Birdwatch

Blue Streak

Listen for the sound of the blue grosbeak’s loud “chip” call this time of year

By Susan Campbell

‘Tis the season for the annual appearance of blue grosbeaks! Begin spotting this handsome, medium-sized songbird any day now along fencerows and on electric wires in rural areas throughout the Piedmont. Returning to the United States in April after long winter stays in Central America and the Caribbean, blue grosbeaks breed across much of America, from central California throughout the Plains states and up into Virginia. And now, ahead of migration southward to tropical wintering grounds, these chunky songbirds seek out easy seed sources in order to bulk up before the long journey south.

Although this bird is common throughout the Piedmont during the breeding season, it is often missed by casual observers. It is a bird of both pine and mixed forest, often encountered along edges associated with farming. Blue grosbeaks’ large silvery bill is what really makes this bird distinctive. The sexes are quite different, with males a dark blue. Also look for a small black mask around the bill and eyes, as well as chestnut wing bars. Females are more of a cinnamon hue than blue, with rusty wing bars and a bit of blue on the rump extending into the tail. Immature females have plumage very much like their mothers’.

Plumage counts. Some males in their first spring will not breed successfully because they do not have the extensive blue of fully mature males and are not able to attract mates in order to start a family. However, after a full year of singing, fighting and extensive experience foraging, they will become excellent prospects come their second spring as long as they survive the winter.

The blue grosbeak’s song is a rich warble, and their call a loud, metallic “chip.” Hearing these vocalizations is the best way to find them, given their propensity for spending a lot of time in thick vegetation. They prefer shrubbery for breeding, look for nests low in thick vegetation and viny tangles. The nest is a compact cup-shaped affair comprised of twigs, grasses, leaves and rootlets, often studded with paper, string or other litter. Blue grosbeaks are one of only a few migrant species that raise not just one, but two broods of between three and five young in a season.

Unfortunately blue grosbeaks all too often end up unwittingly raising the young of parasitic brown-headed cowbirds. Cowbird females are experts at laying eggs in the nests of other species found in open or semi-open habitat. The eggs, which are larger, generally hatch ahead of the hosts’ brood. They produce young that then grow larger and faster, oftentimes outcompeting the nestling grosbeaks.

Like most of our songbirds, this species feeds heavily on insects in the summer months. Caterpillars make up a significant portion of the diet. But blue grosbeaks also will hunt for food at or near ground level, collecting adult grasshoppers and crickets as well as other large insects. Their outsized bills are effective at breaking up prey items as well as large seed, such as sunflower kernels. Expect individual blue grosbeaks to show up at feeding stations soon — but they do not congregate the way other finches do. So keep an eye out if you live on the edge of town or in a more rural location. Spotting one of these distinctive birds is quite a treat! OH

Susan would love to receive your wildlife sightings and photos. She can be contacted by email at susan@ncaves.com or by phone at (910-695-0651).

South End Rising

Over the tracks, the far reaches of downtown are fertile ground

for new beginnings and a day’s perfect ending

By Quinn Dalton • Photographs by Brandi Swarms

Sunrise on the South End district lights the sky over Bennett College and spreads gold across Martin Luther King Boulevard, Arlington Street and South Elm, lengthening down Lewis Street. It’s late summer, the air already warming, and these few blocks, home to some of the city’s most diverse and unique shops, restaurants, galleries, workplaces and homes, are coming alive in ways few here could have imagined possible only a handful of years ago.

On the corner of South Elm and Bain streets, an armload of freshly baked French bread arrives at Chez Genèse. Storefronts open up, and chalked or printed sandwich signs appear outside to promote the day’s offerings. Elsewhere, the experimental museum where nothing is for sale but anything is possible, will soon open its entire storefront, where board-seat swings hang from the ceiling and beckon kids of all ages. A couple blocks over, the line’s out the door at Dame’s Chicken & Waffles, an anchor of Southside, just up the hill from South End.

South End? Southside?

Yes, there’s a difference, though they sit side by side. South End is Greensboro’s first and oldest downtown neighborhood, in recent years steadily renewed through the determined efforts of community organizers, developers, investors and entrepreneurs.

Bound to the west and north by the Southern Railway tracks as they curve toward the Depot, South End’s eastern border is Arlington Street. And the southern border of South End is pushing farther south all the time, past Gate City Boulevard and beyond.

Southside, right next door, is the new made to appear old — a visionary revitalization project funded by the City of Greensboro and born of extensive community involvement in the planning process. Bound on the north by Southern Railway tracks, on the west by Arlington Street, on the east by Bennett Street, and on the south by Gate City Boulevard, Southside occupies what has been traditionally known as Ol’ Asheboro, Arlington Park, the Asheboro Street neighborhood, and, most plainly, the South Greensboro neighborhood.

Taking cues from its older, funkier South End cousin, Southside’s mixed-use housing features retail or office space on the ground level and residential space above, as well as apartments, townhomes and single-family homes. There’s a mix of architectural influences from the urban south, including New Orleans–style, iron-laced balconies, Charleston-inspired two-level front porches, and historic ambience from warm-lit iron lampposts, smaller lots and sidewalks everywhere.

City funding also fueled renovations of historic homes that had previously suffered neglect. The resulting rebirth of Martin Luther King Boulevard now more properly honors its namesake. Formerly known as Asheboro Road, MLK Boulevard was mansion row in the late 1800s, with Queen Anne and Victorian confections rising to shelter the city’s professional elite — lawyers, bankers, etcetera — who could walk a pleasant few blocks to work in the growing number of tall buildings downtown. Several of these beauties still stand and are on the National Register of Historic Places.

Together Southside and South End comprise what was, and is, Greensboro’s first and only downtown neighborhood. And here’s the best part. You can feel all this time and transition surrounding you, not a line but a layering, like peering through a folded scarf — everything you see is tinged with the past. And there’s so much to see. So put your walking shoes on, people. Early bird gets to learn.

Southern, Charmed

In just a two-block stretch of South Elm, some half a dozen businesses are dedicated to helping you start your day feeling your best.

One of the newest editions, Sonder Mind and Body, opened just over a year ago. Owners Jessika and Veronica Olsen have popularized sensory deprivation tanks in Greensboro and brought together a collection of healing and health practitioners. Services include massage, acupuncture, Rolfing, hypnosis and more. The concept behind Sonder, it turns out, is “the realization that each random passerby is living a life as vivid and complex as your own.” This sounds like the motto for South End.

If it’s time to clean up your locks, On Point Barbershop delivers a precision fade. One waiting customer says of Willie Dowd, owner, “He’s the best. I go wherever he goes.” A few doors away, Rocks Hair Shop, promises “classic cuts, close shaves and craft beer.

But if you come in either place on a Friday or a weekend, be prepared to wait. Same is true for Boho Salon, which emphasizes natural products and processes. Or you can learn how to be on the other end of the scissors at Dudley Cosmetology University, which relocated to South End in 2013.

Then visit Vintage to Vogue Boutique, where a carefully curated collection of designer clothing and shoe brands await. Just few feet away you’ll find in Antlers and Astronauts’ handpicked treasures to adorn you and your home.

Founder Alexa Terry Wilde Reidsville native, wanted the store to be more than a place where people bought things. “The way we’ve set it up was very intentional,” she says. “We want people to come in and shop, but we also want them to feel like they can just stop in for a visit.” The couch, coffee table and upholstered chairs in the center of the space provide that very invitation, and, in fact, the entire store feels like a home, with its midcentury and ’70s influences. There are also events such as live music and classes featuring local artists. And the inspiration for the name?

“It’s a reflection of my husband’s and my different sensibilities, combined,” Wilde says. “I’m all about nature, the outdoors, so I’m the antlers. And he’s a science guy — the astronaut.”

As she’s gotten to know her customers, Wilde often sources with them in mind, just like the hand-selling you can expect in the world’s best bookstore, Scuppernong, by people who know books and know you (even if it isn’t on South Elm; it is in spirit).

Social Status has to be the most honestly named store ever. Devoted to all things sneaker, this South End store will hook you up with the latest in street fashion for your feet.

Across the street is Hudson’s Hill, which bills itself as an American general store dedicated to making and selling goods with purpose and meaning. And like everything else in South End, the new draws on the old. The two founders celebrate Made-in-America ethos with their carefully curated collection, focusing in particular on Greensboro’s denimed past. The name comes from Hudson Bros. Grocery, owned in the late 19th century by John Hudson, and the slight rise of land where the store was situated — hence, Hudson’s Hill.

Treasure Tracking

If the railroad tracks that mark the beginning of South End were once the line some really picky folks wouldn’t cross, let that metal border now be the sign that you’ve arrived where most of what you find can’t be found anywhere else.

Like Elsewhere, of the indoor swings, where you can also step inside a rose-lit teepee and inspect rows and rows of artifacts offering a new way of seeing and imagining. Saturday tours will start you on your journey. Or Terra Blue, which will celebrate 20 years in South End this fall, and will double in size with the acquisition of the other half of the building, adding class space for crafts like candle making, a salon and café space for people to gather.

And of course, the artists are here. They’ve been here, waiting for you. For 15 years Artmongerz has provided co-op space for artists to display their work. You’ll find all media, from paintings to photography, even room-sized sculpture. Photographer and co-owner Earl Austin says, “Even only a few years ago, when I told people where we are, their eyebrows would go up. Now we have more foot traffic than I’ve ever seen.”

A few doors away, Ambleside Gallery is also celebrating 15 years with a focus on paintings, drawings and sculpture. Owner Jackson Mayshark has been representing both established and emerging artists from throughout the world for nearly 40 years. Examples of local artists include Alexis Lavine and the late Leigh Rodenbough, who was an attorney for 51 years before turning his attention to painting in oil an pastel; water scenes — beaches, harbors — that make you squint in their sunlight. But Mayshark is also global, and his gallery displays works by British artists Nigel Price, Vicky Cox and Peter Archer, Chinese artist Guan Weixing, considered one of the world’s greatest living watercolorists.

Ambleside Gallery is one of only a few venues nationally that hosts the traveling exhibition of The American Watercolor Society. But the gallery also houses the ceramic works of Brown Summit–based brothers Bryan and Brad Caviness. Each piece, which looks from the outside like a piece of pottery with a crack or hole broken into it, hosts within a meticulously detailed miniature world — a Pueblo Indian settlement, a Moroccan town, a French streetscape. When asked what these treasures are called, Mayshark shrugs and smiles. “There isn’t a name for them. There isn’t anything else like them.”

Well, how about that.

And if you want to make your own treasure, then you need to come to Forge Greensboro Makerspace. Just go to the end of Lewis Street, hang a left, and look for the double doors with the sledgehammer handles. Whether you want to work in metal, clay or fabric, the tools and machinery you need are there. Even more important, there are people and classes to guide you in your creative journey. “We see ourselves as a gym for people who like to make things,” says executive director Joe Rotondi. “It’s not just the work but the creative collision that happens when you bring people together.” Tours are offered daily.

In the Spirit

Tired yet? If you’re ready to cool your heels and your throat, the options in South End keep growing — and just like their neighbor shops, boutiques, galleries and creative spaces, South End’s restaurants and bars each have their own distinctive feel. Mellow Mushroom came to South End a decade ago — and yes it’s a chain, but its success, and the reason it’s a perfect fit in South End, is because each ’Shroom is locally owned with a ton of creative control over the space. This is a cathedral theme, with arched, mushroom-themed stained-glass windows by Winston-Salem artists Veronica and David Bennett.

Across the street is a newer kid on the block, Chez Genèse. Open for breakfast and lunch, Chez Genèse serves up a warm blend of French-inspired comfort food and inclusivity — adults with intellectual or developmental disabilities comprise much of the staff and are paid a fair wage and benefits.

For dessert, why not be a kid yourself — in a candy store, naturally. Gate City Candy Company will take you back to the time when happiness was sugar on your tongue. Try a fresh daily selection of gourmet chocolates, fudges and peanut brittle (well, peanut brittle only if a certain writer doesn’t get there before you).

For the grownups, there’s The Bearded Goat, Horigan’s House of Taps, the Greensboro Distilling Company (the first legal distillery in Guilford County since Prohibition) which makes the wildly popular Fainting Goat Spirits, and next door, the SouthEnd Brewing Co. Across Lewis Street, Boxcar Bar + Arcade is family-friendly and very fun.

And then there’s The Hemp Source, which sells CBD products developed in a family business based in Wendell, N.C. Though they won’t get you high, different concentrations of the hemp-based product, in oral and topical forms, can provide pain relief and relaxation.

The Yellow Brick Road Leads to South End

The Community Theatre of Greensboro finally found its forever home in South End in 2012, when the Broach Theatre, named for one-time South End supporter and City Beat founder Allen Broach, became available. CTG is entering its 70th season and will mount its 25th production of The Wizard of Oz in November. Though Oz, its main fundraiser, is performed at Carolina Theatre to provide enough seats for the beloved annual production, the soul of CTG can be found through the red doors on South Elm. CTG is proof of the power of story brought alive on stage to thousands of actors and audiences of all ages, year after year. The Wizard of Oz involves a cast more than 100-strong. Multiply that by all of the families of those actors, and the volunteers, the staff and the audiences, and you can begin to imagine how big a heart CTG has to give to all of us. Just like its South End home.

The Believers

It takes faith to believe in something you can’t see. Maybe it takes even more faith to believe in something you do see, but no one else does.

A self-described Jersey street kid, Andy Zimmerman came to Greensboro in 1978 when his father moved the family furniture business to High Point. The move cut short his rabble rousing and introduced him to a new love — mountain climbing and kayaking North Carolina’s mountains and rivers. He soon found his own path to entrepreneurship with two kayak manufacturing companies, the latter of which he sold to his employees, who later relocated it to Arden, N.C.

In 2010, a friend asked him to look at a building downtown, which is now the home of. Greensboro Distillery and South End Brewery. Back then, it was a hulking shell. His friend asked him what he thought it would take to restore and upfit the building. “A million,” Zimmerman ventured.

“I’m out,” his friend said.

But Zimmerman needed to take on something new. The street-punk-turned-whitewater-thrillseeker was ready for his next challenge. He asked if his friend minded if he bid. Within the day the building was his, the first puzzle piece in what has become his life’s passion — the revitalization of South End. That was the start of Zimmerman’s new company, AZ Development.

His office is in the Lewis Street building that houses HQ Greensboro, a shared workspace with 24/7 access for members. It also features resources available to the public, including conference rooms with flexible layouts and state-of-the art technology, multipurpose rooms, and the ability to network and learn from other people who are starting something new. In just four years, HQ has come to house or support 80 companies and 130 tenants, who avail themselves of 25 private office suites and a well-stocked coffee bar. In time they’ll have company, as Zimmerman’s next project gathers steam: The renovated Gateway Center on the corner of South Elm and Gate City Boulevard, will welcome an estimated 230 employees in the coming months. The scale may be different, but the passion is the same. “I see myself as a place maker, not just a developer,” Zimmerman says. Bearing out his statement is a big deck in back of HQ, overlooking a beautiful secret garden laced with bloom-dotted narrow stone paths.

Executive director Kaitlin Smith says it’s become a thriving neighborhood space. “The folks at Elsewhere, our next-door neighbor, keep a vegetable garden here as well,” she says.

And that’s South End in a nutshell — a progressive workspace cultivating new companies right next to an experimental, nationally known museum born in a thrift shop — its products not things, but human imagination unleashed. OH

Quinn Dalton is the author of two story collections and two novels, most recently Midnight Bowling. She also co-authored The Infinity Of You And Me under the pen name JQ Coyle with fellow UNCG MFA grad Julianna Baggott.

Drinking with Writers

Coffee with Conscience

Best-selling novelist Amy Reed on Asheville writers, young adult

books and the challenge of living one’s values

By Wiley Cash • Photographs by Mallory Cash

There are countless humiliations specifically reserved for writers, from online reviews — Book arrived late. One-star — to empty chairs in the audience at a reading to sitting beside someone on an airplane who, after asking you what you do for a living, tells you he or she has never heard of you or your books.

One rarely discussed humiliation is the signing line. Signing lines can be lonely places for authors, especially during literary festivals when a much better known and beloved writer is signing hundreds of books at the table beside yours. Once, at a book festival in Nashville, Tennessee, I signed — which is to say I did not sign — books beside Bill Bryson. I also did not sign books beside Sue Monk Kidd at a literary festival in Florida. Last year, at the Doris Betts Spring Literary Festival in Statesville, North Carolina, I did not sign books beside novelist Amy Reed.

In early August, Amy and I sat down over coffee at Odd’s Café on Haywood Road in West Asheville, North Carolina, and I reminded her of our time together signing (and not signing) books at the festival in Statesville. Amy moved to Asheville from Seattle years ago, and she regularly writes at Odd’s Café, which, like most things in West Asheville, is odd. A few years back, the slogan “Keep Asheville Weird” appeared, and while Asheville as a whole has gotten less weird over the ensuing decade, West Asheville has maintained the city’s weirdness, its penchant for the arts, and an open invitation to artists of all kinds.

A stroll down Haywood Road in the heart of West Asheville reveals gorgeous murals painted on the sides of independent bookstores, coffee shops and hipster consignment stores. I feel more at home in West Asheville than I do in just about any other place in the country, and Amy Reed might just agree. Our conversation quickly turns to the city’s writing community.

“There are so many amazing writers here, especially young adult writers,” she says. She takes a sip of her coffee and gazes out at Haywood Road, where people pass in cars and on foot. The names of the local writers she rattles off next are a virtual Who’s Who of national and international bestsellers: “Alan Gratz, Alexandra Duncan, Stephanie Perkins, Beth Revis, and Jaye Robin Brown are just a few. Asheville’s writing community is so welcoming. Writing is a solitary profession, so it’s great when you’re able to connect with another writer.”

It is not just her colleagues in the local YA community that Amy has connected with. I remind her of the string of young people who waited in line to have their books signed at the literary festival in Statesville. Most of them were clutching a copy of her novel The Girls of Nowhere, which tells the story of three high school girls in Oregon who band together to fight back against misogyny and abuse at their high school, an act that transforms not only the students and their teachers, but their entire town.

I ask her why she thinks The Girls of Nowhere resonates with so many young people. “There’s just something universal about the teen experience,” she says. “When we’re teens we’re the most vulnerable and raw, and the stakes are so high. Teens want to read about themselves and their problems, and sometimes adults want to remember the teenagers they were.”

I agree. There is value in finding yourself on the page, and you can always return to the books you loved as a teen and find yourself there, which may explain adults’ sustained love for books like The Outsiders, Catcher in the Rye, and I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings.

I ask Amy what kind of reader she was as a teenager growing up in Seattle. She laughs and rolls her eyes. “I loved Anne Sexton and Sylvia Plath,” she says. “It was Seattle in the ’90s. Grunge was everywhere, but I was into female singer/songwriters. I was emo before emo was a thing. I was that girl.”

My two daughters, ages 4 and 3, are sitting at a table beside us, playing quietly. I confide to Amy that I consider my own books as time capsules that my daughters can read to discover who I was and what was important to me. I ask her if she thinks of her own books that way, as breadcrumbs she is leaving behind for her 6-year-old daughter so that she can know what her mother believed to be important and true.

“I do,” she says. “I try to live in a way that mirrors my values, especially now that I have a daughter. She was raised understanding that women and girls are strong and independent. I think she will find that in my books.”

Amy’s new novel, The Boy and Girl Who Broke the World, tells the emotional and humorous story of two young outcasts — an optimistic boy named Billy and a cynical girl named Lydia — whose bond may just save the world just as the world seems to be ending. Despite its surreal plotline, which involves a narcissistic rock star and a war between unicorns and dragons, the book is a lesson in honesty and vulnerability.

Apparently, writing about the apocalypse interested Amy enough to imagine a dystopian America in her next novel, which she describes as a near future gender-swapped, feminist retelling of The Great Gatsby set on an island off the coast of Seattle. “It’s very weird and dark and twisty,” she says. “In the novel, the world is falling apart, but the girl at the center of the book is able to find her own power.”

I’ll read it, and, once they are old enough, I’ll want my daughters to read it, too. OH

Wiley Cash lives in Wilmington with his wife and their two daughters. His latest novel, The Last Ballad, is available wherever books are sold.

Heartstrings

John Mark Hampton’s Moriah Guitars is an acoustic dream come true

By Grant Britt • Photographs by John Koob Gessner

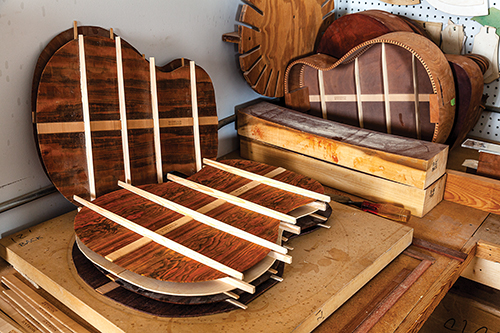

“Let me find somewhere to sit down and kinda blow off the dust,” Moriah Guitars’ proprietor John Mark Hampton says by way of greeting when you enter his space. Hampton has a sawdust nimbus hovering over his head, surrounding him with a slightly fuzzy aura that marks him as a luthier, a hands-on creator of one-of-a-kind stringed instruments.

Hampton creates his magic in a warren of rooms tucked away behind a tax and accounting service in a business park near Guilford College. Enter through the tax office lobby and wander through a labyrinth of expanding spaces littered with dismembered guitar body parts and tools like Paul Bunyan’s dentist might use to extract teeth. Lurking in the back of the warehouse-sized space are hulking machines the size of printing presses, resembling cast-iron behemoths lying in wait for prey to devour.

The process here seems to be a marriage of the old and new. “My philosophy is find the best way to do it, and don’t be anti-new,” Hampton says. “There’s lots of great stuff coming out with technology, but there’s also the old way where you have to take a tree and turn it into something, you know? It’s just a lot of processes.”

The Greensboro native kicked off his luthier career while attending Wilmington College in Ohio, taking an independent study at the Guitar Research and Design Center in Vermont in 1979. Returning to Greensboro from summer vacation with some of the guitars he built while in the program, Hampton approached Keith Roscoe, owner of the Guitar Shop, a guitar-building business on Tate Street. Roscoe gave the newly minted luthier an opportunity to build something for him that summer. “He just said, ‘Here — why don’t you just go in yonder and make me some guitars?’” Hampton recalls. “And I went to the drawing board and designed ’em from scratch. I made three electrics and one bass.”

He had been playing guitar since he was 13 and loved the sound and capabilities of the instrument. He also had a knack for woodworking. “When I got up to college, I had the opportunity to do anything I wanted, and I just shot for the moon, and said ‘What can I make?’ Just started like that, kind of like a dream to do it.”

Hampton was working for Roscoe, designing and building guitars when Ken Hoover started working there as well. Within a year, the two had left to start their own company, Zion Guitars, in 1980. “Ken and I just loved working together, and the chemistry was just really there,” Hampton says. “Bear in mind, I’m 62 now, and I was only 22, and Ken looked over at me one day and said, ‘How would you like to start a business?’ And I looked and him and said, ‘Uhhh . . . what do you mean?’ We just started off really from scratch, flying by the seat of our pants,” Hampton says, describing their shoestring operating budget as “nothing,” or next to it. “It was a real miracle,” he says now. “Ken believed in me and we just tried to do the best we could.” Gradually, service jobs and repair work for Triad area clients started to trickle in, and Zion Guitars started to gain a reputation by word of mouth.

The business took a flying leap forward the following year when Hoover and Hampton befriended Seymour Duncan, one of the first custom guitar pickup makers. Duncan invited Zion Guitars to a National Association of Music Merchants show in Atlanta, so the duo packed up one of their early prototypes they called a Tele-Zion Powerglide, a tribute to the Telecaster, and Duncan let them display it in his booth. The NAMM is the big dog of trade shows, attracting artists and dealers from all over the globe. Hampton was strolling around the showroom floor taking in the sights when he bumped into Kansas founder/guitarist/songwriter Kerry Livgren. “He was just looking around and I said, ‘Hey, are you Kerry Livgren?’ He said ‘Yeah.’ I said, ‘You might want to come see what we’re up to,’ and he graciously came over to the booth, saw the guitar we made, and ordered one on the spot,” Hampton remembers. That national artist link was a turning point for the young company. “[It] just of sort of grew little by little,” Hampton says. “We just knew some people, and they knew some people.”

Another giant step for the company occurred when Guitar Player magazine commissioned a guitar to put on the cover. GP editor Tom Wheeler was aware of the work of another Greensboro artist, Wayne Jarrett, who has enjoyed a career custom-painting guitars for the likes of Prince, Alabama, and .38 Special, as well as motorcycles. Wheeler asked him if he could do a custom paint job on a guitar to be featured on the cover of the magazine. “And Wayne, bless his heart, he said, ‘Tom, why don’t you get these local guys here in Greensboro to build the guitar, and I’ll paint it,’ and that’s how it all started,” Hampton recalls.

Seymour Duncan provided the pickups, and bridge makers Floyd Rose had a new tunable locking tremolo that graced Zion-manufactured Silverbird for the cover.

But just when the business was going great guns, Hampton decided to take a leave of absence. He says his heart’s desire “had always been to build acoustic guitars. I was feeling that we got things going pretty good with Zion and Ken was really wanting to take it into the electric zone. I felt like it was time to move on.”

So in ’84, Hampton left — to go to Scotland for what he described as “a worship and mission ministry” to do whatever the church over there needed. “I was going over to be a servant,” he says humbly of his service for New Life Christian Fellowship in Hawick [pronounced “hoyk”], Scotland. “They had a youth group I was helping pastor, leading the worship.” He met his wife, Eileen during his stay from 1985–1990, and when he returned, resumed his friendship with Hoover, who passed away last year from complications due to MS. During their renewed time together, Hampton designed and built the Zion Primera guitar, which attracted the attention of Christian guitarist Phil Keaggy, who signed some early models. Hampton started his own business, Moriah guitars in 2008.

“I had been a builder from 1990 up till 2008,” he reveals during a tour of his shop. “Building houses, and what we would do here, I would acquire tools along the way, kind of like gathering moss along the way, and here are the machines that sort grew little by little.” Then by 2008–’09 he felt like he needed to get back into building guitars again. “And my children were bugging me, they were telling me ‘Daddy, why aren’t you doing that?’ So that’s what started this. We built the shop and I’ve probably moved four or five times in the last 10 years. We’ve been here about four years.”

In one of the back rooms of his cavernous headquarters, Hampton is showing off some of his exotic woods. He pulls out a slab of beautifully grained quilted maple that looks like designs have been etched into the wood, but it’s just the natural grain. Acquiring the materials is a treasure hunt for the luthier. “You’re always looking out for something really beautiful. Sometimes we’ll find a board somewhere, or somebody will find something,” he explains. Like his friend who went on a surf trip down to Costa Rica brought back a board of rain tree wood. “I’ve made a few guitars off that,” Hampton says. “And sometimes we buy wood off suppliers who do make the wood prepared for guitar-building.”

Ironically, you’ll see no completed instruments at Moriah. “We’ve got a few bodies, just got ’em to this stage,” Hampton says of the stack of raw forms on a shelf. “We don’t have a contract on anything, so we leave it at a certain spot and people can come in and put whatever they want on it.”

Most of his builds are custom orders, which is great for business, but leaves no showroom models.

“I’m thinking of building a bunch of them just to have for people to look at. A lot of times people come here, and all the guitars I’ve built are already gone,” he says.

And even though Hampton says he doesn’t have any nationally known people among his clientele, he is building instruments for local friends and people who have known him for years. The commissions keep him busy. He says he’s got about 16 acoustic guitars in process — none of them finished. “But we’re working really hard to get ’em done.”

And Hampton has capitulated to some electric projects. But only a bit. “There’s always been a designing thing going toward the electrics,” he concedes, “but I’ve always wanted it to go to the acoustic. That’s been my dream. That’s what we’ve finally been able to do . . . that’s what Moriah’s about.” OH

Grant Britt peruses his own collection of trashcan-rescued guitars displayed haphazardly against the walls of his tchotchke museum across form the graveyard.

Benbow’s Beauty

A storied Fisher Park bungalow awaits its next caretakers

By Maria Johnson • Photographs by Amy Freeman

They’re caretakers, one pair in a series.

That’s the way Beth Nilsson and her husband, Carl, look at their 6-year ownership of the C.D. Benbow Jr. House, a broad-shouldered bungalow that perches on a rise overlooking historic Fisher Park.

“We have the best view in the park,” Beth says unequivocally. “You don’t know how many weddings and family pictures we see.”

The couple bought the stone-and-shake home in 2013, a hundred years after it was built, and moved in with their blended family of five children — “the Nilsson Olson Brady Bunch” as Beth calls them.

Now that the leading edge of their brood is maturing into adulthood — the kids are 21, 20, 19, 18 and 12 — the Nilssons have decided to sell the 3,400-square-foot Craftsman showplace and downsize to a smaller home. They’re not sure where they’ll end up, but they plan to stick with the eclectic neighborhood on the northern skirt of downtown Greensboro.

“Cookie cutter house? Forget it. We would never leave Fisher Park,” says Beth, who serves on both the neighborhood association board and on the committee that governs the leafy park.

The neighborhood, which took root at the turn of the 20th century, is a platter of architectural styles and contains a National Historic District. Clashes — such as the fray about whether the owners of Hillside, the recently renovated Julian Price House, should be able to operate a bed-and-breakfast with event space — are not surprising, Beth says. “People are passionate about living here.”

Like many homes in the area, the Nilssons’ place comes with a built-in backstory, one reason it landed on Preservation Greensboro’s Tour of Historic Homes & Gardens in 2017.

Beth flips the pages of a scrapbook. A snapshot shows a line of people standing from threshold-to-curb to get a peek inside. As with many old houses, there’s a pool of local people with connections to the house.

Beth has hosted nostalgic visits from a past owner and the granddaughter of another former owner. A herd of Greensboro folk have been friends and schoolmates of the children who’ve lived there over the years.

“Fairly frequently, someone will say, ‘Oh, I know so-and-so who used to play there,’ “Beth says.

The home was first populated by C.D. Benbow Jr. and Marjorie Long Benbow, who moved in soon after marrying.

Benbow was a grandson of De Witt Clinton Benbow, a major mover and shaker in Greensboro in the late 1800s. Born a Quaker near the community of Oak Ridge, D.W.C. Benbow was a dentist by training, but he left the tooth-pulling profession for real estate development and civic activism.

He was instrumental in establishing the forerunners of UNCG and N.C. A&T State University, and he saved the precursor of Greensboro College from financial ruin.

He attended the birth of the New Garden Friends Meeting, a Quaker congregation, and the incorporation of the Guilford Battleground Company, which preserved the Revolutionary War battle site, now a national military park.

He also built Benbow House, a four-story hotel at the corner of South Elm Street and what is now February One Place, the site of the International Civil Rights Museum.

When it opened 1871, Benbow House, with its tall, thin French-inspired windows, was lauded as a premium hotel. It hosted a band of northern newspaper editors on a tour of the “upper South” after the Civil War. The first person to sign the guest register was former governor Zebulon Vance.

The hotel burned in 1899. New owners replaced it with The Guilford Benbow Hotel, which was run by Benbow’s son, C.D.

A generation later, C.D.’s son, C.D. Jr., shunned the hotel business — he sold real estate and cars — but knew what fine accommodations looked like. He incorporated a taste for solid construction into his new Fisher Park home.

Famed local stonemason Andrew Leopold Schlosser almost certainly crafted the home’s battered-granite foundation and tapered piers, which are cemented together by Schlosser’s trademark grapevine mortar.

Schlosser’s handiwork distinguishes several Fisher Park homes, as well as the hardscape inside the park. Just across the street from the Nilssons’ home lies the so-called King’s Chair, a fanciful stone throne that was built in the 1930s and relocated to the park in 2014. Schlosser also wrought several of the stone bridges that span a creek in the park.

The Nilssons have spent many hours on their deep front porch gazing into the park and entertaining friends. When they married at Holy Trinity Church, wedding guests had only to walk a couple of blocks to a reception at their home.

When the couple celebrated Carl’s 50th birthday with a James Bond–themed bash, the front porch was given over to casino-style gaming tables.

Day-to-day, the family literally chills on the cool, concrete-floored porch, eating meals there and swinging in a wooden swing that they speculate was original to the house.

Inside, the home is expansive as well, with a wide central hallway flanked by living room, dining room, kitchen, and — a rarity for a Craftsman bungalow of that era — a first-floor master bedroom.

The Nilssons have renovated sparingly to preserve the home’s character.

“You couldn’t build a home like this today,” says Beth. “The amount of labor involved — it’s just not done.”

The Nilssons have left untouched coffered ceilings and pocket doors on the first floor, as well as the hand-sawn balusters that march up the stairs.

They didn’t dare touch the mural on the landing.

Depicting a seaside villa — perhaps on the Mediterranean — the undated mural is painted directly onto the plaster and framed with molding.

“Isn’t it fantastic?” says Beth. “I hope no one ever gets rid of that.”

The couple also kept original tile work where they found it. Brilliant blue geometrics splash across two bathroom floors.

To spotlight more original features, the Nilssons pulled up flooring that concealed hardwoods. In the kitchen, they patched and darkened the boards to conceal an incision across several planks.

Beth shrugs when asked the reason for the line. She doesn’t know or care.

“No one lives in a house like this unless they can stand a little quirkiness,” she says.

In the dining room, the Nilssons converted built-in bookshelves under a triple window to a marble-topped buffet with glass-front doors and glass shelves. Lights inside the cabinet show off a collection of Swiss glass and German porcelain.

Other upgrades include new kitchen cabinets, countertops and appliances, including two dishwashers; a glass-walled shower and fresh cabinetry in the master bath; and a powder room in what was previously a laundry room.

Geared for many inhabitants, the home has three-and-a-half bathrooms and up to seven bedrooms.

Many people would count four bedrooms, but Beth counts up to seven because the upstairs sleeping porch could be used as a bedroom and two of the upstairs bedrooms have walk-in closets big enough to turn into bedrooms, as the family has done.

“It’s really quite an interchangeable house,” she says.

The yard is flexible, too.

The Nilssons refreshed the sloping front yard, leveling and planting a second terrace between porch and street.

The downing of three oaks in the side and backyard in recent years has left room for whatever landscaping the next owners envision.

Ditto for the one-car garage and storage room — formerly a servants’ quarters — accessible by a drive-through port cochère on the right side of the home.

The tall steps leading from side porch to the port cochère speak of another time, when carriages might have wheeled up beside the house and needed a step that was level with a carriage.

Beth took a tumble off that step a few years ago, breaking her back — an injury that required rods and pins to fix — but even that did not dampen her love of the Benbow bungalow.

“I still love this house,” she says. “It brings a strong bond.” OH

Maria Johnson is a contributing editor of O.Henry. She can be reached at ohenrymaria@gmail.com.

O.Henry Ending

Jonni and Giorgio

How Norwood brought out the best in Hollywood

By Cynthia Adams

She may be

a Southern Belle, but cotton prints and housedresses were never her thing. Jonni “Jets” has a wardrobe suggesting a film star not a shut-in. (She won the “Jets” moniker from her grandchildren, given her love of travel, especially when involving nice hotels and shopping.)

Gold, lamé and sparkles are her basics.

Now topping the scales at 82 pounds, our little mama’s glitzy wardrobe is too large — even the extra smalls.

Last week, I opened the closet jammed with cruise-worthy finery, murmuring, “I have to help you clear this out.”

Then I paused: Where was the Giorgio Beverly Hills’ dress?

When my mother went through a rough patch some years ago, I suggested a trip, trying to incentivize her medical recovery.

Living up to her moniker, she suggested Vegas.

Not London, not New York. Jets wanted to do Vegas and got her wish.

On another occasion, after I was repaid an old debt, I was feeling flush and proposed another trip. Jets’ answer? L.A.

She turned her sites upon a city befitting a glamazonian, one who has spent more time in a hairdresser’s chair than Norma Desmond. I booked us into a classy B & B in Beverly Hills. Her head was entirely in the stars.

Upon arrival we learned actor Mickey Rourke demolished his room the prior night. My mom hissed, “Mickey who? Mickey Rooney?”

Her head swiveled around the lobby.

That afternoon I took her to the breathtaking Getty Museum. A spectacular flop for Jets, who slumped outside looking dejected, till I remembered whose trip this was.

I booked the Grave Line Tour (now the Dearly Departed Tours) featuring the last stops or “deathstyles” of the rich and famous. Mom sprang to life.

We walked Rodeo Drive. Mom gasped standing beneath the yellow-striped awnings of Giorgio Beverly Hills where Liz Taylor and Natalie Wood had shopped. Hooray for Hollywood!

With misgivings (all mine), we entered. Mom gasped with delight, her hand reaching for a bottle of Giorgio’s namesake fragrance. The staff sprang to action, spritzing her. She beamed.

The Giorgio’s people knew exactly what they were dealing with: two Southern ding-dongs unaccustomed to sipping bubbly when shopping.

To our utter delight, there was a major sale. Her red-carpet radar on full alert, Mom found a dress fit for the Oscars, replete with feathered boa. (They ship free! she breathed.) I bought nice towels.

With several flutes down the gullet, we shopped as if an entourage and a limousine awaited.

Inhibitions waaay down, I charged a leather skirt, jacket and a peculiar green hat that made me look like a dominatrix kitted out for St. Patrick’s Day.

Mom bought things ill-suited to her life back in N.C., but that was beside the point.

Pretty Woman’s version of shopping was wrong: Beverly Hills, like anywhere, rewards kindness. Nor did it hurt that my mother lavished praise.

The Giorgio dress was worth each luminous sequin and fluttery feather, although Mom never found a suitable occasion to wear it in Norwood. She resumed her life there, but breathlessly recounted the details of Valentino’s mausoleum, (maudlin), Lucille Ball’s home (modest), even Hitchcock’s iron gates with ravens (macabre.)

What did not disappoint were the beautiful people at Giorgio’s, and the dress.

And so, it remains in the closet, this thing of beauty. A joy forever. An utterly unnecessary essential. OH

Cynthia Adams is a contributing editor for O.Henry magazine.

Vine Wisdom

Cape of Good Wines

A feast of South Africa’s finest

By Angela Sanchez

South Africa is one of the most beautiful places I have ever visited, full of dichotomies, and singular in the world of wine. Whenever I mention its wines to people I get two types of responses — either they are excited to talk about South Africa and already love the wines; or they look confused and have no point of reference for either. But South Africa is near to my heart, and the wines are a great way to talk about the place, its people, its beauty and its history.

The Dutch brought vines to the Cape of South Africa in 1655, making it the oldest New World wine-growing region (North America, South America, Australia, New Zealand and South Africa making up the New World). It’s a long history but not always a great one.

During apartheid, the country was shut off from exchanging ideas, vines and modern innovations with other wine-producing countries. During that time, not only did South African vintners and growers miss out on a time of intense modernization and progress in the industry, many of their vines were diseased. Unable to bring in new, healthy vines to graft from or plant they often produced wines from diseased vines, resulting in inferior quality and taste.

Once apartheid ended, producers were able to travel, host and network with other vintners and producers around the world to replant their vines and modernize their facilities and winemaking techniques. It brought them not only into the modern age but also, in many ways, into a leadership role in the industry. Today South African growers and vintners partner with the government to ensure that not only are the wines and vineyards managed properly, fitting designated quality standards, they ensure that workers in the vineyards and wineries are treated fairly, with equal pay and protection. It’s a higher ethical standard than any other wine-producing country.

People are often shocked to find out that the Cape growing region has almost 550 active wineries. Of those, about 200 are registered to produce estate bottled wines, meaning the winery will be producing wines that come solely from their own vineyards — nothing will be purchased from other producers for those bottlings marked “estate.” A much smaller percentage, closer to about 50 wineries, actually produce wine that is truly estate bottled.

This is not to say that only a handful of wineries are producing good, or even great, bottles of wine. Many wineries and co-ops in the Cape are today producing some of the best values in the wine world. Chenin blanc, or “steen” in the Cape, is the most widely planted white grape varietal, and cabernet sauvignon is the most highly planted red. If you’re looking for fresh, easy-drinking styles that retail under $15-20 a bottle, seek these out.

For something truly unique, try a bottle of pinotage. It is a hybrid cross of pinot noir and cinsault created in South Africa, and can be a wonderful representation of place — earthy, smoky and jammy. Spice route pinotage is a generous style of this varietal. Dry farmed (without irrigation) in an arid and tough terrain from old vines, it produces a wine with briar fruit and dusty, peppery notes.

Each Cape growing region, or ward, is vastly different, one to the other. Drastic changes in elevation and topography make the wines and their characteristics as diverse as the regions themselves. One of the largest and best-known growing regions is Stellenbosch. The wines of this “district” are marked by the wide diversity of styles, driven by the different of types of soil, ranging from sandstone to granite. Two of my favorite producers for quality and value in the region are Neil Ellis and Man Vintners. Neil Ellis Stellenbosch Cabernet and Man Coastal Chenin Blanc are two great examples of amazing wines, showing distinct characteristics true to Stellenbosch while balancing a world-class line of quality between old and new world.

Another one of my favorite growing areas is Walker Bay, located in the Cape Overbay Region. Running along the “whale coast,” where the Southern right whale comes to mate, it’s a breathtakingly beautiful region. With a higher elevation and cooler climate than Stellenbosch, Walker Bay produces world-class chardonnay and pinot noir, especially from the area of Hemel-en-Aarde, meaning Heaven and Earth in Afrikaans. There are a few small estate producers in this highly distinctive region that are unlike any others in the Cape or the world. Cool Atlantic breezes and a fog that lingers over the vineyards keep the heat away, and the moisture around the vines helps produce the beautiful grapes that become such remarkable wines like those of Hamilton Russell Vineyards.

There are more growing regions in the Cape than I can possibly mention here. It’s home to species of flora and fauna that are not found anywhere else in the world, some of the oldest soils on the planet, and people determined to treat their land and people with respect, making it a dynamic place for growing grapes and producing wines — truly the best (blend) of Old and New World styles.

Welcome South African wines into your life and enjoy the diversity. OH

Angela Sanchez owns Southern Whey, a cheese-centric specialty food store in Southern Pines, with her husband, Chris Abbey. She was in the wine industry for 20 years and lucky enough to travel the world drinking wine and eating cheese.

Scuppernong Bookshelf

Tonight’s Homework: Graphic Novels

September sees several releases of the genre that has morphed from lowly to literary

Compiled by Brian Lampkin

The new school year brings a sweet reminiscence of comic books hidden inside text books as I pretend to pay attention to the weighty historical matter at hand. With apologies to “Old Sink or Swim” and “Wobbly Warren,” I was much more taken with Aquaman and the Silver Surfer.

In 2019, there’s no need to hide your comic art books. Graphic novels and histories have become respectable course work. Art Spiegelman’s Maus (1986) changed the way we think about the genre. Alison Bechdel’s Fun Home (2006) was recently named by The New York Times as one of the 10 best memoirs of any kind, and recent graphic interpretations of The Handmaid’s Tale, To Kill A Mockingbird and Kindred should be prominent parts of a literary education. September offers a handful of new works sure to enhance our understanding of art, history and literature, but isn’t it more fun to read them illicitly?

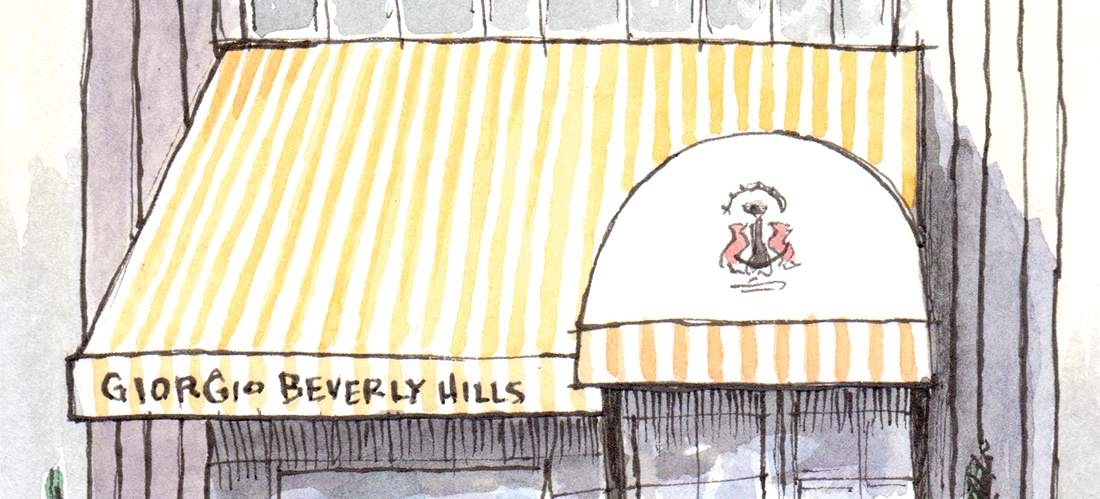

September 3: Animal Farm: The Graphic Novel, by George Orwell. Illustrated by Odyr (Houghton-Mifflin, $22). In 1945, George Orwell, called by some “the conscience of his generation,” created an enduring, devastating story of new tyranny replacing old, with power corrupting even the noblest of causes. Today it is all too clear that Orwell’s masterpiece is still fiercely relevant wherever cults of personality thrive, truths are twisted by those in power and freedom is under attack. Now, in this fully authorized edition, the artist Odyr translates the world and message of Animal Farm into a gorgeously imagined graphic novel.

September 3: Fever Year: The Killer Flu of 1918, by Don Brown (Houghton-Mifflin. $18.99). What made the influenza of 1918 so exceptionally deadly —and what can modern science help us understand about this tragic episode in history? With a journalist’s discerning eye for facts and an artist’s instinct for true emotion, ALA Sibert Award nominee Don Brown sets out to answer these questions and more in Fever Year.

September 10: Atar Gull, by Fabien Nury. Illustrated by Bruno. (Titan Comics, $24.99). Nury is an award-winning French comics writer, with early successes such as Once Upon a Time in France, for which he received the 2011 prize for best series at the Angoulême International Comics Festival. He is most recently known for the original graphic novels The Death of Stalin (which was the source material for the 2017 dark farce film of the same name) and Death to the Tsar.

September 10: Punks Not Dead, Vol. 2: London Calling, by David Barnett. Illustrated by Martin Simmonds (Black Crown, $17.99). In the 1980s and ’90s, graphic novels lived in the underground music and political activist scenes. Tripwire magazine says, “[The] brilliantly realistic art of Martin Simmonds . . . is dripping in punk rock attitude . . . that pushes everything in London Calling up to eleven.” Graphic novels not dead.

September 24: The River at Night, by Kevin Huizenga (Drawn & Quarterly, $34.95). Huizenga uses the cartoon medium like a symphony, establishing rhythms and introducing themes that he returns to, adding and subtracting events and thoughts, stretching and compressing time. A walk to the library becomes a meditation on how we understand time, as Huizenga shows the breadth of of the medium of comics in surprising ways. The River at Night is a modern formalist masterpiece as empathetic, inventive and funny as anything ever written.

September 24: Excuse Me: Cartoons, Complaints, and Notes to Self, by Liana Finck (Random House, $20). Excuse Me assembles more than 500 of her best-loved cartoons from Instagram and The New Yorker over the past few years, in such distinctive chapters as: “Love & Dating”; “Gender & Other Politics”; “Animals”; “Art & Myth-Making”; “Humanity”; “Time, Space, and How to Navigate Them”; “Strangeness, Shyness, Sadness”; and “Notes to Self.” Melancholy and hilarious, relatable and surreal, intensely personal, yet surprisingly universal, Excuse Me brings together the best work so far by one of the most talented young comics artists working today.

October 1: The Best American Comics 2019, Edited by Jillian Tamaki (Houghton-Mifflin, $25). The Best American Comics 2019 showcases the work of established and up-and-coming artists, collecting work found in the pages of graphic novels, comic books, periodicals, zines, online, in galleries and more, highlighting the kaleidoscopic diversity of the comics form today. OH

Brian Lampkin is an owner of Scuppernong Books and the author of The Tarboro Three: Rape, Race, and Secrecy.

In The Spirit

Good Ol’ Rittenhouse

Rye whiskey that was love at first sip

By Tony Cross

Anyone in the bar business is well aware of Rittenhouse Rye. It is, without a doubt, the best bang for your buck mixing rye whiskey on the market. Rittenhouse’s popularity comes with a price (and not attached to a dollar sign); it’s hard to find. Granted, it’s currently sitting on the shelf of the closest ABC to me. The question is: For how long? If you’re a fan of anything from old-fashioneds to Sazeracs, drop what you’re doing and call your local ABC right away and have them hold a bottle for you. Chances are, they’re already sold out.

I became familiar with Rittenhouse almost a decade ago when I first dived into the world of making drinks. A couple of recipes from well-known bartenders called for Rittenhouse when a rye was needed. Our ABC wasn’t carrying it at the time, and never had. The only way for me to get my hands on it was by ordering a case. I was managing a restaurant at the time, and had just become the main bartender. A case of rye that I never had before was a little risky, especially with a $360 price tag. Luckily for me, it was love at first sip, and before I knew it, that first case was almost gone! It was a few cases later when my local ABC hub informed me that they were going to stock the rye. The combination of my case orders and myriad customers (that frequented my bar) requesting the whiskey seemed to get the ball rolling. Not that I’m responsible for Rittenhouse having a (semi) permanent spot on my local store’s shelf . . . I’m just saying.

Rittenhouse Rye was founded in 1934 in Philadelphia, and was started after Prohibition ended in December 1933. It was named after the American astronomer, mathematician, inventor (and on, and on), David Rittenhouse. Originally titled “Rittenhouse Square Rye,” it was named after one of William Penn’s squares in Philly that was originally called “Southwest Square” but later renamed “Rittenhouse Square” as a tribute to David. It is currently produced in Kentucky by Heaven Hill Distillery.

Rittenhouse is a bonded rye; you’ll see “Bottled in Bond” on the label. At the end of the 19th century, there were a lot of distillers popping up everywhere that were selling, well, crap hooch. Bankers and other higher-ups with money started lobbying Congress; they wanted a law that guaranteed that their spirit was of high quality. Thus, the Bottled-in-Bond Act of 1897 was born. Whiskey from there on out was to come from one distillery during one distilling season, and had to be aged in a federally bonded warehouse for at least four years, and bottled at 100 proof. I’m sure that most politicians sent this bill through quickly for personal reasons as well. Not complaining. The tradition continues, as every bottle of Rittenhouse is bottled in bond.

Today, we are lucky to have a huge selection of rye whiskeys to choose from. Even if our local ABC store doesn’t have a great offering, you can always explore other state’s liquor stores, and/or shop online. With that being said, you can never go wrong with Rittenhouse. It’s great neat, on the rocks, or in classic cocktails.

Personally, I’ve always gravitated toward rye whiskies when it came time to make most whiskey forward cocktails. The first proper cocktail I ever made was a Manhattan. When I was behind the stick, no matter what time of year, I always had a Manhattan on my menu. And it was made with Rittenhouse. It’s spicy, but not over-the-top. It’s got a touch of sweetness, but nothing compared to a bourbon. It’s the best. There are other ryes that I love, but Rittenhouse will always be a staple in my bar.

When I was sitting on my first case of Rittenhouse, I had at least three or four cocktails on my menu with rye. I was trying to get our guests to give classic cocktails with whiskey a shot. This was at a time when neon-colored drinks were popular and every other menu had “tini” printed on it with vodka as the spirit. I wanted people to understand why classics are just that. Rittenhouse helped, from our Sazeracs to our sours. “I never liked whiskey drinks, but this one is delicious!” was starting to become common buzz. If memory serves, we added a New York Sour to the menu the first fall that I was behind the bar. Off the bat, it was aesthetically appealing, which usually got a group of our guests talking when someone from the table ordered it. After sharing a few sips, more orders would follow suit.

New York Sour

2 ounces Rittenhouse Rye

3/4 ounce fresh lemon juice

1/2 ounce simple syrup (2:1)

1 egg white (optional)

1/2 ounce red wine (I used malbec)

Lemon peel to garnish

Combine rye, lemon juice, simple syrup (and egg white if you choose) into a cocktail shaker with ice. Shake hard for 10 seconds (longer with egg whites) and strain into a rocks glass with ice. Using the back of a bar spoon, slowly float the red wine atop the cocktail. Garnish with a swath of lemon peel. OH

Tony Cross is a bartender who runs cocktail catering company Reverie Cocktails in Southern Pines.