OMNIVOROUS READER

Sense of Urgency

The stories that need telling

By Stephen E. Smith

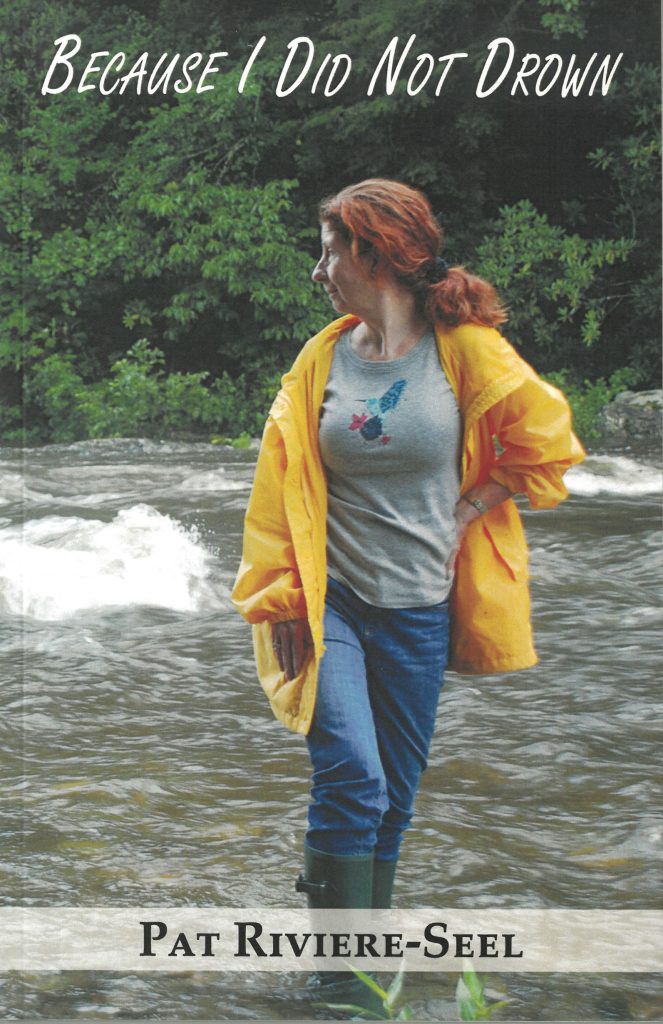

It happens to every writer. The moment comes, sometimes sooner than later, when it’s clear that he or she won’t live long enough to write every story that needs telling. The unwritten stories can be offered as spoken anecdotes, which, of course, vaporize the moment they’re uttered, so getting the stories down in print becomes a source of energy and inspiration. Pat Riviere-Seel’s collection, Because I Did Not Drown, derives its urgency from her desire to have the stories remembered — and to be remembered herself. “How long will the work of art last? Who will remember the artist . . . ?” she writes in her essay, “Unknown Artist.”

Reviere-Seel is the author of four poetry books, most notably the well-received The Serial Killer’s Daughter, which was published in 2009 by Charlotte-based Main Street Rag Press. Because I Did Not Drown explores both the exceptional and mundane — “kitchen talk,” the need for perseverance, the joy of pets (in this case cats), a stray fig plant growing by the back stoop, gun control, the loss of old friends, food lovingly prepared, an enthusiasm for jogging, “disenfranchised grief,” extraterrestrials, etc. Each prose chapter is written in straightforward journalistic prose and intended to convey helpful insights into contemporary life.

She begins her collection by recounting her personal experience with the COVID shutdown. She ends the book by detailing the ill effects of the pandemic’s aftermath, topics few writers have tackled (Sean Dempsey’s A Sad Collection of Short Stories, Cheap Parables, Amusing Anecdotes, & Covid-Inspired Bad Poetry is an amusing exception). This reluctance to write about the COVID experience can be attributed to what readers and writers might perceive as proximity aversion: the shock of COVID is still too much with us, and we’ve yet to sort out its spiritual and political implications. Reviere-Seel takes up the subject head-on: “But as the pandemic stretched into a second year, I became more frustrated, angry, and cranky. I missed my poetry group. I missed my friends. . . . We stayed home. We wore masks. We stayed six feet apart. We were grateful to be alive. . . . What had begun as a public health issue became a political issue. The usual anti-vaccine talk mingled with the talk of ‘the government can’t tell me what to do.’” Her concluding essay, “After the Pandemic,” suggests that kindness is the only possible remedy for a virus that continues to mutate: “Be kind. Most of us did not want to infect our family, our friends, our neighbors, or the checkout clerk at the grocery store who showed up for work every day. Genuine kindness is a balm, a gift, a grace.”

In her chapter “Talking About It,” she is straightforward about her struggles with breast cancer. “I didn’t talk about my experience with breast cancer,” she writes, but the death of an aunt who ignored a lump in her breast inspired her to share her experience. “Early detection and medical advances in treatment have meant that breast cancer is no longer the death sentence so many feared fifty years ago.” Her interaction with the medical community will be of particular interest. When she was denied an immediate needle biopsy, she reacted appropriately. “Nice was not working so I threw a fit, a nice-woman-goes-feral southern ‘hissy fit.’ A redhead-gone-rogue tantrum . . . I was paying for a service, medical care, and I wanted — no, demanded — a say in when and how that service was delivered.” Her story is a paradigm for all women and men who find themselves caught up in our often lethargic and convoluted medical system.

The course of her disease followed a predictable path, but she made the necessary decisions to preserve her life. The description of her battle with breast cancer is timely, honest, reassuring and possibly lifesaving.

Following each of the prose passages, a poem explicates or explores the theme of the preceding chapter. The poems are well written and could stand on their own as a chapbook. “After the Diagnosis,” for example, follows the chapter on breast cancer:

There are nights — more

than you ever thought you could endure —

when sleep will not come

your thoughts — no, not thoughts —

the deep well of unknowing appears

endless. You try summoning

visions of sunrise, a shoreline, bare feet

running across packed sand. But morning

fog covers this foreign landscape.

Everything you knew for sure yesterday

washed away with the tide, predictable

too the magical thinking, maybe. Abandon

the dock, row your way into the nightmare, further

out is the only way back.

The use of verse to add emotional impact to the short personal essays may strike some readers as unnecessary. At the very least, the transition from journalistic prose to poetry is complex, requiring a complete shift in sensibility and focus. Nevertheless, she forces readers to grapple with many of our most vexing problems.