Conversations

12 Questions

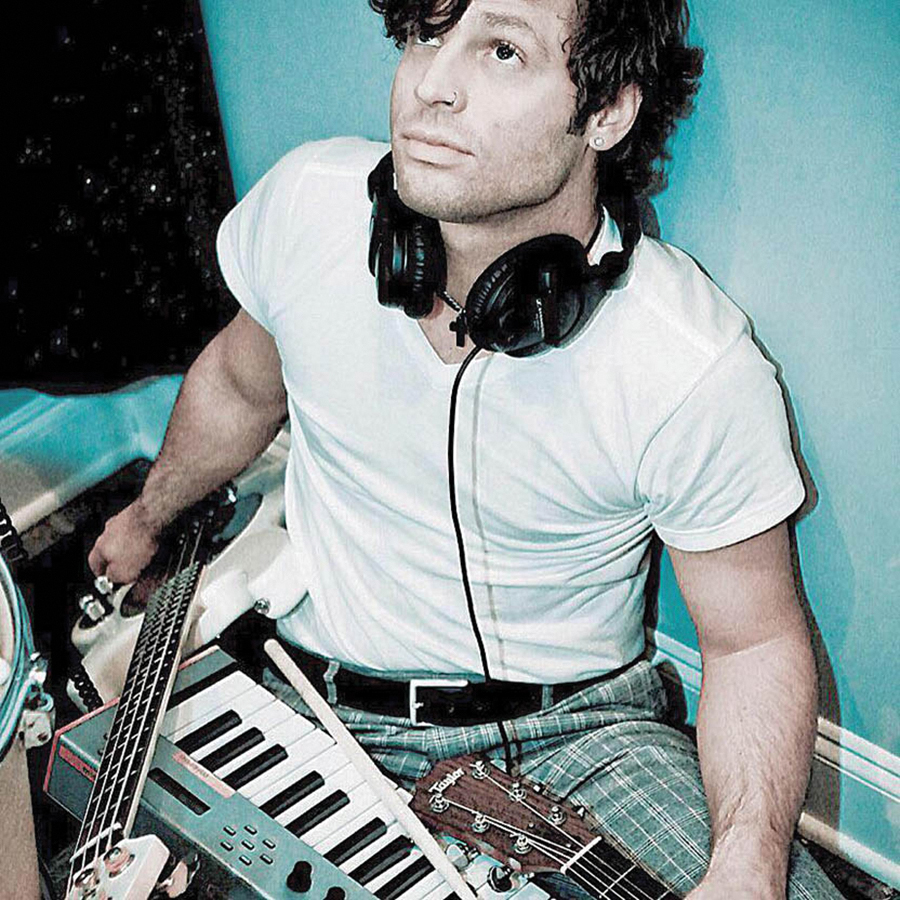

For Greensboro pop virtuoso Joey Barnes, the sun always shines and the hits keep coming

By Billy Ingram

Joey Barnes is an anomaly, a singer-songwriter of extraordinary proportions with an amazing vocal range whose power-pop creations don’t stray too far from his 1980s’ electronic new wave influences. Yet he’s just as comfortable crooning jazz standards with a

Cy Coleman-like harmonic swagger distilled from the days of Bing, Dean and Dinah (Washington not Shore).

In 2006, Joey went from thumping bass for The Patrick Rock Band to bashing skins and cymbals for Daughtry, a local band fronted by Chris Daughtry. They were riding high that year with a quadruple platinum album spawning four hit singles while scoring the No. 1 spot on the Billboard 200. What followed was a whirlwind of international dates and the sort of blank-check, rock ’n’ roll antics one indulges in when there’s a cadre of bodyguards and professional babysitters sweeping up those messy entanglements left littering the landscape behind you.

Joey’s recorded seven EPs and LPs on Nascent Republic Records since 2008, including an impressive live album, “On With The Show,” tracking a one-night-only performance backed by Luna Arcade, Tracy Thornton and the Greensboro College All-Stars. On albums like “A Dance Where Worlds Collide,” his romantically infused Pop Rock candies for the ears crackle with effervescence, tempestuous tunes pinballing from the sublimely melodic to the infectiously facetious.

A voice sometimes smoky, other times Smokey, always searing, this Greensboro native has played London’s Wembley Arena twice, but his roots reach way back into the city’s musical aristocracy.

Can you recall the first time you performed on stage?

Well, both my parents were musicians — it must have been with one of the bands my dad was playing in. I do recall a gig playing drums with Rob Massengale. The Massengale family and the Barnes family grew up together as best friends. I was around 12 years old, my dad was playing with Rob, I sat in on drums and played Peter Gabriel’s “In Your Eyes.”

In the 1990s, I was starting to get with other musicians to try and start bands. I do recall playing at somebody’s house party in a garage. A bunch of up-and-coming young musicians, we all knew about four or five chords. I got up there and just started beating around on the drums and it basically turned into “Wipeout” and everybody really loved “Wipeout” like they had never heard it before. I don’t think I played it very well, but that was the first time I gained the attention of girls.

I always wanted to travel, to see the world, and I wanted to perform. It wasn’t about who I could play to, but where I could go. That old cliché thing where you put pins on a map and say, “I want to go here.” Dreams of doing something, being with your friends, playing music.

On your recordings you play almost all of the parts yourself, how did you master such a wide assortment of musical instruments?

Having them around. They were just there. I was never taught; I just watched. You just sit down with something you’ve never played before, like a trumpet or a clarinet, and squeal and sound like you’re strangling a goose until you get a note out of it. Then you get two notes, three notes, then scales and you’ve got it.

Who influenced you most musically?

The Beatles. They were like the foundation of everything. And Frank Sinatra. I grew up in the ’80s so ’80s’ music was a big deal for me — George Michael, Tears for Fears, The Police, a-ha was one of my favorites. Duran Duran was like my Beatles, they were the Fab Five for me.

I was friends with Warren Cuccurullo who joined Duran Duran after Missing Persons, his supergroup made up of Zappa alumni, broke up.

You knew Warren? That guy is a genius, he’s brilliant. He was single-handedly responsible for bringing Duran Duran back in the ’90s with “Ordinary World.”

On the road with Daughtry, did you feel relegated to playing drums, or was that offset by being on tour with the hottest act in America?

It wasn’t rocket science, it was just bash it out. It was about aesthetics and it was about rock ’n’ roll. So easy but it was fun . . . for a while. As the tour went on, I was seeing how much I could do at one time, so I had a piano to my left while I was playing drums. I was trying to make it interesting but that situation . . . there wasn’t a lot of room for playful or, you know, anything artistic.

As far as touring, I was ready to go. I didn’t have any family, kids, so I was game all the time. A lot of sleepless nights, sleeping on airport floors. The adventure and the experience was what I signed up for. I was just like, “This is going to be a good time and let’s see how long it lasts.” Like George Harrison said, “The farther one travels the less one knows.” I changed over the course of that tour. I became a completely different person. For better and for worse, I suppose. I’ve been consistently progressing since then. I learned a lot about what I love, about art, music and learned a lot about what I don’t want to deal with.

After you left Daughtry, you didn’t get much of a hiatus from the road before you were thrust out before the public again. This time with one of the 1980s symphonic synth bands you admired, a-ha, who had massive hits with “Take On Me” and “The Sun Always Shines On TV.”

They were one of my favorites since I was about 8 years old. One of the cornerstone bands, they were always about crafting great pop songs. Dark and mysterious. They’re from Norway, so it kinda sounds like music you would write when half of the year is cold and dark and gray.

One of my good friends, Jimmy Gnecco, is in a band in the Jersey, New York area called Ours. I’ve been a big fan of his for a long time. We met almost 20 years ago. I played drums for him awhile, opened up for him, so we became good friends. He knew the guitar player, Paul [Waaktaar-Savoy], from a-ha.

As I was getting out of the Daughtry thing, I thought I had almost done everything on my list of things to do, places to go. I thought it couldn’t get any better. Within a couple months, I get a call from Jimmy saying, “Are you sitting down? How would you feel about me, you, and a couple of other people opening up for a-ha in Europe for three months?” I couldn’t believe it. It raised the bar for me personally, It was beyond cooler than anything I did with Daughtry. I cried every night, I couldn’t believe I was there.

Your first time was with Daughtry, but opening for a-ha offered you another opportunity to take the stage at Wembley Arena. The Beatles jammed there, Depeche Mode, The Grateful Dead, Prince, Dylan, Duran Duran.

Playing Wembley was always the pinnacle for me. Everything was about playing Wembley and then to do it again with a different band was pretty insane. The first time I did it, I was in my underwear. Why not?

After that, I toured the United States with my own band. So I ate the road up as much as possible for a decade. Once you’re on the road by yourself, when it’s your thing and it’s coming out of your pocket, your bank account, then you realize this is really tough. Even when you’re making good money.

Being a live performer is a bit like having an alter ego, isn’t it?

I think so. Was it Oscar Wilde who said, “Give a man a mask and he’ll tell you the truth?” I think it’s really good to get in touch with that other person. I think some people are afraid to do that, they don’t know how far they’ll take it into madness. You can lose yourself in the other person. You have to find a balance, to be one [personality] here and another there.

I designed Mötley Crüe’s very first posters. Those skinny boys Nikki and Vince would come peacocking down Santa Monica Boulevard afternoons to our studio in full regalia, neon-colored spandex, makeup, hair crimped to ridiculous lengths. And they wouldn’t even have a show that night.

Not everyone is able to become a David Bowie as the Thin White Duke or Ziggy Stardust. I don’t want to show up at a party and everybody be like, “Oh, there’s Lady Gaga, we see you.” Some people like to draw that attention. I get that but that’s just not me. I can’t stand it, honestly.

Do you prefer recording or live performing?

I prefer the creative process involved in recording. I think that, on certain occasions, if I’m able to take the essence of [a recording], bottle that up and successfully do it justice on stage . . . yeah, then it could be equally gratifying.

For the last decade you’ve worked closely with producer Josh Seawell. What does he bring to your recordings?

For me personally, I come into the studio and Josh facilitates quite easily whatever I hear in my head. He’s a musician as well, and he does put out his own stuff, but he’s been in the engineer seat, the mixing seat, the producing seat, for a long time.

I first met Josh when I recorded with Patrick Rock back in the late-’90s. Josh set up his first studio in his parents’ basement. Our friendship built from there. He stuck with it, invested everything he had in a legit studio on the side of his house with the latest and greatest equipment. And he’s brilliant. To have somebody who has a great ear, that you’re friends with, that you respect. Plus to go to his home. His wife’s the best, his kids, it’s just a really nice atmosphere to be out in the country where you just kind of feel free, to relax and see your vision to fruition. When he started a record label, Nascent Republic, I was, “I’m totally signing with you.”

Josh also does song placement; he’ll get songs on E!, TLC, or Lifetime. The other day one my songs played in a commercial for Turner Classic Movies and I was like, “Yes!”

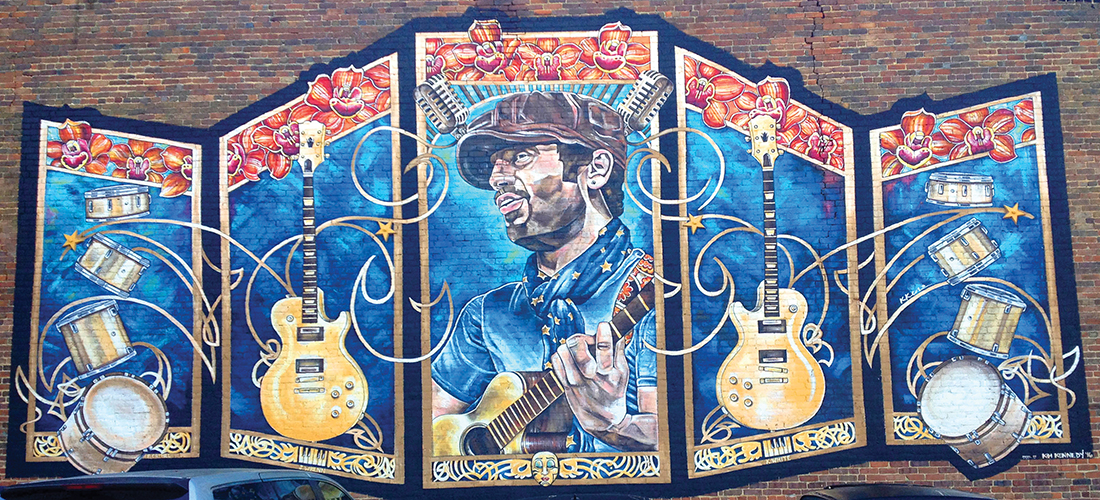

Your image is on the first modern day mural that emerged downtown, a Pop-Art portrait painted on the side of Design Archives. How did that come about?

I met a girl, Kim Kennedy, in Nashville and she’s a muralist. I have no idea how or why, but she knew some people in Greensboro and it just happened. It really was crazy. I still have tons of people randomly sending me pictures of it saying, “Oh, I’m hanging out with you today.” She started something; now murals are everywhere. OH

Billy Ingram covered the underground East Los Angeles punk music scene for a Hollywood bar rag in the early-1980s. He wrote about it in PUNK, the kind of book the whole family can gather around the bar and read together.