Fantasy houses near and far

By Cynthia Adams

Illustration by Harry Blair

When I asked a wise and close friend who had just bought a townhouse whether she’s found her dream house, she replied: “Ha ha. My dream home fantasy comes with a secretary, or is self-vacuuming.”

My own fantasy property is old enough to have weathered several epidemics, including the cholera outbreak in the 1830s. Its location is somewhere warm, where languid breezes lift the curtains at the French-style windows that open from the floor to nearly the top of the 16-foot ceilings. I picture it in the Garden District of New Orleans, home to some of the best Southern writers who have ever drawn breath. (With enough ruin, moral decay, absinthe and jazz to inspire volumes.)

Limestone bearing the dint of age would extend from the foyer throughout the first floor, a light-flooded expanse thanks to an oculus at the top floor. The generous staircase would also feature limestone; worn by the generations of feet who have traveled it.

This dreamscape has grounds to roam, reflect.

Even a house landlocked on a city square like the Harper Fowlkes House in Savannah would do — the gardens are dense with plantings, and its stature elevates it above the fray. Sweet Savannah, with the largest historic district in the United States and Lowcountry cooking — and more than its share of turpitude, as revealed by John Berendt’s Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil.)

House-lover Jackie O. visited nearby Mercer House when Jim Williams, the central figure in Berendt’s book, lived there. Williams was a huge preservationist and died in his downstairs library. Ironically, no Mercer ever lived there, but Williams saved it from ruin.

In the blue hour of a Savannah evening, high above the Bonaventure cemetery, a dove cries as I pour myself another.

As with any great fantasy, the grounds and setting are vital, recalling Jefferson’s Monticello or Vanderbilt’s Biltmore. Much of the dream builds on itself: tightly clipped boxwood hedges are involved; also, a pea gravel front courtyard. And burbling fountains, olive trees in ancient pots, and Floribunda roses.

A reflecting pool lies at the end of a wending, mossy rill. The rill leads the eye from the stone terrace, which is beyond a generous pergola.

Preferably, all flowers are white, much like the ones writer Vita Sackville-West preferred. Moonflowers open in the twilight.

But meantime, my reality is not that vision no matter how much I squint my eyes.

Dream projects never completed and dream houses haunt us. My father’s dream house, his home place, burned down before its restoration was finished.

Even for some who’ve built their fantasy home, the dream lives in perpetuity. Take retired anthropologist Tom Fitzgerald, who built an architect-designed house with an inner courtyard in Sunset Hills.

“This home about captures the fantasy,” he says. But he’s not hesitant to add a dream setting: “I would also have liked to be in a warmer climate and have a house facing the sea or a body of water, but like this house — open, airy, tall ceilings, small yard to look after.”

Like Fitzgerald, Sharon James, who lives in Stoney Creek, is a house-lover and collector. James built a dream home when she lived in Chargin Falls, Ohio.

From her home and garden in Whitsett, she’s quick to describe her imaginary abode in minute detail:

“A beautiful early 19th-century Greek Revival, all white with columns and furnished perfectly of the period! Fourteen-foot high ceilings, heart-pine floors, beautiful windows that raise from the bottom. Wonderful crown moldings and door surrounds and gorgeous staircase to second and third floors,” James writes.

As for the grounds? “Surrounded by beautiful lawns and French parterre. Large veranda front and back. How is that for starters?”

Those of us who literally dream of houses, and by the way, I am one, thank you very much Sigmund Freud, hunger to glimpse how the other half lives.

News junkies took advantage of a virtual oculus (Latin for “eye”) opened by Covid-dictated broadcasting from celebrities’ homes.

Twitter’s Room Rater, developed by a bored Washingtonian who felt we needed a little laughter during quarantine, had over 200,000 followers at last count. Feeding a public obsession with fame — not to mention the human tendency toward voyeurism — the site ruthlessly rates celebrity spaces. Art, bookcases, light placement, even wall color determine a score on a scale of one to 10. As the site’s viewership soared, celebs began to take notice and took measures — often in vain — to up their scores.

Not unlike the novice Zoomer who inadvertently revealed her most private of privates when she carried her laptop along to the powder room, many A-listers demonstrated they were not quite ready for prime time.

We Zoomers-and-doomer preppers, cats and kittens living in TV Land, discovered even our idols who hold a lofty position on a pedestal may or may not inhabit a dream house.

News celebs had to strike a balance in their choices of settings: professional without being too aloof. Attractive without looking too personal. Or just less messy and distracting.

Anderson Cooper fueled viewers’ home fantasies when he briefly broadcasted from what looked like his den/study. Design bloggers were in seventh heaven, commenting on the malachite wallpaper (or was it faux painting?) and the gold bound tomes on his bookshelves. CBS anchor Gayle King moved around her Manhattan apartment, plunking down at her ritzy dining room table, using real wallpaper — not virtual! — as her backdrop. The dining room’s beautiful yellow paper (Harlem Toile de Jouy) blew up the blogosphere. Sheila Bridges, the wallpaper designer, was thrilled when excited clients phoned, identifying the pattern. It continued to make ongoing guest appearances as King cycled through settings.

Other broadcasters, like CNN’s Chris Cuomo, reported from the all-white and neutral basement of his Long Island home while in a fever dream state induced by COVID-19. The space was spotless — but more lab than fab. It lent a devastating veritas as Cuomo’s illness progressed. But it might as well have been a set from a sci-fi flick. We learned from these makeshift home setups how these people actually live. Without stylists, lighting experts and makeup artists, they’re just schmoes in their basements! And like Cuomo’s, uninspired basements at that.

Talk about unfulfilled home fantasies!

Over years, I’ve kept a file of clippings of houses I considered ideal. To review it is to travel back to a time when I thought living in a great English pile and swanning around in a Laura Ashley number was the peak of chic. (I still own a pink Laura Ashley jumpsuit, by the way.)

Time was, when I would have given a kidney to meet Mario Buatta, the Prince of Chintz. Fans of Bravo’s Southern Charm and Charleston, South Carolina, maven Patricia Altschul know she was a devoted Buatta client.

He died in 2018. But chintz, dear readers, lives on.

Dreams, when realized, not so much. When I was younger, and going through a primitive furniture phase, I dreamed of owning a true saltbox — having taken too many trips to New England, Williamsburg and Old Salem.

Tragically, I got my wish, building a version of a saltbox in a brand-new development.

The outcome was rusticated, homespun madness, with interiors so dark they probably contributed to my need for counseling. The house sat on a cul-de-sac nicknamed Knot’s Landing after the 1980s melodrama, as one by one couples divorced and decamped.

My rustic dream home on Knot’s Landing wore rough-hewn barn siding with actual knots in the “great room” and wide pine floors throughout the downstairs. The end effect was more of a Great Gloom.

Coveting the dinged or dull pewter pieces of yesteryear I decorated with salt glaze pottery, rag rugs and quilts — except for the crazy quilts I inherited, which were too colorful. Distressed furniture, either real or reproduced, was my jam. It was a time when people actually beat floors and furniture with chains in order to achieve a weathered appearance.

I owed much to Ethan Allen for inspiration and Country Living magazine whose interiors I memorized. New England’s Country Curtains provided the tab style curtains that I hung onto wooden rods, successfully blotting out the little light from the house’s very narrow windows.

The result was unique in a way that had made my younger self proud. In retrospect, my tastes evoked Ethan Frome more than Ethan Allen.

Sedgefield Realtor Pickett Stafford called me to candidly discuss the light-starved house after a showing when my marriage collapsed. “Were you depressed there?” she asked diplomatically, knowing it was a rhetorical question.

Once the faux saltbox was sold, I escaped cul-de-sac purgatory, got contact lenses and realized I hadn’t been able to see very well for about five years.

Designer Todd Nabors’ fantasies focus on a weekend/vacation retreat: “A vintage mountain cottage covered in chestnut bark at Linville.” Although the coast would also do as Nabors’ dream setting, specifically “one of the original shingled houses from the 1920s near the Carolina Yacht Club on Wrightsville Beach. I have the decoration for each all worked out in my mind’s eye!” And the designer also entertains fantasies about European villas.

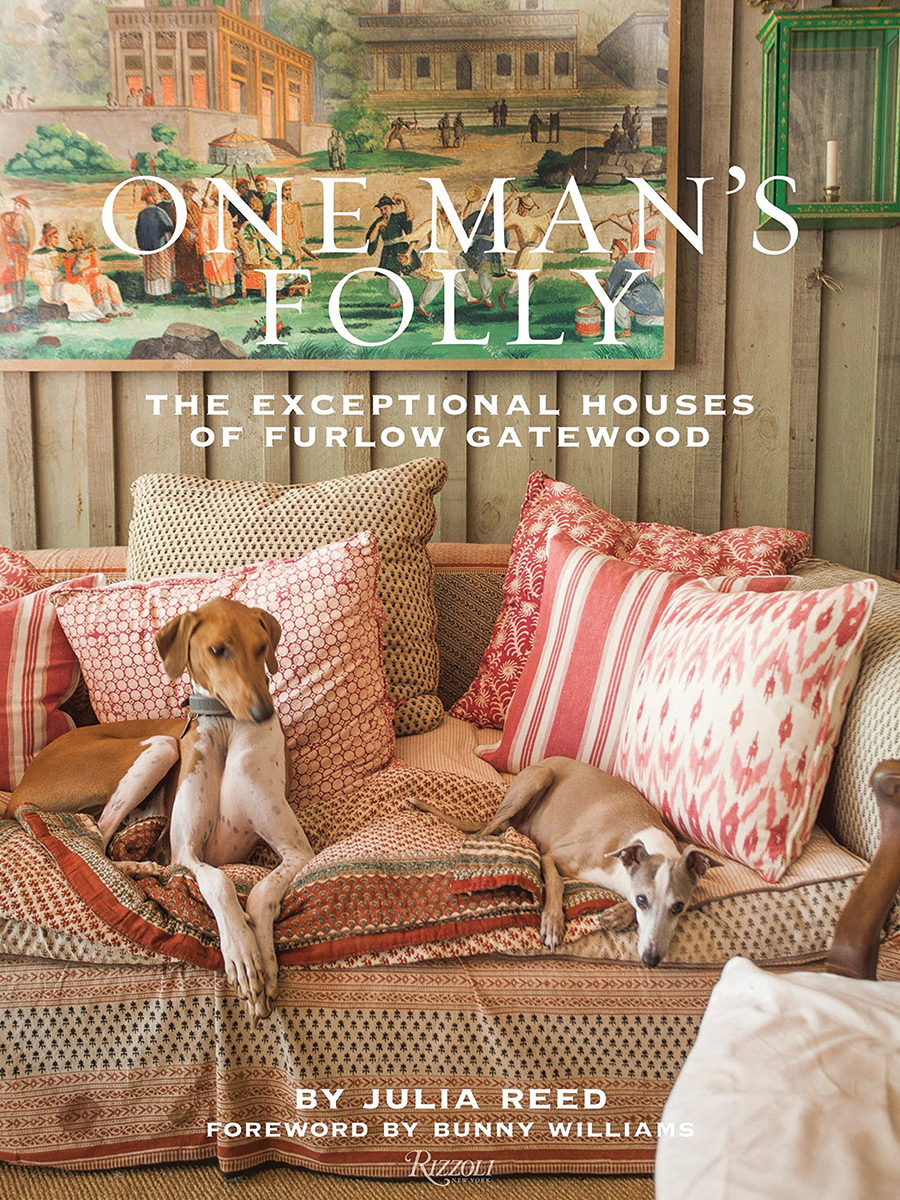

Then there is the ultimate fantasist: Furlow Gatewood, who lives the dream on a small compound. You may be in the Furlow fan club if you too own a copy of One Man’s Folly: The Exceptional Houses of Furlow Gatewood, the book that fueled my own fandom.

Gatewood is known mostly among preservationists like Pratt Cassity, who visited the designer in his home base of Americus, Georgia and praised Gatewood’s genius for a sense of place. “The middle Georgia landscape is one that is rewritten by the order of row crops, orchards, and engineered grids of small towns. Settled quietly in one of these ordered yet oddly natural landscapes is a collection of handsome architecture,” Cassity writes from splendid isolation in his own historic home in Athens, Georgia.

“The Gatewood residences,” he continues, “are each perfectly balanced but work as a whole much better. They support the total design of this little bit of evolved landscape. The interior design is the creamy and sweet surprise inside. Everywhere you look you see very familiar objects, art, views, plants and buildings but somehow you’ve never seen them this way before.”

For Gatewood has moved not one, not two, but four formerly ruined homes to his 14-acre property and restored them. To perfection. I first read about them 13 years ago in a piece by Julia Reed for Veranda magazine and was instantly mesmerized. Because Gatewood is quite literally living out his dream. He has my heart.

He resides in “the Barn,” which is anything but, and once a carriage house. The “Peacock House” featuring bewitching French doors and columns were chief among the reasons he simply had to have it.

The “Cuthbert House” was trucked 65 miles to Gatewood’s compound in order to rescue the beauty from a wrecking ball. This mid–19th-century Gothic house had to be sawed in half in order to transport it.

Where others saw a ruin worth trashing, Gatewood saw the faux stone exterior and beauty in its vernacular design, the 16-foot ceilings and moldings.

He sponsored trucking the “Lumpkin House” a mere 40 miles to save it, as well. Again, Gatewood explains it had doors he could not resist. Also irresistible to him were the original transom windows.

One should approach Gatewood’s compound driving a British Racing Green MG with the top down, a gentle summer breeze stirring, to best appreciate the potted blue hydrangeas lining the drive, their mop heads bowing in gentle greeting.

Peacocks stroll through the property, the namesakes of said Peacock House.

But even for someone like Gatewood, reality intrudes on the platonic ideal of home. Where he falls down: the kitchen.

The one kitchen photographed for the book is nondescript. An afterthought. Ditto for baths.

Having cooked considerably more in the past few months, I renew my wish for a proper AGA stove. Also, limestone flooring in the kitchen, which would not have fixed cabinetry but be outfitted like a room in the manner of the best European kitchens. A wonderful French table, bearing the scars of years of use would stand in for an island. Limed walls, perfectly aged would show patina, as would an enormous fireplace. Casement windows and French doors open to the rear garden. An antique greenhouse, painted deep green, does double-duty as entertaining space.

Despite an initial cleaning, fluffing, and rearranging spate, during the shelter-at-home mandate, there were days when I strongly considered some kindling and a match. The downstairs bath’s ceiling plaster has begun a curious blooming; the gray tile walls need to go. My laboriously painted stripes above said tile now bore me stupid.

Demolition is my current obsession. The thing most needing demolishing taunts me: our termite-riddled 94-year-old garage.

Just imagine it transformed into a gabled board and batten carriage house featuring a Dutch door and ribbed metal roof! Envision the interior with a mini kitchen and sitting room, brick flooring, and beadboard paneled walls! White-washed beams and salvaged architectural flourishes. An outdoor shower would allow for splashing off after tending an idyllic white cottage garden.

There would be an outdoor fireplace and wisteria-heavy pergola for entertaining.

Wait — make that exterior stone, with a moss garden, and a low wall perhaps?

Can’t you just see it? OH

Contributing Editor Cynthia Adams admires house-mad Edith Wharton, who wrote to “decorate one’s inner house so richly that one is content there, glad to welcome anyone who wants to come and stay, but happy all the same when one is inevitably alone.”