Hell of a Read

A dizzying journey of the imagination

By Anne Blythe

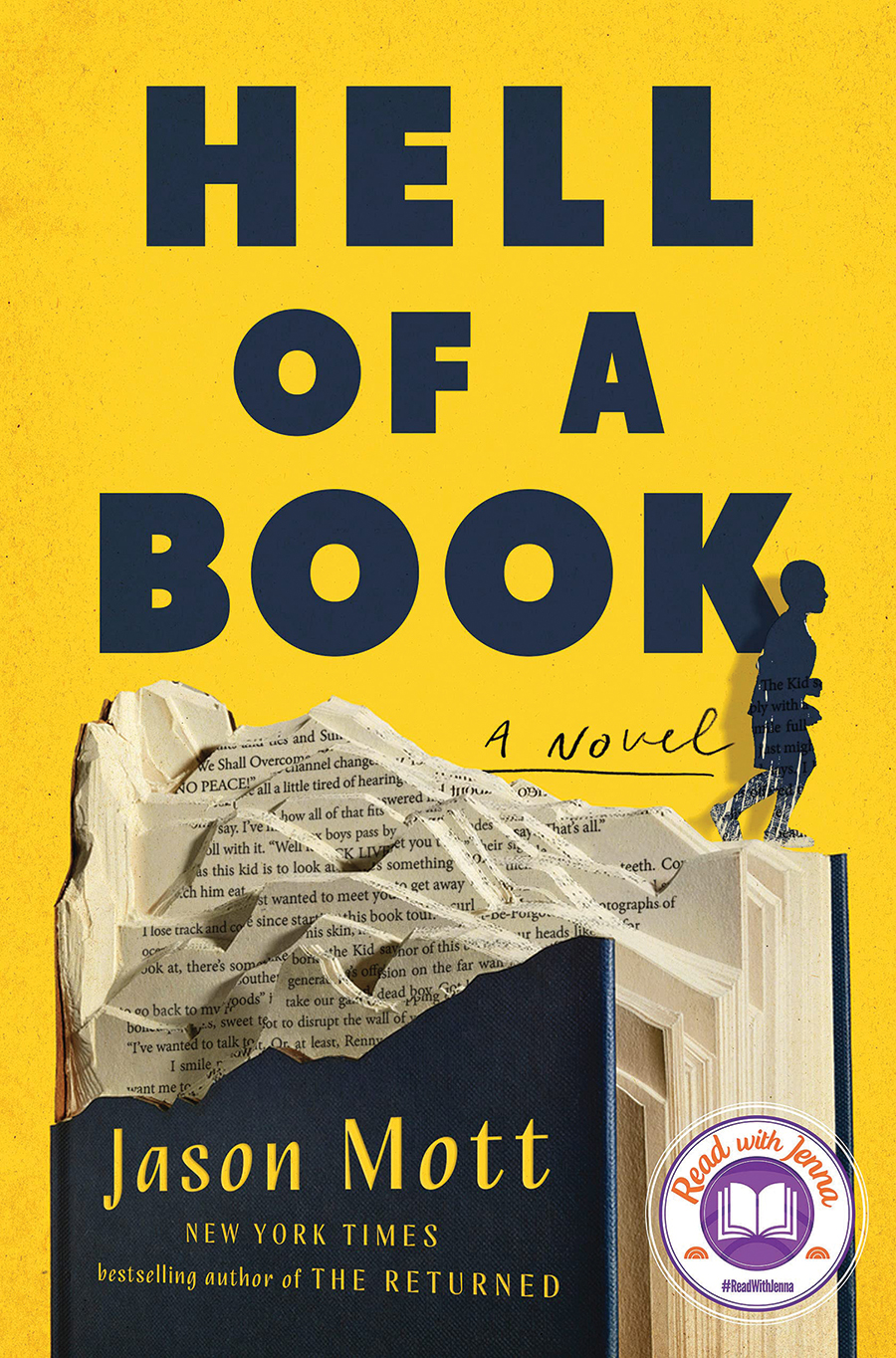

The adage that you can’t judge a book by its cover is not one that works for the fourth novel written by Jason Mott, a writer and poet who lives in southeastern North Carolina. The title of Mott’s latest work of fiction, Hell of a Book, is in large, bold capital letters at the top of a black and yellow cover. Go ahead, judge it.

It is a hell of a book, one that explores racism, police violence and being Black in America.

It’s a novel — and a mystery, too — about a novelist with a vivid imagination. It’s difficult to know what’s real and what the writer is imagining. It’s also challenging to see how the main characters are connected, until the very end. Even then, there’s no certainty as to whether they’re truly bound in anything other than the novelist’s mind.

Mott pulls readers through a difficult and sometimes overwhelming conversation about “The Altogether Factual, Wholly Bona Fide Story of a Big Dreams, Hard Luck, American-Made Mad Kid” — his subtitle — with madcap humor, painfully poignant prose and a show-me-don’t-tell-me contemplative style.

The protagonist is a Black fiction writer on a dizzying book promotion tour, an unnamed bestselling writer who is whisked through a blur of airports, hotels and cities by a quirky cast of drivers, and a profit-driven agent.

We first meet him at 3 a.m. in the hallway of a Midwestern hotel, where he’s naked, locked out of his room and being chased by an angry husband who has caught the author with his wife. He runs after him, flailing at him with a large coat hanger.

As the protagonist is about to be caught, the elevator doors open, and he escapes into a new scene with his savior of the moment, an elderly woman bringing home groceries in the wee hours of the morning.

As the naked novelist and woman watch the hotel floors counted off in the elevator, Mott introduces readers to a sobering reality that becomes a central theme as the writer moves through his chaotic, alcohol-infused tour. Another Black male has been shot and killed by police, but Mott doesn’t give him a name. The old woman asks the novelist a question:

“Did you hear about that boy?”

“Which boy?”

“The one on TV.” She shakes her head and her blue hair sways gently like the hair of some sea nymph who’s seen the tides rise and fall one too many times. “Terrible, terrible.”

The novelist tries initially to go on with his celebrity life without fleshing out his feelings about “the boy.” He tries to push the latest outrage blaring on TVs and pulling Black Lives Matter advocates into the streets with signs and chants into that place deep inside himself where injustices stew without boiling over.

This time, though, the world is outraged, and the protagonist can’t tune out the calls to stop the madness or the cries to confront centuries of oppression and brutality.

The morning after the naked ride in the elevator, we meet The Kid, a mysterious but thought-provoking boy who might, or might not, be a figment of the author’s imagination. He looks to be about 10 years old, “impossibly dark-skinned,” and might, or might not, represent the all too many Black children lost to police violence.

We also get to know Soot, another Black boy in rural North Carolina, whose father tries to teach the power of invisibility, picking up on a theme in Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man about not wanting to be seen by oppressors. We’re left to wonder how these boys are connected to the protagonist.

Early on, it becomes clear that the touring novelist has what he describes as “a condition,” an unnamed affliction through which he can blend an imaginary world with reality. His storytelling style, almost a stream of consciousness, can be disorienting but riveting, mind-numbing but thought-provoking.

On one trip from an airport to a book event, The Kid appears in the backseat of a limousine. He’s aware that the driver up front can’t see him, and he’s ready to test the author’s assertion that he’s just a character made up in his mind.

“Why am I not real?” The Kid laughs.

“Because I have a condition,” the protagonist says. “I see things. People too. They say it’s some sort of escape valve for pressure on the mind, probably caused by some sort of trauma. But I don’t go in on that. I haven’t had any type of trauma in my life . . . Nothing worthy of a Lifetime network movie or anything like that.”

Trauma eventually takes readers from the misadventures of the book tour to the dirt roads of Bolton, the hometown of Soot — and Mott as well, raising yet another conundrum. Is Mott’s Hell of a Book a novel, or is it more fact than fiction about a Black novelist from the South?

“Nestled in the sweaty armpit of Carolina swampland, the town of Bolton is the land that time forgot,” he writes. “The main exports of Bolton are lumber and black manual labor. The wood comes from the forests and swamplands — all of which are owned by the local paper mill — and the labor comes from the town’s seven-hundred-odd residents. I wish I could tell you that there’s something more than those two chief exports that comes out of Bolton, but there’s nothing else. Bolton isn’t a town that gives, but neither is it a town that takes. It’s the type of place that keeps to itself. It’s self-sustaining, the way the past always is.”

The past and the present need to confront, and reckon with, what generations of Black Americans have endured.

“Down in this part of the world, we got it all: fifty-four Confederate flags planted along the Interstate, statues put up by the daughters of the Confederacy, plantations where you can have wedding pictures taken of the way things used to be, we got lynchings, riots, bombings, shrimp and grits, and even muscadine grapes,” the novelist writes.

“Yeah, the South is America’s longest-running crime scene. Don’t let anybody tell you otherwise. But the thing is, if you’re born into a meat grinder, you grow up around the gears, so eventually you don’t even see them anymore. You just see the beauty of the sausage. Maybe that’s why, in spite of everything I know about it, I’ve always loved the South.”

It’s also the place where the protagonist, The Kid and Soot converge — without fully solving the air of mystery that surrounds them throughout the book. The enigmatic threads Mott so adroitly weaves together become more tightly stitched toward the end. Hell of a Book will make you think while also entertaining you on a helluva journey.

“Laugh all you want,” the protagonist writes as he and The Kid come to the end of the journey, “but I think learning to love yourself in a country where you’re told that you’re a plague on the economy, that you’re nothing but a prisoner in the making, that your life can be taken away from you at any moment and there’s nothing you can do about it — learning to love yourself in the middle of all that? Hell, that’s a goddamn miracle.” OH

Anne Blythe has been a reporter in North Carolina for more than three decades covering city halls, higher education, the courts, crime, hurricanes, ice storms, droughts, floods, college sports, health care and many characters who make this state such an interesting place.