Papadaddy’s Mindfield

Why We Teach

Because love trumps money

By Clyde Edgerton

After a recent day of teacher protest in Raleigh, a Buzz from the StarNews went something like this: “If they want more money, why do they teach?”

One answer: “To educate young people in such a way that America doesn’t end up with about 40 percent of its adults who think like you do.”

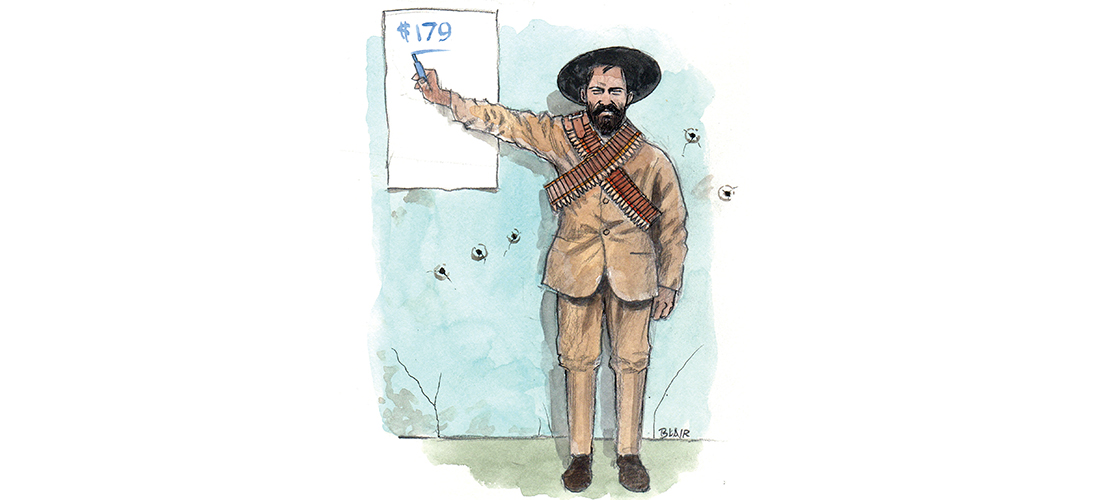

For some reason, I’m guessing the question-asker is an adult male — kind of irreverent in an annoying way, annoyingly pushy, laughing in an annoying way about being pushy. This guy, let’s call him Norman, probably has a boring, well-paying job, and loves to watch TV and collect, say, bicycle spokes. He made Cs in high school, finished two months of college, then dropped out because it was boring.

Today, his boring job pays a pretty good salary — for a person with the creativity of mud. He has health insurance and is going to retire as soon as possible so he can spend the rest of his life watching TV and collecting bicycle spokes. He likes quiz shows and action films — the ones that aren’t too complicated. He likes to bet on sports. He dreams of being a millionaire. He knows that greed makes the world go around. Greed makes people work hard. Teachers aren’t greedy, so they don’t work hard.

I had Norman pictured as about 40 years old, making maybe 48 to 54 grand a year, but I just now had a switch-glitch.

I had him wrong.

Norman is actually a multimillionaire who lives carefully, counting his money. He got some lucky breaks. He thinks of himself as cool — though he doesn’t collect bicycle spokes — he has no hobbies; he’s a little less creative than the first Norman. He does have two Thomas Kinkade paintings except one of them doesn’t have the little original spot of real paint. He has a cool Mercedes. He’s 62, and has had some face-work. Maybe a little too much — since he looks kind of like a 38-year-old who’s constipated.

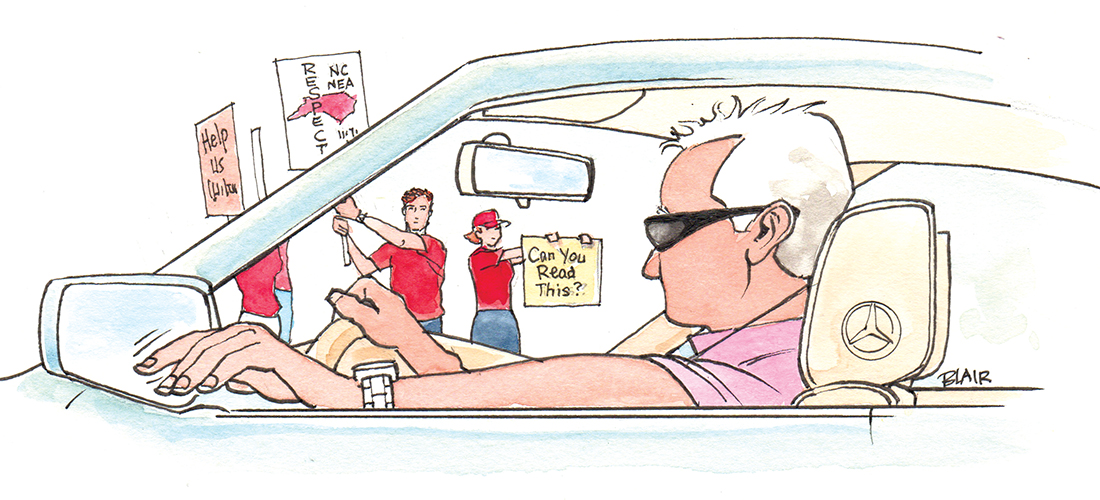

He’d volunteer in a public school if he could find one that paid $1,200 per hour. But why should he spend even a second thinking about public schools? He has a portfolio. And a nice $920,000 yacht. He has a membership in a high-end country club. (Don’t get me wrong — there are people in country clubs without face-lifts.) His thought is: What is public education anyway but a place for poor kids? Like the children of teachers. He, like the first Norman, asks, “If they want more money, why do they teach?”

They teach because most of them love teaching. Love it in spite of a collapse of respect for what they do — in spite of a surprisingly large percentage of their country’s budget going for “leadership.” Whoa. In spite of bosses with a Bluetoothed ear who sometimes visit in schools that might well expel a student who refused to un-Bluetooth her ear. In spite of insane testing mandates from the government. In spite of people working around them for $11 an hour — with their state government and local school board rubber-stamping those poverty-making wages.

They love teaching. They are rewarded by the look in the eyes of a child who is excited about learning something — like, say, a new language, how to play clarinet, or how to solve a calculus problem. They believe that look in the eyes of a curious child might, with some luck, be morphed into a dream that does not depend on money for happiness, a dream that finds purpose in serving others, that creates a permanent curiosity about the world, a permanent respect, even love, for their neighbors — even neighbors who have far less than they do. The deep excitement in teaching and learning is water for a thirsty nation.

While it’s appropriate to say, “Thank you for your service” to a vet, it’s just as appropriate to say, “Thank you for your service” to a teacher. Both make our nation safe. Both have tremendous power — one to destroy, one to build.

If they want more money, why do they teach? To build student insight and character through knowledge, and thus make our nation better able to handle something as risky as democracy. OH

Clyde Edgerton is the author of 10 novels, a memoir and most recently, Papadaddy’s Book for New Fathers. He is the Thomas S. Keenan III Distinguished Professor of Creative Writing at UNCW.