Midway through her junior year at University of Maryland, where she was studying microbiology, Alexis Lavine decided to hang up her lab coat and pick up a paintbrush. Though she had long nurtured a dual interest in science and art — her father was a scientist and she had taken art classes from the time she was a child — she opted for the “lofty” ambition of becoming an artist. “Microbiology was practical,” Lavine says, “and I didn’t want to spend the rest of my life in a lab, surrounded by Petri dishes.” But a career in art? Most would deem it impractical . . . unless there were a way to combine the two. That’s exactly what Lavine did, by earning a Master’s in medical illustration from Johns Hopkins University.

Midway through her junior year at University of Maryland, where she was studying microbiology, Alexis Lavine decided to hang up her lab coat and pick up a paintbrush. Though she had long nurtured a dual interest in science and art — her father was a scientist and she had taken art classes from the time she was a child — she opted for the “lofty” ambition of becoming an artist. “Microbiology was practical,” Lavine says, “and I didn’t want to spend the rest of my life in a lab, surrounded by Petri dishes.” But a career in art? Most would deem it impractical . . . unless there were a way to combine the two. That’s exactly what Lavine did, by earning a Master’s in medical illustration from Johns Hopkins University.

In those days, the late 1970s, long before the digital revolution, medical illustration was done largely in pen and ink, and occasionally watercolor. “It’s clean and it dries fast,” Lavine explains. Her profession nurtured her talent in the “unforgiving” medium, and, she adds, “it taught me how to draw, and draw anatomical forms. (She typically begins a painting by sketching it out first.) Medical illustration also called for artists to work on-site — a disadvantage when Lavine’s husband, Phil, was transferred to the small town of Cumberland in the western part of Maryland. Nonetheless, it was a beautiful place, “like Boone without App State,” as Lavine describes the burg set in the Appalachian Mountains, conducive to raising children . . . and painting en plein air — a technique of painting outdoors that became popular in the 19th century and preceded Impressionism. For the next several years, Lavine applied her artistic talent and training to mountain landscapes, forests, rolling rivers, learning how to paint fast, so as to capture the sun’s light as it moves across the sky. “Plein air forces you to decide quickly and make decisions with confidence,” Lavine says. And indeed, you can see her strokes, both bold and splashy, and precise, capturing light shimmering on the surface of a lake, or filtering through the branches of trees.

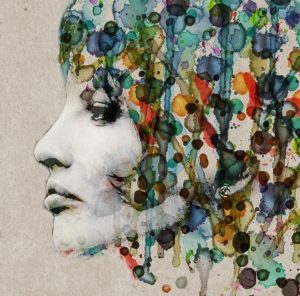

After she and her husband moved to Greensboro in 2002, Lavine continued to paint outdoor subjects — waterfalls at the Bog Garden, a stone bridge in Fisher Park — until about 10 years ago, when she decided to shift her focus to studio work. One of her goals was to get into exhibitions. “I needed to be in the studio to take time to make it my absolute best,” she says of her art. She knew that studio time would force her to “slow my brush down and think a lot more about what I wanted to say in a painting.” A trip to India gave her an unexpected nudge, when she noticed the hand gestures among a group of women clad in colorful saris, their arms adorned with gold bangle bracelets. Rendering just their arms and hands in a painting she titled Sisters, Lavine says, “It was a turning point for me.”

A 180-degree turning point, as it turns out, for the artist started painting figures. Photographing people when she’s out and about — a long-haired bearded fellow at a jazz festival, a couple eating on a boardwalk, baseball fans enjoying a Grasshoppers game — depicting in precise detail the small moments of what it means to be alive: the joy of hearing music, of tucking into a good meal, the boredom of waiting, the tenderness of a touch, the wonderment in observing the natural world.

Lavine’s new artistic direction has helped her reach her goal of gaining much-deserved attention. She exhibits her work at The Art Shop, at Hampton House Gallery and Blissful Studios and Gallery in Winston Salem, and from May 3–29, a solo show of her paintings, All Watercolor II, will appear at The Artery Gallery on Spring Garden Street. Her summery nod to Grasshoppers season, Toppa the Eighth, will travel to Qingdao, China as a part of a joint exhibition between the Missouri Watercolor Society and the Qingdao Laoshan Museum. Meanwhile, as a member of myriad watercolor societies and associations, Lavine teaches classes, sometimes in far-away locales, such as Charleston, S.C., and two days a week at her home studio in northwest Greensboro. She is excited about a newly installed overhead camera that helps her students observe her more closely as she deftly dabs her brush into a pallet and creates a scene — be it a windowsill on a quiet morning or a wry still life of Chinese takeout. Otherwise, she’ll be out in public, observing the flow of humanity, awaiting the next muse to fire her imagination. “I started painting people from the inside out,” Lavine reflects. “Ten years ago, I started painting people from the outside in.”

Info: alexislavineartist.com; arterygallery.com. OH

Nancy Oakley is the senior editor of O.Henry.