What’s Enough?

A sage reveals the trick to a contented life

By Jim Dodson

A few weeks ago I read in The New Yorker about a group of Silicon Valley billionaires who’ve built luxury retreats in some of the remotest parts of the planet, safe houses designed to allow their owners to survive a global catastrophe — stocked with enough good French white wine and military hardware to hold out indefinitely.

A short time later, I read about a second group of young Silicon Valley billionaires funding a top-secret scheme to bio-engineer a “God Pill” that can cure everything from cancer to flat feet and make human mortality as obsolete as the typewriter.

According to Newsweek, this latter group of “visionaries” includes the billionaire co-founder of PayPal who is making plans to live for at least 120 years. A fellow described as the “godfather of the Russian Internet,” meanwhile, says his goal is to live to 10,000 years of age, while a wealthy co-founder of Oracle finds the notion of accepting mortality “incomprehensible.” Sergey Brin, co-founder of Google, meantime, simply hopes to someday “cure death.”

As Newsweek points out, “The human quest for immortality is both ancient and littered with catastrophic failures. Around 200 B.C., the first emperor of China, Qin Shi Huang, accidentally killed himself trying to live forever; he poisoned himself by eating supposedly mortality-preventing mercury pills.”

Centuries later, the answer to eternal life appeared no no closer at hand. “In 1492, Pope Innocent VIII died after blood transfusions from three healthy boys whose youth he believed could be absorbed.

A little closer to modern times, in 1868 America, Kentucky politician Leonard Jones ran for the U.S. presidency on the platform that he’d achieved immortality through prayer and fasting — and could give his secrets for cheating death to the public. Later that year, Jones died of pneumonia.”

Dreams of immortality have beguiled and eluded human beings for as long as we’ve walked upright on the Earth, immune to the wisdom of every spiritual tradition that reminded mortal man that life’s bittersweet impermanence — and one’s perspective on the matter — determines whether every day is regarded as a gift to be savored or a good reason to pack up and head for the hills.

As I read about these lavish billionaire retreats and quest to make human mortality irrelevant, in any case, I couldn’t help but think about the summer I realized I was a mortal pipsqueak who wouldn’t be around forever.

It was 1962 and school was just out for the summer. Third grade was in my rearview mirror and I had a new neighborhood in Greensboro plus a Black Racer bike upon which to go adventuring.

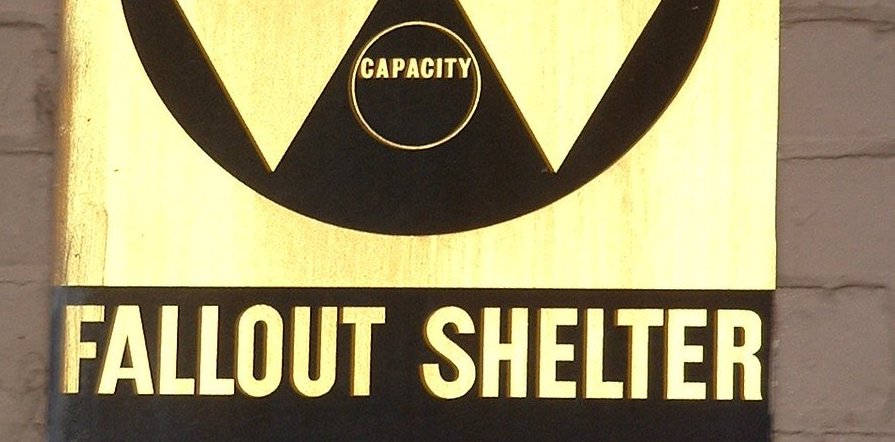

Even better, my new neighborhood pals were talking about the bomb shelter that “creepy Mr. Freeman” had constructed beneath a shed in his backyard in our new subdivision. I’d read in Life Magazine that bomb shelters were the latest suburban passion, being constructed in backyards all across America amidst widespread fears of a “nuclear apocalypse.”

About that same time, an episode of The Twilight Zone depicted a group of folks having a birthday dinner party with neighbors when they learn that America is, in fact, under nuclear attack. The hosts flee to their new bomb shelter in their basement, which is only large enough to accommodate the family. Tempers explode, panic ensues. The neighbors batter down the bomb shelter door only to learn that the report of a pending nuclear extinction was simply a human error, a false apocalypse.

For the balance of that summer, however, I became obsessed with the notion of an “Apocalypse” and Mr. Freeman’s homemade bomb shelter.

I even suggested to my father that we build one in our yard, helpfully offering an original sketch of what my ideal bomb shelter might look like — the Flintstone family cave meets Jules Verne’s Nautilus submarine equipped with a storeroom full of hotdogs and Lorna Doone cookies.

My sketch even depicted the wasteland above ground ― a cindered moonscape inspired by photographs of Hiroshima I’d seen in an Associated Press photo book of the Second World War.

“How many people can fit in your bomb shelter?” the old man casually wondered.

I explained it would be a bomb shelter for four, with room for our dog.

“I see. Well, how would you feel knowing all your new buddies and schoolmates who didn’t have bomb shelters were left up top and gone?”

This was a wrinkle I hadn’t foreseen, a horrible prospect that led to pose the more essential question? Did he think there was going to be an apocalypse anytime soon?

His reply surprised me.

“Probably so. Someone is always having an apocalypse — waiting beneath a clock for a loved one to die or a baby to be born; for the fever to break or the crisis to end,” he added, pointing out that the original Greek translation for Apocalypse – as mentioned in the Bible — simply meant a revelation of something not yet known, perhaps the awakening of a new and better world.

He even had an answer to creepy Mr. Freeman’s bomb shelter.

“Rather than burying yourself in the backyard, maybe you should just grow up and help create that new and better world. Our time on this Earth is brief. The trick is to use that time wisely ― and learn what’s enough.”

It took me many years before I realized what he was telling me.

By the time my older brother and I were teenage wise guys under the influence of classic American “fumes” – i.e. gasoline and perfume – this sort of Aesopian wisdom prompted us to nickname our uncommonly upbeat old man “Opti the Mystic,” owing his unshakable good cheer and embarrassing habit of quoting long-dead philosophers and spiritual sages to our impressionable dates when they least expected it.

Decades later, when we reminisced about my bomb shelter summer, Opti and I happened to be sitting together in a crowded pub on the rainy Lancashire coast of England, sharing pints of warm beer following a rained-off round of golf. Though you wouldn’t have guessed it to look at him, my father was dying of cancer, and this was our final golf trip together, a long-talked-about odyssey to see the places where he fell in love with golf as a homesick Air Force sergeant just prior to D-Day.

Among other revelations on this trip, I’d learned that my father had been through his own versions of an apocalypse — first a tragic plane crash that killed dozens of people including children he knew in the village where he was stationed; a second one when his dream of owning his own newspaper in Mississippi went up in smoke after is silent partner cleaned out the company bank accounts and headed for parts unknown. That same week, unimaginably, my mother suffered a late-term miscarriage and my dad’s only sister died in a car wreck outside Washington, D.C.

“How does one survive a week like that?” I asked my father,

He smiled, shrugged. “I suppose it was because I’ve learned that it’s not what you get from this life that really matters — but what you give and leave behind. Whatever you give comes back to you many times over in the form of unexpected blessings.”

My father was 80 years old that rainy afternoon in western England. Not only could I suddenly appreciate why he was the perfect fellow to moderate the men’s Sunday morning discussion group at our church in Greensboro for more that two decades, but how fortunate I was to have him, if only for a precious few weeks and months.

I was 41 years old that evening, a father with two small children back home in Maine; a son already in grief over the thought of losing my life’s original mentor and hero, wishing my young ones could somehow have their own years with this wise and funny grandfather.

I must have said this out loud.

My father simply smiled and sipped his beer.

“Don’t waste time regretting what you don’t have. Every moment is a gift that can feel like eternity if you pay close attention. Focus on the now.”

And with this, he laughed. “Maybe you can put this in a book someday. In the meantime, it’s your turn to buy the beer.”

It was Vintage Opti. One year later, I did put this moment in a book.

Reading about the wealthy Silicon Valley billionaires who crave more time and “plan” to live forever, avoiding a catastrophe they fear may occur at any moment, reminded me about my Bomb Shelter summer and the calming wisdom of my funny, philosophical father.

Not for the first time – and in light of a world that always teetering on Apocalypse of one kind or another – this got me thinking about of “what’s enough?”

I jotted a few things down.

Enough for me is an old house where every creak or groan underfoot sounds like a sigh of contentment, the music of home.

Long walks around Paris are the stuff of everyday magic. I miss them. But walking the dogs with my wife around the block in the evening is even better.

The Japanese garden I’m building will probably take years to finish – though a garden can never truly be finished, anyway.

I hope to write at least four or five more books, have many more suppers with friends and see my old dog Mulligan live at least that long. This would make her 24 years old.

That’s enough for now, a gift Opti the Mystic gave me long ago.

“This is why we are in the world,” advised the Sufi mystic Bawa, one of his favorites. “Within your heart is a space smaller even than an atom. There, dear ones, God has placed 18,000 universes.”

Contact Editor Jim Dodson at Jwdauthor@gmail.com