SAZERAC

August 2025

Unsolicited Advice

August, it turns out, is the month that most babies are born in the United States. Editor Cassie Bustamante and her older brother are both early-month Leos, born a couple years apart. Knowing that, we don’t have to guess what many Americans are up to in early November, when the weather cools and the days darken. Brown chicken brown cow, if ya catch us. We thought we’d share a list of words we’re fond of that sound like they’d make beautiful baby names, but which we beg you not to use for your August child.

Calamity. Sure, it means sudden disaster, but it rolls adorably off the tongue. And wouldn’t Callie be a sweet nickname?

Dash. Em dash, en dash, DoorDash. Frankly, we like all the dashes. It could even be short for Kardashian, but, whatever you do, never — ever — call them Hyphen.

Lattice. Like Gladys — and makes us think of flowering vines. Or atoms arranged in a crystalline solid, whichever floats your boat.

Typhus. Dionysus was the Greek god of wine, vegetation and fertility. His brother, Typhus, may have been the god of lice, chiggers and fleas.

Arugula. She’s feminine but a little peppery, too. And we bet anyone with this name won’t fight you on eating her greens.

Imbroglio. Sounds masculine and Italian and we’re here for it. Google the meaning before you use it, though, or you might find yourself in “an acutely painful or embarrassing misunderstanding.”

Sage Gardener

What’s in a name? Well, everybody who’s had a halfway decent English teacher knows that dandelion is derived from the Anglo-French phrase “dent de lion” (lion’s teeth, from the leaf’s indented teeth). But did you know that tulip comes from the Turkish “tülbent,” meaning turban; or that the petunia’s name is from the Tupi word petíma for tobacco, stemming from how the two plants are botanically related; or that azalea is Greek for dry, parched and withered, so named for its ability to thrive in a dry climate?

Probably not, unless you subscribe to Merriam-Webster’s Word of the Day.

It’s my guess that the author of that piece probably has a copy of Diana Wells’ 100 Flowers and How They Got Their Names, along with William T. Stearns’ Dictionary of Plant Names for Gardeners. And I suspect his or her copy is as tattered as mine is.

So let’s start with the dogwood, our state flower, whose wood was supposedly used to build the Trojan horse and whose berries turned Odysseus’ men into pigs. That, according to Wells, who also says the tree’s leaves, bark and berries “have been used to intoxicate fish, make gunpowder, soap and dye, make ink and clean teeth.” You’ve doubtless heard the legend that the old, rugged cross was made of dogwood, and Jesus, feeling the tree’s remorse, transformed it henceforth into a twisted dwarf so that it could never be used for another crucifixion. As for its name, I’m understandably partial to the 1922 theory of L.H. Bailey that its leaves were used to shampoo mangy dogs.

The pine, our state tree, springs from the Latin “pinus,” which etymologists guess (they do a lot of that) derives from a form of the verb “pie,” which means “to be fat or to swell,” with their opining it’s a reference to the pine’s sap or pitch.

Let’s just skip over orchid, which comes from the Greek “orchis,” meaning testicle. And who wants to dwell on the origin of forsythia, named after English gardener William Forsyth, whose recipe for Forsyth’s fruit-tree-healing plaster consisted of cow dung, lime and wood ashes amplified by a splash of soapsuds and urine?

Let’s just go back to Merriam-Webster’s Word of the Day, which once featured plant names that sound like insults. Go ahead, call someone a hoary vervain, stink bell, bladderwort or a dodder. I could go on and on, but my editor has a thing about brevity. So I’ll close with my favorite names of wildflowers — whorled tickseed (whorled means a pattern of spirals or concentric circles), Jacob’s ladder, sweet William, Dutchman’s breeches, foam flower, American boneset, Joe Pie weed, white turtlehead and lanceleaf blanket flower. Pure poetry on the stem or vine. What is it about our wanting to know the names of plants and animals, as if that little tidbit of knowledge gives us some kind of power? And what is it about a plant’s name that seems so intriguing? As my guide once blurted out after two weeks on a tributary in the furthest reaches of the Amazon River, “Bailey, most people just want to know the name of the dingus, and once told, they shut up. But you’re relentless and keep asking questions.” I told him that it was in my job description as a reporter and an incredibly nosy parker. Besides, I said, I was an English major — until I changed my major to Classical Greek. He just shook his head.

Window on the Past

Back in the 1950s when families still swam in Lake Hamilton, most moms chatted on the shore as they kept a watchful eye on their children. But not Betty. She just wanted to be left alone with her magazine. And who can blame her?

Just One Thing

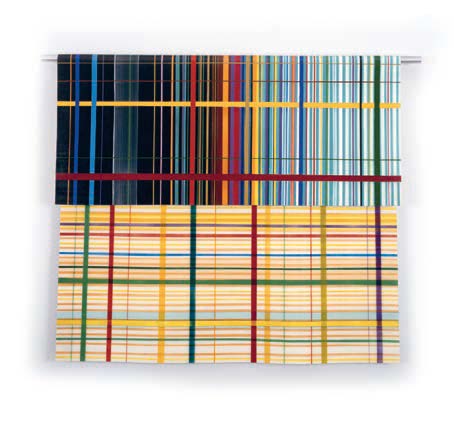

As children, we’re taught to recognize patterns. Our music teacher has us clap out one-two, one-two-three. Our science teacher shows us how to recognize patterns in nature’s wonder — the gills of a mushroom or the arrangement within a DNA molecule. Often, as adults inundated with information, we forget to take a moment to appreciate how patterns stimulate our brains. Weatherspoon’s current exhibit, “Pattern Recognition,” reminds us to find the beauty and meaning in them. Linda Besemer’s Baroquesy, 1999 — featuring acrylic paint over aluminum rod, is part of the Weatherspoon collection on display in this exhibit. California-based Besemer knows a thing or two about pattern recognition and society’s strictures about the use of color. “What’s so predictable about the ‘too colorful’ rejection is that it implies that some color is OK, but too much is unacceptable,” she told Scottish artist and writer David Batchelor just a few years after this piece’s creation. She went on to say that she thinks “that the real problem with color is its containment and regulation.” Which, she says, reminds her of how artists have regarded the female body throughout the history of Western art. Submerge your mind into Weatherspoon’s world of pattern — and so much more — through Jan. 10, 2026. Info: weatherspoonart.org/exhibitions_list/pattern-recognition.

Memory Lane

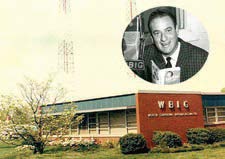

Leaving Lowe’s on Battleground one weekday, I felt a massive pang of nostalgia. The center of that entire property, directly across from ALDI, was the location of the studio and tower for WBIG 1470 AM radio, where Bob Poole broadcast his enormously popular morning show, Poole’s Paradise, throughout the ’50s, ’60s and ’70s.

The quick-witted, basso-buffo voiced, self-anointed “Duke of Stoneville” relocated to Greensboro from his New York network perch in 1952. Soon after, Bob and my father became drinking buddies. As a toddler visiting WBIG’s “Poole Room” while he was broadcasting live, I joined in whistling his theme song, which made Bob burst out laughing. As a teenager, some mornings I’d drop by the station with joke and trivia books.

After faithfully awakening Gate City denizens for 25 years with an audience share that will never be equalled, Bob Poole signed off mere weeks before his death in 1977. Legendary WCOG DJ Dusty Dunn inherited the “BIG” morning slot. In an interview conducted years ago, Dunn recalled negotiating his contract and, of all things, being asked if he wanted batteries included in his employment package: “I said, ‘Batteries? Batteries for what?’ She said, ‘Well, we gave Bob Poole batteries for his flashlight when he wakes up in the morning so he didn’t have to turn on the lights and wake his wife up.’ I couldn’t believe it!”

On the afternoon of November 20, 1986, after celebrating 60 years on the air, the parent company informed WBIG’s general manager that the station would go dark at 6 that evening. Shocked staffers and longtime on-air personalities gathered for a tearful sign-off led by Dusty Dunn.

That decision was basic economics — a relatively small operation was nestled atop an entire city block along Battleground Avenue’s exploding retail corridor, a plot of dirt far more valuable than any revenue a weak AM radio signal could generate.

The last shred left of WBIG’s existence on Battleground is Edney Ridge Road, separating ALDI and Lowe’s, in the 1950s paved for and christened after the founder of the station whose call letters were an initialism for We Believe In Greensboro.