How the master of the short story became O.Henry

By Bill Case

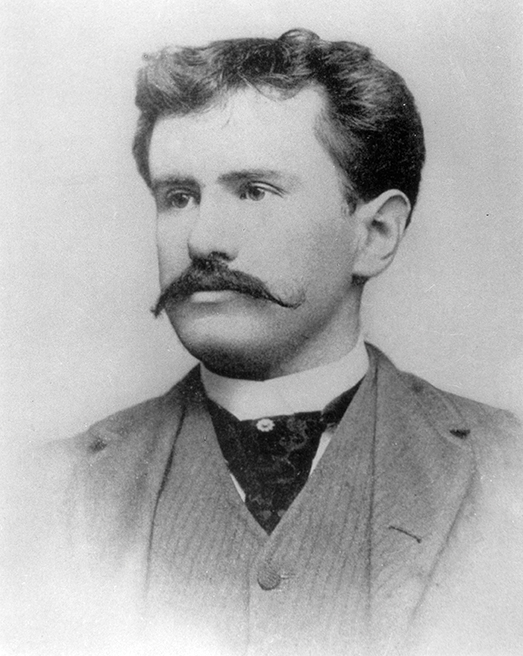

With his life in shambles, Will Porter — later to become known as O.Henry — boarded a train at the International–Great Northern depot in Austin, Texas on April 22, 1898, heading to prison in faraway Columbus, Ohio, to serve a five-year sentence for embezzlement. But that was not the only difficulty that the 35-year-old former bank teller and talented, though relatively unknown, writer and cartoonist confronted. Athol, the young Austin woman whom he married in 1887, had died the previous summer of tuberculosis — the same disease that had taken her father and Porter’s mother. This meant Porter’s 8-year-old daughter Margaret would have no parent at her side for the foreseeable future.

With Deputy Marshal Musgrave alongside guarding him, Porter had ample time during the three-day journey north to reflect upon the events beginning in 1882 that had led him from home in Greensboro to Texas and now to prison. While employed as a drugstore clerk in the downtown Greensboro pharmacy operated by his uncle Clark Porter, William Sydney Porter had developed an incessant, racking cough. At the time, the drugstore was a popular meeting place for city businessmen to gather and kibitz about goings-on in the community. One frequenter was Dr. James Hall, who took note of 19-year-old Porter’s persistent cough. Alarmed that the young man might be in danger of contracting tuberculosis, Hall urged Porter to accompany him during the doctor’s upcoming Texas vacation to visit two sons, Lee, a celebrated Texas Ranger, and Dick. The Hall brothers managed a 250,000-acre livestock ranch in south Texas. Dr. Hall reckoned a sojourn on the ranch would rid Porter of his hacking cough. Porter agreed to give Texas a try.

The doctor was right. Once on the Hall ranch, Porter’s health was rejuvenated. For the next two years, he immersed himself in the ranch’s work, relishing his role as a hand for the Halls, riding horses, sheepherding and fixing fences. But inevitably longing for more social interaction, particularly with members of the opposite sex, 21-year-old Porter decided to forego the prairie and try city life in Austin.

Once there, he cycled through several jobs: drugstore clerk, real estate company bookkeeper and draftsman for the government land office. The social Porter became a man-about-town, contributing his tenor voice to the “Hill City Quartet,” and hobnobbing with Austin’s younger set in the city’s saloons and gambling parlors. He courted several women, but it was Athol who caught his eye, and they married in 1887. It was she who now encouraged him to embrace his budding literary talent. Porter began composing short vignettes of Texas life and selling them to Eastern newspapers for modest sums.

But during his Austin days, Porter’s writing income couldn’t support a family — which by 1889 included Margaret. So when in 1891, an opening occurred for a teller at the First National Bank of Austin, Porter applied and landed the job. His lenient bosses at the bank let Porter continue moonlighting with his writing. Looking for an outlet for his talent, he purchased a failing Austin weekly newspaper, The Iconoclast, in 1895. Rechristening it The Rolling Stone, Porter served as a one-man band for the rag, responsible for writing, editing and drawing cartoons. Soon, he received recognition in local circles for his chatty jocular stories that often spoofed local figures. After a short period of being an attentive husband, Porter renewed what would become a lifelong habit of whiling away the nights in saloons and back alleys. He rationalized his behavior to Athol by claiming Austin’s diverse cast of characters provided fodder for his stories.

Porter cared little for his work at First National. It was simply a means to an end. His involvement with the newspaper he acquired, The Rolling Stone, constituted his real passion. Sensing he was on the threshold of self-sufficiency, he quit the bank in October 1894 to devote full time to the publication. But despite its artistic success, the paper capsized in a sea of red ink in April 1895 and Porter was left adrift without gainful employment. In October, the editor of the Houston Post offered the struggling Porter a life raft: a position as a “special writer” at the modest rate of $15 a week. With no other prospects, Porter pulled up stakes and relocated to Houston. Athol and Margaret temporarily remained in Austin with Athol’s mother and stepfather, Mr. and Mrs. P.G. Roach, until The Post upped Porter’s pay. But upon finally arriving in Houston, Athol began to suffer the early symptoms of her tubercular condition. Ultimately, she and Margaret returned to Austin.

Meanwhile, a gathering storm forced Porter to take a leave of absence from The Post. Prompted by relentless Federal Bank Examiner B.F. Gray, a grand jury had handed down a four-count indictment in February 1896 against Porter, claiming he had embezzled a total of $4,702.94 while employed as First National’s teller. To those familiar with First National’s loose banking practices, it seemed unfair for the government to target Porter for the shortages. Routinely, the bank’s officers dipped into the till themselves, withdrawing cash without leaving IOUs. Bank policy had permitted overdrafts to these same officers. While Porter had been sloppy, too trusting of the bank officials and oft distracted by his duties at The Rolling Stone, his friends could not fathom he would be consciously dishonest.

As Will Porter reflected on these matters while riding the rails to the Ohio Penitentiary, he undoubtedly recalled the inexplicable decision he made on another fateful railroad journey two years before. On June 22, 1896, he was aboard an evening train steaming out of Houston to Austin for the start of his federal criminal trial. At some point after boarding the train, Porter changed directions and fled from justice. He disembarked the train in Hempstead 50 miles out of Houston and boarded another to New Orleans, where he would live as a fugitive for six months, picking up occasional assignments from local newspapers under the assumed name of “Shirley Worth.” In December, Porter grew concerned that authorities might be getting wind of his whereabouts, so he hightailed it to Honduras, a country having no extradition treaty with the United States.

Will Porter’s many biographers have offered an assortment of views as to why Porter fled — especially when it seemed he had a defensible case. One observer opined that Porter chose exile because he figured his bosses, who were well-known in the community, would be accusing him of wrongdoing to avoid being charged themselves. Another offered that Porter “could not measure up to the overpowering strain upon his sensitive nature.” A perhaps overly sympathetic writer asserted that “it was not cowardice that motivated his actions. . . It was the call of a new start in life, the challenge of a novel and romantic career.” Other historians say Porter believed (misguidedly) that if he successfully evaded prosecution by remaining outside the country for three years, the statute of limitations would protect him from conviction.

With her tubercular symptoms temporarily in remission, the loyal Athol enrolled in an Austin business school, arming herself with employable skills. But after her condition suddenly, and gravely, worsened, the Roaches contacted Porter, who came back to Austin, where he voluntarily appeared in court.

Federal prosecutor R. U. Culberson harbored misgivings about the strength of his case against Porter. But unceasing pressure from zealous Bank Examiner Gray had forced the prosecutor to press forward. Culberson did agree to a lengthy postponement, allowing Porter to attend to his wife during her final months. Athol died on July 25th at age 29. To escape his grief and the interminable agony of waiting for trial, Porter turned to his writing. Working in a room above the Roaches’s Sixth Street store, he wrote “An Afternoon Miracle,” which he sold to the S.S. McClure Syndicate. This first freelance sale of a short story was the one sliver of good news Will Porter received while awaiting his reckoning in federal court.

By the time the trial finally commenced on February 15, 1898, the charges had been pared down to two transactions involving a missing $554.08. But Porter’s chances of escaping conviction were marred by his detachment from the proceedings. He declined to review the bank statements with his lawyers. Perhaps feeling he was ruined regardless of the jury’s verdict, Porter sat listlessly at the defense table, seemingly indifferent to the damning testimony being offered. Porter urged his friends not to attend. He failed to testify in his own behalf, thereby leaving unrebutted the prosecution’s insinuations that Porter had used ill-gotten money from First National to fund his fancy clothes, nighttime revelries and to prop up The Rolling Stone. Still, many historians have concluded Porter likely would have escaped the jury’s forthcoming guilty verdict had he not fled. Porter himself acknowledged later that by doing so, he had “made one fateful mistake at the supreme crisis of . . . [my life], a mistake from which . . . [I] could not recover.”

Notwithstanding the verdict, Porter steadfastly maintained his innocence in correspondence with friends. He wrote Mrs. Roach that “I am absolutely innocent of wrongdoing.” To another friend, he complained that “[t]he guilty man [presumably a bank higher-up], if charged, would take the stand and call me a liar. He is not, as I thought, a man of honor, or he would have kept his word to me and straightened the matter out when I left Texas and the bank.” To another, Porter confided a concern he would be considered an accessory by not reporting another bank official’s wrongful conduct.

But now, as the steel gate of the penitentiary awaited, a paramount concern for Porter was how he was going to support Margaret, now 8, and under the care of the Roaches. While Will Porter may not have been the most dutiful of fathers, there is no doubt he adored Margaret. He would write: “Now I have a daughter, a child of my own blood, bone of my bone. She is my most precious possession.” And Margaret reciprocated this affection. Long after her father’s death, she fondly recalled that their relationship “was never that of father and daughter, but of two good friends . . . We were inseparable playmates and companions until my eighth year and the death of my mother.”

Porter helped plant an idealized vision of himself by going to great lengths to keep Margaret from knowing about his imprisonment. That was going to take some doing since Margaret, an intelligent girl, would most certainly be exposed to gossip concerning her father at school and elsewhere in Austin. So Porter convinced Mrs. Roach to move Margaret to the Nashville, Tennessee, farm of his mother-in-law’s brother, “Uncle Bud.” Margaret was told that her father would be away from home for a prolonged time on business.

Checked into the penitentiary as prisoner number 30664, Porter initially wallowed in despair. It appears he toyed with taking his own life. In letters, he mentioned that “suicides are as common as picnics here.” The chief physician of the prison reported that in his experience he had “never known a man who was so deeply humiliated.”

In spite of his mental anguish, Porter considered his relationship with Margaret a vital lifeline, and he did his best to preserve it, writing her frequently. He apologized for abruptly leaving in his first prison letter to her: “I am so sorry I couldn’t come to tell you goodbye when I left Austin. You know I would have if I could have. I think it’s a shame some men folks have to go away from home to work and stay away so long — don’t you?”

Much of his correspondence sought to reprise the rollicking tomfoolery the father and daughter had experienced while together during better times. “Don’t you remember me?” he teased. “I’m a Brownie, and my name is Aldibirontiphostiphornikophokos.” In another bit of whimsy, he wrote, “If you see a star shoot and say my name seventeen times before it goes out, you will find a diamond ring in the back of the first cow’s foot you see go down the road in a snowstorm while the red roses are blooming on the tomato vines.” He would pen other silliness, asserting in one missive that Easter eggs did not come from rabbits but from eggplants. Porter would promise Margaret that one day soon, he would have the pleasure of reading “Uncle Remus” to her once more.

Meantime, Porter adjusted to prison life. He renewed an acquaintance with train robber Al Jennings, a drinking buddy when both were hiding in Honduras. Jennings became his best friend in the pen.

Porter also managed to snag the position of night druggist at the prison hospital. In the course of his four years of drugstore clerking in Greensboro, he had become licensed as a North Carolina pharmacist. That background had come in handy in helping Porter land one of the prison’s least backbreaking jobs. He subsequently earned the thankfulness of the warden when he saved his life by speedily mixing a potion that relieved the effects of an overdose of arsenic that had been inadvertently prescribed by the prison’s doctor. The warden’s gratitude helped Porter obtain a position outside the penitentiary walls as the prison steward’s secretary responsible for nighttime bookkeeping. In this capacity, Porter was allowed to walk the streets of Columbus when not on duty, sleeping in quarters outside the prison with several other lucky “trusties,” including Al Jennings. He and his roommates formed what they termed the “Recluse Club.” Porter would scrounge together enough food in his daily wanderings that he and his fellow “Recluses” were able to dine surreptitiously but sumptuously on Sunday nights — white shirts required!

In better spirits and having more free time, Porter delved back into his writing with a newfound, previously untapped discipline. The prison years proved vital to Porter’s subsequent success as it was during his incarceration that he mastered the short story genre and developed his personal trademark of unexpected story endings. Biographer Gerald Langford in his book Alias O.Henry notes that many of his subject’s 14 prison stories involve, “the vindication of a character who has in some way forfeited his claim of respectability or even integrity.”

Through an elaborate conduit designed to hide the fact he was writing from prison, Porter began peddling his pieces under the name “Sydney Porter” (his given name was William Sidney Porter) — a rather thin alias for someone trying to hide his past. Porter then tried other names on for size, but O.Henry was the one that ultimately stuck. There are various tales as to how he chose the name, including : (1) he picked it from a society column’s list of attendees at a ball in New Orleans; (2) a friend’s cat named Henry would only respond to “O Henry!”; and (3) the “OH” initials were also the first two letters of Ohio. Biographers can’t agree as to what caused him to select this particular alias.

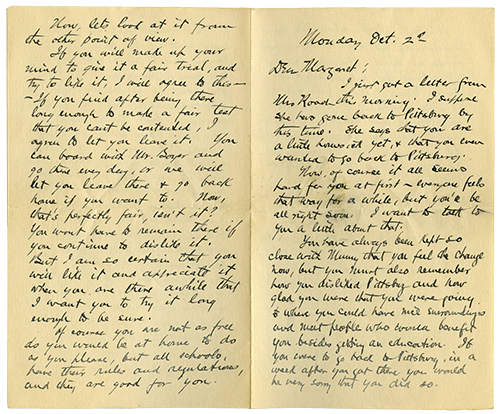

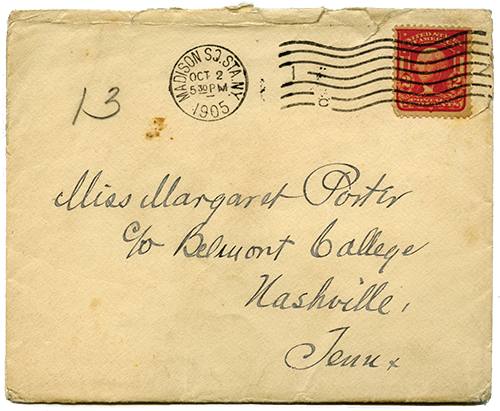

Despite the improvement of prison life, the infrequency of Margaret’s letters cut him to the quick. He worried the young girl was forgetting him, and he beseeched her to reply to his correspondence. In November 1898 he lightly scolded, “I guess you’d rather ride the pony than write about him, wouldn’t you? But you know I’m always so glad to get a letter from you even if it’s only a teentsy weentsy one.” Likewise, in February 1900, he wrote Margaret, now on the brink of becoming a teenager, the following: “I got a letter from you in the last century, and a letter once every hundred years is not very often.”

Meanwhile, the Roaches moved to Pittsburgh, where Mr. Roach took up the ownership and management of a second-rate hotel. Granddaughter Margaret came with them. Always trying to draw Margaret out, Porter inquired, “Tell me something about Pittsburgh and what you have seen of it. Have they any nice parks where you can go or is it all made of houses and bricks?” While Porter promised the Roaches he would reimburse them for their expenses in taking care of and schooling Margaret, his propensity for allowing money to slip through his fingers, often giving it away, made it impossible for him to fully catch up even after his later financial success.

An exemplary prisoner, Porter’s term was shortened and his release scheduled for July 24, 1901. Excited about the prospect of reuniting with his daughter, he wrote, “We haven’t gone fishing yet. Well there is only one month till July, and then we’ll go, and no mistake.”

Starting over as an ex-con in Austin was out of the question, and all of Porter’s relatives in Greensboro were deceased. Of course, he had virtually no money, so once freed, his only real option was to stay with the Roaches and Margaret in Pittsburgh, where he picked up freelance work with the Pittsburgh Dispatch. But not long after arriving, he moved alone to a flat in a rooming house citing the unconventional hours the newspaper required. It must have been hard on Margaret to have her father vacate so soon after his being long apart from her. She would later try to put the best face on the stop-start nature of their relationship. “We would just begin to emerge from an ever-increasing reserve that seemed to beset us both,” she wrote, “when time would come to part again.”

Porter expressed to Jennings his intense dislike for Pittsburgh, writing that, “Columbus people [presumably the prisoners] are models of chivalry compared with them [Pittsburgh residents].” His antipathy for the city aside, “O.Henry” successfully churned out a number of short stories while in residence, which increasingly began appearing in several New York–based magazines — most notably Ainslee’s, whose editor, Gilman Hall, suggested in 1902 that Porter relocate to New York. After negotiating a $200 advance from the magazine, Porter headed to the city where his dreams of making it big were on the threshold of coming true.

Porter’s arrival in New York proved to be perfectly timed. Public demand for good short story writing in the city’s numerous literary magazines had risen to a fever-pitch. Once editors got wind of Porter’s knack for the genre, they knocked down his apartment door in efforts to publish his stories, now all under the pen name of O.Henry. And even though he was prone to missing deadlines, Cosmopolitan, Harper’s, McClure’s and Munsey’s magazines — and the New York World newspaper — remained at his beck and call. When absolutely forced to, he could churn out a story with astonishing speed. His tour de force, “The Gift of the Magi,” was conceived and written in longhand in only two hours after Porter discovered he had forgotten an obligation to the Sunday World to produce a Christmas story.

He wrote not for fame — that might cause the revelation of his dark secret — but for financial reward. He once explained that, “[w]riting is my business. It is my way of getting money to pay room rent, to buy food and clothes and Pilsener. I write for no other purpose.” But Porter seamlessly mixed his business with pleasure by roaming the “New York Tenderloin” long into the night, observing the escapades of both the high hats and dregs of the city, deriving potential story lines from these varied experiences. An incorrigible ladies’ man, he took particular delight in cajoling young shopgirls into joining him for dinner. For the price of a planked steak, he would urge the women to relate their troubles. Several stories Porter penned during his New York days involve the travails of shopgirls, no doubt gleaned from these dual-purpose encounters. In addition to his New York–based stories, Porter wrote others informed from experiences and people he encountered in Texas, Honduras and in jail.

O.Henry never quite managed to turn out a novel as several publishers urged, but collections of his short stories in such volumes as Cabbages and Kings and The Four Million became runaway best sellers. Suddenly he was being compared to the likes of Dickens and Robert Louis Stevenson. Watson’s Magazine’s review of The Four Million summed up what many reviewers were beginning to realize: “In word limit all the stories are shorter than the average magazine story, yet it would be difficult to find as much observation and insight compacted in the short stories of any fictionist today.”

But Porter ducked away from all the plaudits. One of his editors, Robert H. Davis, remarked, “Porter fled from publicity like mist before the gale . . . shrank from the extended hands of strangers . . . and avoided conversations about himself.” On holidays from Ward-Belmont School in Nashville, Tennessee, Margaret would occasionally visit her father in New York, but Porter would keep the visits short. While Margaret may still have been in the dark, every editor in New York knew of Porter’s secret by 1907. Nonetheless, Porter kept trying to hide the secret that was no longer much of one — at least to insiders — until the end of his days.

Unfortunately for Porter, the end of his days were not far distant. Ill health began to dog him around 1907. Whether from staying out all night drinking copious amounts of whiskey or contracting some unexplained sickness, he found himself in a perpetual state of malaise. His deteriorating health may explain how he came to lean on a woman from his Greensboro youth. As a teen, Porter had been periodically smitten with an Asheville girl who was summering in Greensboro with relatives. Sara Coleman had faded out of Porter’s life once he moved to Texas. Suspecting that Will Porter and O.Henry were one and the same, she wrote to him in 1905, and a mutual correspondence ensued. The writings became more intimate as time went by, and Sara eventually visited him in New York in September 1907. Before she returned home, Porter had proposed marriage. Before she responded, he haltingly wrote her and revealed his problematic past. She accepted his proposal anyway. They were married in Asheville two months later. Porter had the best of intentions to reform his late night ramblings. “I’ve had all the cheap bohemia that I want,” he told a friend “It’s for the clean, merry life . . .”

But the marriage seemed less a romantic union than a dependent one, with Sara filling more of a mothering and nursing role. She convinced her husband to move out to Long Island, where he presumably would not be tempted to partake of the saloon life. Margaret, now an aspiring writer and winding up her education at a girls’ school in New Jersey, would be able to spend her summers with the newlyweds. Inevitably, Porter chafed at the peacefulness of his surroundings, and his wife’s unceasing efforts to get him to mend his ways. Like a moth to the flame, he was ultimately lured back to the bright lights of the city. Bearing little acrimony, the couple separated, with Sara moving back to Asheville.

Plunging back into the city’s nightlife doomed any chance of restoring Porter’s health. By midsummer of 1909, he was too sick to work and he reluctantly decamped to Asheville where Sara checked him into a sanitarium. But once feeling better, Porter again could not resist returning to New York. His condition promptly regressed. At the peak of his fame, Porter, 47, found himself alone with no family alongside at the city’s Polyclinic Hospital, where he had been diagnosed with kidney failure, cirrhosis of the liver and diabetes. On Saturday, June 5, 1910, a nurse stopped by Will Porter’s room at midnight to turn off the light. “Turn on the light,” he pleaded. “I’m afraid to go home in the dark.” This served as O.Henry’s personal surprise twist to his own ending. He died later that morning.

His long-suffering widow, Sara Coleman Porter, lived until 1959, penning two books herself, and keeping O.Henry’s literary career in the public eye. As for Margaret, she only learned about her father’s criminal past several years after his death. She had a short-lived marriage to Oscar Cesare, a Swedish cartoonist and associate of her father’s in New York, and an undistinguished a literary career of her own. Ultimately she succumbed to tuberculosis, like so many members of her family. She died on May 9, 1927 having married her caregiver, Guy Sartin, just three days before. Sartin would then become caretaker of Margaret’s personal effects, including letters from the man once known as Will, “Shirley Worth,” Prisoner No. 30664, the Brownie Aldibirontiphostiphornikophokos, Sydney Porter . . . and to the world, O.Henry. OH

Bill Case, a transplanted Ohioan, moved to North Carolina three years ago. Combining his love of history with research skills honed as a litigation attorney, Bill is now a regular writer of historical articles for PineStraw magazine.

O.Henry-bilia

Howard Sartin, Guy’s son, donated his inherited collection of O.Henry letters to the Greensboro History Museum, as did other benefactors including E. M. Oettinger, Carl Prickett Paul Clarkson, and the Porter and Beall families of Greensboro. The GMH, along with the Greensboro Public Library and Greensboro’s News & Record, became faithful repositories of O.Henry — related correspondence, original magazine stories and other materials. Through a joint project of the GHM and the library, spearheaded by Brad Foley (now the librarian for Randolph County in Asheboro), many of these letters and documents became available online in 2005. More recently, GHM and UNCG have teamed up to place these materials onto UNCG’s Digital Collection, where they can be easily enlarged and downloaded at libcdm1.uncg.edu/cdm/ohenrypapers/. Word searches of transcripts will also be possible, making the O.Henry documents more easily accessible to the public.

Photographs courtesy of Greensboro History Museum