A Walk on the Wild Side

A Walk on the Wild Side

Behind the scenes at the astounding Greensboro Science Center

By Jim Dodson

Photographs by John Gessner

A wise man keeps his child’s heart. Or so advised the ancient Chinese sage Mencius.

As I dip a hand in the waters of Hands-On Harbor at the Greensboro Science Center, where five cownose rays are gracefully circulating in their pool, a lovely female ray rises to the surface and allows me to touch her silken back.

For one sweet moment, my child’s heart is back. Schedules and deadlines suddenly fall away.

“Oh, wow,” is about all I can manage.

Both Erica Brown, the Center’s marketing manager, and senior aquarium keeper Karla Jeselson laugh.

“A lot of people have that response,” says Jeselson, explaining how the stingrays are naturally curious about human beings and conditioned to come to an orange ball at feeding time, twice a day, beginning with a full meal before the Center’s official 9 o’clock opening time, followed by an afternoon snack. As a result of such conditioning, the aquarium staff once managed to attach a stylus to the ball that permitted the rays to paint on canvas, images that are now sold in the museum gift shop.

“The little male ray is particularly good at art,” she confides. “We fish people don’t generally give names to our animals but between us, we like to call him Picasso.”

This charming introduction to the natural wonders — and constant surprises — of the Greensboro Science Center serves simply as the prelude to a delightful before-hours walking tour of the museum’s diverse exhibits that include the spectacular Wiseman Aquarium (named after former VF Corp. CEO Eric Wiseman and his wife, Susan), an outstanding Animal Discovery Zoo, not to mention the award-winning Science Museum, which vividly explores everything from dinosaur bones to the starry firmament. The three-in-one destination makes the museum unique in North Carolina and only one of 14 such facilities nationwide to earn accreditation by the Association of Zoos & Aquariums and the American Alliance of Museums.

My purpose in calling on the Science Center this cool morning is pretty simple.

First is to make up for lost time. After I left my hometown in 1977, chasing a journalism career that took me from New England to Africa, I missed the remarkable transformation of what was then called the Nature Science Center into a spectacular showcase of science, technology and the wonders of the natural world.

Paradise in our own backyards, as a close friend and proud member of the Center likes to say.

My only point of reference, in fact, was the Gate City’s original Junior Museum of Greensboro, so dubbed by the local chapter of the Junior League that established it in 1957. It was a decidedly modest affair that featured — if memory serves — a few science exhibits highlighted by a nearby petting zoo with a few woodland creatures kept behind chain link fences and live snakes on display, all set down in the forest of Country Park. I remember live deer, a fox, a few monkeys, an alligator and maybe even a live black bear being the star attractions.

As I confide to Erica Brown during our eye-opening tour of the Center’s 35-acre campus, I can’t believe what I’d missed.

“That’s something we frequently hear from people who’ve lived in Greensboro their whole lives but never checked us out,” she explains with another knowing smile. “When they see what is here, they’re always impressed and usually become regular visitors or members. There’s always something new to see and learn.”

In my case, impressed didn’t quite cover it.

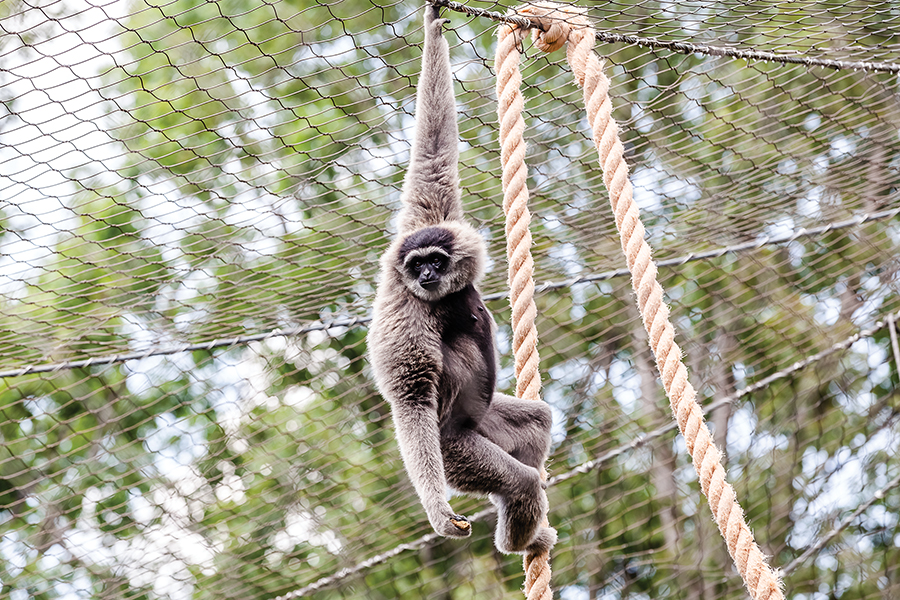

Over the course of a full morning, I see live sea horses, a mama Giant Pacific octopus straight out of Jules Verne and penguins being fed by hand. I meet Tai the red panda and Duke the silvery gibbon, exchange quizzical stares with a family of curious meerkats and watch a maned wolf doing his early-morning calisthenics in a patch of meadow sunlight. I see Drogo the komodo dragon and watch a female lemur named Reese receive her annual physical exam from staff veterinarian Sam Young and his able tech assistant. I also meet Sheldon the barn cat and Sidney the cockatoo, explore “Prehistoric Passages,” and learn interesting things about the human body in Health Quest Gallery.

Had I wisely thought to bring along my trusty knee brace, I might even have tackled Skywild, GSC’s extraordinary aerial adventure park, a roped obstacle course with seven different treetop challenge courses and three levels of difficulty that allow visitors and kids of all ages to get in touch with their animal spirits high over the forest floor.

Suffice it to say, having found the heartbeat of my own inner child again, however briefly, the other purpose of my visit is to hear from the Center’s indefatigable president and CEO, Glenn Dobrogosz, how this diverse and multifunctional wonder ship of science, nature and environmental sustainability came to pass.

Long a destination for local school groups and church field trips, the Center’s dynamic period of growth kicked into overdrive in 2000 when the voters of Greensboro passed a $3.5 million bond to create a new Animal Discovery Zoo, setting the scene for the arrival of a new president and CEO with even more ambitious plans in mind.

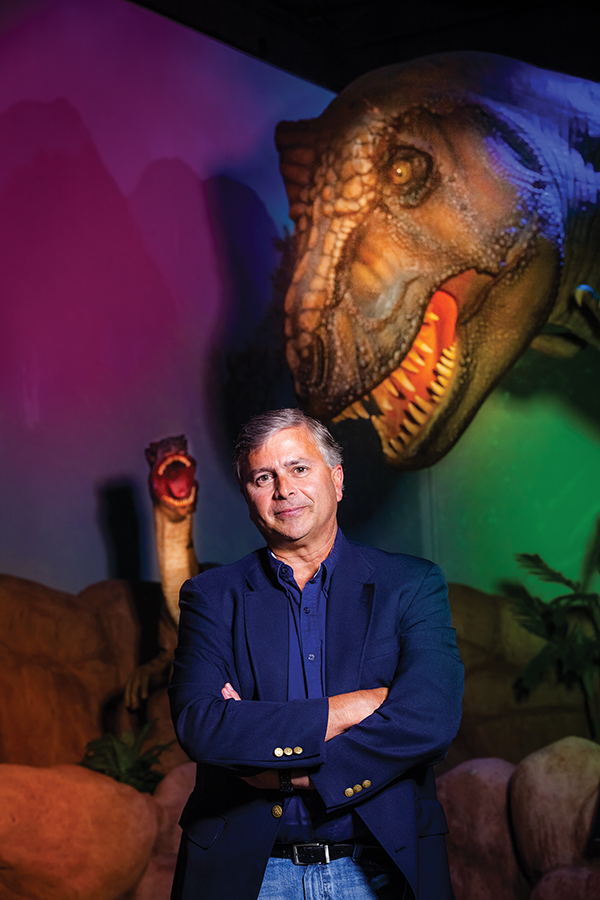

Appalachian grad and Raleigh native Dobrogosz arrived in Greensboro in 2004 with a resume that included the impressive revival of several leading zoos and a bold vision of growth that was supported by a board uniquely composed of forward-thinking civic, business and local foundation members, all of them eager to see the Center grow into a genuine destination park.

Animal Discovery Zoo opened to wide acclaim in 2008, doubling annual attendance from 125,00 to more than 250,000. One year later, an expanded planetarium that features 3D and laser projection technology also debuted.

The real watershed moment came in 2009, Dobrogosz says, when he approached the City Council with a long-range vision that included construction of an aquarium and a number of expanded exhibits that would make the Center, as he puts it today, “a one-stop shop for science, technology and environmental education.”

“If you recall that time,” he says, “the Great Recession had hit and Greensboro was still recovering from key economic losses going back further than that. It was, in short, a challenging time for everybody. The city was not your typical destination or tourist city.” He reels off the standard old jokes about Greensboro being “Greens-boring,” and suffering from “Charlotte envy.” But not everyone was laughing. “Then mayor [Yvonne Johnson, Greensboro’s current mayor pro-tem] and the council listened to our plan to create a signature three-in-one model that included North Carolina’s first inland aquarium combined with a zoo and asked how much we needed to make such a vision happen. Quite frankly,” he adds with a laugh, “I was taken by surprise.”

The result was a $20 million bond referendum that not only passed by a wide margin when it was placed before Guilford County voters that autumn, but also attracted a bevy of new corporate and private sponsors that funded the aquarium and enhancements of the Animal Discovery Zoo, setting new attendance records when the Wiseman Aquarium opened in 2013.

“It was really a gift to — and from — the people of Greensboro,” Dobrogosz adds. “But it was really just the beginning of what we hoped to accomplish.” He points out that in a city where tourism was never regarded as a major economic driver, the Center today is the No. 1 most visited attraction in Guilford County — a unique resource for the nearly half a million visitors who flock there every year now. Following an expansion of the aquarium that was completed in 2017, along with a newly reimagined dinosaur gallery, the Center broke attendance records yet again.

The big news coming out of the Center’s annual “See to Believe” Gala this past October? A capital campaign called “Think Big” that doubled its goal of raising $6 million to fund new educational programs and a major expansion called “Revolution Ridge — Life on the Edge.” Scheduled to open in 2020, it will connect the American Colonists’ fight for freedom among the fields and forests where the Center now stands, with the plight of endangered species across the globe.

The vision includes habitats for endangered pygmy hippos, an okapi forest for rare creatures called “forest giraffes,” a Cassowary Cove (strikingly large and dangerous birds from New Guinea), a Greensboro water garden, a greenhouse complex designed to educate visitors on plants essential to the survival of animal and man, a learning plaza with Chilean pink flamingos, plus a home for endangered cats called Precious Predators.

An expanded animal heath center will provide state-of-the-art medical care serving up to 1,000 wild animals, birds and reptiles. A new multiuse amphitheater, meanwhile, will host concerts, science programs and outdoor events of all kinds.

If everything goes as planned, the good news for Center stalwarts still grieving over the recent passing of the Center’s aging tigers, Axl and Kisa, will be a pair of endangered Malayan tigers in an expanded endangered tiger breeding center. Delighting kids of all ages, the campus will also be home to a world-class old-fashioned carosel funded by the Greensboro Rotary Club.

Finally, the campus’ current buildings will undergo a major architectural makeover that unifies the complex and allows space for public artwork. This year, the Center also acquired the former home of the Greensboro Council of Garden Clubs, scheduled to be transformed into the SAIL Center (Science Advancement through advanced Learning), a facility for educators, and a venue for lectures and seminars.

“It’s very exciting time at the Science Center,” Dobrogosz enthuses. “It’s amazing to think how far we’ve come, with a talented staff of more than 50 — many of whom come from this community — and hundreds of dedicated volunteers and docents who have come to love this place and do inspiring work with our visitors.

“In this respect, we are unlike any other facility in the state,”Dobrogosz contends, crediting his staff, the museum members and sponsors for making the Center a “primary destination” with a bright future.

Indeed, over the course of four hours I learn about monarch butterflies and howler monkeys, watch a 16-foot anaconda get fed her monthly rabbit, make meaningful eye contact with a shy fossa from Madagascar and learn about the conservation of coral reefs. A paradise indeed, as my friend had told me. But there is still so much to see and learn about.

My morning walk on the wild side ends far too soon, downstairs, where I chat with longtime curator of reptiles and invertebrates Rick Bolling about his 40-year career at the Center. He joined the staff in 1977 and will retire a few days after Thanksgiving this year.

“My first job was cleaning the glass of the snake enclosures. I thought that was very exciting work,” he remembers with a laugh. “When I got here very few people seemed to know about this facility. We were a nice little museum that educated schoolkids and gave people a taste of wildlife and science.”

The last 15 years, he says, have been nothing “short of incredible” thanks to Dobrogosz’s infectious “can-do passion.” “Over the years, he has brought much-needed energy and fresh vision to the zoo and museum,” says Bolling. “The education the public gets about conservation and animals and all sorts of science is nothing short of incredible.”

Bolling says that upon retirement he hopes to take a trip out to see Yellowstone National Park “before it burns up.”

Would he miss his daily life at the Center, we naturally wonder.

“Of course I’ll miss it! It’s been my life’s work and I count my blessings that I was a small part of our amazing growth over the years,” he says, gazing into the distance. “Every day here is different, always exciting, always new. This facility is really a big family that includes the animals and the people who support the Center.

“In fact,” he adds with a sly grin, “I’ve told everyone don’t be surprised if I come back to work as a docent. That way, I’ll never have to leave.” OH

Jim Dodson wrangles writers and editors in the zoo that is O.Henry magazine.