Blue Angels of the Garden

By Jim Dodson

As August wanes, dragonflies begin to disappear from the garden. Their lease, like summer’s, is far too brief.

I’m always sorry to see them go.

The other evening I was watering my parched perennial bed when a pair of iridescent dragonflies zoomed up out of nowhere, performing a delightful pas de deux in the gentle spray of my hose. Though I don’t know my dragonflies as well as I’d like to, I believe these might have been male (blue) and female (green) Eastern pondhawks on a dinner date.

According to a recent piece in the New York Times, new research shows dragonflies may be the keenest hunters in the animal kingdom, snatching and devouring 95 perfect of their prey on the wing – not bad for a dainty insect that belongs to the shortlist of insects most people like, alongside lady bugs and butterflies.

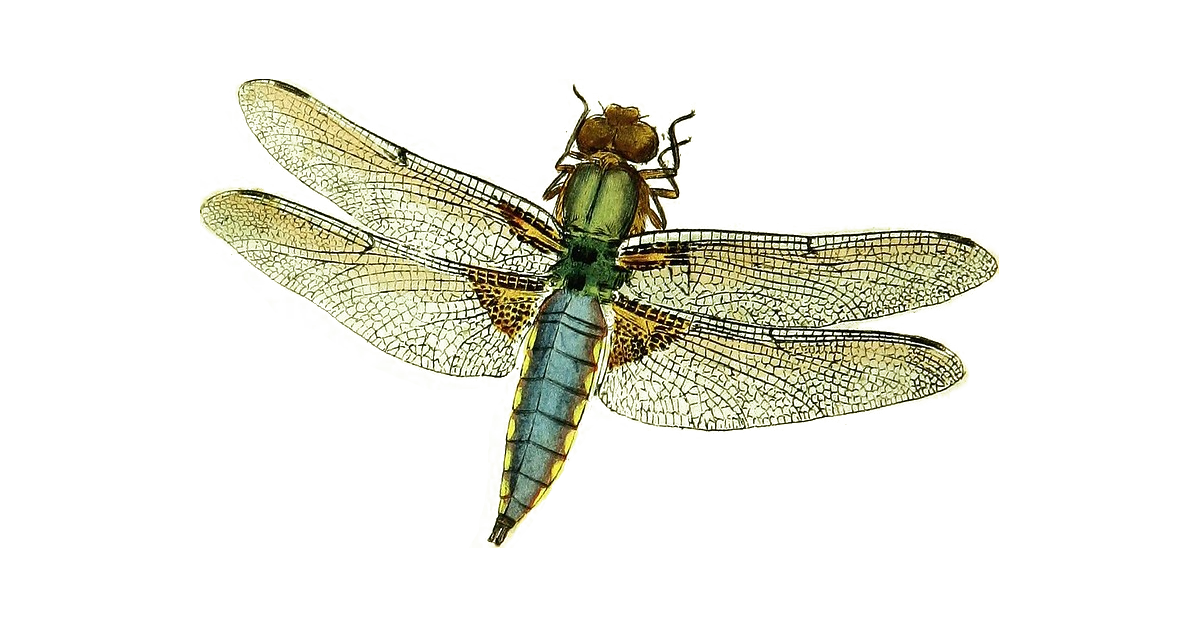

Equipped with compound eyes that are believed to be the sharpest the insect world, a dual sets of wings that flap only 30 times a second (compared to a bee’s 300) enabling a dragonfly to stop mid-flight and move in all directions at will, these ancient acrobatics are believed to be the swiftest predators in the air, capable of reaching speeds of 35 mph or higher, which perhaps accounts for their voracious eating habits and need to consume up to thirty house flies or mosquitoes in an hour, all while inflight.

For this simple reason alone we should honor theses beautiful killers of summer, which prey on any number of stinging and annoying insects that make being outside for a lowly human on a fine summer evening sometimes more painful than it’s worth. Despite their fearsome optics, dragonflies actually can’t sting humans or animals, though in their aquatic nymph form– which takes up well over half their lives — they can indeed deliver a sharp but harmless bite.

The research team that determined the dragonfly’s impressive flying and eating habits also points out that their sophisticated nervous systems can lock on and track specific targets through clouds of other flying insects with such impressive skill a mosquito or house fly rarely sees the creature that swallows it whole.

The public clamor over the growing use of unmanned aircraft or drones by military and private commercial entities – promoting drones as an efficient way to deliver everything from intel on natural disasters to Fedex packages but raising significant concerns about the right to privacy – takes on an interesting new level of meaning when you learn that our military studied the killing efficiency and acrobatic brilliance of dragonflies for decades in order to decipher how they operate so efficiently. A dragonfly’s brain, it turns out, may be the closest things in the insect world to our own, the ultimate onboard computer designed for hunting and gathering – only better.

As a species, they predate us on this earth by hundreds of thousands of years, dating from the carboniferous period 300 million years ago when dinosaurs roamed the earth and at least one species of dragonfly, long extinct, was two or three feet in length and weighed approximately the same thing as a medium sized dog.

Dragonflies belong to a relative small order of species called Odonata, which translates to mean “Toothed ones,” a reference to the serrated mandibles that crush their prey to a pulp on the fly, with just 7,000 different species that includes their related cousins, lesser-winged damselflies. Species of butterflies and bees, by comparison, number in the tens of thousands.

The fearsome name derives from ancient lore that dragonflies were indeed the progeny of flying dragons. In some places – the bush of Australia, for instance – dragonflies were considered (incorrectly) tormentors of horses and livestock, capable of delivering poisonous stings, while in Medieval Sweden some believed they were sent by evil spirits to weigh the souls of unhappy people.

Most cultures welcome them, though, as signs of vibrancy and good environmental health. In China they’ve long been regarded as symbols of spiritual harmony and prosperity, in Japan chosen by the Samurai warriors as symbols of courage and integrity — creatures balanced in nature. The Irish see them as the preferred winged transport of fairies.

They enter our dreams and our gardens displaying a curiosity that prompted some to believe they might actually be messengers or angels in insect form. One common interpretation holds that dreaming about dragonflies – symbols of beautiful movement and grace – means your life is about to change for the better.

A dragonfly’s life, in fact, is a compelling study in physical transformation. Most of its life is spent in nymph form under the surface of the water, sucking up nutrients like mad until it achieves pupae form and eventually sheds its carapace before flying away for its brief winged dance, rarely living more than a month or two in the air. Perhaps nature’s only compensation for such brevity of life is the dragonfly’s unrivaled flying skills, intelligence and fragile beauty.

Several species have been known to fly 10,000 miles across India and Africa in search of a mate – the real purpose of their glorious colorings and acrobatic skills. Dragonfly love lasts only a few seconds and often takes place, impressively, on the wing. A female lays her eggs in warm freshwater shallows and the males venture off to eat and soon die, a story as old as time.

Several years ago, I was fishing on a lake late in on a drowsy summer afternoon when a small squadron of iridescent blue dragonflies came out of nowhere and swarmed my boat, circling and whizzing by the end of my nose and the end of my casting rod, before flying off in perfect formation. I’d never seen anything like it, a jaw-dropping airshow show of synchronized flying worthy of the Blue Angels themselves. One of the performers even briefly alighted on my low-hanging fishing rod, seemingly as curious about the creature at the other end of the rod. Just then a huge bass lurched brazenly from water, just missing his prey, who darted away in the nick of time.

Last evening after a rain shower cooled off the sweltering afternoon, I had a second chance to study a dragonfly up close and personal, stepping out near dusk in a rush to meet my wife for an early movie only to find a lone pondhawk dive-bombing the upper garden birdbath. I decided it must the same courting male I’d been watching all week. But his beautiful baize-green female companion was nowhere to be seen.

As I watched, this angel of the natural world perched on the edge of the birdbath and let me come close enough to actually get a look into his extraordinary translucent eyes, curious what I might see there. Pride of a new dragonfly papa? Or maybe the grief of a beautiful killer who knows his duty is done, his time left on this earth measured only in day if not hours?

Time, wrote James Thurber, is for dragonflies and angels – the former live too little and the latter live too long.

If nothing else, as summer wanes and the days begin to shorten, the dragonflies of my garden remind me to pause and take note of this world’s passing beauty before it vanishes too – and takes us with it.

Which may explain why, after a moment of sizing me up, the beautiful blue dragonfly zoomed away to dine on a few dozen delicious mosquitos on the moist evening air before life, beautiful life, flew away from him.