A Remembrance of Greensboro’s music scene

By Jim Clark

In this month of festivals when the playbills are filled with the faces of John Coltrane and scores of jazz and folk musicians headed our way, and as Jaime Coggins once again sets the stage for the Tate Street Festival, it is not surprising that a quarter-century-old debate should reemerge in the pubs and eateries of College Hill: Who really is the face of Tate Street music?

And without fail, someone will always answer quite definitively, “That would just have to be Emmylou Harris.”

But for many of us who have long called Tate Street home, these are fighting words, evoking as much passion as the geopolitics of Southern barbecue sauces and rubs.

And yes, I’ve always had a dog in this fight — well, actually three.

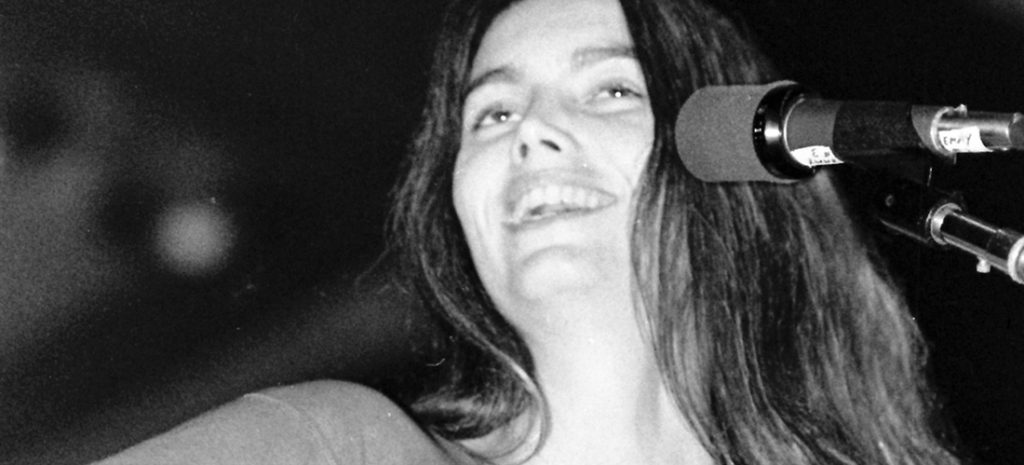

Now please understand that I, like most of us connected to Tate Street or UNCG, am right proud Emmylou Harris took her first steps toward stardom in our neighborhood. And we admire too her leaving behind the stage of what was then Aycock Auditorium, where she played leading roles in The Tempest and in The Dancing Donkey, to cross the street and begin singing at the Red Door at a time when it was taboo for campus women to even go down to Tate Street.

At the Red Door, she was paid $10 a night to sing, plus all the beer she could drink — and she didn’t even drink beer at all.

Some of the Red Door patrons weren’t quite sure what to make of her. One of them was Ted Keaton, longtime Greensboro musician and former keyboardist/vocalist for Kallabash. “She was this nice, quiet hippie girl. We really never had any idea she would go so far,” he recalls.

But surprised by her success or not, fans have given Emmylou an enthusiastic welcome whenever she has returned to Greensboro.

In April 1976, ten years after leaving the Gate City, she returned to give a concert at the old Piedmont Sports Arena. The Greensboro Chamber of Commerce along with local promoter Bill Kennedy had the day declared Emmylou Harris Day, complete with a birthday party at the old Hilton on Market Street. When she leaned over to cut the cake, her long hair kept spilling over onto the icing, so she asked fans to hold her hair back for her, and several hurried to her aid.

Then in June 1997, she returned again to give a concert at the Carolina Theatre and the Greensboro News & Record review gushed over her performance: “Standing among her quite casually attired comrades, this beautiful lady stood out like a gray-tipped rose in her modest, full-length, maroon-colored skirt. The gold-inlaid walls of the majestic Carolina Theatre were a perfect setting as the angelic voice of Emmylou Harris soared toward the heavens”

So yes, she is definitely one of our musical angels, but the face of Tate Street music after little more than a year singing there a half century ago? No way.

The first face that comes to my mind when I think of Tate Street music is, of course, folksinger/songwriter and poet Bruce Piephoff, who got his start there around 1970, and where he did, as he puts it, “an apprenticeship for ten years: “Back then there was a lot of playing in kitchens, and sleeping on couches,” he remembers. Now with more than twenty-three CDs to his credit, Piephoff’s “Tate Street Blues” defines the spirit of those days when the street was known as Tate-Ashbury.

Young man walking down the street at night

Young man, he’s lookin’ quite a fright

He got the Tate St. Blues

He got nothing to lose

He got the Tate St. Blues

Up all night pickin’ in the kitchen

Sleeping on the couch

Eatin’ fried chicken

He got the Tate St. Blues

He got nothing to lose

He got the Tate St. Blues

(Words & music by Bruce Piephoff, Piephoff Music, ASCAP)

And, of course, then there was Psyche Wanzandae, one of the founding members of the Truth and Rights One Love Reggae Band. In the early ’70s I spent many nights picking him up on Tate Street and driving him to various Greensboro clubs, where a high point of one of his acts was setting himself on fire. I was there the night of his clothing malfunction when the flames on his wristbands refused to go out on their own. Born Terence Quinton Lindsay, Psyche died last year. You can see some of his contributions to the musical scene near and far by watching “Celebrating the Life of Psyche Wanzandae,” available on YouTube.

Someday when the definitive history of Tate Street music is written, probably by the likes of an Ogi Overman, a Grant Britt or a Billy Ingram, there will emerge a panoply of musical faces and places, including Amelia Leung, who opened Hong Kong House in 1971 and who nourished the bodies and souls of so many of the Tate Street musicians for twenty-eight years, including Bruce Piephoff, who would take out the trash in exchange for a meal. Surely there will be a chapter on Aliza Gottlieb of the subterranean Aliza’s Café, opened in 1972, later renamed the Nightshade Café. And, of course, Friday’s, where R.E.M. and Eugene Chadbourne performed and where Henry Rollins from Black Flag rolled across broken glass on the floor. But for now, we have only brief snippets of this rich history, represented, for example, in that fine 15-minute tribute to Tate Street music, Ian Pasquini’s “Tate Street That Great Street,” which went up on YouTube last year. The video appropriately concludes with Bruce Piephoff’s “Tate Street Blues,” with him singing a couple of lines about “Sittin’ on the wall in front of the Hong Kong House / Listenin’ to Electro playin’ Son House.”

Ah yes, Electro, the Tate Street bluesman who twenty-three years ago was literally supposed to be the face of Tate Street music and as a result has become the center of one of Greensboro’s longest running urban legends.

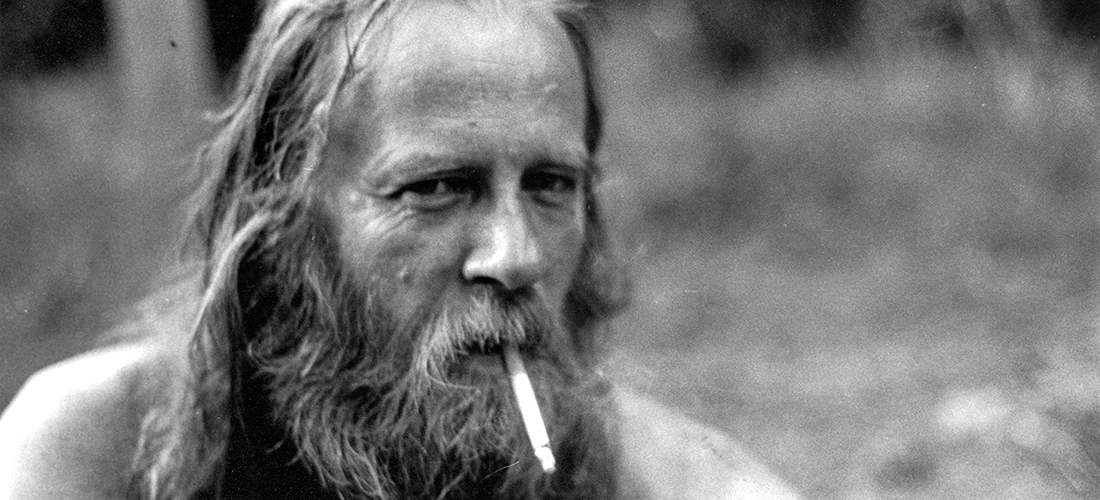

Electro, who has always described himself as “just a hard-core ’60s hippie.” Born Harry Wilton Perkins Jr., after a stint in the U.S. Air Force as a radar technician, Electro arrived on Tate Street in 1969, where he started playing slide guitar. And, yes, he pretty much lived . . . on the street. (These days he is living in a trailer in Roxboro.)

A quarter of a century later, when a group of Tate Street merchants selected communication and design student Michael Crouch to do a mural on the wall at Tate and Walker Avenue, the mural was to feature O.Henry, General Greene, and originally Electro. But some of the merchants objected to glorifying one of the street people, so Electro was supposedly replaced by Emmylou Harris. However, the legend goes, when her handlers heard about this, they objected, and Emmylou was replaced by Dolley Madison, who eventually made it onto the final version of the mural (which, alas, was painted over a few years back).

Crouch at the time of the controversy said he really wanted Electro on the mural, because he was “such a landmark.”

Now a marketing specialist at Guilford College, Crouch insists Electro was only on the planning stages of the mural and was never actually painted on the wall, although many Tate Street denizens still swear they remember the image of Electro on the mural. (Back in those lazy, hazy days we saw lots of things that may or may not have been there.) Crouch did sneak in the words “Inspiration by Electro” at the bottom of the mural.

And, Crouch adds, “I have to re-emphasize that Emmylou was never a part of the mural project in any way — not in my sketches, not in my proposal, not in the concept [or] execution in any way. I hope I have cleared that up; I would hate to see that misconception perpetuated in print. No offense to Emmylou, she simply was not part of my generation’s understanding of the Tate Street area or its history.”

I wish we had known neither Electro’s image (nor Emmylou’s) was ever actually on that wall. As Bruce Piephoff sings in his “Tate Street Blues,” lots of folks sat on Tate Street “waiting for the night,” when interesting things were bound to happen. On some moonless nights, after UNCG had planted thorn bushes on Hippie Hill to keep the street people away, Also Aswell (aka Chuck Alston) dressed in his cosmic ray deflector garb would lead forays unto the hill where he’d plant thorn bush — killing vines. And on other darkened nights bell-bottomed Johnny Appleseeds would sow marijuana seeds among the thorny tares in a sarcastic nod to UNCG as a bastion of higher education. And on still other such nights, there were those who argued for sneaking down to the mural with paint remover where — not to take anything away from Emmylou or Dolley — they wanted to carefully rub away the face of Dolley and then the face of Emmylou to reveal the face of Electro, shining there for all to see the way it should have all along. OH

Jim Clark, the editor of The Greensboro Sun in the 1970s, was one of the organizers of the first Tate Street Festival in 1973. He now directs UNCG’s MFA Creative Writing Program.