O.Henry Essay Contest Winners

The Year That Changed Everything

Last fall, we asked our readers to submit essays under 1,000 words that captured a year that changed the course of their lives. Our inbox was pleasantly stuffed with heartfelt stories from our community. There were stories of loss and grief, war, and devastating diagnoses. And there were tales of triumphing over cancer, adopting new pets, holding the winning tickets and attending first concerts — featuring no less than the Beatles!

Every single entry made us feel something. We laughed, we grieved, we cried right along with our essayists. And then we cried again when we had to choose just three from such a stellar collection.

To all who entered, thank you. We do not take for granted that you shared your stories bravely — and so eloquently — with us. And to all who didn’t enter, we’ll be looking forward to reading your story next time. And finally, to our winners, congratulations!

—O.Henry editorial team

First Place

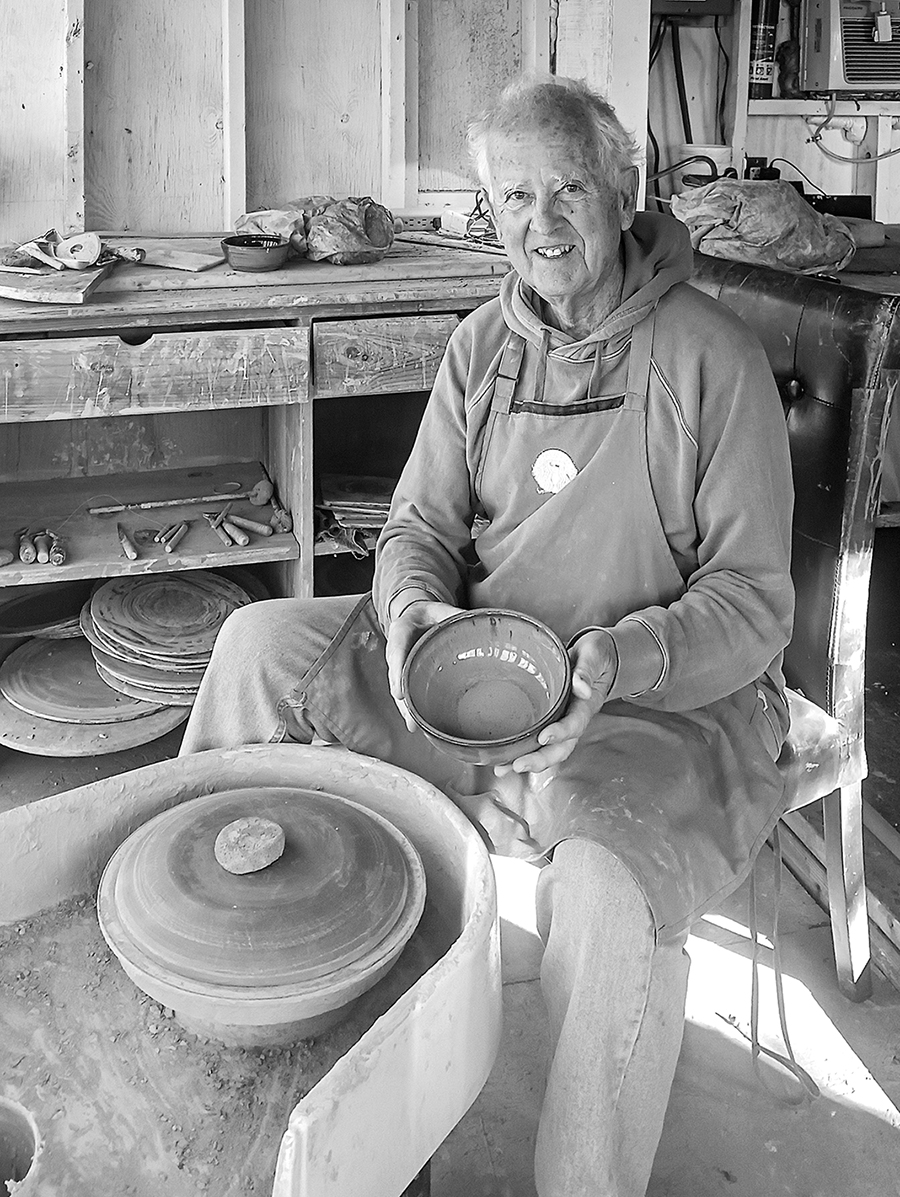

Now What Are You Going to Do With Your Hands?

By McCabe Coolidge

Our hands cupped around glasses of red wine, a candle flickers, almost in cadence with our short spurts of words. We sit, bereft, until the pause becomes pregnant with another offering. My friend, Susan, looks at me, right above the candle flame and says, “Now, what are you going to do with your hands?”

I glance at my wife, Cathy, still focused on her glass of wine, empty? Needs filling, maybe she isn’t listening. She drifts away. Often.

I stare at Susan, a frown on my face, waiting to hear more words. “What ever does she mean?” I wonder. “Hands?”

Through the evening we have been listening to Leonard Cohen. Especially “Suzanne,” these long, lonely days I am in free fall, “Suzanne takes you down.” I get it. In that moment, the three of us begin weeping. That question going way below the surface of our lives, spiraling down.

Robin is seated on the side of her hospital bed. Her left arm has an IV attached to it; her feet are stretched out. A man sitting on a stool is leaning down and painting her toenails. Robin giggles. “Wait a minute,” I say to myself. “It’s Charlie Schafer, her pediatrician.” His hands gently, slowly paint each toenail. It’s October 27, Robin’s birthday. She has been admitted to UNC Hospital and we have just been told that tomorrow we should take Robin home. “Nothing more we can do for her here; take her home and just love her,” the attending physician speaks low, glancing to his right, then left, like he wants to be somewhere else.

We clung to an elusive hope. Robin was diagnosed with cystic fibrosis when she was 2. We were taught to do a light, steady “tapping” — three and often four times a day — percussive-like, with cupped hands on each lobe of her lungs. We named it, “time for tat.”

We were told this would keep her alive. Longer. The goal of “tat” was to loosen up the phlegm in her lungs so she would cough and cough, staving off pneumonia. Coughing hurt Robin and she resisted and tried to hide a cough. A double bind for us. Tapping on the lobes of her lungs hurt her and yet, to keep her alive, we had to hurt her.

On Christmas Day we stopped tat. Her mother and I looked at each other and we stood there, quiet, allowing Robin to sleep in.

In the midst of the celebration of the United States Bicentennial Year early in the morning of Martin Luther King Day, Robin woke us up at 5 a.m. I picked her up and checked her fingers, blue. Her breathing slow, faint. I went to her mother, “Better come into Robin’s room.” We held her, smothered her with kisses and prayed that her journey home would be without pain.

Susan takes another sip of her wine and asks again: “So what are you going to do with your hands?” She pauses, holds the wine glass in both hands: “I have signed up for a pottery class, a week after Easter. At Meredith. 6–8 p.m., Thursdays. I want you to come with me.”

In my mind I am reviewing my life: “B.A. in economics. M.B.A. in marketing, an advanced degree in theology and she wants me to sign up for an art class!”

Thursday night. There is a porch. Four kilns. Susan and I walk into the white cottage. A shaggy guy, tall and bulky with a winsome smile on his face speaks: “Welcome, I’m John. John Givens. This is a beginning pottery class. Take a seat at the wheel, any wheel.”

What do you do when your child dies in your arms? When you have been helpless in stopping the pain? Emptied out of any hope and meaning? An avid reader of poetry, Mary Oliver continues to ask of me, “What are you going to do with your one wild and precious life?”

Sitting at that wheel, wedging that clay. Mesmerized by the turning of the wheel, the mystery of form emerging from a chunk of earth. When sorrow overwhelmed and sadness took me way down, Thursday nights arrived with a little Stan Getz and his saxophone in the background. I would tie my apron. Sit down, cup my hands, and the journey into the unknown would begin.

What was I going to do with my one wild and precious life, when I couldn’t keep alive a life, so precious, that was given to me? Wander. Pay attention to longings and yearnings. So I did. Bought an abandoned farm on a river, down a long gravel road, an hour from Chapel Hill.

Many years later, I took dance classes at Harvard, separated from my wife, moved onto a sailboat in San Francisco Bay. Started up a big rambling home for HIV folks in Asheville with my beloved. Still through all this grief and searching, I kept my hands in clay.

It’s the first weekend in December and I am sitting on a stool in the parking lot of High Point Library. It’s a craft fair for those wanting handmade art for Christmas presents. Although a bit nippy, I am wedging clay, throwing it down on the wheel to begin centering and pulling up. A family of five is watching me, the two youngest children held by the mother. The older one and the father are intent on the movement of my palm and fingers . . . a cup slowly emerges.

The dad looks at me as I take a short break to breathe a little more deeply and to inspect how this pot is coming along. He asks, “I love watching your hands and what you can do on that wheel, how did you get into pottery? What got you going?” OH

McCabe Coolidge wants to live fully with these passions: surrounded by love from his sweetheart and three daughters; and with his hands in clay, pen on paper, paddle in water, feet celebrating Tracy Chapman singing “Give Me One Reason” and Leonard Cohen singing “Suzanne.”

Second Place

A Friendship That Changed Everything

By Sarah Ross Thompson

It all started in 1995 with an Alanis Morissette cassette tape and a few outdated dELiA*s catalogs. We were two seventh grade girls in a small, Bible Belt town dreaming of becoming writers and finding cute boys who really “understood” us. The year that changed everything was the year I found a true friend.

Not to harp on a truth that any feeling human already knows, but middle school is vicious. While I was figuring out what parts of the world felt authentic to me, I also experienced rejection for many of those very same things, and, in the beginning, I found it to be a lonely time.

So, I don’t remember exactly how it happened, but I think it involved a homeroom class turned free-for-all where there were too many kids and not enough teachers to maintain any sort of order. A cassette tape was passed from her to me, and, looking back, it was quite a generous offering because I did not provide one thing in return. I took it home for a week and memorized every single word. In fact, I’m pretty sure I damaged the tape by rewinding it so many times to get the lyrics just right. Afterwards, I felt changed. Enlightened. “Jagged Little Pill:” my first experience with music as a religious experience. All made possible by a girl from homeroom.

The simple fact that we both loved the album made me feel as if she and I were kindred spirits, and, to this day I still think music is one of the best ways to find your people. But, mainly, that she had shared one of her prized possessions with me so freely and easily made me know that she was kind. And it truly meant the world. Her name was Shenell, by the way.

After that we were inseparable. We browsed through dELiA*s catalogs, of course never buying anything, and she didn’t pass judgment on my pre-internet, mostly failed attempts at ’90s grunge. We compared notes on boys. Often. To this day, the middle schooler that lives on in me prevents the naming of our two main crushes here, but they likely know who they are.

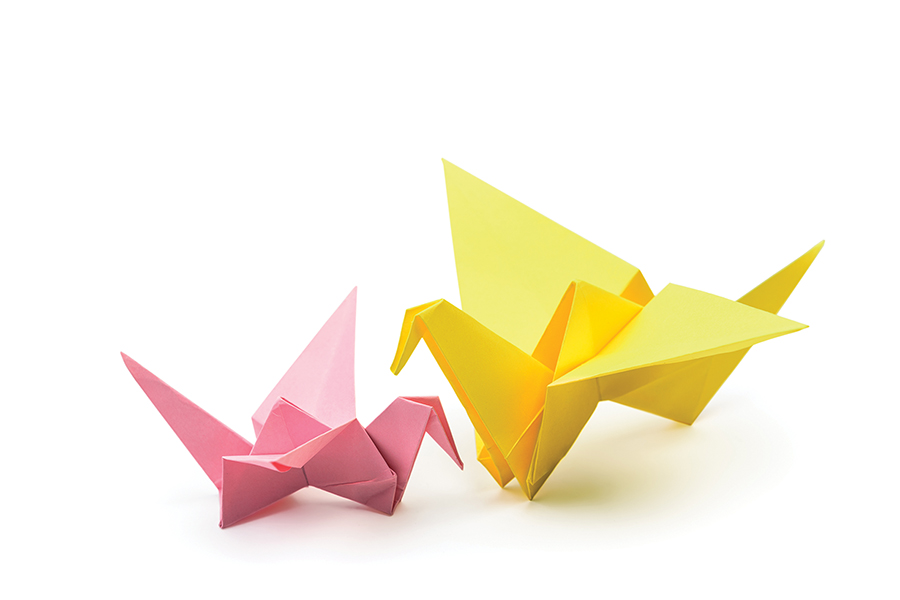

We found that we shared a love for writing. In fact, we thought of ourselves, not so modestly, as “up-and-coming” literary voices. We kept a shared journal that got passed back and forth between classes, and we made up new words that we used in day-to-day conversation (“Manistified” was one we were especially proud of). We discussed books that would shape us for the rest of our lives. We cried when Asher escaped with baby Gabe in The Giver and stood wide-eyed and heartbroken on our class trip to the Holocaust museum after reading The Diary of Anne Frank. We wrote poems, mastered origami-style note folding and scripted very detailed messages in each other’s yearbooks in which we referred to each other as “Soul Sisters.”

And while the brutal, confusing and miserable parts of middle school still happened, I was not alone. At such a young age, I experienced the pure joy of being known, and it changed everything.

Almost 30 years have passed since that seventh grade year, and we have inevitably grown apart and back together and apart again. While too much time passes, sometimes years, between visits, I’m happy to say that my first true friend remains a part of my life. Shenell was by my side when I married a boy who actually does understand me, and a few years later we both cried when her beautiful, literary daughter read a book to my baby boy. And while I would never dream of calling myself a writer, I knew that one of my first fumbling attempts at putting my heart on paper had to be a tribute to her. OH

Sarah Ross Thompson lives in Greensboro with her husband, John, and two children, Owen and Ellie. A psychologist by training, she finds getting lost in the woods and writing short stories to be two of the greatest therapies.

Third Place

You Know I Feel Alright

By Christine Garton

Fifth grade was shaping up to be a good year for me in Elkin, my cozy North Carolina foothills hometown. I was earning an impressive array of Girl Scout merit badges and had learned to ride a unicycle after school at the YMCA. Our Methodist youth handbell choir had mastered “Fairest Lord Jesus,” set to debut at Easter service. Best of all, I was president of my Beatles fan club.

We preteens expended enormous amounts of energy dancing to Beatles records, swooning over magazine photos and collecting Beatles bubblegum cards. Seeing the movie A Hard Day’s Night, elevated our Beatlemania to a new level, and my handheld transistor radio accompanied me everywhere. On rotation, club members phoned the local radio station before leaving for school to request that the DJ play a specific Beatles’ tune precisely at 10:10 a.m. during morning recess. I’d flick the radio on, and, if the DJ complied, our day was made.

When my parents gave my sisters and me the news in early spring of 1965, I cried: We were moving because Daddy had taken a new job in Chicago. My two sisters were young enough that they didn’t fully grasp the ramifications of this turn of events, but, for me, it was earth-shattering. Elkin was all I had known since the age of 4, and I would essentially be leaving behind a lifetime.

Once school let out for the summer, we made preparations to leave 188 Edgewood Drive. I packed up my books, dolls, record player and Beatles collection, then made the heartbreaking drive with Daddy to take my beloved beagle, Hazel, to a farm out in the country. After the movers finished and we bade the neighbors farewell, the five of us crammed into our little black Peugeot and headed north.

Our new home was a townhouse in a suburban neighborhood of townhouses whose residents were almost exclusively young marrieds with little ones. As soon as they saw me, the Swardenskis next door lit up as they considered the prospect of my babysitting their infant, toddler and preschooler. I experienced a similar reception from other parents in adjacent buildings, and thus began a miserable summer in the company of small children.

Most mornings were spent entertaining the aforementioned trio of siblings in their wading pool, where they splashed in water that, by lunchtime, had turned oddly yellowish. Afternoons, I took the 3-year-old across the way to the park so her mother could sunbathe, reclining behind sunglasses while balancing a large tumbler of ice water on the arm of her lounger – or I assumed it was ice water until I noticed the olives at the bottom of the glass. Evenings were first come, first served for whichever desperate couple snagged me to play ringmaster to their hyperactive youngsters while they celebrated a night on the town.

At 25 cents an hour, I was flush with cash and made weekly bicycle trips to town to spend my earnings on Teen World magazines and an ever-growing stack of Beatles 45s. My parents, to their credit, were determined to take advantage of all Chicago had to offer, so we visited museums, went to the Brookfield Zoo, and swam in Lake Michigan. Our family joined a church, but Sunday school classes were a bust in terms of making friends. My clothes were all wrong, and my Southern accent provided a convenient target for endless snide jokes.

I moped in my bedroom nights when I wasn’t babysitting, penning sad letters to faraway friends and listening to my radio in hopes I would fall asleep as Paul McCartney crooned a tender ballad into my ear. Dozing off to WLS Chicago late one night, I was jolted awake by the DJ’s announcement that the Beatles’ upcoming U.S. concert tour would bring them to the Windy City in August. The next morning, I flew downstairs to breakfast, armed with this new revelation. I begged. I pleaded. My parents said they’d think about it. Then Daddy left for work. Waiting all day for him to come home was excruciating, but, yes, he would take me to the concert on one condition — no screaming.

Sears, Roebuck and Company sold the tickets, which were purchased for $2.50 each and dated 3 p.m., August 20, at Chicago White Sox Comiskey Park. I counted the days until the afternoon of the performance arrived at last, and we entered the stadium along with 25,000 other fans to take our seats high above the field, the atmosphere crackling with excitement. The opening act, Cannibal and the Headhunters, was received politely, but when a stream of blue-shirted policemen emerged from the dugouts and encircled the stands, the crowd exploded.

Paul, then Ringo, George, and finally John, in his black newsboy cap, strode across the infield to the raised stage constructed over second base. Amidst deafening screams, the Beatles kicked off with a rousing “Twist and Shout.” I kept my end of the bargain as promised, though it was hard to hold back. Each successive number from the playlist stoked the crowd’s delirium to the point one could barely hear the music. Daddy tried unsuccessfully to shush the teenagers shrieking all around us, but I was transfixed. It was a dream I did not want to wake up from, and the cloud of misery that had been my summer floated away.

On stage there was a pause, a conversation among the Liverpool lads, heads together as though they were making a decision. The crowd quieted. George nodded to John and Paul, who resumed their positions, and then . . . twaaang . . . the unmistakable opening chord of “A Hard Day’s Night” split the air, and 25,000 fans went wild. Climbing upon my seat to see past the flailing bodies in front of me, I sang along with all my heart: “You know I feel alright . . . You know I feel alright . . .”

And in the magic of that moment, I did. OH

Christine Garton is a closet humorist who resides in Greensboro with her infinitely patient husband, Ken. She currently works as a staff writer for Advancement Communications at UNCG.