Green Acres

Living above The Farmer’s Wife, proprietor Daniel Garrett enjoys both country and urban living

By Billy Ingram • Photographs by Amy Freeman

Would you believe me if I told you there’s a charming country home downtown, just steps away from Hamburger Square? As Daniel Garrett, owner of this urban oasis put it, “You can take the farm boy off the farm, but you can’t really get the dirt from underneath the fingernails.”

Garrett is purveyor of The Farmer’s Wife antique store at 339 Davie Street the cream filling in the only cluster of storefronts that survived a series of fires in the 1980s that wiped clean the Davie Street business sector. The area was once a thriving district with two- and three-story buildings on both sides of the avenue rivaling those on South Elm, one block west.

Garrett recalls, “My neighbor told me the story that, when the big fire was across the street where they were in the process of building [Greensborough Court], he said he got on top of his building and hosed it down, afraid that sparks might jump the street and spread to here.”

Garrett established his original antiques boutique on South Elm. His shop opened doors in the middle of a struggling downtown between Lewis and Lee streets (now Gate City Boulevard) in 1982, when just about every other downtown establishment had migrated to shopping centers and malls in the suburbs. “When I first started the business 36 years ago,” Garrett tells me, “you could rent a building on South Elm for $300 or $400 a month for a good sized-space. Of course, now people want $1,200–1,500 or more.”

It was a different environment then. “We were moving into a wholesale antiques district, and we knew that, there was no retail,” he says. “It was out-of-state people coming to buy items then take them somewhere else to sell for more money.”

Garrett had a notion to own a place of his own downtown, so when his neighbor on Davie told him about the building next to his being foreclosed on in 1994, that it was to be auctioned off to the highest bidder, he decided to check it out, mostly out of curiosity. “There were about 25 or 30 people there.” To his surprise, “At the end of the auction I was the last one to bid. It was serendipity, I guess.”

Built around the turn of the 20th century, this former grocery wholesale distribution center is crowned with a decorative, galvanized metal cornice. The upper two levels are fronted in brick, accented with limestone trim above and below the windows.

To call the purchase a fixer-upper would be a laughable understatement. After years of neglect, it was — how shall I put this politely — a dump. The kind of place you’d deposit a dead body if you didn’t want it found.

It was a roll of the dice. Downtown wasn’t the most hospitable environment back in the mid-1990s. Daniel Garrett recalls, “That first year I had power tools stolen, paint stolen.” After Southside and City View Apartments went up on the other side of the tracks, and the train depot was resurrected to serve as an all-purpose transportation hub, “It all became a little bit more gentrified, you might say,” he says.

This home is remarkably quiet considering it’s situated practically on top of the railroad tracks. When I told him one of the reasons I enjoy living downtown is the sound of the trains, Garrett replied, “Well, you have to love the trains because they’re right there.” Indeed, the reason for this cluster of four buildings’ very existence was proximity to the rail yard, the original Southern Railway system’s freight depot was located right next door.

It’s a bit of a mystery as to the exact date this place was constructed. The first tenant I can pin down was George T. McLamb wholesale grocers, who moved here from Lewis Street in 1906. McLamb’s neighbor at 337 Davie, in a nearly identical building, was the National Biscuit Company, one of over 100 satellite bakeries for the company we now know as Nabisco.

McLamb closed up shop around 1912. Another wholesaler, Transou Hat Company, traded chapeaus at 339 Davie before the address was once again home to a succession of wholesale grocers beginning in the 1920s until the mid-1960s when the building was vacated. Primarily used for storage after that, for brief periods in the 1980s it housed a college professor or two.

Entering the living areas on the floors above the street level storefront is like stepping into a country farmhouse that somehow sprouted in the heart of the city. Raised in Pleasant Garden where, as he put it, “You’re related to everybody and everyone knows your business,” the décor reflects Garrett’s small-town upbringing. His grandfather made one of the tables and two of the cabinets in this living room.

You would think an old structure like this would be dark, but it’s remarkably bright inside. Large picture windows to the front and rear flood the rooms with natural light. Plus, Garrett cut a horizontal window into the living-room wall to take advantage of sunlight emanating from a skylight on the other side.

A heavy eight-paned garage door slides to one side, leading to another wing of the home used mostly for storage. “We had to do things a little at a time,” Daniel explains. “I didn’t have the money to just do everything at once. I replaced windows one or two at a time.” A new roof was needed, the electrical wiring and plumbing had to be redone, “I had a very small budget to rehab the building. So when that money ran out we had to stop.” A new kitchen was installed about five years ago.

The store’s original front doors were flat and drab so a more inviting entrance with an Italianate feel was created. The project was a familial effort, “My brother-in-law, who had just retired from the post office, was a huge help at that time. He was wanting projects to do and he was one of those persons who was handy and could do things like that.” Until five or six years ago, off the kitchen, a dilapidated freight elevator sat stuck in place, “My brother worked for an elevator company and he said, ‘You’ll never get this to pass inspection’ so it was removed,” Garrett explains.

His bedroom on the floor above is one enormous warehouse-sized space with a 25-foot-high ceiling and three massive picture windows on the western-facing wall that overlook the park across the street behind Natty Greene’s.

As for the impressive and ubiquitous exposed brick walls and lightly colored hardwood floors, Garrett says, “This is exactly the way it was before I bought it, I haven’t unpainted or repainted the brick.” Because 341 Davie was built first, his southern-facing wall was that building’s exterior wall. The floors are imperfect but, “I’m leaving them that way. I can live with imperfection,” he allows. “I’d rather have it the way it was, and how it was used, versus getting too slick or sophisticated.”

A mirror in need of resilvering is a favorite item. “I like that one because it doesn’t make me look as old. It’s so fuzzy, it doesn’t necessarily tell the truth,” Garrett jokes. Numerous wooden architectural touches from building exteriors lend both scale and intimacy to these cavernous spaces. Pointing to a large mantel positioned just below the bedroom ceiling, Garrett explains its provenance: “I bought that in Liberty, North Carolina, years ago. It’s actually the cornice from the top of a building that I had mounted to the wall.”

A large armoire stores dishes and glassware, because, “You have to have big things in a room this large; if you have a bunch of little things they just get lost,” Garrett notes, adding, “That’s why I did this line of prints down low, to pull the ceiling down to a more human scale.”

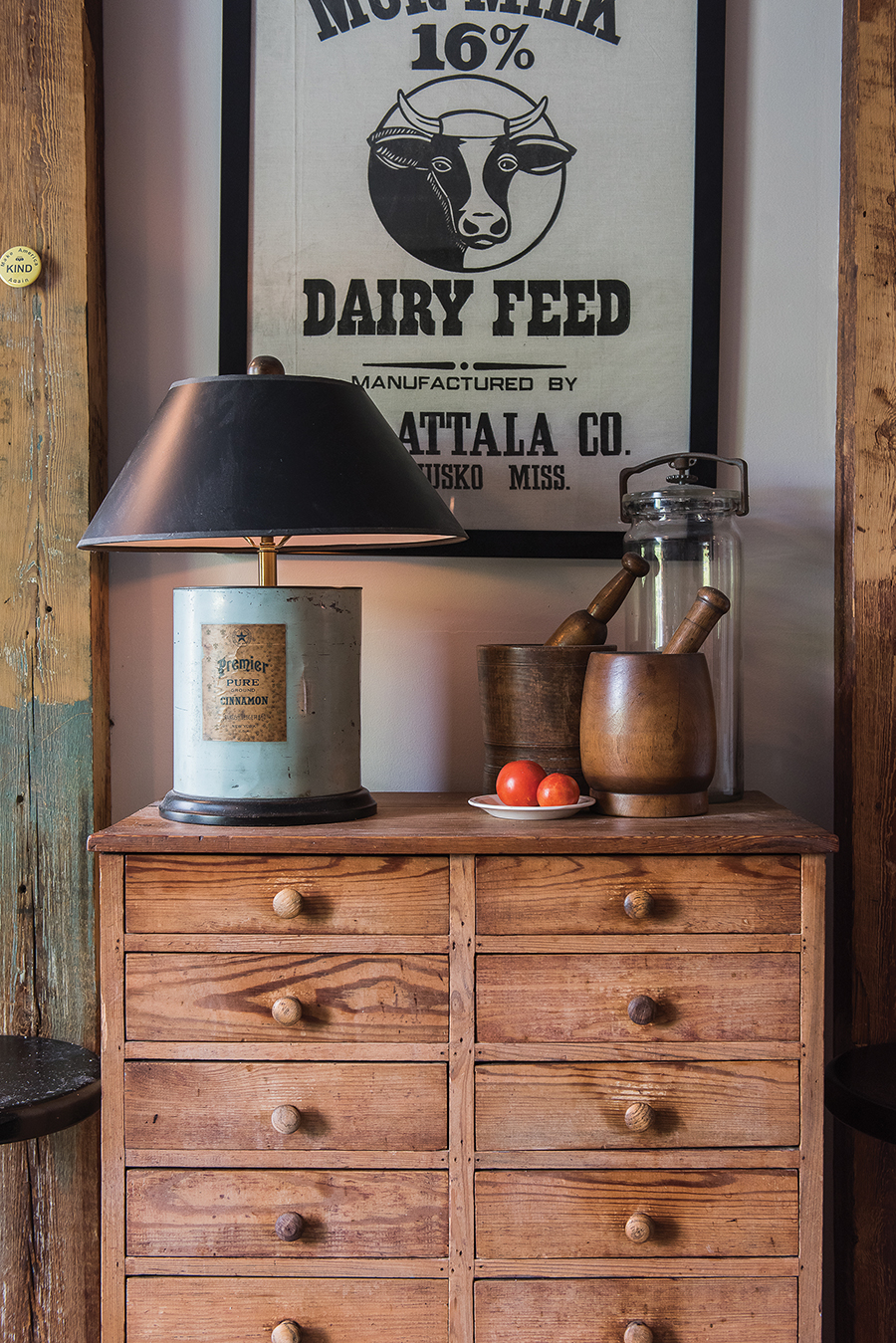

Also on display are a variety of mortars and pestles, “I’ve been collecting them for 25 or 30 years, one at a time. I don’t know why, I’m just infatuated with them.”

The pride of his collection is a windup fly swatter, an odd ornament from the Victorian age. “An antique dealer had it in his house,” Garrett explains. “I told him, ‘If you ever want to get rid of it I want to buy it.’ It would have been used in the middle of a table, with the same sort of mechanism that a clock would have. It supposedly keeps the flies away.”

In one corner there’s an antique writing desk while a rustic pie safe with perforated metal screens, manufactured around the time this place was built, hides a television and a collection of books. Everywhere you look there are bound volumes on just about every subject, many detailing the life and works of world renowned artists and photographers, about which the homeowner remarks, “Like Thomas Jefferson said, ‘I can not live without books.’”

“I was a design major in school,” Garrett says. “I ended up getting a degree in art education from UNCG. I did teach for a couple of years.” As an itinerate art teacher for the Greensboro Public Schools, he moved from one school to another. “I rotated with instructors who taught music and physical education for fourth, fitth and sixth graders,” Garrett recalls. Following that stint, he taught art at Mendenhall and Kiser junior high, but ultimately gave it up for the same reasons many in the profession leave: “I quit teaching because I got tired of filling out forms and lesson plans that no one ever looked at.”

A charming brick patio with a European flair awaits at the rear of the building. Beyond it is an English country garden populated with miniature shrubberies, stone pottery, a wispy Bonsai tree, with quirky accents that include a rusty, antique metal lamppost base.

The hearthstone from his grandfather’s fireplace has been repurposed for a bench that, Garrett recalls, ”Took four men and a couple of 12-packs to move.” A neat row of tall ginkgo trees, along with Japanese and Ming maples, shields any view of the train depot behind them. It’s a far cry from the mess that he inherited when he moved in, “Where we’re standing right now was trashed; you couldn’t even grow weeds back here.”

What could be more cosmopolitan than living above your store? Today a large portion of Garrett’s antique business, The Farmer’s Wife, is dedicated to flower arrangements, “I used to go to the farmers market and pick up a couple of bunches of flowers,” he explains. “I put them in the shop so as to not look so stuffy or stodgy.” When customers began to purchase them, “That mushroomed into people wanting me to do something with them for events or birthdays. It’s not something I was planning on happening, but now flowers are probably 65 percent of our business.”

Downtown Greensboro began roaring back to life in the 2000s. “I don’t know what started the resurgence of people wanting to come back to downtown,” Garrett reflects. “I think younger people are wanting the convenience where you can walk to businesses versus having to drive a car.” He found himself the beneficiary of a trend that few would have predicted back in 1994. “Next door they’re renting a man-cave for $1,200 a month . . . and it’s dark. In hindsight, this was probably the best business decision I ever made.”

The arduous journey that began with his hand being the last in the air at a sidewalk auction more than three decades ago has been completed, more or less. “It will always be a work in progress,” Garrett assures me. “But, as of June of this year, I paid off the mortgage. It’s finally mine.” OH

Billy Ingram first moved downtown in 1997, to the mystification of almost everyone who inevitably commented, “Why would you want to live there? There’s nothing but bums down there.”