The Creators of N.C.

The Feature Is Female

The future might be, too

By Wiley Cash

Photographs By Mallory Cash

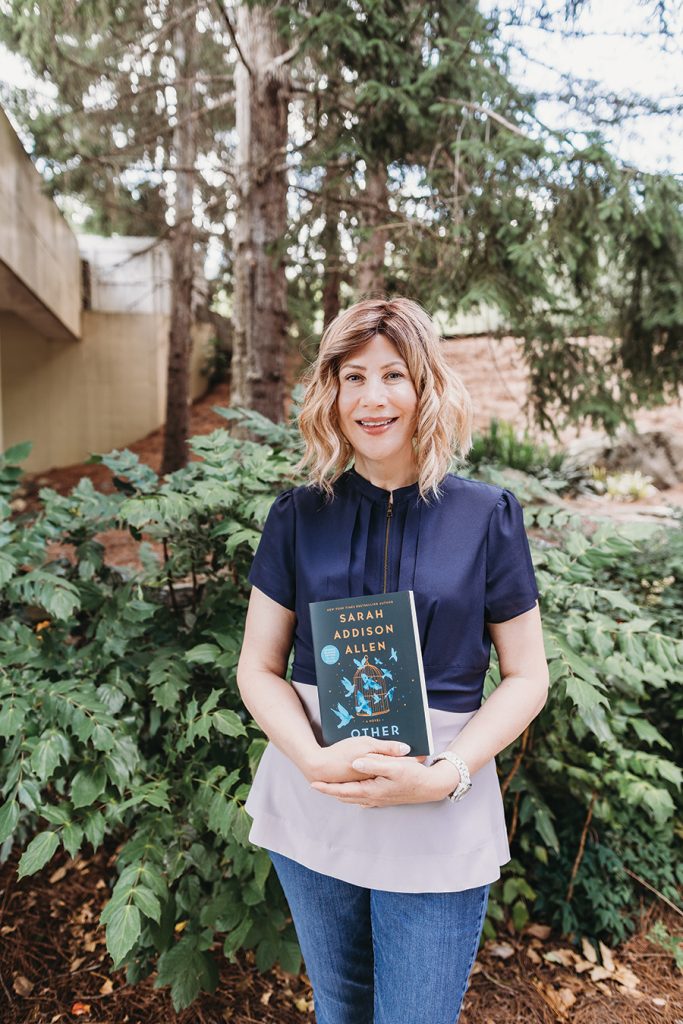

Erika Arlee and Kristi Ray, co-founders of Wilmington’s Honey Head Films, grew up on sets. For Erika, one of her first on-set experiences was as a child growing up in Chapel Hill during the making of Attack of the Killer Dog, which she wrote, directed and co-starred in with her sister and one of their friends. Recalling the intensity of her childhood fascination with film, Erika says, “I wanted to make movies, and I wanted to hold the camera so badly.” Her early special effects included a plush stuffed animal dog that was tossed at the actors from offscreen so they could be, in fact, attacked by a killer dog.

For Kristi, who grew up in rural eastern North Carolina near New Bern, her first on-set experiences also took place at home, and included casting, producing and directing her older sister and cousin in back porch performances of Beauty and the Beast, Grease! and other movies that had left their mark. “I was always the director and the producer and the costumer,” she says. “And I would cast my cousin and my sister in the lead roles to get them to participate, and then I would play every other character that no one wanted to play.”

Regardless of whether they were handling stuffed animals while shouldering boxy VHS cameras or perusing thrift stores to outfit a cousin for a homemade play, both Erika and Kristi can trace their creative drive to those early days as girls who were desperate to see their dramatic visions come to life on the stage and screen.

That energy, which is apparent to anyone who spends any amount of time with these two women, combined and gathered force to create A Song for Imogene, the first feature-length film by Honey Head. While Erika and Kristi’s paths to filmmaking seem preordained, their path to one another was a little less certain.

After growing up in Chapel Hill, Erika attended the University of North Carolina, double majoring in English and dramatic arts with a minor in creative writing. Although she’d always been drawn to film, it didn’t seem like something that was accessible on campus or in town, but Erika had seen Broadway productions, so she threw herself into acting and dance, thinking those outlets might be the only way for a Southern kid from a small town to find the stage. She never lost her interest in film or her desire to hold the camera, however, and by 2014 she was living in Wilmington, auditioning across the Southeast and working behind the camera with local writers and producers.

Unlike Erika, who headed east to Wilmington after college, as a 17-year-old Kristi went west to Los Angeles to pursue acting after high school. “I probably ran out of money like a year into my journey there,” she says. “I came back to North Carolina and auditioned for a feature film that was being produced in the Triangle, and I got cast in the lead role.” Kristi’s performance as Charlotte in Pieces of Talent was noticed, and she was soon offered a scholarship to the Lee Strasberg Theatre and Film Institute in New York. As much as she benefited from her education, Kristi found that the atmosphere in New York wasn’t as supportive as the film community in North Carolina, so she came home and settled in Wilmington.

I don’t know how many successful relationships, business or otherwise, begin on Craigslist, but this one did. Erika had joined with a local actor to write and shoot a horror film that featured a number of their friends, but they needed a female lead, so she posted a call on Craigslist, which Kristi happened to find and answer. Their bond was almost immediate. Soon, the two women were filming one another for audition reels, reading scripts together, and sorting through what seemed to be a shrinking market of opportunity for young women in the film world.

Aside from vapid roles that relied on little more than youth and appearance, “there just wasn’t anything interesting for young women that we were finding,” Erika says.

“This was the time when Winter’s Bone almost won an Oscar and there were a lot of really cool roles out there, they just weren’t around the Southeast, and they weren’t being offered to blonde girls who looked anything like us,” Kristi says. “We wanted to prove that we could play someone who wasn’t just a cute little girl at the mall.”

Erika wrote a short film about two sisters called Lorelei that was written specifically for her and Kristi so they could reach toward what they knew was the full range of their abilities. The story of two women settling their mother’s estate in rural North Carolina eventually served as the backstory for A Song for Imogene, which stars Kristi and was directed by Erika.

The two women who had come up through the ranks while shooting one another’s audition tapes are now at the helm of a feature film that’s in post-production and positioned to go out on the international film festival circuit. The relationship they’d built during their formative years, and through the experience of writing and shooting commercial work, had created a foundation that now guided them.

“Erika’s an incredible director. She was the first female director I’d ever worked with, so there’s this huge trust that I’ve always had,” Kristi says. “And her writing is really good, so it’s hard to do it poorly.”

The crew for A Song for Imogene was 70 percent female, including eight female interns from university film programs from around the East Coast. For many of these young women, it was their first time on a film set. Erika and Kristi allowed them to explore what interested them while also playing key roles in the production. While they watched the interns bond they couldn’t help but recall their own experiences of doing the same just a few years earlier. Now, they had become the teachers and mentors.

“When these young women go out into the professional world and work on sets, they won’t be afraid,” Kristi says. “They will have already gotten their anxiety out the door in a safe environment with us.” Erika and Kristi hope that the experience will leave these young women more mental space and emotional energy to collaborate and build community.

Pondering their own struggles in the industry while witnessing their interns thrive, Erika and Kristi had an idea about how to help the next crop of female filmmakers enter film programs or step onto sets with confidence. They partnered with educator Sam McCleod to create a summer camp, called Shoot Like a Girl, that focuses on female filmmakers from the ninth to 12th grades.

“We’re trying to get them at that stage where they’re a little bit more reserved,” Erika says.

The two-week camp, which kicked off its inaugural session in July, allowed the girls to learn cinematography, wardrobe, lighting and grip, screenwriting and directing. By the end of the camp they were casting and shooting their own short films. To ensure that the experience was accessible to girls regardless of their economic circumstances, Kristi and Erika were able to raise $18,000 from community partners to fund seven of the 12 girls at the camp. They’re excited to see what this first group will do next.

“To feel this empowerment and to be in a cohort of women is something that’s going to be invaluable,” Kristi says.

Erika and Kristi’s new film, A Song for Imogene, is certainly a female feature, and, with Honey Head and Shoot Like a Girl, the future of film might be, too. OH

Wiley Cash is the Alumni Author-in-Residence at the University of North Carolina at Asheville. His new novel, When Ghosts Come Home, is available wherever books are sold.