Yellow Fever

Or, walking a mile in someone else’s shoes

By Cynthia Adams

I deviate from the Interstate, in search of relief from endless roads with nothing to offer but exits.

The town of Benson, with a namesake fruitcake that I, alone, apart from my mother, eat with gluttony, is a small town easily digested. A hint of quaintness; but mostly used car lots and fast food joints, and soon in my rearview mirror.

Tobacco fields, leaves curling yellow, stretch beside the road that leads to Wilmington. Then, a sign: Spivey’s Corner. My Honda slows. Where is the store? The store near a sign promoting the annual hollering contest?

But it isn’t hollering that I remember; I remember a summer day in 1980. And an incident that scared me to the soles of a new pair of platforms.

We were jammed into an Oldsmobile wagon, a white Yank tank always thirsting for gas, returning from Wilmington. Our boss, the wheelman, swung into the country store. Two of us tumbled from the car. Our boss pumped as Jim and I took requests, then entered the store swatting at the heat.

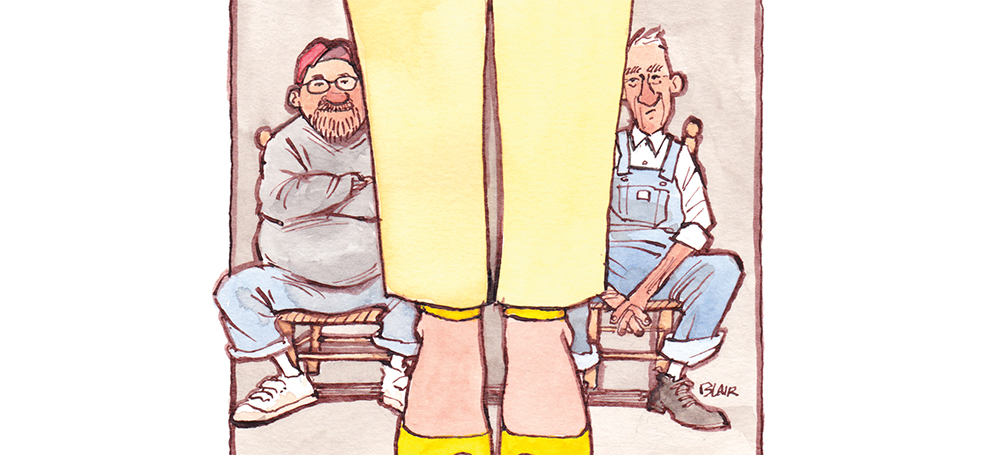

The store was instantly familiar. Farmers gathered in places like this, escaping the endless demands of lands that gobbled all their time. They cupped salted peanuts into the throats of a cold Pepsi and debated the merits of seed and feed, and all the million ways that a farmer’s profits were nibbled to nothing.

My father owned farmland. These were my people. And yet . . . the place fell unnaturally quiet.

Jim, his dark skin in high contrast to his starched white shirt, moved soundlessly. As a throat cleared, he disappeared behind a rack of Wise potato chips. My heart began thrumming. I wore a decent pantsuit, the one chosen earlier for a breakfast meeting. My shoes, however, were an indulgence. New, impractical, jonquil yellow platforms.

The clerk at the counter stared, eyes never leaving me. I snatched up Nabs and fished bottles from the drink chest, placing them onto the counter with a ten. Our eyes met. Hers glared. I slid mine away, around the store; Jim was still somewhere behind the chips. Apparently, black men were an uncommon sight in Spivey’s Corner. A sight that was attracting uncomfortable attention.

“I just got one question,” she muttered, breaking a pin-drop silence. She of an undeterminable age; maybe 30, maybe 50, with graying worn teeth. I mustered one syllable, dropping my eyes to Alexander Hamilton, and smelling trouble more potent than her sour smell.

“Yes?” The store door slammed shut.

“Hurry, Jim,” I whispered to myself, and stared down again as if I had borrowed my feet for a test walk.

“Whar’d you get them shoes?”

I did not breathe. A frisson ran through me to the waffle soles.

“Prago-Guyes,” I answered. The wonderful Greensboro shop was where all my spare money flowed.

“Aw,” she answered, pushing my change across the counter. Change I pocketed without counting as I hurried out on the waffle soles to the Olds, gassed and ready, with Jim waiting, his breathing shallow.

We pulled away with Spivey’s Corner, home of the hollering contest, still much closer than it appeared in the rear view mirror. OH

Cynthia Adams is a contributing editor to O.Henry based in Greensboro. Her dear colleagues Jim Isler and David Atwood are long gone, as is Prago-Guyes.