism, widely adopted in the South, referring to some undefined moment existing between Bette Davis promptness and “Miss Garland’s not coming out of her dressing room.”)

Smartly dressed in a silk-lined, cinnamon colored linen jacket and matching shift, her upswept red hair tucked into an oversized fedora, Joan confessed in a drawl straight out of central

casting, “Last week at a housewarming for Donna Reed several people asked me where I was going next and when I said, ‘North Carolina,’ they said, ‘She already packed her Southern accent!’” Although there might have been just a nip in the air that Friday morning, there was definitely a nip in Miss Crawford’s air from sipping vodka throughout the day.

Crushing a spent cigarette under ankle-strapped high heels — the kind Joan Crawford wore so famously in the 1940s they became notoriously known as “come f**k me pumps”— the Academy-Award winner took great pains to portray herself as Just Plain Joan who entertained guests with home-cooked meals of breaded pork chops with fried apple rings and scrubbed the floors of her humble two-story penthouse shanty overlooking Central Park herself. It was Mildred Pierce redux with a side of cornpone, only now her precious Veda was a cold (but refreshing) Pepsi. “Every time you drink a Pepsi, I want you to think of Joan Crawford. If you drink Coke, you can think of those polar bears!”

FORTY-NINE YEARS AGO: Attending a May 18, 1968, Pepsi-Cola function in Charlotte, Joan posed for a photo with two locals, 11-year old Teresa Staley and George (Old Rebel Show) Perry, to promote the Muscular Dystrophy Association’s backyard carnival fundraisers. Teresa recalls being escorted into Crawford’s hotel suite, “The Old Rebel was super nervous and super excited about meeting her, but I was so young I didn’t have a clue. I was just excited about taking a road trip.”

“Quite a character,” is how she remembers the movie star. “Instead of pronouncing my name ‘Teresa’ she called me ‘Teraaaaasa.’ It was very funny. We spent a significant amount of time there, everything had to be just right to allow her picture to be taken.” The photographer captured George Perry gazing adoringly at the motion picture icon while Joan’s eyes remained fixed on a point somewhere in a galaxy far, far away. “She had just injured her ankle. She was wearing an Ace bandage but would not allow any pictures to be taken below her knees. I’ve worn glasses since I was 8, but she wouldn’t allow me to wear glasses in the picture because she was afraid it would cause a glare.” The thing that most impressed Teresa was, “Her bedroom door was open and her whole bed was covered with hats. I thought it was pretty cool that she traveled with all of her hats. And she carried her own ice on airplanes because she didn’t trust airplane water.”

No seminal Joan Crawford role would be complete without a no-good-deed-goes-unpunished ending, in this case the actress was unceremoniously dumped by Veda — er, Pepsi — on her 65th birthday.

It’s anyone’s guess how Crawford would have greeted the recent FX hit TV series based on her over-inflated rivalry with Bette Davis. Whatever her peccadillos and peculiarities, Joan Crawford was a wildly successful, widely admired businesswoman at a time when that was a genuine rarity, one who not only conquered the insidious labyrinth that is show business but also helped establish Pepsi-Cola as a multibillion dollar global powerhouse. If there’s any feudin’ goin’ on around these parts I’m obliged to take Joan’s side, thank you very much. OH

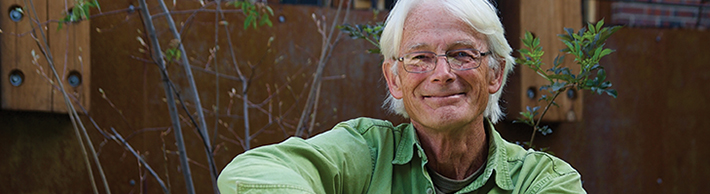

Billy Eye spent 15 years in the insidious labyrinth

of Hollywood before coming back to his hometown

of Greensboro.