The Soong Saga

North Carolina’s link to the fall of “The Last Emperor”

By D.G. Martin

One of North Carolina’s most interesting stories takes us back to the 1880s when a young Chinese boy winds up in Wilmington, where he converts to Christianity and then returns to China as a missionary. He becomes wealthy, and his family becomes extremely powerful. How it all happened is a saga that is almost unbelievable.

In Wilmington there is a small granite monument on the grounds of the modest, lovely Fifth Avenue Methodist Church building. It reads: “Charlie Jones Soong, father of the famous Soong family of modern China, was converted to Christianity in the old Fifth Street Methodist Church, which stood on this site. He was baptized on Nov. 7, 1880, by the Rev. T. Page Ricaud, then pastor. One of his six children, Madam Chiang Kai-shek, whose Christian influence is world-wide, is the wife of China’s devout generalissimo and president. Erected in 1944.”

Here is the report from the November 7, 1880, Wilmington Star announcing an event that would ultimately have a profound impact on modern Chinese history: “Fifth Street Methodist Church: This morning the ordinance of Baptism will be administered at this church. A Chinese convert will be one of the subjects of the solemn right (sic), being probably the first ‘Celestial’ that has ever submitted to the ordinance of Baptism in North Carolina. The pastor, Rev. T. Page Ricaud, will officiate.”

That Celestial, as some Americans then referred to a Chinese person, was Charlie Soong, a teenager, whose North Carolina Methodist sponsors arranged for his education and subsequent return to China as a missionary.

A minister in Wilmington persuaded Durham tobacco and textile manufacturer Julian Carr to take an interest in Soong. Carr brought Soong to Durham and then arranged for him to enroll as the first foreign student at Trinity College in Randolph County.

Carr and Soong developed a “father-son” lifelong friendship, despite Charlie Soong’s serious flirtation with Carr’s niece, which resulted in Charlie’s exile to Vanderbilt University for more religious training. After being ordained as a Methodist minister, Soong went back to China as a missionary. Once there he drifted into business, developing the Bible printing operation that became a springboard to greater financial success, often with Carr’s backing.

When much of China’s limited manufacturing capacity was under the control of foreigners, Soong showed that the Chinese could do it for themselves. He helped construct a platform on which China’s modern manufacturing base is built. He printed Chinese Bibles so inexpensively that they drove the competition — mostly Europeans — out of business and, in the process, became one of the country’s wealthiest and most powerful business and political insiders.

It was the last days of the Qing Dynasty and “The Last Emperor,” and China was in revolutionary turmoil. Soong helped fund the activities of the major revolutionary leader, Sun Yat-sen, sometimes called the “founder of the Chinese Republic.”

Soong sent most of his children to the United States for education. When his three daughters came back to China, they married prominent Chinese. One daughter, Ching-ling, married Sun Yat-sen and, as Madame Sun Yat-sen, remained an important figure in Chinese government long after her husband’s death. She even served under Mao Zedong as a vice-chairman of the People’s Republic from 1949 to 1975.

The oldest daughter, Ai-ling, married banker H.H. Kung, who became finance minister in the Nationalist government.

Another daughter, May-ling, married Chiang Kai-shek, who led the Nationalist government until he was driven to Taiwan by Mao’s forces in 1949. Madame Chiang Kai-shek was well known to Americans and a favorite of many until her death in 2003 at the age of 105.

One son, T.V. Soong, represented China at the founding of the United Nations in San Francisco in 1945. After the Communist takeover of China, he moved to the U.S. and became a highly successful banker.

The Soong family was so important in China that it is sometimes referred to as The Soong Dynasty, the title of the most popular and detailed version of this story, written by Sterling Seagrave and published in 1985. It presented an unfriendly version of the family history, but a review in The New York Times saw it differently. “Indeed the charm of the man often outshines Mr. Seagrave’s attempts both to debunk him and make him sinister,” said the Times.

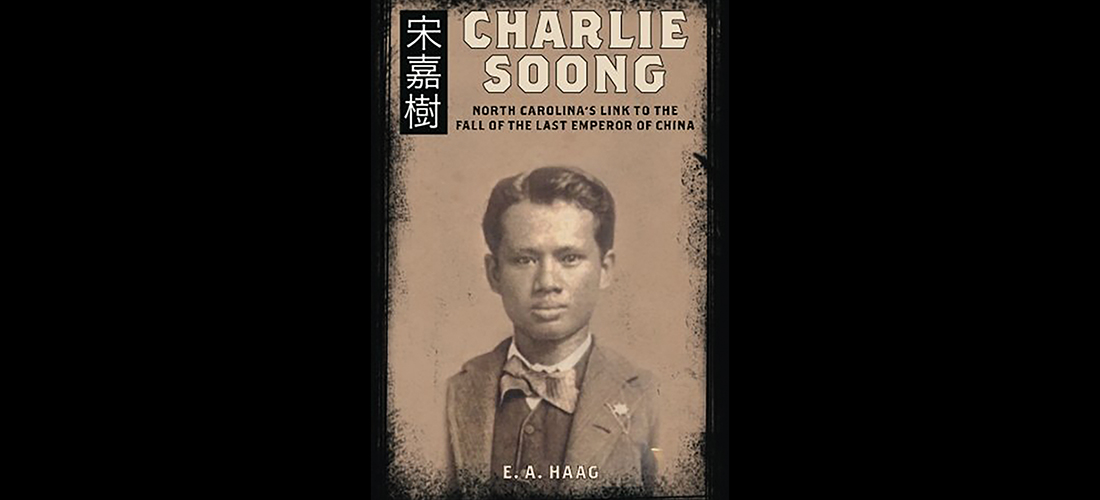

A more recent book by former Greensboro resident Ed Haag, Charlie Soong: North Carolina’s Link to the Fall of the Last Emperor of China, gives us a more balanced account. Although the Charlie Soong story is not new, Haag dug up previously unpublished material, much of it from the Soong papers housed at the Duke University library. Haag explains better than earlier authors how Charlie Soong became so wealthy. While others have written about Soong’s missionary work leading to a business printing Bibles, his association with a flour mill in Shanghai also contributed to his success. According to Haag, Soong’s greatest wealth came from his role as a “comprador,” a fixer and go-between who helped bridge the different customs and expectations of Western suppliers and traders and their Chinese counterparts. Those North Carolinians who already know about Charlie Soong will appreciate Haag’s refinements and additions. For those who never heard of Soong, Haag’s book is a great starting point.

But the Soong family’s connection to North Carolina doesn’t end there.

On Aug. 30, 2015, his great-grandson Michael Feng came to Wilmington to be baptized in the same church where his great-grandfather received the sacrament. Feng and his wife, Winnie, are longtime active participants at The Episcopal Church of the Heavenly Rest, a historic church in New York City, at Fifth Avenue and 90th Street.

“It was the church of my grandfather, T.V. Soong, where Winnie and I were married and raised our two children,” said Feng. “I had just never gotten around to being baptized. I guess my parents were too busy when I was young. Winnie had been after me for a long time to be baptized. And when we were planning a trip to North Carolina for a wedding, we decided this would be a wonderful time and place for my baptism.”

Feng explained to the congregation at Fifth Avenue Church that his family remained grateful to the North Carolinians who provided his great-grandfather the educational, spiritual and financial resources that made the difference for Charlie Soong. “He gave these resources to his children and our family,” said Feng of a Chinese dynasty announced in a note in the Wilmington Star 135 years before.

Almost seven years after his baptism in Wilmington, Michael and Winnie Feng remain active at the Church of Heavenly Rest, where there is another North Carolina connection. The leader of that church is its rector, the Rev. Matthew Heyd, who grew up in Charlotte and was a Morehead Scholar and student body president at UNC-Chapel Hill.

Surely, Charlie Soong would be pleased. OH

D.G. Martin hosts North Carolina Bookwatch Sunday at 3:30 p.m. and Tuesday at 5 p.m. on UNC-TV.

His favorite book growing up was Lou Gehrig, Boy of The Sand Lots by Guernsey Van Riper Jr.