The Nature of Things

Imaginary Worlds

By Ashley Wahl

It’s hard for me to let go of a good book, even when I’m sure I won’t reread it. Yet each time I pack up and move, my shelves receive a thorough sweep.

Last summer, before leaving my former home in Asheville, I wistfully delivered a trunkful of classics to the Little Free Library up the hill. If I wanted to read The Catcher in the Rye again, I could always make a trip to an actual library — assuming they’d reopen some day with the rest of our then-shuttered world.

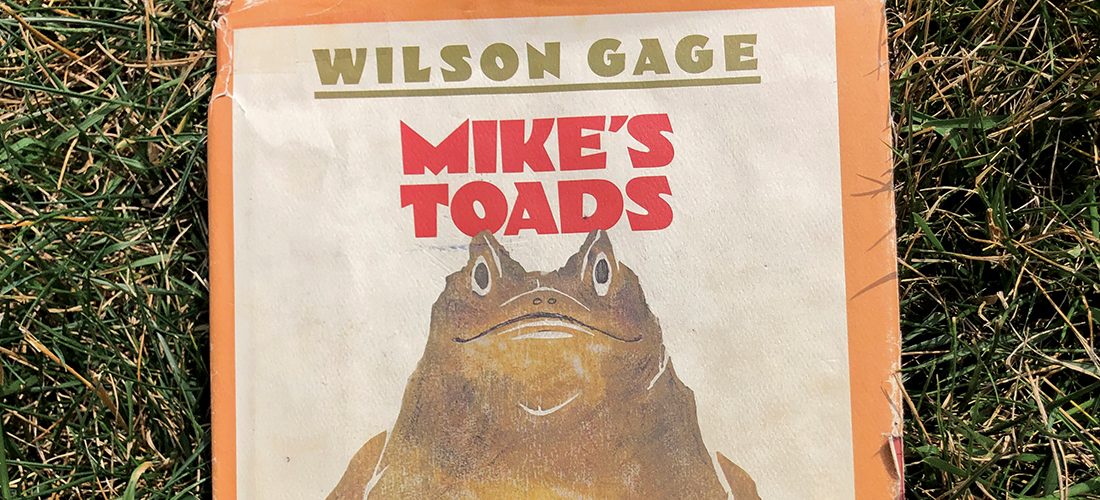

These days, my bookshelves are mostly stocked with poetry and favorite memoirs. But there’s one book from my childhood that somehow keeps making the cut. Tediously mended with small strips of Scotch tape, the dust jacket suggests that Mike’s Toads must have been a favorite read, although I couldn’t quite tell you why.

Maybe it was the art.

On a recent summer afternoon, I took the book from my shelf, went outside and studied the cover illustration of a fat, smug looking toad the size of my adult hand, half wondering if it might blink. Written by Wilson Gage (pen name of Mary Q. Steele) and peppered with primitive sketches by illustrator Glen Rounds, Mike’s Toads was a gift from my grandparents on my 7th birthday. Not that I had remembered that. But when I cracked the book open for the first time in nearly 30 years, I found the inscription from Mammaw and Buddy.

Beneath the shade of a black walnut, our panting dog stretched out like a treasure map beside me, I stepped inside a long-forgotten world in which a boy named Mike learns a thing or two about toads and life. (Spoiler alert: If your brother can’t watch the neighbor’s toads for the summer, but you tell the neighbor that he can, then guess who’s watching the toads?)

As I turned the pages, tickled by expressions like “Oh, good grief” and “For Pete’s sake,” I couldn’t help but think back to a simpler time.

Until I was 7 years old, my kid brother and I shared a bedroom and virtually everything in it. But once my parents bought their first house — a modest ranch surrounded by towering pines — our bunk beds went into Kris’ room, and I moved into a space of my own. After lining my shelves with stuffed animals and miniature plastic horses, I promptly cleared out my closet to create a secret reading fort, an imaginary world that might take me anywhere.

While I doubt that I ever shared my closet hideaway with my brother, we still shared plenty of things, including a shoebox filled with tiny rubber lizards, each animated with a name and a story, hatched from the 50-cent machine on grocery runs to Food Lion. Fortunately for my parents, we never felt the need to bring home real ones. Unless my brother had a secret that I still don’t know about.

As dappled sunlight danced across the final pages of my little book, the sleeping dog chased her own imaginary critters, and life felt simple.

And as the sun dipped further still, the faintest kiss of autumn arrived on a summer breeze.

Good grief, I thought to myself. Where does the time go? OH

As a child, editor Ashley Wahl was wild about the Teddy Ruxpin books. You can contact her at awahl@ohenrymag.com.