From a dozen hidden springs comes fabled Buffalo Creek, a once-troubled waterway along which generations of Greensboro folks have played ball, pitched woo, made their morning run or evening walk. A meandering story of love and rebirth

By Grant Britt • Photograph by Mark Wagoner • Illustrations by Robin Sutton Anders

For those lucky enough to live in its proximity, it’s a pathway to pleasure, a ribbon of water that positively impacts their daily lives. Meandering through town at a leisurely pace, Greensboro’s Buffalo Creek supports a raft of stuff that’s good for what ails you. It’s a wildlife habitat, a stress-relieving space that can be stared at or galloped alongside on foot or bicycle, and a wild if short- lived thrill-seeker’s passageway if approached and mounted after a downpour. Like many waterways in urban environments, the mighty Buffalo has had its share of woes, including circulation problems restricting its mobility, breathing difficulties, and general health and well-being, as well as having harmful stuff dumped down its throat by man and nature.

“I remember when we first bought this house here, I could get a running start and jump across Buffalo Creek,” says retired EMT Larry York, who has lived in the Westerwood subdivision on Hillcrest Drive since the late 1960s. “At that time they had cleared everything out; there was no vegetation growing there, and the erosion that was occurring was just off the tracks.”

York and buddy Ben Matkins went to the city and suggested that they stop dredging the creek and let the trees grow up around it to act as a buffer. “The city thought we were crazy,” York says. “The city engineer said, ‘Well, we need to get the water out of here as fast as we can.’”

York says the two of them tried to reason with the engineer: “‘Look, you have partial dams on the creek when it gets flooded. They’re called bridges. And there’s only so much water that’s going to go underneath those bridges.’ It made you understand that engineers didn’t understand the theory of water rolling downhill and gravity sucking. We played on that creek for years.”

It wasn’t all play, however. Ben Matkins, who passed away in ’96, was an avid environmentalist, a Sierra Club member and former president of the Audubon Society. He was also a political gadfly.

Matkins and York started their political careers together, fueled by civic fervor, a few beers and a love of Buffalo Creek. “We both ran for city council back in 1980,” York says. “We were sitting up in Ham’s one night; we were drinking, talking about how screwed up the city was. And I said, ‘Ben why don’t you run? I’ll support you any way I can. At least you’ll get one or two votes.’ And he said, ‘I’ll tell you what. I’ll run if you will. We’re gonna turn so many heads they’re gonna wonder what’s happened to ’em.’ And it did.”

Both candidates lost, but they did get some attention, and their continued, concerted efforts, with the help of other close friends and neighbors and the Audubon Society, gradually brought about important changes for Buffalo Creek.

The Source

When you look at a topographical map of North Carolina, there are a plethora of squiggly lines spread across the state like varicose veins, quite a few with some version of Buffalo in their names. But while Greensboro’s Buff does originate in the state, it doesn’t trickle off any other tributary or wean itself from any mightier flow by nefarious meanderings.

“Buffalo Creek and all its little tributaries start up along Spring Garden Street,” says former UNCG chemistry professor Jack Jezorek, current co-chair of the T. Gilbert Pearson Chapter of the Audubon Society. “The name Spring Garden Street says it all. The railroad runs along what’s now Gate City Boulevard on one side, Spring Garden Street on the other side.” The railroad, he explains, runs along a ridgeline. “The railroad always is built on the highest ground. Lot of roads are that way too. There are lots of little springs and seepages along the north side of the railroad along Spring Garden Street.” Jezorek goes on to say that when UNCG’s Weatherspoon Art Museum was built 25 years ago, problems developed, “because they dug down, and lo and behold, there were a whole bunch of springs on Spring Garden Street.” He laughs. “So all these little tributaries you see around town, they all start right around Spring Garden Street.”

That takes care of the birthing of the North Buffalo. The South Buff is born from more seepage, down south a ways. “You know the term Sandy Ridge Road? That’s another ridgeline,” Jezorek says. “If you go west of Sandy Ridge Road, you’re now in the Deep River drainage — Deep River, Oak Hollow Lake, down to High Point. On the east side, you’re in the Buffalo Creek drainage. So there’s North Buffalo Creek, which runs through Westerwood here at Lake Daniel Park, and South Buffalo, and they join out near McLeansville to become just Buffalo Creek.” Farther downstream, he says, they join up with Reedy Fork Creek. “And it’s Reedy Creek which joins the Haw over towards Burlington.”

Matkins didn’t get to see his vision of the Buffalo realized, but his efforts encouraged others, and finally the city took notice.

The natural buffers that he and York and Jezorek and County Commissioner Joe Wood and Westerwood neighbors advocated came to fruition in the early ’90s’ with the help of former Mayor Carolyn Allen with a project she dubbed StreamGreen. “We took a Greensboro city map, glued it to some poster board, and we drew with a blue magic marker all of these little creeks that you see all over town,” Jezorek says. “We’re right at the headwaters of this Buffalo creek system, and it is amazing. Every little dip in the road on Friendly, on Market, any other street in town, every time the road dips down, you can bet there’s a creek down there. A lot ’em are piped when they were small, a spiderweb of creeks.”

Almost every little hillside in town has a little seep, and down at the bottom of the hill there’s a little creek, a little drainage. “They’re all over town, which is nice because it means it’s pretty clean water,” Jezorek says. “We’re fortunate we’re at the very headwaters of the Cape Fear. Cape Fear is formed from the Haw and the Deep. When they join below Jordan Lake dam, that’s where the Cape Fear starts. So we’re in the Cape Fear drainage, and we’re lucky because our water’s pretty clean up here, nobody else uses it but us.” With that comes an obligation, he says, “to take care of that water so that the folks downstream don’t have crappy water, and that was one of the points of the StreamGreen project, to take care of these creeks, keep their banks from collapsing with vegetation, roots holding banks in place.”

Mythical Beasts

It might make a good argument to claim the mighty Buffalo was named for a shaggy creature who might have denuded those banks in a quest for a grazing paradise. Nice try, county historian James G. W. MacLamroc informed Greensborians in a ’72 News & Record Hot Line response asking about the creek’s namesake. His research indicated that Buffalo were rare around these parts when early settlers moved here in the mid-1700s, so it’s unlikely the beasts donated their name to the stream. More likely, whoever laid the name on the waterway just chose it because the mighty bison projects a strong American image for a creek, a robe or a nickel.

In his 1709 travelogue, surveyor John Lawson presents an in-depth scrutiny of North Carolina’s climate, waterways, wildlife and botany, with help from his Indian guides. Despite his jaw-breaking title, A New Voyage to Carolina; Containing the Exact Description and Natural History of That Country: Together with the Present State Thereof. And a Journal of a Thousand Miles, Travel’d Thro’ Several Nations of Indians. Giving a Particular Account of Their Customs, Manners, & c., Lawson’s account is fun to read. In those days, beasts were apparently quite abundant, and a partial listing of Carolina’s wild denizens included the “Buffelo,” or “wild Beef,” as well as “Cat-a Mount, Tyger, Polcat, Bever and Bearmouse.” Despite his inclusion of the shaggy behemoths in his Carolina zoology, a bit later in his accounts he admits that the “buffelo” seldom roam the Carolinas, preferring for some reason the wilds of “Messiasippi.” “The Buffelo is a wild Beast of America, which has a Bunch on his Back, as the Cattle of St. Laurence are said to have,” Lawson wrote. “He seldom appears amongst the English Inhabitants, his chief Haunt being in the Land of Messiasippi, which is, for the most part, a plain Country; yet I have known some kill’d on the Hilly Part of Cape-Fair-River, they passing the Ledges of vast Mountains from the said Messiasippie, before they can come near us. These Monsters are found to weigh (as I am informed by a Traveller of Credit) from 1600 to 2400 Weight.”

So with a bit of creative license, we might be able to postulate that an escaped “Messiasippi Buffelo” could have wandered down Spring Garden street a while back and been spotted by a scribe with pencil and paper at hand to document the occasion and honor the seepage with its namesake, but it’s a bit of a stretch.

The Buffalo Creek Canoe Club

There is, however, a trait that both beast and creek share that’s not much of an honor. Unfortunately for some of its neighbors, the creek, like its namesake, has at times given off a pungent reek that repels environmentalists and pleasure seekers alike. At one point, the pollution was so bad that Greensboro Record staff writer (and longtime O.Henry contributor) Jim Schlosser reported in 1971 that alleged sightings of minnows in the creek were so unlikely that “to anyone familiar with the stream, Martians in Jefferson Square would seem more believable.” He goes on to describe the creek as “long considered one of the State’s most wretchedly polluted waterways.” The cause he says, was Greensboro’s growing population and its effluents. Up until the ’40s, the mighty Buff was a popular and prolific fishing spot. But the South Buffalo Waste Treatment plant introduced its product to the stream, resulting in pollution and stagnation, virtually eliminating the former finned denizens. By the late ’60s, summertime pollution levels were so high that the stream’s oxygen content was measured at zero. The Buffalo released a mighty stench to go along with its oxygen starvation program, causing residents to berate city officials about cleaning up the creek, and in ’69, efforts started on what would become a decades-long journey to give the creek a cleanup and makeover.

Matkins and York got some attention to the cause back in 1980 with their city council bids. “Neither one of us got elected, but we did make a lot of changes. They had to pay attention to us,” York says. “The establishment was telling us we were radical and irresponsible. Ben and I watched the creek a lot because we were always around it and we would detect fish kills. We found syringes from Wesley Long hospital in the creek. There was a place out on Spring Garden Street on the other side of Holden — there was a chemical plant there — and they were dumping chemicals into Buffalo Creek, and it caused several fish kills, and we finally got that stopped.”

The duo got even more attention in the mid-1970s when they took a staff writer for the Greensboro paper, Bill Lee, on a canoe trip down the mighty Buff at storm surge tide all the way to the other side of Revolution Mills from their Hillcrest Drive home. But the attention came not from riding the scenic surge Lee documented with photos as well as text, but from a concerned citizen who thought the canoeing environmentalists were reckless as well as radical. “At the risk of sounding like a fuddy dud, I am compelled to comment on Bill Lee’s ‘Canoeist Careens on Buffalo Creek,’ an account of three youths canoeing the Buffalo in flooded stage,” Tom Berry wrote in on the Public Pulse section of the letters to the Record editor in July of ’75. Berry’s Fudd impulse was triggered by the callous youths’ alleged dare-demon attitudes. “I am afraid the article may well have put the idea into young heads who even now may be waiting for the rains to come,” he fussed. “While recognizing the need for youth to frolic and the unquestioned appeal of an opportunity in their own backyard, the flooded North Buffalo is no place for a canoe ride. Statistics of canoe fatalities are top heavy with just such innocent looking adventures occasioned by familiar shallow streams suddenly full of water.” He might just as well have added a harrumph or two for good measure. “I hope your youthful readers will not be induced to do so,” he wrote. “On the other hand, river canoeing can be a safe and sane recreation if approached reasonably, with the opportunity for as much excitement as one wants (and then some) when one has the skills for it.”

York’s wife, Suzanne, jumps to her husband’s defense, citing their expert handling shooting the tricky part under Revolution Mill where caissons await the careless and reckless, unfuddy canoers. “The caissons are going like this, and the water is going like this, and if you didn’t know what you were doing you’d run right into a caisson,” she says. “But they were experienced canoers.”

But even the inexperienced can and did shoot by them unscathed, if guided by pros. Matkins called this writer house one day just after a summer thunderstorm and said, “Let’s go canoeing.” And even though I told him I had no expertise in matters canoe, he said not to worry. He came and got me, and we set out down Buffalo Creek with a case of beer. It was pouring down rain. “Where are we going?” I asked. He said, “We’ll know when we get there.” So we just floated down the mighty Buffalo, sodden, but serene. Turns out I wasn’t the only beneficiary of the beer and Buffalo smorgasbord.

“One afternoon we were up at Ham’s and it was pouring rain and we were drinking and Ben said ‘I bet we could paddle Buffalo Creek right now, the water’s so high,’ says former city commissioner Joe Wood, a neighbor and friend of Matkins. “So we all got bundled up, went out, creek was up, got down near Cone Mills. Only one place we had to get out because of a pipe and that was down by Wesley Long Hospital.” After a brisk sojourn down the Buff, the sodden sailors, York included, retreated back to their watering hole and decided to give the outing’s participants a formal title for their watery shenanigans. “Ben christened it the Buffalo Creek Rainy Day Canoeing, Drinking, And Social Club,” Wood recalls.

Matkins’ daughter Brandye (Patterson) also navigated the Buffalo’s waters, but under different, and more sober circumstances. “When I was 8, my dad gave me a 10-foot Mohawk canoe for my birthday, and I remember paddling down Buffalo Creek,” she recalls. “We probably put in by the playground there at Lake Daniel Park. And I remember him holding on to the painter line as I paddled down the creek. He had custom-made a paddle for me, ’cause they were all too long. And he cut it down for me, put the paddle back on it, and it was just perfect.”

Brandye has a piece of memorabilia from her dad’s wilder Buff excursions. “I still have a homemade piece of art someone painted, I’m not sure who did it, of a Buffalo in canoe and it says the Buffalo Creek Canoe Club,” she says.

She also has vague memories of her dad working to establish a pocket park on the Buffalo over by Cone Hospital when she was small. “I don’t know specifics, my memories of that are being on that spot of land as a child and just hanging around while they were building a trail. I know there’s a picture of me and my dad looking out over that area, the caption talks about how this area is a work in progress, getting this area converted into the natural area it is now.”

Jezorek is able to provide more details. “It’s called the T. Gilbert Pearson Audubon Natural Area,” he says. “We’re still working on that. We’ve developed a system of trails.” Sometime in the late ’70s or early ’80s, an 11-acre tract owned by Cone Hospital was leased to the city of Greensboro for 99 years as a natural park. “We somehow got wind of that,” Jezorek says. “I don’t know whether it was Ben or who found that out, but we said ‘Hey, let us, Audubon, manage it for the city.’ So we have a contractual signed agreement with the City of Greensboro that Audubon will manage that natural area.”

The society has built a system of trails in the area over the years, installed picnic tables and benches, and is trying to remove invasive species as well as adding more native species. The Greenway, the work in progress that has made a maze out of downtown streets recently, will eventually meet up with it. “The trail that runs through Lake Daniel and Latham Park, which now ends at Elm Street is now to be extended along Tankersley Drive — that’s the street that runs between Elm and Church — on the south side of Tankersley where there’s a sidewalk,” Jezorek explains. He says the trail will continue “through the natural area, either over Church Street or under, following the creek over to Revolution Mill, then out to the northeast part of the city, hopefully in our lifetime.” The society uses the natural area for educational and recreational purposes, and sponsors the Great American Cleanup the first of April, with volunteers and members going down in the creek and pulling out trash.

It’s been a long process. Matkins, York, Wood and Jezorek, as well as many of their neighbors along the waterway lobbied the city for years to let the creek be more natural. “We had the notion that they shouldn’t be mowing the banks and all the vegetation around the creek for a whole lot of reasons,” Jezorek says. For one thing, vegetation shades the water, keeping it cooler. “We had a lot of fish kills in those days — the city mowed everything,” Jezorek says. “There was not a tree, not a shrub, nothing.” He calls it a “a biological desert,” because in shallow creeks in the summertime, the temperature goes way up and the oxygen gets depleted. That, not pollution, was killing the fish. Shading is a simple and effective solution. The efforts of former Mayor Allen, The Audubon Society and the Westerwood neighborhood, finally brought progress in reviving the Buffalo in the early ’90s. The groups studied the programs of four forward-looking states — Colorado, Florida, Maryland and Oregon — that had taken steps to care for their waterways and introduced similar programs and policies to Greensboro.

“The city manager was Ed Kitchen, a really good guy, still involved with Action Greensboro, and Carolyn was mayor, so it was the best of circumstances,” Jezorek says. “We set up with the city and with Westerwood a pilot project to let the banks grow up, did some work putting some rocks and things in the creek to provide some ripples and get some oxygenation going.” It took a decade or more, he says, but finally, “bowed out and the city actually came up with a policy of its own. Our effort predated the city’s storm water division.” The project made tree-huggers out of a bunch of Buffalo denizens. “Now, if anyone wants to remove a tree in the buffer along the creek, the neighborhood gets up in arms. We did all kinds of education presentations in the neighborhood. It’s become part of the community as it is all over town. That postdated Ben, but he planted the seeds in a bunch of our minds.”

Princess Whitewater Lives

Another seed that Matkins planted resulted in a raucous pageant and free-for-all that made cross-dressers of Greensboro’s straightest citizens under the guise of raising money for charity with a Buffalo-themed annual ball crowning Princess Whitewater. “Again, it involves drinkin’,” says Wood, who had Matkins for his campaign manager. A bunch of friends had gathered on Matkins’ back patio just after the Greensboro Debutante Ball had just taken place at Blandwood. “And we said, by Gawd, why don’t we have a neighborhood party for all our daughters who are never gonna be invited to be Debutantes and have a party for ourselves and our daughters, introduce them to society? So we thought on it a little more and drank a little more, and said ‘Why don’t we have a men’s beauty pageant? And why don’t we do it for charity?’”

That twisted logic sounded pretty good at the time, but proved to be a hard sell in the sober light of day. “Nobody wanted to dress up in women’s clothes at that time, which was 1980,” Wood says. But the group forged ahead, renting Blandwood, hiring a band, inviting around 600 people, getting several local bars to sponsor them. There wasn’t a pageant the first year, but the affair got an unexpected boost from an impromptu parade for the occasion. “Bill Eckard agreed to play the role of Princess Whitewater, put on a pink shift and a Minnie Pearl hat, put a canoe on top of Ben’s van, and we all gathered in front of Tiajuana Fats, on Federal Place. Had the Buffalo Creek Marching Kazoo band, and Bill Eckard was the princess on top of the float,” Wood says.

From then on, people got in line to be a Princess Whitewater contestant. “We started doing it the next year, ’81, which was the second Princess Whitewater — had about 10 or 12 bars in Greensboro to sponsor candidates, Faye Nelson from the Ritz [Costumes] helped everybody get costumes. It was raunchy — helped to have some stomach and some facial hair.” Wood estimates a crowd of 500 showed up, paying about $8 for admission and a chance to gape at local celebrities in drag. “I remember Forest Campbell, head of the County Commissioners, was there, in a tuxedo jacket and a pair of those boxer shorts with the Valentine hearts on ’em, and was on roller skates. Everybody, from millworkers to CEOs of big corporations in Greensboro, was there. We raised about $2,000 and donated it to charity. I have no idea what the first charity was but the nine years we actually had a pageant we raised about $25,000 for charity.” Beneficiaries included the Audubon Society, Sierra Club, Friends of the Carolina Theatre and the Retinitis Pigmentosa Foundation.

Princess Whitewater crown-wearers included Stan Swofford from the Daily News, the first Princess Whitewater when a pageant was held. “Kent Hoffman from the Costume Shop downtown was a princess, I was a princess. When we had the final Princess Whitewater in 1989, we had the Princess of the Decade and Bill Eckard who was the original princess won the thing. Lots of incriminating photos. Ogi Overman was a Princess Whitewater, Harry Murr. That’s as much as I can tell you without telling you all the trash.”

A Creek Reborn

These days, just like the folks who shared their memories with us, the Buffalo is all grown up. “Best thing that happened to that park is those trees coming up in there,” York says. “That’s attracted a lot more wildlife. I’ve got some neighbors here who tell me that deer won’t come into the city. I tell ’em ‘Do you think deer stop at the city limits sign and turn around and walk off?’” There have been deer sightings at the Pearson park tempting some to invite the shy animals to dinner — as the main course. “There was a big write-up in the paper about a bear being down there,” York continues. “And we’ve seen herons down here, and they have hawks and ducks, the mallard ducks, falcons,” Suzanne York adds. There have also been reports of groundhogs, muskrats and beaver. But the elephant in the room is the mighty buffalo — still no signs of the scruffy, unruly, but noble creature that lent its image and in days past, its aroma to the creek. It’s wandered on, back to the Messiasippi perhaps, or parts unknown. But its spirit lives on, wild, wooly and wondrous, in the creek that proudly bears it name. OH

From his hilltop home, Grant Britt gazes longingly at the mighty Buff on stormy days, but has learned his limitations over the years and is content to be up the creek without a paddle.

“

“

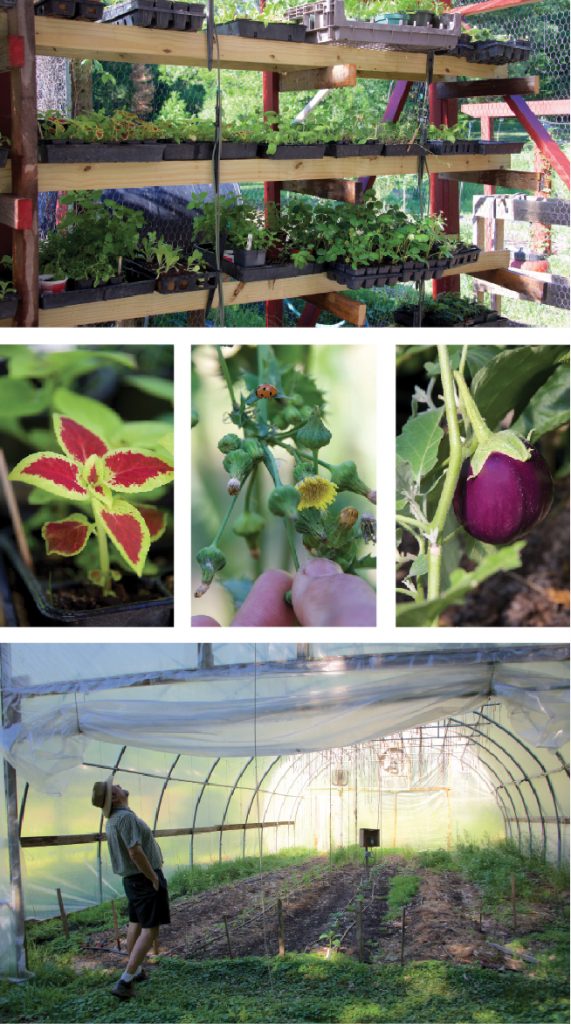

If Stephen Johnson’s Australian accent didn’t give away his homeland, his Aussie-made Akubra hat might.

If Stephen Johnson’s Australian accent didn’t give away his homeland, his Aussie-made Akubra hat might.

Nothing goes to waste, be it produce or experience. If crops succeed, they go straight to table or market. If not, they — and the weeds — go to the chickens that Johnson tends, on his property, with a neighbor.

Nothing goes to waste, be it produce or experience. If crops succeed, they go straight to table or market. If not, they — and the weeds — go to the chickens that Johnson tends, on his property, with a neighbor.