Beyond Jaws

The tragedy of the Indianapolis revisited

By Stephen E. Smith

Just when you thought it was safe to go back in the bookstore, there’s a new best-seller about the worst shark attack ever — a book that details the feeding frenzy, past and present, that surrounds the sinking of the heavy cruiser USS Indianapolis on 30 July 1945.

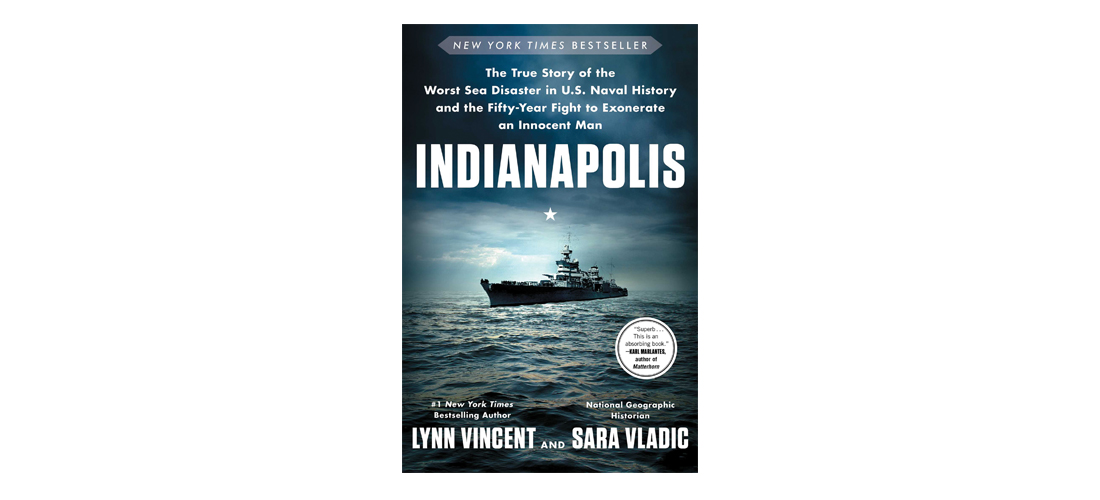

Lynn Vincent and Sara Vladic’s meticulously researched and artfully constructed Indianapolis: The True Story of the Worst Sea Disaster in U.S. Naval History and the Fifty-Year Fight to Exonerate an Innocent Man is the latest in a plethora of books, history specials, movies, documentaries, TV news features, etc. that has, since the cruiser disappeared into the Philippine Sea 73 years ago, contributed to the lore surrounding the demise of the ship and crew that transported the first atomic bomb to the island of Tinian.

If you’re a reader with a basic knowledge of American history, you’re no doubt familiar with the tragic story of the Indianapolis. If you aren’t, anyone who’s seen the movie Jaws will be more than happy to tell you all about it, just as Quint, the shark hunter (played by Robert Shaw), told them: After delivering the components for the bomb, the Indianapolis was cruising at night when the Japanese submarine I-58 fired two torpedoes into the ship, sinking her in 12 minutes. About 300 crew died in the torpedo attack; another 900 went into the water. No lifeboats were launched, no actionable distress signal was transmitted, and the men had only flimsy life preservers and makeshift rafts to keep themselves afloat. Many of the crew died of saltwater consumption, others simply despaired and committed suicide. When the survivors were located almost five days later, only 316 remained to tell the story. Figures vary as to the exact number of the men taken by sharks, but experts theorize that the majority of those attacked had already died of exposure. Still, the horror engendered by a shark attack — the possibility of being eaten alive by a silent, subsurface predator — has resonated through popular culture.

To their credit, the authors aren’t obsessively concerned with sharks, focusing instead on a post-rescue conspiracy surrounding the Indianapolis disaster. In the months immediately following the sinking, the story was eclipsed by news of the surrender that occurred after the dropping of the atomic bombs, but a bureaucratic feeding frenzy began as soon as the survivors were rescued. According to Vincent and Vladic, Navy brass, intent on covering up their incompetence, subjected the ship’s captain, Charles B. McVay III, to a court-martial in which he was convicted of “hazarding his ship by failing to zigzag,” although zigzagging was not required or even recommended in the area in which the Indianapolis was cruising. In an unprecedented move, prosecutors brought in the commander of the I-58, a former enemy combatant, to testify against McVay. The Japanese captain stated emphatically that zigzagging would have made no difference in his attack on the Indianapolis, but McVay was found guilty anyway. He was blamed for the disaster, a reprimand was placed upon his service record, and a deluge of hate mail followed him for the remainder of his life. No other American captain has ever been punished for losing his ship to a torpedo attack. Whether out of guilt for his lost crew or the emotional distress brought on by a failing marriage, the former captain of the Indianapolis committed suicide in 1968.

Vincent and Vladic’s account doesn’t end with McVay’s death. They examine in detail his eventual exoneration. In 1996, a 12-year-old Florida boy, Hunter Scott, took an interest in the story of the Indianapolis and initiated a letterwriting campaign. He was supported by survivors who wanted to honor their late captain and by Sen. Bob Smith, who offered a congressional resolution that finalized McVay’s long-delayed vindication. But the reprieve didn’t come easy, and the military machinations and congressional intrigues surrounding the McVay hearings are at the heart of the book.

As the congressional inquiry neared its conclusion, Paul Murphy, one of the men McVay had led into harm’s way, wrote to the committee reviewing McVay’s court-martial, objecting to a previous report upholding the Navy’s original court-martial findings: “They contain falsehoods, statements taken out of context, and plain mean-spirited innuendos about our skipper and others who have attempted to defend him . . . The Navy report contained personal attacks on Captain McVay’s character. They were unwarranted, and in most instances, unrelated to the charges against him. On behalf of the men who served on the Indianapolis under Captain McVay, I would like to state our deep resentment and ask: Why is the Navy still out to falsely persecute and defame him?”

Most of the available histories of the Indianapolis sinking — Fatal Voyage, Left for Dead, Out of the Depths, Lost at Sea (there’s also a bad movie starring Nicolas Cage) — focus on the suffering of the crewmen abandoned by a Navy too busy or too disorganized to notice that a heavy cruiser had gone missing. The Vincent/Vladic book is, by and large, an update on the Indianapolis story and concludes with the August 2017 discovery of the ship’s remains, now a designated war grave, in the North Philippine Sea, bringing to a close the ship’s eight-decade saga.

“For the families of the lost at sea,” write Vincent and Vladic, “the news stirred high emotions, bringing back memories many had sealed away for decades. After nearly three-quarters of a century, children, nieces, nephews, and grandchildren were finding the peace that their parents and grandparents had sought for so many years.”

This cathartic effect notwithstanding, one thing is certain: With only 19 Indianapolis survivors still living, the finger-pointing and recriminations will soon enough cease to matter. OH

Stephen E. Smith is a retired professor and the author of seven books of poetry and prose. He’s the recipient of the Poetry Northwest Young Poet’s Prize, the Zoe Kincaid Brockman Prize for poetry and four North Carolina Press awards.