The Play Was the Thing

For amateur golfer Dale Morey, competition was all

By Bill Fields • Photographs from Doug Morey & David Williams

Dale Morey drove the highways of the Southeast for decades, logging tens of thousands miles a year, from the 1960s through the’80s, to and from his longtime High Point home. His full-size sedan — a Cadillac or Mercedes, but blue, always blue, his favorite color, regardless of make — was fitted with custom shocks to cushion the ride. He was a furniture hardware salesman traveling with product, and the samples were as heavy as his foot.

“He liked to drive fast,” recalls Morey’s son, Doug. “The highway patrolmen knew him on a first-name basis. Dad got his share of tickets.”

Regardless of where Morey was going to or coming from on a business trip, he usually had additional cargo in the trunk: golf clubs that he used to become one of the finest amateurs ever to call the Old North State home. Morey’s game traveled well and it aged gracefully.

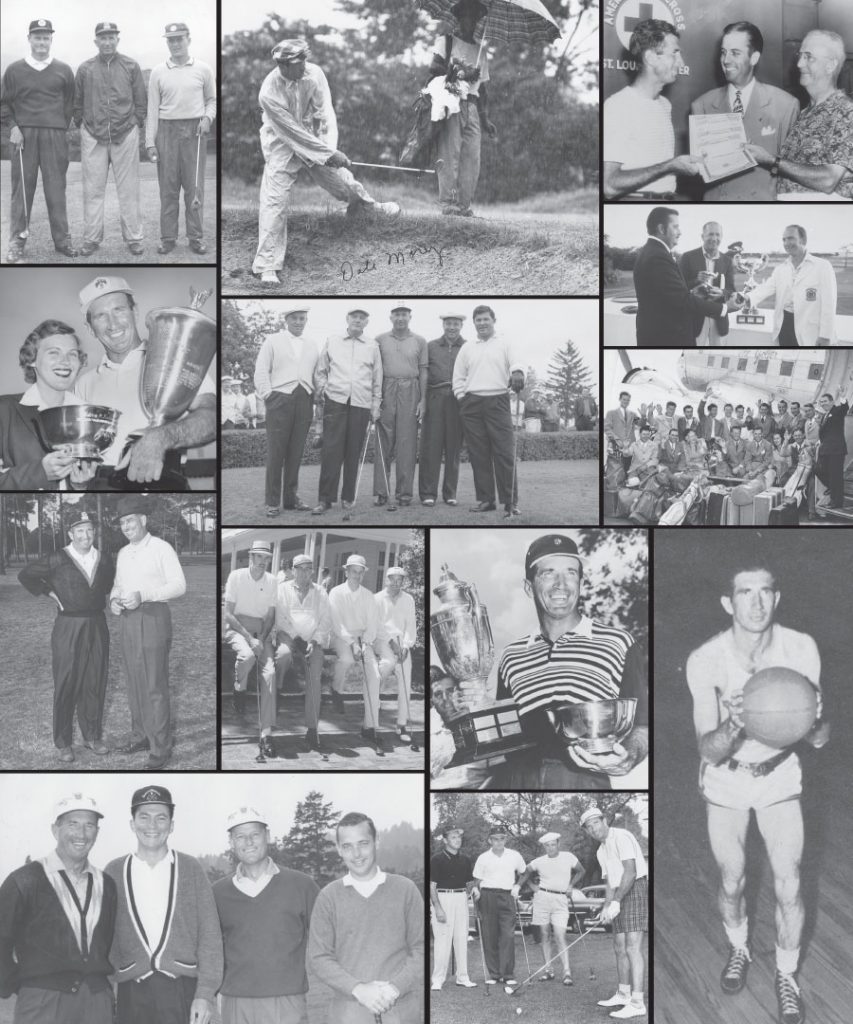

“He’s a real player,” Ben Crenshaw noted after being grouped with Morey in the 1973 Western Amateur. It had been two decades since Morey won the prestigious event — and six other titles in the same year that he was runner-up to Gene Littler in the U.S. Amateur. Morey was 54 at the time, yet not giving an inch to golfers less than half his age.

As Gary Koch, a Crenshaw contemporary who would go on to have a successful PGA Tour career of his own, says, “If you were going to an amateur event in that period and saw Dale Morey was in the field, you knew he was going to be someone tough to beat. He was a serious competitor, and he knew how to play golf.”

There was certainly no doubt about that, not with a golf record good enough to earn him induction into the sports and golf halls of fame in both his native state of Indiana and his adopted home of nearly 50 years, North Carolina.

With 2018 being the 100th anniversary of Morey’s birth it is a perfect time to remember this wonderful golfer, who lived in High Point for many years until his death in 2002 at age 83.

Morey was no stranger to Greensboro’s PGA Tour stop, having played in it seven times from 1961–1972. He shot a final-round 66 in 1968 to tie for 29th. The following spring, when he was 50, he opened with a 66 to share the first-round lead with Littler and Gordon Jones, turning back the clock in the manner of eight-time Greater Greensboro Open champion Sam Snead, who won his last GGO in 1965 at the still-record age of 52.

There was a time early in Morey’s life when sports, not sales, was his job. After an All-American career in basketball and golf at Louisiana State University from 1939–42, Morey turned professional and tried his hand on the golf circuit intermittently for a few years. He played in 38 tour events with three top-10 finishes in his lifetime.

His best finish was seventh in the Montgomery [Alabama] Invitational in the fall of 1946, but that week at Beauvoir Club was telling for Morey, who shot a first-round 64 but still trailed Jim Ferrier’s 62 and Ky Laffoon’s 63. Believing that he didn’t have the talent to make a good living in an era when purses were meager, Morey worked club-pro positions in Illinois, Missouri and Kentucky for a couple of years. During winters, he played pro basketball for the Anderson [Indiana] Packers.

“I played forward in college and guard in the pros,” the 6-foot-1 Morey told a reporter in 1982. “Nowadays, I’d play waterboy.”

Those barnstorming days of games in cozy gymnasiums were a far cry from the ramped-up contests of the modern National Basketball Association. Morey loved to recall a player with skills beyond the hardwood. “One player was a ventriloquist who was good for at least two points a game,” says Morey’s son. “He’d go under the basket and throw his voice and then be open for a layup.”

It was no surprise that Morey got involved in basketball growing up in Martinsville, Indiana, a small town in the central part of the Hoosier State between Indianapolis and Bloomington. When John Wooden was 14, in 1924, he moved to the same neighborhood in Martinsville where Morey and his single mother, Bess, lived. Eight years older, Wooden — a star player at Martinsville High School and Purdue University before his legendary coaching career at UCLA — befriended the younger, promising Morey whose growth spurt came late.

“Dad’s parents separated when he was little and he grew up pretty poor,” Doug Morey says. “He lived across the street from John Wooden. They’d let him play in pickup games until some of the bigger guys showed up. Wooden taught him that the little guy’s got to work harder.”

Perhaps that was his way of paying it forward, as Martha Morey, Dale’s widow explains: “Wooden was kind of a mentor to him. Somebody had been real good to Wooden, and he was kind of passing that help along. He took Dale under his wing and saw to it that he got a basketball scholarship to LSU.”

Basketball led Morey to golf, his prep coach urging him to caddie to strengthen his legs for the season. Morey took to the game, soon developing a particularly deft touch on and around the greens — uncanny skills that were the foundation of his game from his junior days to his senior years.

“Dale Morey, the Martinsville High School champion, did away with medalist Chick Yarborough, of Washington, when his putter was a magic wand,” The Indianapolis News reported in its July 28, 1937, account of the opening round in the Indiana Junior Amateur. “The margin was 4 and 3 and Dale used only twenty-two putts for the fifteen holes.”

One Indiana sportswriter dubbed the rising young golf sensation a “Hoosier Links Houdini” because he scrambled so well. Morey referred to his wedge as his “dead iron,” so frequently did he chip and pitch the ball “dead to the pin” to save par even when his ball-striking let him down.

Tommy Langley, 86, a High Point investment adviser, played regularly on weekends with Morey for a quarter century. “I called him ‘Dandy Boy,’ and he called me ‘Tommy Boy,’” Langley remembers. Langley, who was graced with an elegant, high, beautiful golf swing, remembers Morey’s swing as “sort of flat but effective,” a lethal combination with his chipping and putting skills. “He said, ‘Tommy Boy,’ I can’t be pretty like you, I just have to get the ball in the hole,’” Langley continues. “Dale broke his wrists and hit his putts a little bit right to left, hooked them. He chipped the same way, his right hand coming over the top a little bit. He had this magic touch.”

Applying to the USGA for his amateur reinstatement in 1947, Morey couldn’t compete in anything for two years but quickly made up for lost time by winning the Southern Amateur in 1950 (he would win it again 14 years later). In the 1953 U.S. Amateur at Oklahoma City Golf & Country Club, Morey battled a cold and was “gobbling vitamin pills and guzzling orange juice,” according to the Associated Press’s Will Grimsley, but it didn’t weaken his tenacity. Trailing 2-down to Littler after 33 holes of the 36-hole final, Morey, who had defeated Bill Campbell in the fourth round, birdied the next two holes to draw even. Morey’s rally forced Littler to sink a lengthy birdie putt on the 36th hole to win the championship.

“Dad cleaned up for the presentation, putting on a nice shirt and sport coat,” Doug Morey says. “Then he saw Littler was still in his game outfit. He asked Littler, who was younger and just out of the Navy, if he was going to put on a coat. Littler said he didn’t have one. Dad said, ‘Wait a minute,’ and went back into the locker room and put on his game outfit, and they went out for the ceremony looking the same. That kind of sums him up. He was very much like that.”

Gentlemanly but not necessarily gentle in the heat of a tournament. Koch, who contended with Morey at the 1971 Southern Amateur at the Country Club of North Carolina when he was 18 and Morey was 52, remembers a steely competitor. “He was old school, and I don’t mean that in a derogatory way,” Koch says. “But he was not above trying to make you feel uncomfortable. There wasn’t a lot of chitchat if you were grouped with Dale. He was a tough guy.”

Langley calls Morey “the strongest, most able competitor you ever saw in your life” who had a strong will and “could be very confrontational” with someone he thought was attempting to bend the rules. To Morey, who won the Indiana Open and Amateur titles four times apiece as a young man, golf wasn’t about attention or accolades or awards even though golf brought him plenty of each. The play — serious, give-it-all-you-have play — was the thing.

“It was all about the competition,” Martha affirms, reluctantly revealing that her late husband “once even put some of those big ole trophies out for the trash.”

During an era in which golf equipment wasn’t nearly as forgiving — balls not as lively, club heads smaller and shafts heavier — Morey thrived on competition, whether against young men headed to the tour or his senior peers. The two-time U.S. Walker Cup team member played in the Masters and U.S. Open multiple times and had striking longevity in the U.S. Amateur, finishing ninth in 1972 at age 53. Five years later, at 58, he beat a 22-year-old in the first round.

Well past the age most golfers weren’t doing much except filling out a field, Morey won the 1967 Carolinas Amateur and North Carolina Open and the 1968 and ’69 North Carolina Amateur. Those victories set the stage for a fabulous senior career that would earn him the distinction as senior golfer of the 1970s from Golf Digest.

Morey won the U.S. Senior Amateur in 1974 and 1977 and was dominant close to home. He captured the Carolinas Golf Association Senior Amateur seven times and CGA Senior Four-Ball on 12 occasions. In eight of these he teamed up with close friend Harry Welch of Salisbury.

“Dale stayed trim and was a just a rigid, tough competitor,” Tommy Langley says. “He intimidated people in senior golf because he was in such good shape.”

The man who jogged with ankle weights (he ran two miles each morning during his first national senior win) and regularly exercised at the High Point YMCA, stayed motivated to succeed for a long time. “It’s hard to keep up the desire to win,” Morey said, explaining his competitive longevity to a reporter for The Tampa Tribune in 1978. “A lot of the guys say they’re out here for fun. If you want fun, you can go to the beach.”

Morey approached his work with the same dedication, often leaving home before sunrise to drive to a sales call. “He packed a lot into a day,” Martha says. “That’s the way he was. Going into some of those purchasing agents’ offices, in Virginia or wherever it might be, he’d be there before they got to work. He’d be waiting on them.” Her husband’s energy and enthusiasm along with a personality suited to sales was a potent combination. “He was very much a people person,” says son Doug, “whistling, a good guy, very well-mannered.”

Being a talented golfer certainly didn’t hurt Morey’s sales efforts either, his reputation on the course helping his career away from it. “He was very well-known and very well-respected,” says David Williams, who worked with Morey during the 1980s. “Dale was fortunate because he played customer golf and was known by the presidents of all the companies. He was able to sell from the top down rather than most of us who had to sell from the bottom up.”

But golf and business aren’t always top of mind when Morey’s children reminisce about their father. Doug remembers how impossibly tough it was to beat his dad’s underhanded free throw touch in the driveway. To Morey’s daughter, Maureen Schirtzinger, he was a man who loved gadgets, an early adopter of car telephones nearly a half century ago. “It was huge and had no range, but he had one,” says Maureen, who was also the first kid on her block to have a radio that mounted on her bike’s handlebars.

“From a kid’s perspective, his golf seemed very normal,” Maureen says. “I probably was older before I realized how good he was. It wasn’t like it was us or golf. He would come to father-daughter school days. I don’t think I ever saw him not be friendly or not talk to someone.”

Once when Maureen was a young girl, her father returned from an out-of-town drive with something other than a sales order, speeding ticket or golf clubs in the car. “It was a giant stuffed rabbit, 4 or 5 feet tall. He had it belted in on the front seat,” she recalls, unsure of whether her dad won the plush toy by waving his magic wand of a putter, or with the Morey magic touch, simply pulled it out of a hat. OH

North Carolina native Bill Fields has written about golf since the mid-1980s and has won multiple awards from the Golf Writers Association of America.