How one Greensboro couple went room to room with interior improvements

By Maria Johnson • Photographs by Joey Seawell

Recent retirees Marnie and Jim Fenley wanted a designer’s help with upgrading the two upstairs bathrooms in their Sunset Hills home.

Two bathrooms. That was it.

LOL.

Of course, it’s easy to guffaw now, a year and a half later, considering that most of the couple’s home has been redecorated and everyone is giddy about the outcome.

It happened so naturally, and relatively painlessly, that no one seemed to mind the mission creep, which started, really, with a squirt of envy.

It seems that Marnie’s dear friend, Catherine Harrill, who lives in a Fountain Manor condo (that was featured in this magazine in April 2019) had her digs transformed by the principals at VIVID Interiors, Gina Hicks and Laura Mensch.

Marnie loved the result, and she wanted what Catherine had, only in her own home, with her own stuff and in her own style, which, truth be told, is pretty much Catherine’s style, too.

To wit: Marnie and Jim bought a distinctive turquoise patio chair at The Red Collection consignment shop. Catherine came to visit.

“That’s my chair!” Catherine exclaimed, as if she were laying claim to the curio.

Marnie: “No, it’s not. It’s mine!”

Catherine: “No, I mean I took it to The Red Collection.”

You get the idea.

So Marnie and Jim invited designers Hicks and Mensch — whose names cry out for a Netflix detective series — to their home, a very beige, very boxy, very buttoned-down 1950s residence that’s distinguished on the outside by a Mars-red front door and, come summer, fiery pots of matching geraniums that flare around the magnolia-studded yard inside an iron fence.

Like a splashy tie and pocket square, it’s an exterior ensemble that says, “fun in socially acceptable ways.”

But step inside the home, and whoa Nelly. You’re hit full force by a carnival of colors and styles, a place where funky dances with formal, and prim converses with primitive, and somehow all of those adjectives get along fine.

The profusion of art, especially on the walls, is warm and welcoming to all stripes of expression. The message: Don’t take yourself so seriously.

“See that deer?” says Jim, nodding to a paisley stag’s head over a kitchen door. “I shot it in a fabric store.”

The couple’s playfulness is infectious.

“The first time we went in, we were like, ‘Wow! We want to be like them when we grow up,’” says Gina Hicks. “They have great art and a great spirit, and they definitely have a Bohemian, eclectic style.”

Marnie returns the compliment: “They got us. They completely got us, and they didn’t pressure us.”

But back to “the project.”

Each upstairs bathroom was mid-century small and situated on the main hallway. After the Fenleys’ daughters, Isabel and Jennifer, grew-and-flew the nest, Jim and Marnie used the spaces as his-and-hers dressing rooms; the master bedroom had no en suite plumbing.

By the time they hired VIVID, the Fenleys already had embarked on updating the facilities with new flooring, vanities and tiled showers enclosed by frameless glass.

They wanted help with wallpaper, fixtures, cabinet hardware and lighting.

Hicks and Mensch didn’t hold back. For Marnie’s bathroom, they prescribed bold botanical wallpaper (starring split leaf philodendron, a.k.a., Swiss cheese plant, for the flora-driven) and sleek brushed gold fixtures, hardware and lighting. Using computer-assisted design, they rolled the ceiling with avocado paint.

The overall effect: clean and green.

They gave Jim’s space the geometric treatment, covering the walls with black-and-gold-foil hexagonal wallpaper. Lighting, hardware and accents repeated the color scheme.

The Fenleys were thrilled with the fancy baths.

“We felt like we were in a hotel,” says Marnie.

Mission accomplished. Right?

Ahem.

“We decided we wanted something a little different in the bedroom,” says Marnie.

Playing off a riotous batik-style bedspread that Marnie got at Anthropologie, Hicks and Mensch papered over the faux-painted walls with a peach-tinged material that resembles grasscloth but is actually woven from slender tubes of paper.

To dress the bed, they added a tall headboard, covered with nubby, cream-colored fabric, and framed the space with white, teardrop lamps atop new mid-century style nightstands.

Much to the Fenleys’ delight, the VIVID women incorporated many of the couple’s love-worn pieces: an Oriental rug, an old desk, some green leather chairs, a bureau and dresser, and a remarkable combo clinging to the wall over the dresser: an oval mirror with a frame resembling a white gear cog, and on each side of the looking glass, a white goose that appears to be coming in for a landing, webbed feet outstretched.

“Gina and Laura said, ‘What the hell. They look good. Keep ‘em,’” recalls Marnie, who appreciated the pair’s conservation of furnishings for sentimental and monetary reasons.

Everyone raved about the bedroom.

The Fenleys were done. Yes?

“Fortunately or unfortunately, once you start, it’s hard to stop when you’re trying to perk things up after 35 years,” Marnie explains.

It was true; the upstairs office looked awfully office-y, despite an abbreviated yoga wall complete with metal plates and a padded belt that Marnie and Jim use to stretch their cranky backs.

Marnie demonstrates, using the belt to flip upside down mid-sentence.

“It just feels good,” narrates Jim.

Team VIVID went with the hanging-from-the-trees vibe, tipping the room more toward safari than spreadsheet. For the office walls, they pulled in the same avocado paint used on the ceiling of Marnie’s bathroom. They quite literally dragged down two leopard-print side chairs from the attic. Never mind that the Fenleys’ own tiger, their late orange tabby, a ruffian named Bob, had clawed the upholstery on the back of one chair. The shredded fabric would stay. This was a safari, dammit.

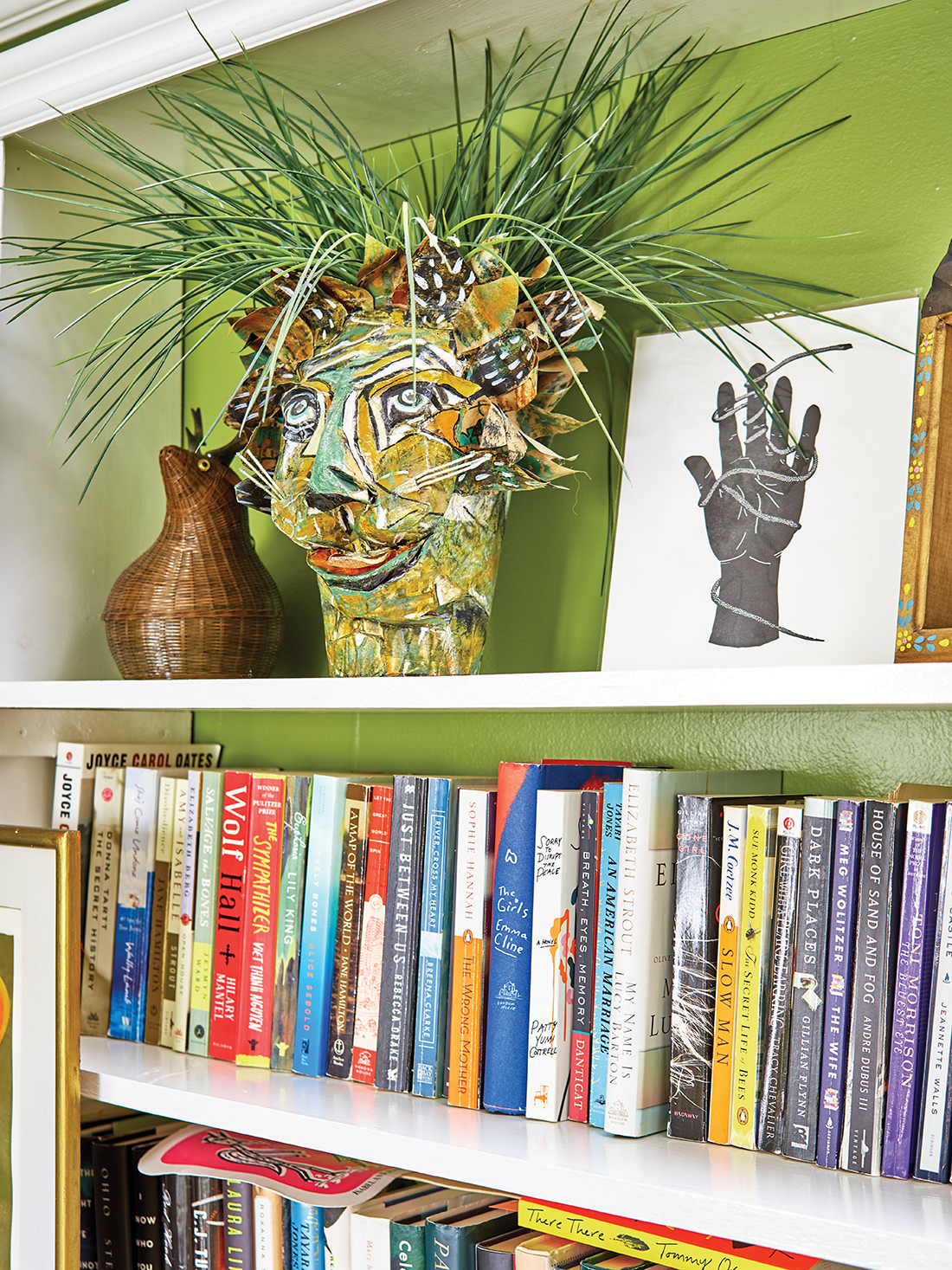

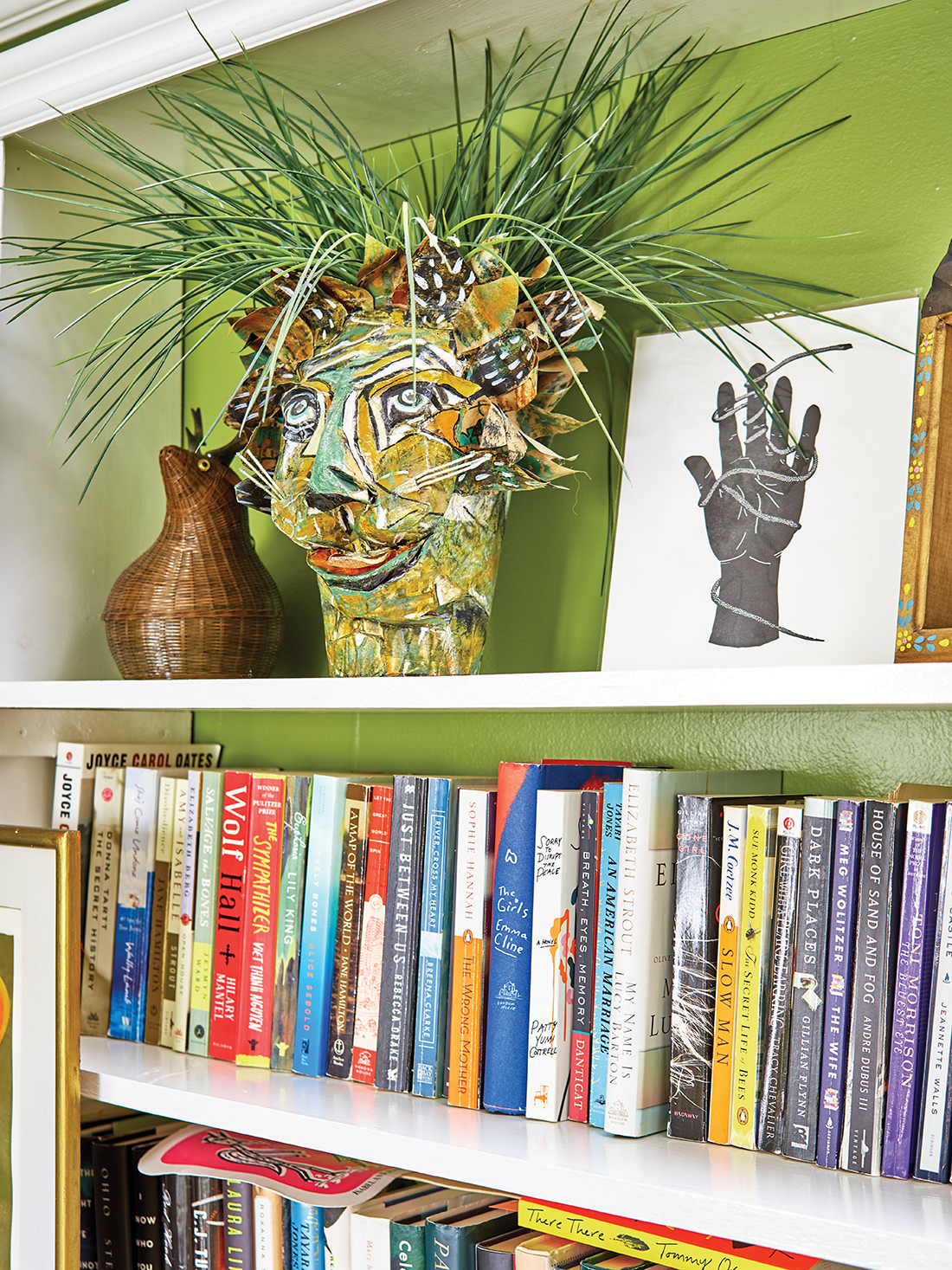

The VIVID gals also brought down a brass and copper burro head that Marnie’Ms mother, Isabel, had bought in Mexico when Marnie’s dad, Jack, went there on textiles business a half-century ago. The zebra-striped lamp on the computer desk would stay. The bookcases would continue to shelter a papier-mâché bear, as well as a crazy cat head crafted by Marnie’s former sister-in-law, Mitzi Fancourt, who gave it as a birthday gift.

“It’s a lion. I’m a Leo,” says Marnie.

Jim, who built the wall-mounted bookcases in the office, reprised another improvement; he repainted the wooden floor with a black checkerboard design he’d brushed on years ago.

“You have to tape, and re-tape and tape again,” he says. “It’s not easy, but it looks good.”

With that, the upstairs was finished.

The End?

“We were like, ‘Well, let’s walk down to the living room,’” says Marnie.

The living room, the Fenleys agreed, needed some attention. But it had great anchors, chiefly a yellow leather sofa that came from Marnie’s mother’s home in Sedgefield. Her mom’s portrait, in profile, hangs across from the tufted sofa. Isabel is a knockout. So is her couch. Visually speaking.

Practically speaking . . .

“It’s the kind of couch you sit on and slide off,” says Marnie.

“We really need to put Velcro on it,” says Jim.

“People do sit on it. It’s just not a place you want to spend a lotta, lotta time,” Marnie explains.

However, the seat makes a great gallery for pillows, one of Marnie’s weaknesses. A shopping trip to High Point’s furniture market netted a fuzzy, blue number that recalls the texture of the Fenleys’ beloved standard poodles.

As counterpoint to the sofa, Jim picked a fuchsia rug, and the couple bagged a cherry-colored wall hanging populated by camels, horses and men in turbans.

They also bought two new club chairs and had them covered with floral fabric in tempo with the room’s bouncy melody of fuchsia, blue and amber.

They calmed the ferment by hanging long, white drapery panels from high-mounted rods, by keeping the sea foam walls, and by extending the cool paint color to the fireplace mantle and surround.

The mantle decorations are pure Fenley: a gilt-trimmed mirror; a bonsai-like vase and branches; and a frilly-framed, acrylic painting depicting a steer skull and owl figure. The painting was made by their New York-based niece, Anna Fancourt, who comes by her artistic chops honestly. Her mother, Mitzi, made the lion head in the upstairs office. Anna’s father, Walter Fancourt — who is Marnie’s brother — is an artist, as well as former co-owner of Liberty Oak restaurant and former chef at Maria’s gourmet deli and catering shop.

“I buy everyone’s artwork in the family,” says Marnie, who expresses her genes in the arrangement of art and in her willingness to take visual chances.

That’s why no one was surprised when she said OK to covering the ceiling of the dining room — did we mention that the VIVID crew moved on to the dining room next? — with a black and white wallpaper that Marnie describes as “Dalmatian spots.”

Neither did it surprise anyone to know that Marnie and Jim — “I just shook my head ‘yes,’” Jim says — allowed the figurative Dalmatian to run off-leash, peppering the walls of the adjoining kitchen and keeping room, a compact living area clipped to the kitchen.

The outbreak of spots seemed to have been pre-ordained, says VIVID’s Hicks. After the wallpaper was up, everyone noticed that the flecks matched the shirt of a woman depicted in a painting in the keeping room. Also, the inky dabs were the reverse image of white flakes in another painting the Fenleys owned: a dog in a snow storm. They brought the dog in from the cold, transplanting him from the home’s main stairwell to the sunny nook.

And then, finally, the Fenleys stopped.

Faked you out.

They did one more room: the den.

“The transformation in this room is probably the greatest,” says Jim.

“It’s where we live,” says Marnie.

The couple replaced their saggy thrones with contemporary swiveling winged chairs and ottomans — all done in plush periwinkle — along with fresh pillows. They ditched dingy grasscloth for walls the color of spicy mustard.

The backdrop highlights treasures acquired over 36 years of marriage: an elaborately carved oak buffet that came from Jim’s great aunt Sally; an epoxy covered, Picasso-like painting that was bought at a Lindley Park art fair and later framed by blue window shutters; a novelty lamp with Japanese figures resembling Kewpie dolls, camped under a telescoping red metal shade.

More unconventional light emanates from an oil painting of a clown looking wistfully toward a blue sky, a gift from the Fenleys’ friend, Dan Stoner.

“Everybody says it’s scary, but I love the colors,” says Marnie.

“He had a fear of clowns, and he was working through it,” says Jim, 72, who understands that healing is a process. In 2015, he retired as clinical director of Fellowship Hall, a drug and alcohol treatment center in Greensboro.

Marnie, also 72, has a background in counseling. And catering. And creating a home from what started — in 1984, when they bought it— as a fairly bare stage on which their lives would play out. Over time, the Fenleys dressed the home with unique sets and props.

“When I think about how it started out, it has morphed and morphed and morphed into something we really love. It’s like we’ve been able to fulfill it,” Marnie says.

“When I look at old photographs, it’s pretty amazing how it’s grown and changed,” Jim adds.

Marnie summarizes: “Jim says he’s dying here. We’re going to stay as long as we possibly can.”

Refreshing their home in stages, expanding the scope and paying as they went — a typical experience, according to designers Hicks and Mensch — was much less daunting than plunging into a complete overhaul from the beginning.

“I think that’s the only way I got it past Jim,” says Marnie, laughing. “Otherwise, it would have been a nonstarter.”

Jim acknowledges this fact with a smile.

Marnie says their daughters prefer more monotone interiors, but granddaughter Jacquelyn values their juicy aesthetic.

“I told her, when your grandfather and grandmother die, you’d better get over here, and get what you want as fast as you can,” says Marnie. OH

Maria Johnson is a contributing editor of O.Henry. She can be reached at ohenrymaria@gmail.com.

Photographs contributed by Vivid Interiors

Diana

Diana