SAZERAC NOVEMBER 2024

Sage Gardener

As I’m writing this, most Americans are a lot more interested in who will be president than what sort of garden they’ll plant.

Not Marta McDowell, who penned All The Presidents’ Gardens in 2016. From George Washington to Barack Obama, she digs up the dirt, so to speak, about who had a perennial obsession with plants. George and Martha Washington, John and Abigail Adams, along with Thomas Jefferson, had gardens and ambitious plans for plants — before the British burned down the White House in 1814 (after the U.S. Army burned down what became Toronto). At the very least, presidents had vegetable gardens since expenses for family food and banquets came out of their own pockets.

James Monroe moved into a mansion under construction, inheriting a yard with the sort of mucky mess that accompanies reconstruction projects. It was John Quincy Adams, McDowell points out, who, faced with a tumultuous presidency and the death of his father, sought solace in, as he described it, “botany, the natural lighting of trees and the purpose of naturalizing exotics.”

To give you an idea of what Adams had to work with, McDowell writes, “To keep the lawns at least roughly trimmed, he arranged for mowers with scythes to cut the long grass for hay, and sometimes borrowed flocks of sheep.” Adams did have a full-time gardener to help him, John Ousley, an Irish immigrant. Following a plan that the plant-and-garden-crazed Jefferson had drafted, the duo got down and dirty. Each morning, after a brisk swim in the nearby Potomac, Adams spent several hours in his garden to “persevere in seeking health by laborious exercise.” McDowell writes, “His was a garden of celebrated variety.” In the two acres he carved out, Adams boasted that you would find “forest and fruit trees, shrubs, herbs, esculent (edible) vegetables, kitchen and medicinal herbs, hot-house plants, flowers — and weeds,” he added, revealing how honest a gardener he was. Adams also collected white oaks, chestnuts, elms and other native trees with an environmental objective: “to preserve the precious plants native to our country from the certain destruction to which they are tending.”

As the latest occupant — and gardener — moves into the White House in January, may I suggest that McDowell’s book might serve as a soothing antidote to the inevitable drama of nightly news and daily headlines.

— David Claude Bailey

That Computes

We say “data boy” to Patrick Fannes, who freely offers his time and knowledge to turning tech trash into treasure. Caching a collection of Windows- and Mac-based tablets, laptops and desktop computers (no more than seven years old), Fannes wipes them clean of all private data, refurbishing as needed before placing them in the hands of disadvantaged children. Though he holds a degree in computer science, he says, “In life I am a lay, ordained Buddhist monk and a doctor of Chinese medicine, serving my community to make this world a better and kinder place.” His friends and associates call him Shifu, the Chinese word for master or teacher, a term of respect. Through Big Brothers Big Sisters, Shifu has worked to provide 200 computers over the last 15 years. If you have an old computer collecting dust, let him give it a second life. And don’t worry — “Your private data will be erased from the computer hard drive and a binary code will be written across the entire surface of the drive nine times so that retrieving any information is impossible.” By donating your tech trash, you’ll not only make your house and the Earth cleaner; you’ll be giving a local child the necessary tools to set them up for success in life. To donate, email Fannes: onecodebreaker@gmail.com.

Booked for a Cause

In Asheville author Robert Beatty’s latest book, Sylvia Doe and the 100-Year Flood, Sylvia Doe doesn’t know where she was born or the people she came from. She doesn’t even know her real last name. When Hurricane Jessamine causes the remote mountain valley where she lives to flood, Sylvia must rescue her beloved horses. But she begins to encounter strange and wondrous things floating down the river. Glittering gemstones and wild animals that don’t belong — everything’s out of place. Then she spots an unconscious boy floating in the water. As she fights to rescue the boy — and their adventure together begins — Sylvia wonders who he is and where he came from. And why does she feel such a strong connection to this mysterious boy?

Known for his Serafina series, Beatty will be donating 100 percent of his earned royalties from Sylvia Doe and the 100-Year Flood — a story he’s been writing for several years — to the people impacted by the catastrophic floods caused by Hurricane Helene in Asheville, North Carolina where he lives. The real-life 100-year flood struck at the same time the book was scheduled to launch. (Ages 8 -12.)

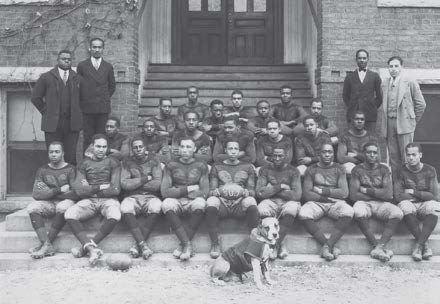

N.C. A&T's football team, circa late 1930s.