Wandering Billy

12 Cent Dreams

Remembering a local legend in ink

By Billy Ingram

“Comic books helped me to define myself and my world in a way that made both far less frightening. I honestly cannot imagine how I would have navigated my way through childhood without them.” — Bradford W. Wright

Wright’s not wrong. As a young comic book collector, one of my fave artists was Murphy Anderson. His fluid brushwork bestowed an air of sophistication few artists of that genre possessed. I was surprised to learn, years later, that Anderson was born and raised in Greensboro before moving to New York to work for DC Comics.

Wright’s not wrong. As a young comic book collector, one of my fave artists was Murphy Anderson. His fluid brushwork bestowed an air of sophistication few artists of that genre possessed. I was surprised to learn, years later, that Anderson was born and raised in Greensboro before moving to New York to work for DC Comics.

Murphy C. Anderson Jr. recognized early on the transformative power that words commingling with pictures could have on the imagination. As a youngster in the 1930s, he’d spend hours lying on the living room floor of his North Spring Street home poring over the comic pages of local papers and, on Sundays, the New York Journal-American, which allowed him to follow the adventures of The Phantom, Mandrake the Magician, and his favorite strip, the scientifically forward-looking Buck Rogers in the 25th Century.

Amy Hitchcock, a former classmate, says, “At Central Junior High there were two boys that sat together all the time and they drew in their notebooks all the time. My impression of Murphy was that he was withdrawn, quiet and always did his own thing, but he was pleasant.” Later, Anderson and Greensboro newspaper legend Irwin Smallwood would become co-editors of Greensboro Senior (now Grimsley) High School’s newspaper.

A college dropout facing certain military service in 1944, Anderson borrowed $100 from his skeptical father to make the rounds of New York City’s funny book publishers. Unknowingly, he was marching into what has become known as the Golden Age of Comics, so christened because sales were so astronomical, upwards of 6 million copies per title.

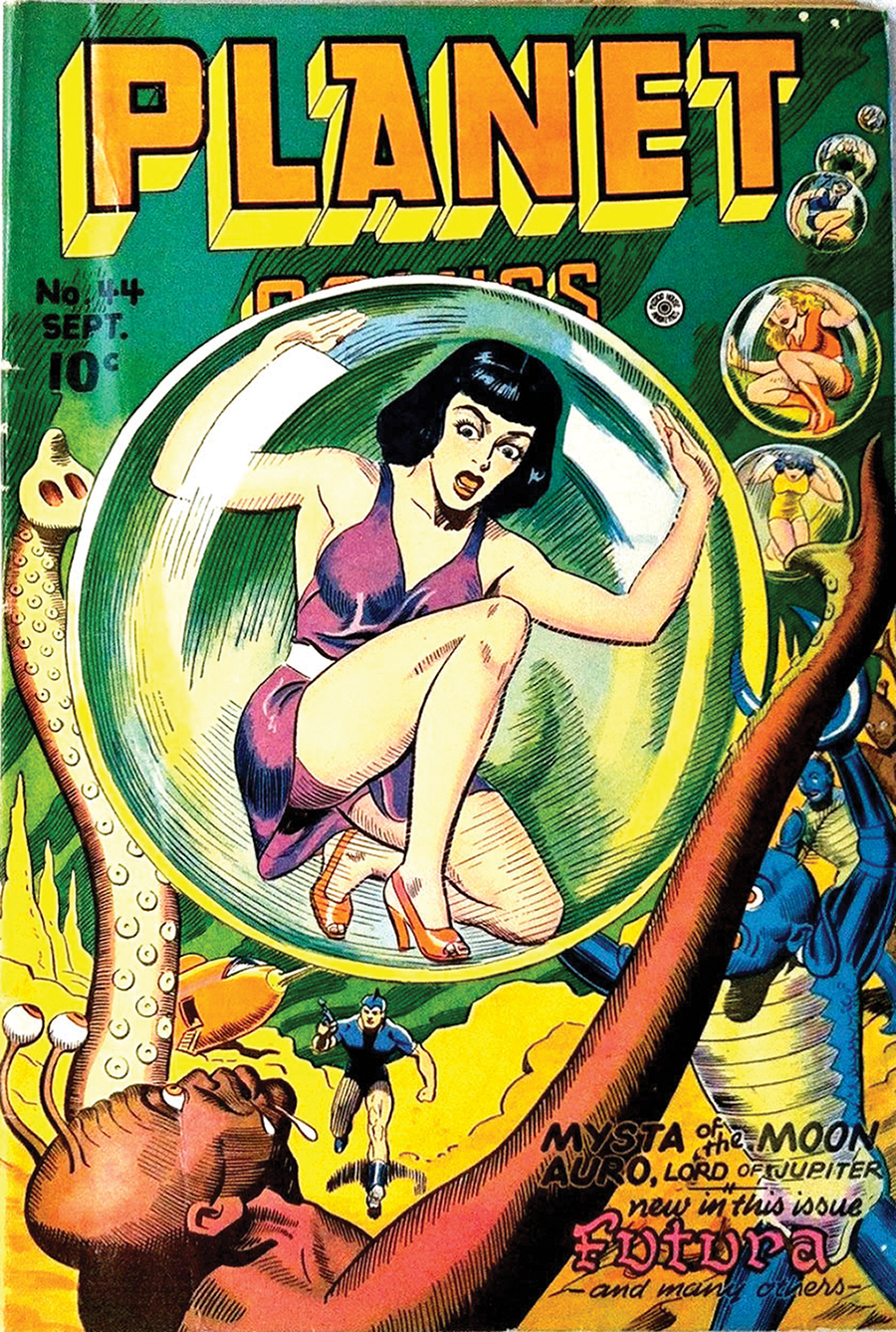

Anderson landed a gig illustrating for Planet Comics, whose main selling point seemed to be the undulating breasts belonging to whichever curvaceous blond was being snatched up by salivating bug-eyed monsters that month. He continued slinging ink for Fiction House while serving two years in the Navy, stationed in Chicago, where he met his soon-to-be wife, Helen. Completing his military stint in 1946, he happened upon a notice from the National Newspaper Service in search of an artist for Buck Rogers in the 25th Century. Anderson took over daily art chores in 1947. “I grew up on Buck, it was a dream come true,” he related decades later.

Anderson left Buck Rogers in 1949 just as the golden age of comics was drawing to a close. He and his bride made their way to Greensboro, where, during the day, he served as office manager for his father’s fledgling business, the Blue Bird Cab Company.

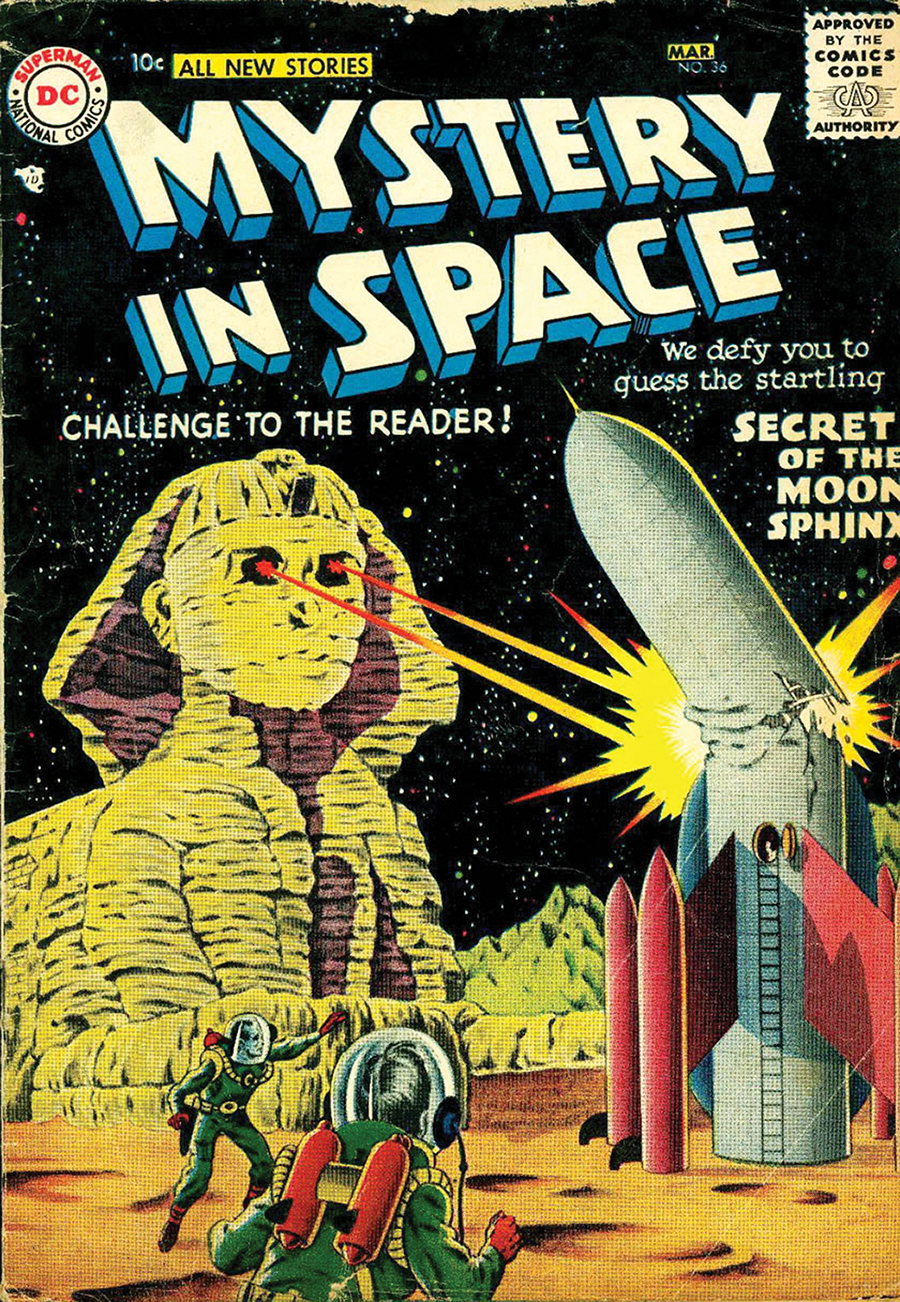

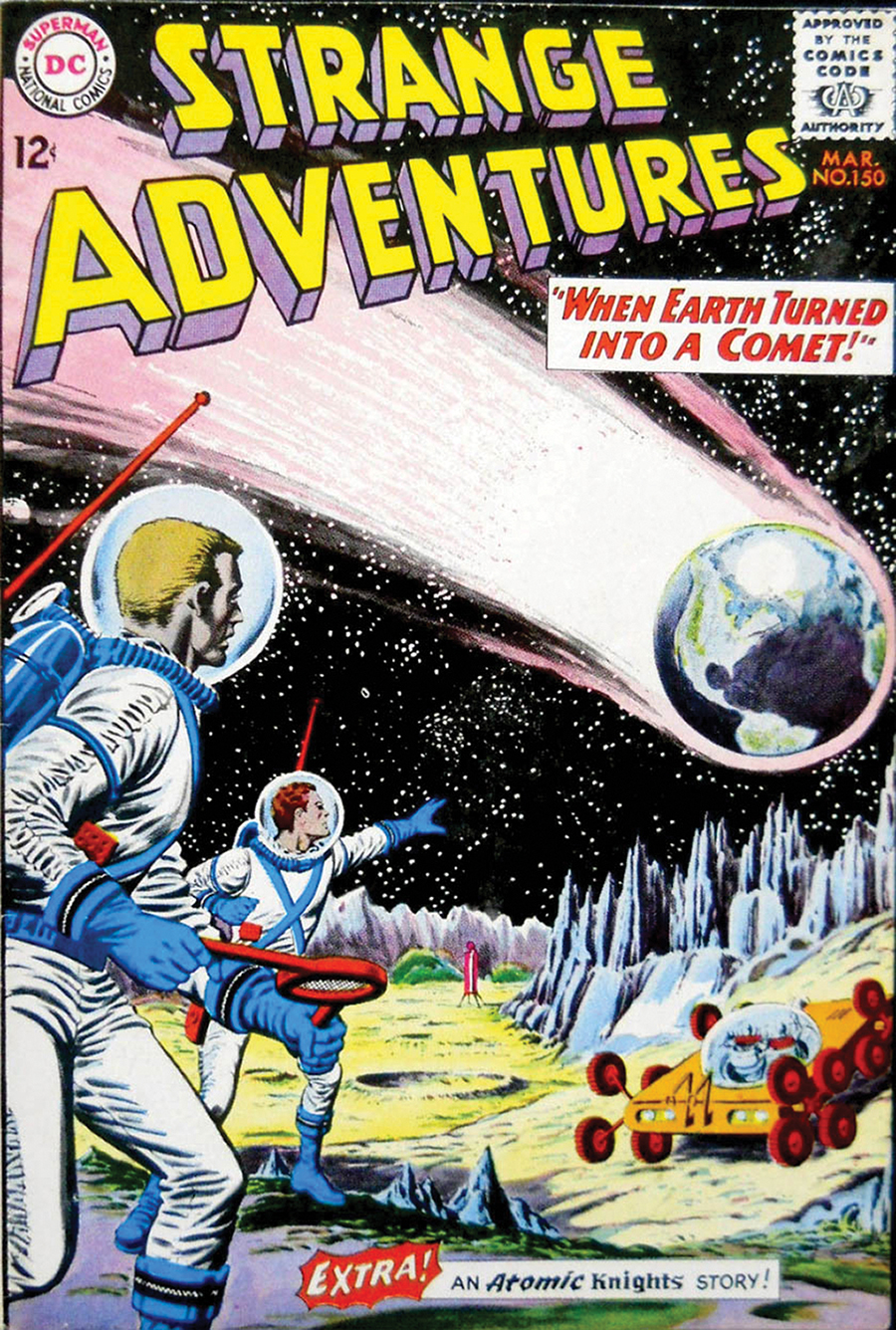

Before long, Anderson was once again canvassing the concrete jungle. Julius Schwartz, editor for National Periodical Publications’ (as DC Comics was known in 1951) new line of science fiction comics, recognized Anderson’s work as compositionally superior to and more finely rendered than many of the company’s slickest artists. Schwartz met with him and sent him home with a script to illustrate.

Schwartz allowed Anderson, now with children and not ready to give up his Carolina roots, to mail his contributions in from Greensboro, an unheard of arrangement. Still trafficking for Blue Bird Cab, Anderson spent his nights conjuring up compelling covers populated with pointy-eared giants capturing fighter jets in butterfly nets, radioscopic weirdos from other dimensions invading and terrifying the tourists, and genetically superior gorillas confounding the laws of man and nature. Stories were then written around his phantasmagorical scenarios.

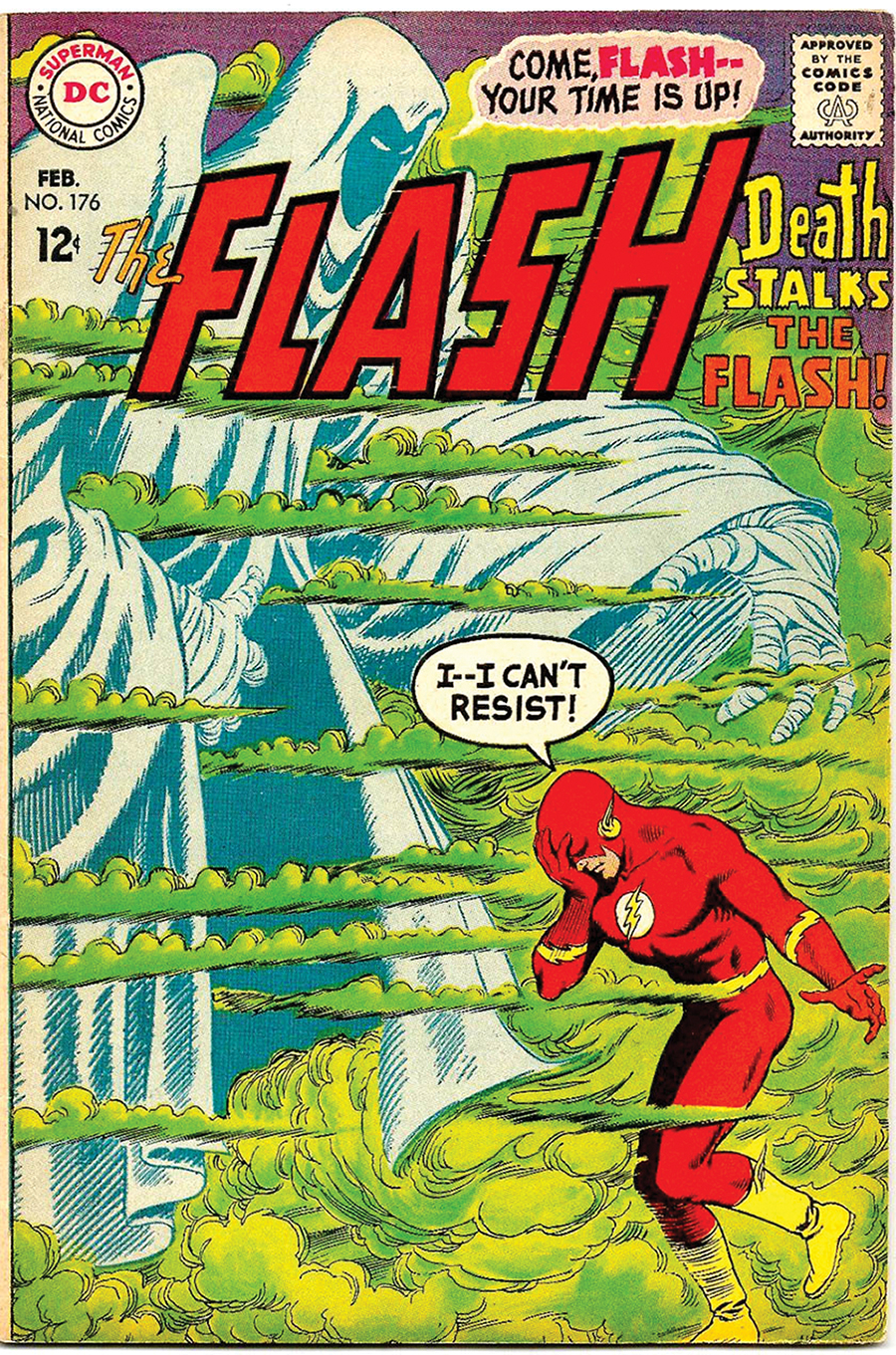

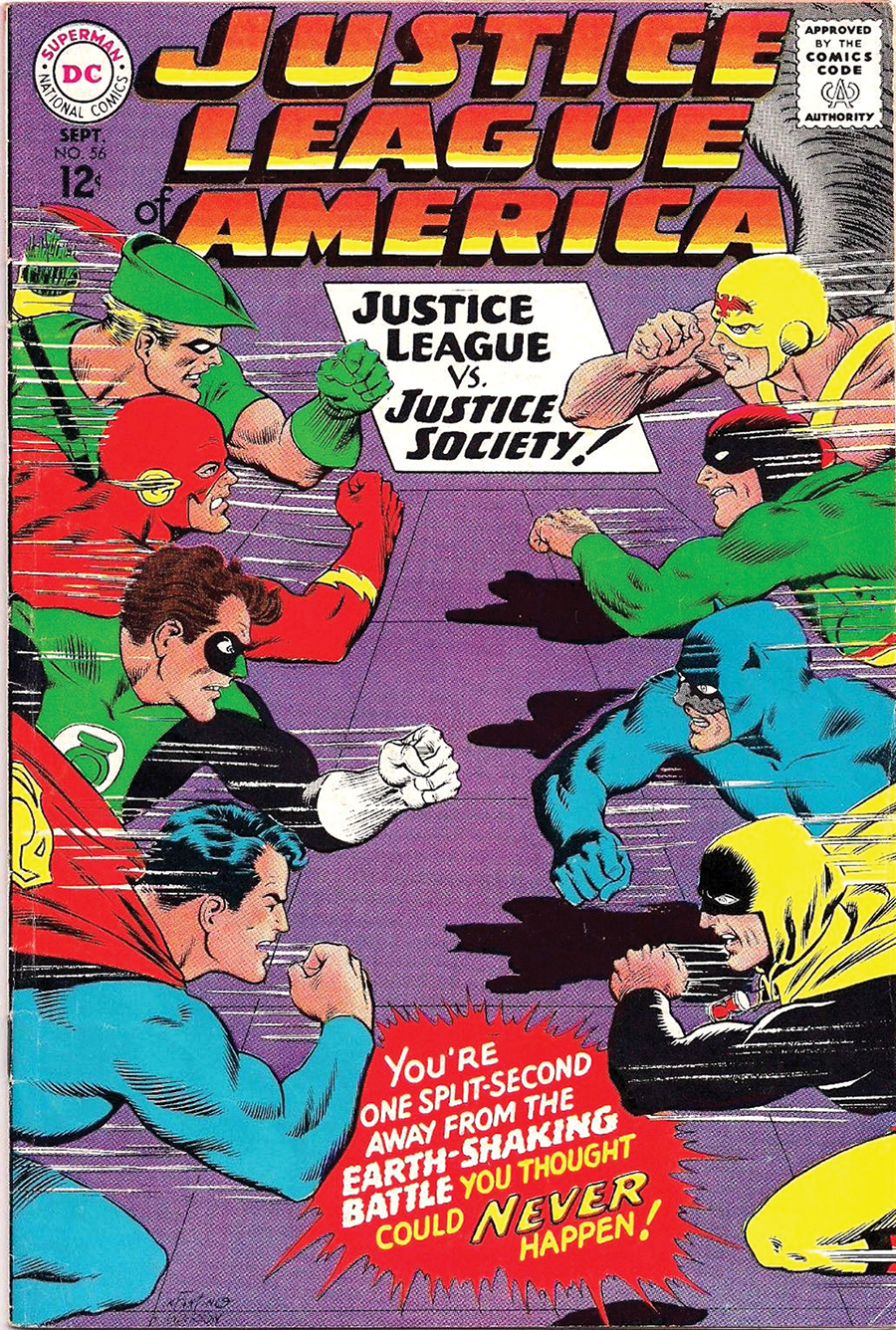

The family relocated to New York in 1960 in order for Anderson to work full-time for DC, a company undergoing an unexpected resurgence. On a whim four years earlier, editor Julius Schwartz had re-imagined one of the brand’s dead-as-a-doornail superheroes from the 1940s, The Flash. With this act, the Silver Age of Comics was born. Anderson’s meticulous flourishes defined DC Comics’ house style of the ’60s and early ’70s — so much that Schwartz preferred to have him inking others’ pencilled art, most notably Carmine Infantino (Adam Strange, Batman) and Gil Kane (The Atom, Green Lantern).

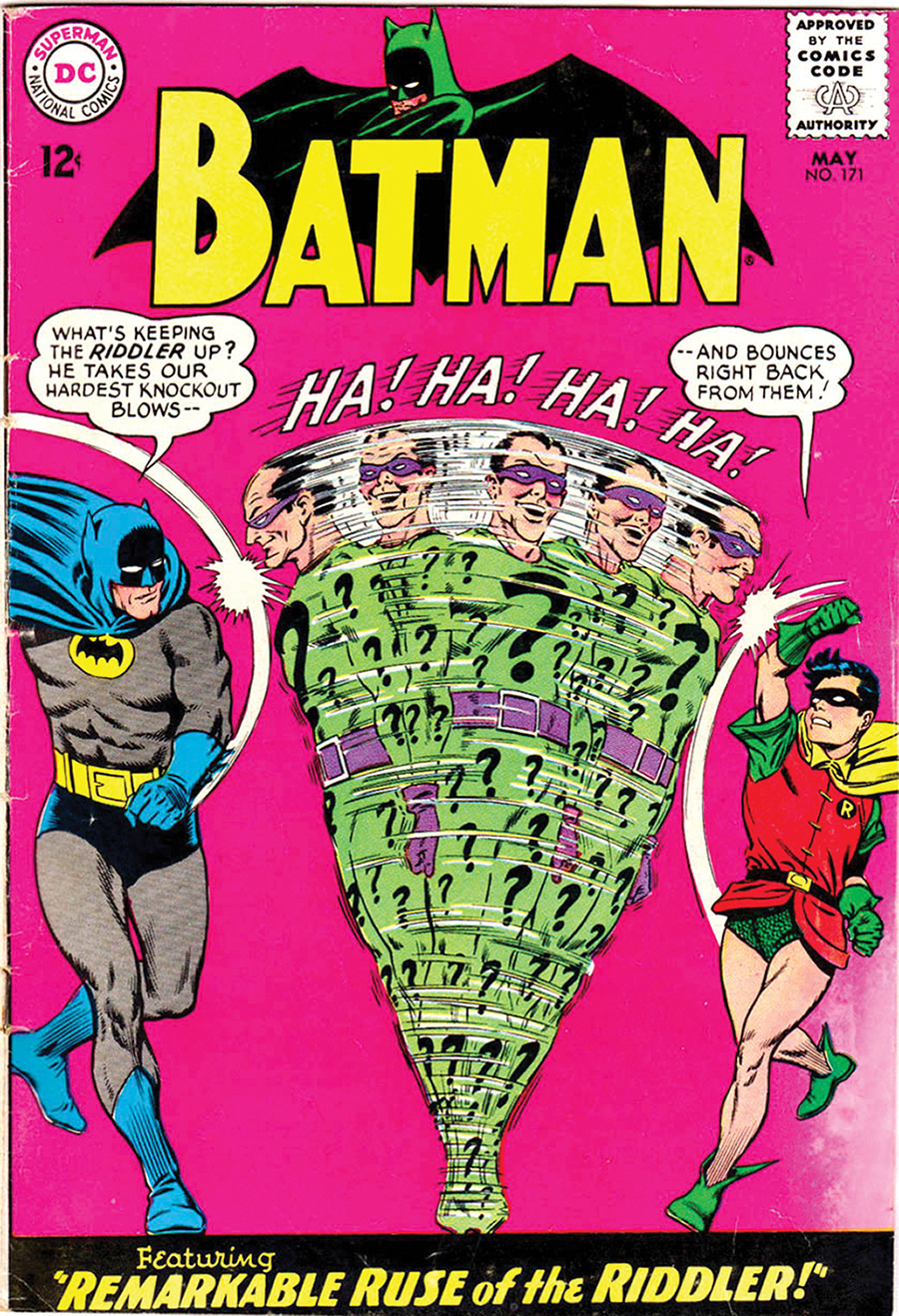

Meanwhile, years of poorly drawn short stories with Batman, Robin, Batwoman and Ace the Bathound confronting bulbous-bodied aliens and overcoming silly transformations (“Batman Becomes Batbaby!”) led to sales so dismal that cancellation of the entire Batman line was all but certain. Schwartz was yanked off the sci-fi comics in 1964 and given six months to save the bat-franchise. The result was a monthly onslaught of playfully gripping covers sketched by Infantino, the best of which were inked by Anderson, re-introducing The Joker, Riddler, Catwoman and Batgirl to a new generation. By 1966, business was booming when the Batman TV show sent DC’s sales into hyperdrive.

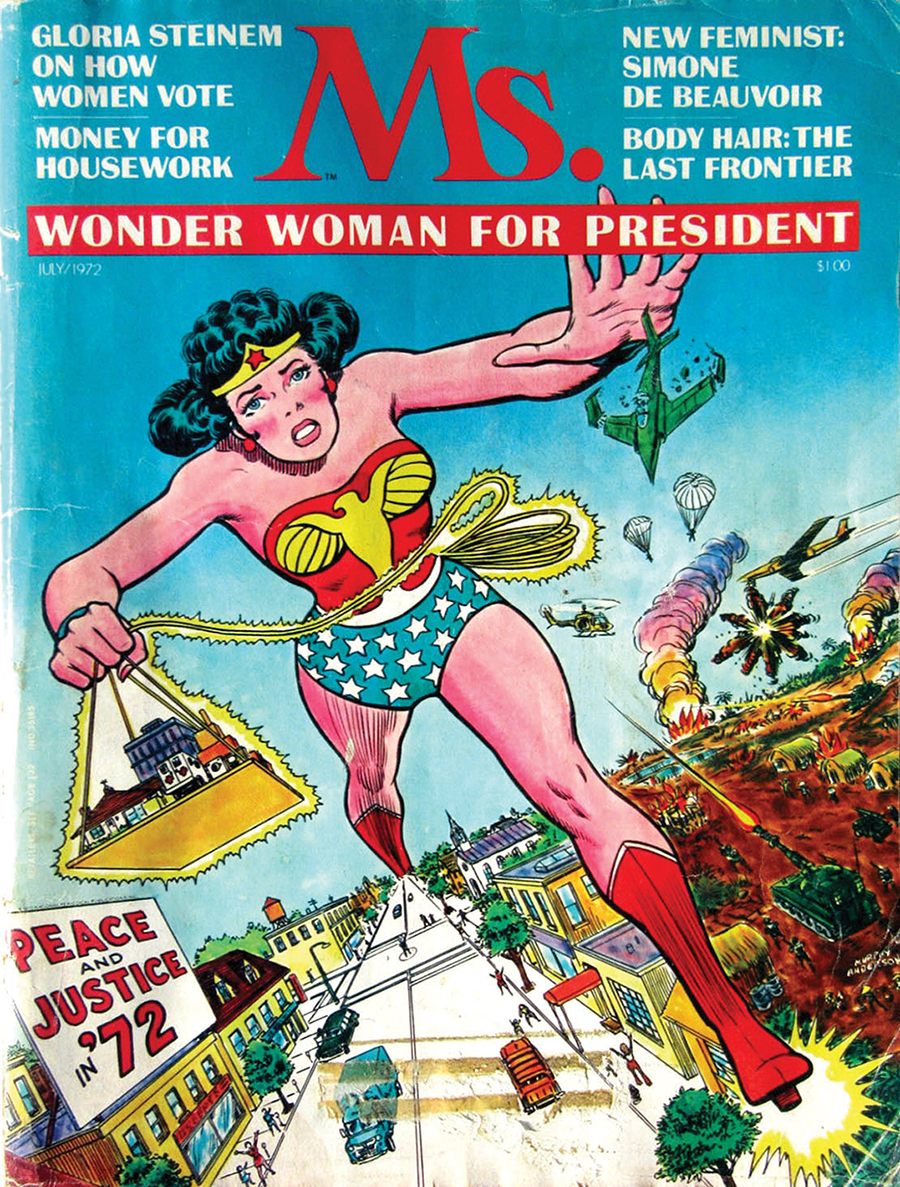

When Schwartz rebooted Superman in 1970, Anderson was teamed with Curt Swan. So meshed were their styles that the duo took to crediting their art as “Swanderson.” Then, in 1972, the Greensboro native’s dynamic portrayal of Wonder Woman graced the first issue of Ms., becoming one of the most striking and culturally significant magazine covers of that decade.

In a twist not unlike those found in the comics, it was Anderson’s one time schoolmate Amy Hitchcock’s son, John, who organized Greensboro’s first major comic convention in 1983, featuring Murphy Anderson as a guest of honor. “Murphy was here in 1985 when Jack Kirby was here,” John Hitchcock (owner of Parts Unknown: The Comic Book Store) says, a significant moment since the only controversy in Anderson’s career came when he was asked to redraw Kirby’s Superman faces to more closely conform to the DC style. “[Anderson and Kirby] were in the kitchen of my apartment when Murphy went up and apologized to Jack. He was always embarrassed that he had to change his artwork because he had so much respect for Kirby. Jack went out of his way to thank him and say, ‘Murphy, that’s OK. That’s the way business was back then. I have no ill will,’ and they shook hands. That shows you what a great guy Murphy was — it bothered him all those years.”

Murphy C. Anderson Jr., universally respected as both draftsman and gentleman, passed away in 2015 at the age of 89. He left behind his wife of 67 years, Helen, two daughters, a son, grandkids and an indelible impression on millions of thrill-seeking comic book lovers everywhere. OH

Billy Ingram still has comic books he purchased from a spinner rack located next to the back entrance of Woolworth’s downtown.