Mama Patty’s Scar

And the perfection of a soul

By Cynthia Adams

It’s there.

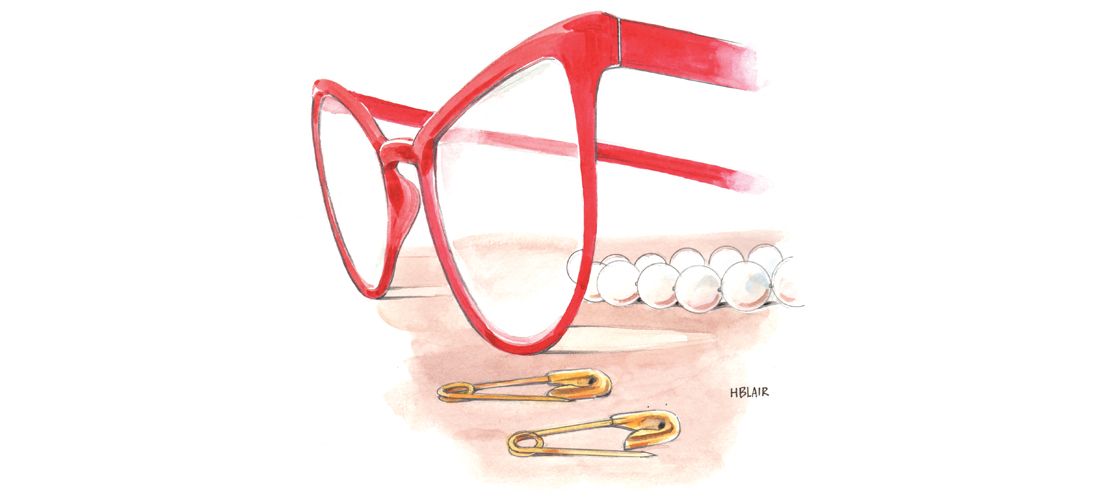

Right where Mama Patty’s soft pink nightgown flares slightly open at the armhole. I stare furtively at the depression, the angry network of scars, as she reads, cat-eye reading glasses in place, blue-black curls propped against a lace-edged pillow. She’s gripped by one of her Zane Grey novels.

Beneath the gown she wears a white cotton bra. A form pinned into the left empty cup is held by two gold safety pins. At age 6, I am dying to ask her about this, but something stops me. She says I ask too many questions, which vexes her.

Questions about my grandfather, Lewis Clive Tucker, and their baby Roy vex her, too. Both dead.

My friend Tony died when he ran in front of an Oldsmobile. Baby Roy died, too, writhing on the kitchen table. Spinal meningitis, misdiagnosed.

Mama Patty walked outside, frantic for the doctor’s arrival, and had a vision of a small white coffin.

Little Roy was buried in such a coffin, the color of pearls.

Yet she lies beside me, reading her western like nothing in the world is wrong apart from the worry that I might interrupt with another question.

Until she reaches up and turns the knob on the bed light, I watch that angry pink place on her left side until it becomes my scar, too.

The sheets smell of the sun. The Martha Washington bedspread is carefully folded. The mourning dove sings its mournful song. This all fills my head, imprinting something in me in the darkest of darkness.

Mama Patty breathes deeply. I try to sleep, thinking of the morning to come, dreading that she may want to fish. Snapping turtles and water moccasins sometimes appear at the wild old pond. The fish, once hooked, wrenches and arcs until it is placed, flapping, into the tin bucket. When she cuts off its head and strips out its guts, the gore splashes onto her apron.

The next day, although I do not know this as I drift to sleep, she will fill a large washtub and let me splash to my heart’s content.

Mama Patty will give me a baloney-and-mustard sandwich to eat, and take me to check the rabbit boxes. We will walk to the mailbox, wearing red flip-flops and sucking the juice from a honeysuckle.

The questions that come in daylight are easier than questions that come in darkness. I do not think of the scar all day, forgetting completely that a part of her has already been cut away.

Her beloved Pearl Grey Zane (Pearl was his first name) was a sensation in his time. He was untamed. He feared man would destroy all that was untamed in the natural world.

I need this wild life, this freedom, he wrote.

The next night, as Mama Patty turns a page and the gown gapes again, it is impossible to look away from the depression where a breast should be.

I do not want them to cut one more thing away. Mama Patty is just right as she is. Perhaps perfect. OH

Cindy Adams is a contributing editor of O.Henry.