Omnivorous Reader

Courage and Candor

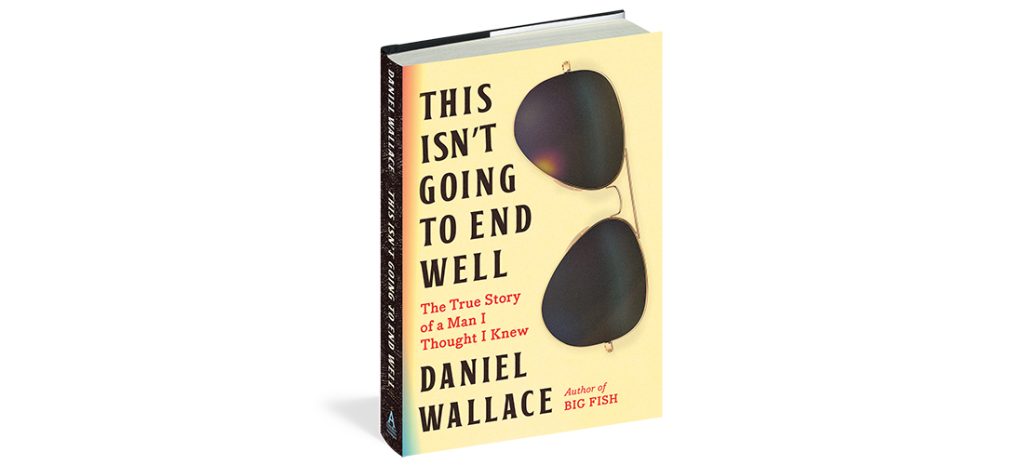

Daniel Wallace’s thought-provoking memoir

By Stephen E. Smith

If you read the promo material for Daniel Wallace’s new memoir, This Isn’t Going to End Well: The True Story of a Man I Thought I Knew, you’ll assume the message is straightforward: Hero worship is an exercise in disillusion. But the “hero” in Wallace’s memoir isn’t a hero in the accepted sense (the sociological definition for “significant other” is a more accurate term); and the message, although essential and timely, is predictably ambiguous.

Wallace is the author of the bestselling novel, Big Fish, and six other much-praised works of fiction, and the qualities evident in his earlier works are perfectly transferable to his first foray into nonfiction. He crafts a compelling narrative that pulls the reader headlong into a story whose energy never wanes. He’s thoughtful and thought-provoking. He makes sense of the past in order to free the reader to face the future, and he writes with courage and candor.

Wallace introduces his hero, his future brother-in-law, William Nealy, in a scene where he happens upon Nealy attempting a perilous leap from the rooftop of the family home into a swimming pool 25 feet below. Nealy takes flight, plunges into the water, climbs out and repeats the jump over and over. “It was pretty magnificent,” Wallace writes. “It wasn’t some unformed idea I had about masculinity or manliness in him that I was drawn to; I wasn’t into that, then or now. It was just the wildness, the derring-do, his willingness to take flight — literally — into the unknown, an openness to experience and chance that so far in my short life had not been previously modeled to me by anyone.” Wallace admits that he didn’t need to emulate Nealy’s behavior but that he learned “. . . how to become the me I wanted,” and that he would think of that day — he was 12 at the time — as the moment he was born again.

The first third of Wallace’s memoir is a biography of Nealy’s short life: his need for constant adrenalin highs, his success as a cartoonist and writer, his marriage to Wallace’s sister, their loving but troubled relationship, and how Nealy’s example encouraged Wallace to become something other than a cliché — not a writer, but someone “demonstrably unique, amusing,” someone living on the fringes.

Following Nealy’s example Wallace threw himself into several unsatisfying pursuits, eventually settling on the writing of fiction — the telling of quirky tales in which nothing is as it seems — that led to the success of Big Fish.

The Nealys settled near Chapel Hill, where they purchased a large tract of wooded land and William built a house, wrote books and produced cartoons and maps about the challenges of outdoor life. In the context of contemporary existence — the use of drugs and alcohol notwithstanding — it all seemed idyllic, skewed perfection in a humdrum world that was constantly encroaching. But that encroachment became all-consuming when a close mutual friend, Edgar Hitchcock, a drug dealer whom Wallace characterizes as “the kindest man I have ever met, so smart, funny and loving,” a dealer who confesses that “selling drugs is the final frontier,” is murdered.

The second part of the memoir centers on the mystery surrounding Hitchcock’s death. Nealy became obsessed with finding the man who murdered his friend, and the road led almost immediately to a likely suspect. Relying on simple intuition, Nealy was able to identify the culprit when he first shook his hand. “It was a notion that would be lodged into the marrow of his very being and would not be dislodged, not ever, not for as long as he lived.”

For purposes of the memoir, the suspect’s name is Stanley, a personable enough acquaintance whom Nealy “befriended” in an attempt to discover the truth surrounding Hitchcock’s murder. When Hitchcock’s body was discovered five months after his disappearance, Stanley began to subtly reveal his culpability.

It’s a long and tangled tale that leads to Stanley’s indictment and his eventual release because of convoluted legal circumstances that hindered prosecution. Nealy was powerless to avenge his friend’s murder, and his continuing obsession with the unpunished culprit damaged his marriage to Wallace’s sister. For one of the few times in his adult life, Nealy found himself powerless to influence events. His need to control the uncontrollable becomes apparent in a brief journal entry: “My whole life has been a struggle against the world to preserve my ‘being’ and it’s put me in dire conflict with the people I love . . . I MUST NOT LET THEM SEE WHO I REALLY AM!”

Nealy committed suicide in his early 40s, Wallace’s sister died in 2011, and Wallace inherited their ashes and Nealy’s journals, leaving him to piece together the events that led to his friend’s tragic end. The journal entries aren’t particularly revealing, but one laconic passage exposes the source of Nealy’s recklessness. Nealy’s hero, a Scoutmaster, sexually assaulted him while at summer camp. Nothing more is revealed about the encounter — and what more needs to be said? A physical dissociation from oneself is the inevitable outcome of such a traumatic event and might explain Nealy’s reckless behavior.

Wallace is left to manage his grief and grapple with the psychological pain suffered when the person upon whom he modeled his life proved himself fallible. He eventually comes to what he believes is a satisfactory understanding of William Nealy’s life and death, but that solution isn’t simple or straightforward. There are no easy answers — and the conundrum remains: What becomes of us when our significant other stumbles? “Can we ever know why we are who we are,” he writes, “the recipe that makes us the unique, bewildering, beautiful and sometimes insane creatures we end up becoming?”

Wallace doesn’t shy from the final truth: There are many ways to die — murder, suicide, illness — and he’s philosophical about the state in which we find ourselves: “. . . there appear to be no safe places left in the world, on our streets or in our hearts.” How true are those simple words?

This Isn’t Going to End Well is not an easy or uplifting read, but it is a memoir borne of intense experience and introspection, which is the only available panacea for what troubles us. Suicide is a perilous subject for the writer and the reader, but Wallace acknowledges that contemplating the taking of one’s life is the most damaging secret a person can have. The “Author’s Note” lists The National Suicide Prevention Lifeline number. OH

Stephen E. Smith is a retired professor and the author of seven books of poetry and prose. He’s the recipient of the Poetry Northwest Young Poet’s Prize, the Zoe Kincaid Brockman Prize for poetry and four North Carolina Press Awards.