OMNIVOROUS READER

Finishing Touches

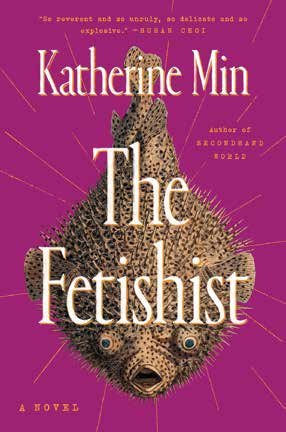

How Katherine Min’s last novel came to be

By Anne Blythe

The story about the making of The Fetishist, Katherine Min’s posthumously published novel, is almost as interesting as the book itself. It has been touted as a novel ahead of its time — a comic, yet sincere, tender and occasionally befuddling exploration of sexual and racial politics.

The story is told through three main characters: Daniel Karmody, a white Irish-American violinist from whom the novel gets its name; Alma Soon Ja Lee, a Korean-American cellist, who’s only 13 when the first of many fetishists she encounters whispers, “Oriental girls are so sexy”; and Kyoto Tokugawa, a 23-year-old Japanese American punk rocker who devises a madcap assassination plot to avenge the man she believes to be responsible for her mother’s suicide.

The novel starts 20 years after the estrangement of Alma and Daniel and ends with them reconnecting. In between, readers get to see Kyoto’s zany failed assassination attempt of Daniel and subsequent kidnapping. They’ll learn of his dalliances with a cast of women — many of them musicians, such as Kyoto’s mother, Emi — while he longed for the excitement and thrill he felt with Alma.

The intertwining of the narratives of these protagonists and the intriguing significant others in their orbits lead to alluring plot twists and a timeless appraisal of the white male’s carnal objectification of Asian women. But let’s start with the end of the book and the touching afterword by Kayla Min Andrews, Min’s daughter, a fiction writer like her mother, who explains how The Fetishist came to be published.

It almost wasn’t.

Min was diagnosed with breast cancer in 2014 and died in 2019, the day after her 60th birthday. She was an accomplished writer who taught at the University of North Carolina at Asheville for 11 years, as well as a brief stint at Queens University in Charlotte. Her first published novel, Secondhand World, a story about a Korean-American teen clashing with immigrant parents, came out in 2006 to literary acclaim and was one of two finalists for the prestigious PEN Bingham Prize. During the ensuing years, Min worked on what would become her second and final novel, The Fetishist, reading portions to her daughter over the years.

“My new novel is very different from Secondhand World,” Min told her daughter during a phone call Andrews details in her afterword. “It’s going to have many characters, omniscient narration. Lots of shit is going to happen — suicide, kidnapping, attempted murder. It’ll be arch and clever, but always heartfelt. I’m gonna channel Nabokov. And part of it takes place in Florence, so I have to go there as research.”

Min completed a draft of The Fetishist sometime in 2013, her daughter writes. “I assumed she would pass it to me when she was ready,” Andrews wrote. “But she was still revising, polishing.” Then the cancer diagnosis hit.

Although fiction had long been Min’s forte, she stunned her family shortly after getting the news, letting them and others know that she no longer was interested in what she had been writing and instead found purpose in personal essays examining her experiences with illness and dying.

“She never looked back,” Andrews wrote. “When anyone asked about The Fetishist, Mom would say, ‘I’m done with fiction,’ in the same tone she would say, ‘I’m a word wanker,’ or, ‘I’m terrific at math.’ Matter-of-fact, with a dash of defiant pride. She didn’t refer to The Fetishist as an ‘unfinished’ novel. She called it ‘abandoned.’”

And that was that.

As Min’s life was coming to an end, she and Andrews discussed many things, such as where she wanted her “remaining bits of money” to go, and how the playlist for her memorial service should include The Clash’s “Should I Stay or Should I Go,” DeVotchKa’s “How It Ends,” and Janis Joplin’s “Get It While You Can.”

“What we did not discuss in the hospice center was her abandoned novel. Or her essay collection. Or anything related to posthumous publishing,” Andrews wrote. After several years of grieving, therapy and a new celebration of her mother, Andrews and others saw to it that The Fetishist, found nearly completed in manuscript form on her mom’s computer, would be shared with others. Andrews helped fill in the story’s gaps.

“I am so happy Mom’s beautiful novel is being published; I am so sad she is not here to see it happen,” Andrews wrote. “I’m happy The Fetishist’s publication process is helping me grow as a writer and a person; I’m sad Mom’s death is the reason I’m playing this role. I suppose I no longer conceptualize joy and sorrow as opposites, because everything related to The Fetishist’s publication makes me feel flooded with both at once.”

Sorrow and joy are among the emotions that flood through The Fetishist, too. Min had it right when she told her daughter her novel would be “arch and clever, and very heartfelt.” The author’s note at the beginning of the novel sums it up well:

“This is a story, a fairy tale of sorts, about three people who begin in utter despair. There is even a giant, a buried treasure (a tiny one), a hero held captive, a kind of ogre (a tiny one), and a sleeping beauty,” she advises her readers. “And because it’s a fairy tale, it has a happy ending. For the hero, the ogre, and the sleeping beauty, and for the giant, too. After all, every story has a happy ending, depending on where you put THE END.”