Once a preferred stop on the legendary R&B Chitlin’ Circuit, The Historic Magnolia House reclaims the glory of its Green Book days — and then some

By Grant Britt

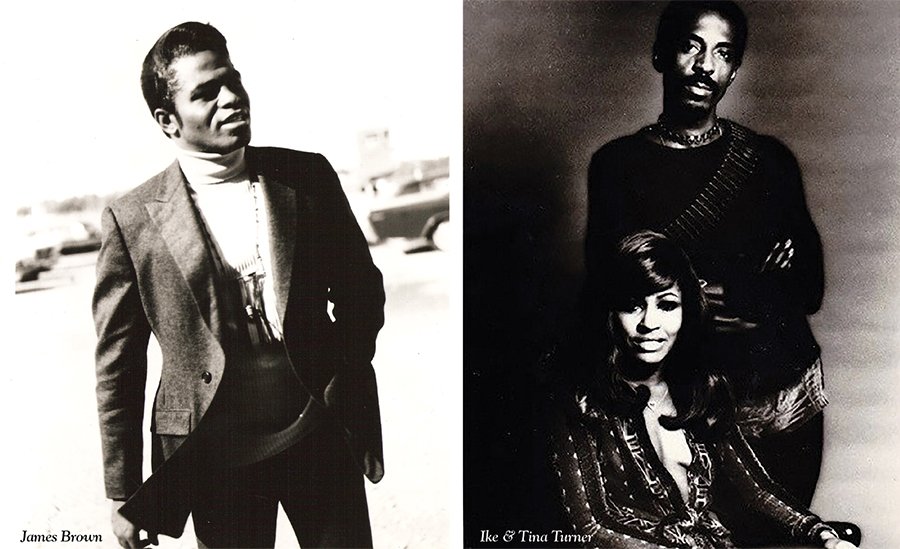

Once upon a time, there was a magical musical pathway that wound through the Piedmont, carrying deliverers of soul on their appointed rounds. African-American singers and musicians toured the country on a beltway that connected the East Coast to a string of clubs specializing in R&B and soul. The pathway was called the Chitlin’ Circuit, named after a stinky comfort food made from a pig’s large intestine, initially favored by folks who by economic necessity had to use every part of the hog but the squeal. James Brown spotlit some of the Chitlin’ Circuit’s whistle stops including Raleigh, North Carolina, on his 1961 version of “Night Train,” recorded at one of the Circuit’s top venues, the Apollo Theater in New York City. Other notable stops along the way included The Howard Theatre in D.C., the Royal Peacock in Atlanta, Richmond’s Hippodrome Theater, and The Ritz Theatre in Jacksonville, Florida. Greensboro was an important stop along the way as well, with The Ritz and the Carlotta Club providing a showplace for big names like Brown and Joe Tex.

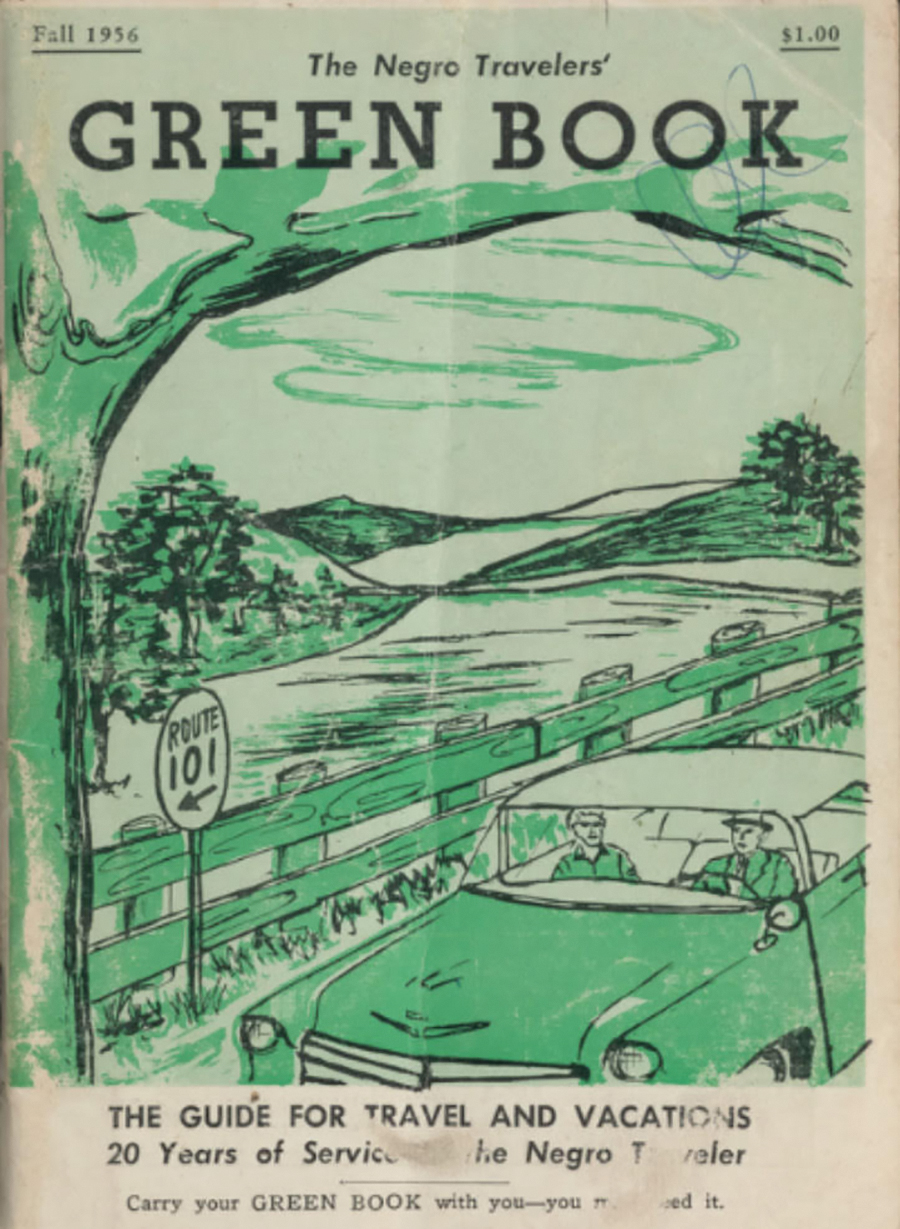

Getting there was the easy part. But finding a place to eat,or more important a place to stay, was a problem for black artists for decades in those preintegration days. In 1936, New York City mailman Victor Hugo Green compiled a coast-to-coast compendium of establishments that catered to African- American travelers. The Negro Motorist Green Book, (inspiration for the current Oscar-nominated film, Green Book) became the Negro Travelers’ Green Book in the early ’50s when it expanded its coverage to Mexico, Canada and part of the Caribbean. It provided names and addresses of restaurants, bars and hotels that would let road-weary African-Americans eat, drink and rest with dignity and in comfort. The 1939 edition, expanded from early editions only listing New York destinations, shows a variety of establishments in Greensboro that welcomed black travelers, including the Legion club, listed under hotels on 829 East Market Street and the Travelers Inn, also on East Market, and several private “Tourist” homes on East Market: T Daniels at 912 East Market, Mrs. Evans at 906, Mrs. Lewis at 829, as well as the Paramount Tavern at 907 East Market.

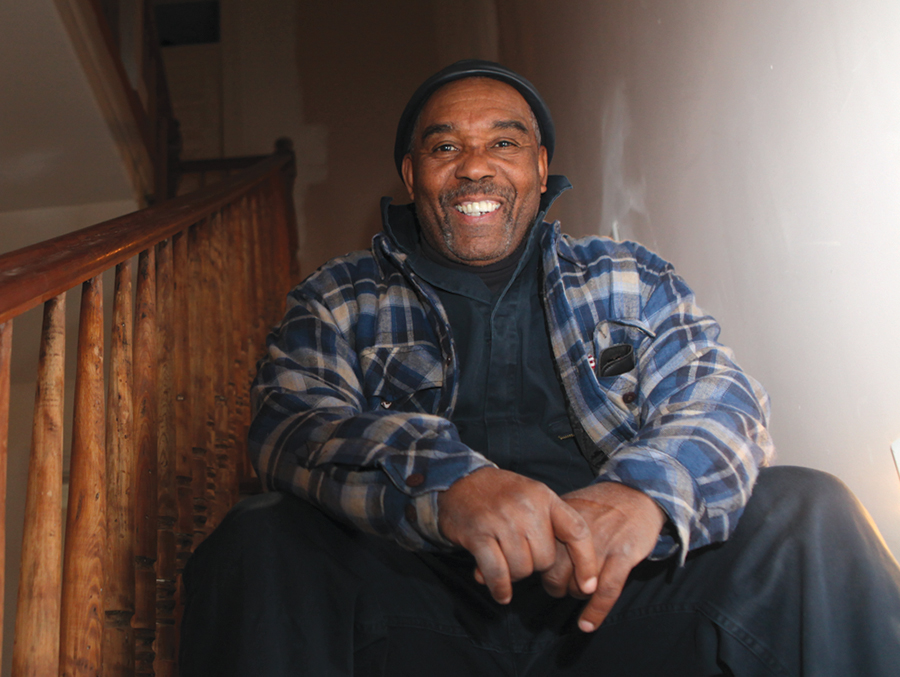

But one of Greensboro’s most prestigious Chitlin’ Circuit rest stops wouldn’t show up in the Green Book till 1955. The Magnolia House Motel was built by Daniel D.Debutts in 1889 at the corner of Gorrell and Plott streets in the Southside community. The 5,000- square-foot Victorian was a showplace even back then with its wraparound porch and imposing façade with five chimneys. The house began its career as a lodging destination when the Gist Family bought the property in 1949, catering to a Who’s Who of Chitlin’ Circuiters including James Brown, Ray Charles and Hank Ballard and the Midnighters. State legislator Herman Gist and his wife, Grace, inherited the property from their parents and ran it as a motel for several years. But the house fell into disrepair in the ’70s and remained a decaying shadow of its former self till 1996, when neighbor Sam Pass, who lives right around the corner on Martin street, saw the property up for sale. “It was in pretty bad demise. The roof was caving in, she [Grace Gist] couldn’t keep the street people out of here.” Pass was so determined to own the property that he ripped the for sale sign out of the ground and hid it until he could make Gist an offer, which she accepted.“ I remember the big marquee in the front yard,” he recalls. “It always said ‘NoVacancy.’ Magnolia House has been in existence as long as my generation has been in existence.”

“I noticed Magnolia House when I was a kid,” Pass continues, recalling that his older brother Bobby, a music promoter, brought his 13-year-old sibling to the house and introduced him to Joe Tex, who was playing in town. Pass met Tex on the front porch and remembers him as being very cordial to his tongue-tied, star-struck younger self. Pass’s brother introduced him to several other of the celebs staying at the Magnolia, and Pass says he heard stories of Tex and Brown playing baseball with the neighborhood children. “We knew about the Magnolia House even before then.” Pass says. “This was the first black hotel. When they couldn’t stay anywhere else, they stayed here.”

Greensboro had several musical hot spots from the mid-’40s through the ’60s. The black-owned El Rocco club on Market Street in Greensboro also brought in big names in the ‘50s including Jackie Wilson and James Brown, as well as Otis Redding. It also served the best fried chicken in town. “James Brown used to come to El Rocco,” Pass recalls. “My cousin George Simms was a drummer. He [James] used to come to my grandmother’s house and beg her to let George play for him. ‘I’ll keep him outta trouble, Miz Pass,’” he remembers Brown promising.

“El Rocco was something like in New York,” says Chic Carter, former pitcher for the Winston-Salem Pond Giants, a Negro League team in the 1950s. Evoking comparisons to Gotham’s famous Apollo Theater and a few others on the Circuit, he adds, “El Rocco had a nice place over there for them to come.”

Although it was a black club, some white visitors were welcome. “I used to take some girls to the El Rocco,” says Greensboro-based shag dancer Larry McCranie, who is white. “One time in the mid-’50s, I took four girls down there and we were the only white folks in there. They were cool girls, they ended up dancing with all the black guys and I danced with black women and we just had a ball. Not too many white kids went over there,” he reminisces, “but occasionally they were invited, the girls could dance, and you could just have a good time.”

McCranie also recalls a tobacco warehouse in Greensboro outside the city limits on South Elm/Eugene Street that hosted big-name acts about every other month. He says he remembers seeing Fats Domino, Lavern Baker, Ruth Brown and Chuck Berry, all on one show. Sheriff’s deputies hired to keep order between the races would put a rope from the front where you entered, all the way up to the middle of the stage. “White folks would go on one side, and black folks would go on the other. Everybody had a little bottle in their pockets, they’d get to drinking when they opened around 8:30 or 9 o’clock,” McCranie says. “Around 11 o’clock, that rope would come down and there was nothing they could do about it. There weren’t that many sheriffs there, and then everybody danced with everybody.”

Pass also heard about the warehouse and mentions another club, the Carlotta, down off Market Street, that was also a popular destination for Chitlin’-esque performers. There was the ABA club off High Street near Ray Warren Homes. “Then there was this little club called the Americana up near Gillepsie Golf Course. My brother used to frequent the place,” Pass says, recounting an anecdote about how older sibling Bobby once introduced their sister Ruth to Ben E. King of “Stand By Me” fame.

The clubs showcased them, but the Magnolia nourished black entertainers and gave a place to rest their weary heads; Pass wanted to pay homage to that tradition as well as preserving a piece of African-American history. He had the house, but now he needed help with the restoration. Retired from FedEx, Pass set up a mobile kitchen outside the property, selling ribs, chicken and fried fish to help raise money to put with $70,000 of his own. The city of Greensboro gave him a community block grant, and he got some help from suppliers impressed with what he was undertaking.

“It’s family basically,” Pass says of his renovation and restoration team. “Me, my wife [Kimberly], my oldest daughter [Natalie Miller] are what’s making this happen. Hopefully I’ll be keeping it in the family. That’s why I restored it.”

On a guided tour of the property, Pass’s pride in the work is evident in his voice as well as in the finished product. “A lot of it I did. But of course, I don’t have the talent to do all of this,” he says. “We didn’t renovate; we totally restored it.” With the help of local cabinetmaker Pete Williams, the Magnolia was gutted to its skeleton. “Then we came back with everything.” The heart pine floor came from the American Tobacco Company Warehouse in Reidsville. The owner of Reidsville’s Tobacco-Pine Reclaimed Timber was so impressed at what Pass was doing, he gave him a steep discount. “The entire house is the same heart pine lumber — the chair rails, the window casings, door casings, all the interior doors,” Pass says. “The baseboards, quarter rounds, the crown moldings, all of that are from heart pine lumber. We did the house the way it was supposed to be done.”

Working from the original blueprints, Pass and family did their best to keep the house true to its original design. “It was important that we leave the outside just like it was, as far as structure was concerned, since the house was on the National Register of Historic Places.” He did do a kitchen makeover, installing a commercial kitchen.

The outside wall was improved on as well to create the majestic stonework that surrounds the house today. Part of the restoration phase was to repair and restore the original 2-foot retaining wall going around the house at 442 Gorrell Street. He approached Mount Airy’s North Carolina Granite Corporation about cutting the granite for the needed repairs. The company ended up donating not only rocks to make repairs but additional granite. “So we were able to repair the wall, but they also gave us 160 tons of it,” he says. “That’s how we got that 7-foot wall built around the house on our property line.”

Architectural Salvage of Greensboro donated period furniture, including a dresser with an impressive pedigree. “We didn’t know what we had until one of our customers for Sunday brunch came through, looked at the piece and said, ‘That looks like Thomas Day furniture,” referring to perhaps North Carolina’s most famous black cabinet maker. “Of course, we researched it, and come to find out, it is.”

Daughter Natalie Pass Miller oversaw the furniture restoration. Pass calls her “an innovative Alpha woman,” which causes Miller to break out into peals of laughter when told of the description. “That is so Sam,” she says, when she can catch her breath. “Oh gosh, I don’t know about that. I’m just trying to help Daddy carry out his vision.”

Miller stepped in about a year ago, bringing back period pieces from Atlanta, where she was living at the time. “This was my very first time driving a U-Haul packed with furniture long distance, praying all the entire way cause I’d never done it before,” she says. “When I pulled up, Dad just happened to be on the porch and you could see the look on his face, like, ‘Is that my kid driving a U-Haul? It is!’”

But her furniture -moving project turned to operational matters once she started probing her father about his intentions for Magnolia House. “Dad’s tone changed to a sad one,” she recalls. Pass’s renovation work was going slowly due to his daily commute to Durham, where he inspects buildings for Duke University in advance of fire marshal visits. His daughter could tell he needed some help. She suggested to him “Dad, why don’t I come in, and let’s work together to see if we can complete this vision that you have now that you’ve done the hard part of restoring the house?”

Pass’s efforts hit another snag when he had a stroke in early November. These days, he is just getting back to work and seeing the changes Miller has implemented. “One of those priorities, including making over the ambiance is, ‘How do we rebuild our brand and reputation and what do we want people to experience when they walk in the house?’” Miller explains. To that end, she’s changed up the serving format of the weekly Sunday Jazz Brunches from a buffet line to family-style dining in the large front room that was once a porch. “The room is cavernous, with 14-foot ceilings,” she says. “The Gist family had renovated it and lowered the ceiling with tile, but I put it back the way it was,” Pass explains. Brunch is served here, with servers bringing out large bowls of sides and entrees to several long trestle tables set end-to-end along the length of the room. “When the Gist family had it as the historic Magnolia House, one of the key things that I noted was that they were really big on creating a sense of family and engagement and unity, bringing that concept to the table,” she says. “And if you think about it, that process exists even in the overnight stay, because not every room had its individual bathroom, so if that doesn’t bring a community together, nothing does,” Miller chuckles. “So moving over to the family-style dining was really created as a part of continuing the legacy of what the motel created.”

The current menu has a number of staples, but introduces a few unique dishes every week. Feedback from guests plays an important role as well, with Magnolia brunch regulars praising the fish and grits, and fried chicken. “We also have a penne pasta in garlic Parmesan sauce with seasonal vegetables that is just to die for,” Miller says of the fare she’s proud to label as comfort food.

But Pass is quick to point out that the family is not calling the new Magnolia House completely a restaurant. “We do have a commercial kitchen in the facility, but it was our intention to open up as a bed and breakfast, and will still be a component because we have the upstairs mostly finished, Pass says. But we haven’t gotten to that point yet.” Right now the focus is on using the house for special events, with bridal showers and baby showers, as well as hosting several local clubs and civic associations parties, including A&T State University Alumni Association events.

Pass has also introduced a series of presentations he calls the Juke Joint Series, dinner and a show, sort of like The Barn Dinner Theatre. “We do tributes to some entertainers that registered here during segregation. First one, we did a tribute to Ray Charles and Ruth Brown, and we just recently did a dinner and a show, a tribute to Gladys Knight and the Pips, and we’re working on a Valentine’s show now. So we do events here, Sunday brunch here every Sunday from 11 til 3:30. And the public will come here for some of the good food that we cook.”

He’s got quite a list of celebs who stayed at Magnolia to sustain the Juke Joint Series for quite a while. Duke Ellington almost made the list. “Duke didn’t stay here, but his band did, “ Pass says. “Duke was comfortable enough financially to have his own rail car. So he stayed in his own car on that train,” he explains. “Ray Charles stayed here, Ike and Tina Turner, James Brown, heavyweight champ Ezzard Charles. Jackie Robinson, Satchel Paige, they came here to play at War Memorial Stadium. And Ruth Brown stayed here; she was very hot, had top billing on the Chitlin’ Circuit. Gladys Knight and the Pips, stayed here, Smokey Robinson stayed here, The Midnighters stayed here. Buddy Gist donated Miles Davis’ trumpet to UNCG. He talked often about how his mother used to cook for Louis Armstrong when Armstrong would come here. The place was just the vortex of the African -American community here,” Pass says.

Pass and family hope to return to the Magnolia House’s long tradition of hospitality both for events and as a bed and breakfast. “We hope to cater to the furniture market when we finish upstairs,” Pass says, referring to the five bedrooms on the top floor, two of which are fully completed and ready for guests, but currently used only for family and friends. “People who own homes in the High Point area rent out their entire houses to people who come to furniture market. We’d be interested in doing that same thing with the Magnolia House,” he says explaining that they would offer a full package of services — concierge, transportation to Market, for example.

To kick off Black History Month, Miller has organized an event to share the Magnolia House’s current path and history with the public. “We’re calling it our Magnolia Table Talk. And it’s the Green Book edition because we’re celebrating that we’ve been listed in the Green Book for six of their editions,” she says. Miller adds that she envisioned the event as an upscale intimate setting “with my dad and all of his siblings sitting at the table leading a panel discussion with the audience, talking about the history of the Magnolia House, how it tied into history of the Triad and how our family line contributed to that history of the Triad as well.” Pass says that the Magnolia House resurrection is for his community as well as his family: “I restored it because I am interested in preserving our history. My grandchildren won’t know where they’re going until they know where they’ve been.” OH

Grant Britt lives in a much humbler abode than the Magnolia House, but he shares the same reverence for its soulful musical guests who provided the soundtrack of his young life and still resonate in his residence and his head.

For a complete list of events open to the public at The Historic Magnolia House, please visit thehistoricmagnoliahouse.com.