A WAY OF LIFE

A Way of Life

Ann Tilley makes her mark, as lightly as possible

By Cassie Bustamante • Photographs by John Gessner

For me, it’s always been just to have the lightest impact on the world, on nature,” says Ann Tilley as she peers out from her sewing studio’s garage door, surveying the acreage that surrounds it. Nearby sits the narrow, tiny house with wood siding she and her husband, musician Adam Joyce, built and now reside in. The large family property is just about as far southeast as you can get in Guilford County. Just behind their home, a row of raised garden beds made from old refrigerators host early spring plantings, such as garlic, protected from the couple’s curious cats. Clothing pinned on a line strung along the garden’s exterior border waves in the breeze.

Tilley pauses, her fingers gently gliding along a patchwork T-shirt in shades of green with touches of lilac. “This is my absolute favorite shirt.” The garment has been created by stitching together pieces from old band merch. And not just any band — The Bronzed Chorus, Joyce’s group, whose sound is, according to Tilley, “instrumental post-rock, but then there’s a lot of synthesizer and electronic. I always say that if you listen to it in your car, you want to speed.” Tilley made a dozen or so of these tees and sold them at the band’s shows. The couple originally met at a Bronzed Chorus show in Durham, where Tilley was raised. Today, both are employees of Forge Greensboro. Joyce, a woodworker and furniture maker by trade, runs the makerspace’s wood shop while Tilley runs the textile shop.

Back in Bull City, Tilley’s parents own and run Acme Plumbing Company, originally founded by her great-grandfather. While her mother owned a sewing machine, Tilley, now 38, says the actual use of it sort of skipped a generation. “It was not progressive for her to sew,” she muses. Instead of traditional toys, Mom bought the kids sketchbooks and markers, nurturing creativity in other ways, while at the same time instilling in them environmentally conscious values.

“My mom was the first person I ever knew who wouldn’t buy something because of the packaging associated with it — before I ever heard of zero waste,” says Tilley.

Tilley recalls latching onto cross stitch as a child via Girl Scouts, discovering she loved fabricating art from fibers and how embroidery floss felt on her fingers. Later, in her tween years, a household book she happened to pull from a shelf opened her up to the world of sewing.

Foot to the pedal, she unearthed a means to express herself. “I like to be different,” she says. “I don’t like to wear what other people wear.”

Still, as the child of practical, no-nonsense parents, she says, “I thought fashion was frivolous. My parents are plumbers.”

Tilley’s interest in the arts led her to the Savannah College of Art and Design, a move that she says was good for her because it allowed her to explore painting, drawing, illustration and fashion. By the time she was an upperclassman, “I was obsessed with fashion magazines,” she recalls. “Harper’s Bazaar was my bible!” Tilley would flip through pages and, inspired, make her own versions of what she saw.

Her fashion interests led her to discover the fibers department, something she didn’t even know had a name. She recalls someone explaining to her what that department entailed and realizing it was exactly what she’d been after — “That’s me!” she recalls exclaiming. In 2008, Tilley graduated with her Bachelor of Fine Arts in fashion and fibers.

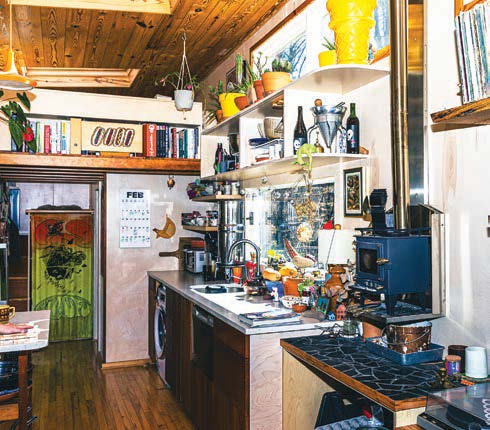

These days, Tilley calls herself a textile artist. The light-wood walls of her tiny home are filled with her own creations. “Pop art was my first love, which I think is really obvious.”

The art that hangs on her walls makes the house into something of a tiny museum that catalogues Tilley’s evolving interest in textiles. Inside a large, charcoal-gray, curved frame mimicking the shape of an iPhone is a woven textile she calls Hold Me, which is exactly what the text on the piece beckons. On the adjacent wall in the tiny home’s single spiral staircase leading to the loft, a complementary creation titled Current Reflections is framed in wood salvaged from old bleachers and given to them by a Forge friend. The piece itself is a chartreuse green, the yarn dyed by Tilley, and features a motif of toothbrushes, solar panels, poison ivy, trees and, in the center, tiny homes.

Up in the loft, the couple’s platform bed sits below a skylight. A shelf, inches away from the foot of the bed and made from the same recycled bleacher wood, provides ample room for books, plus space for guitar cases below. “It’s a little bit of a pain in the ass to change the sheets, but . . . ,” she trails off dreamily, looking up.

“I can literally see the Big Dipper,” she says. “And when you wake up in the middle of the night and the moon is there, I feel blessed every time.”

Next to the bed, a wall hanging Tilly fabricated faces the wrong direction so that the couple’s brindle-coated kitten, Tina — short for Patina — won’t damage it. Tilley takes it down and Tina immediately attacks.

The hanging is one of several Tilley made during a three-week art residency at Reconsidered Goods last November. Using denim yardage unearthed in “a ’70s storage unit,” Tilley crafted a piece that pays homage to Greensboro’s history in garment making, as well as her own background working as a Wrangler traveling on-site tailor and at a Raleigh denim factory. A pocket on the hanging is adorned with a leather Wrangler patch and Ralph Lauren rivets, a spray of bright, printed and embellished flowers emerging. Hot-pink felt lettering reads “Feeling lost? Discover crafts.”

“All of these pieces came from the idea of craft as therapy,” says Tilley of the work that came out of her residency.

Back downstairs on a gallery wall, a hanging fabricated from necktie silk reads “Days for Making, Days for Mending,” a necktie Tilley sewed hanging down its center. Along the bottom of the piece, “Salem” tags create a sort of fringe effect. Last fall, Tilley toured Salem Neckwear with Rene Trogdon, who was selling off and donating machinery and materials. His late father, James Trogdon Sr., had founded the company in 1964 to fill a niche market for premium neckties. Sixty years later, after Rene’s brother and the company’s then-president, James Trogdon Jr., became ill with long COVID, Rene found himself in a tough position and had to close. Sadly, James Trogdon Jr. passed away in December of last year.

“I mourn those stories of the loss of small and local,” she says, noting her parents’ own multigenerational company. Creating art with remnants from businesses such as Salem Neckwear, she gets to preserve a piece of their story.

“The thing I fear the most,” she continues, “is just that globalization is taking away all of that local personality.”

Every corner of their house, almost every nook and cranny in it, veers away from mass merchandising and designs driven by big-box retailers such as HomeGoods and Home Depot. The sliding door that leads to their single, green-tiled bathroom is a remnant from Tilley’s childhood bedroom. Where the original hardware sat, Joyce created darker-stained, midcentury-inspired wood inlays that flank the new nickel hardware. The exterior panels have been covered with mirrors to reflect light, giving the illusion of space. But the interior of the door was not such an easy task. Tilley struggled to strip all of the paint and eventually settled on covering it with a pastoral mural.

“I thought it was going to be done in a year without me doing anything,” quips Tilley about the home’s construction. But, she soon realized, “we need to do this together.”

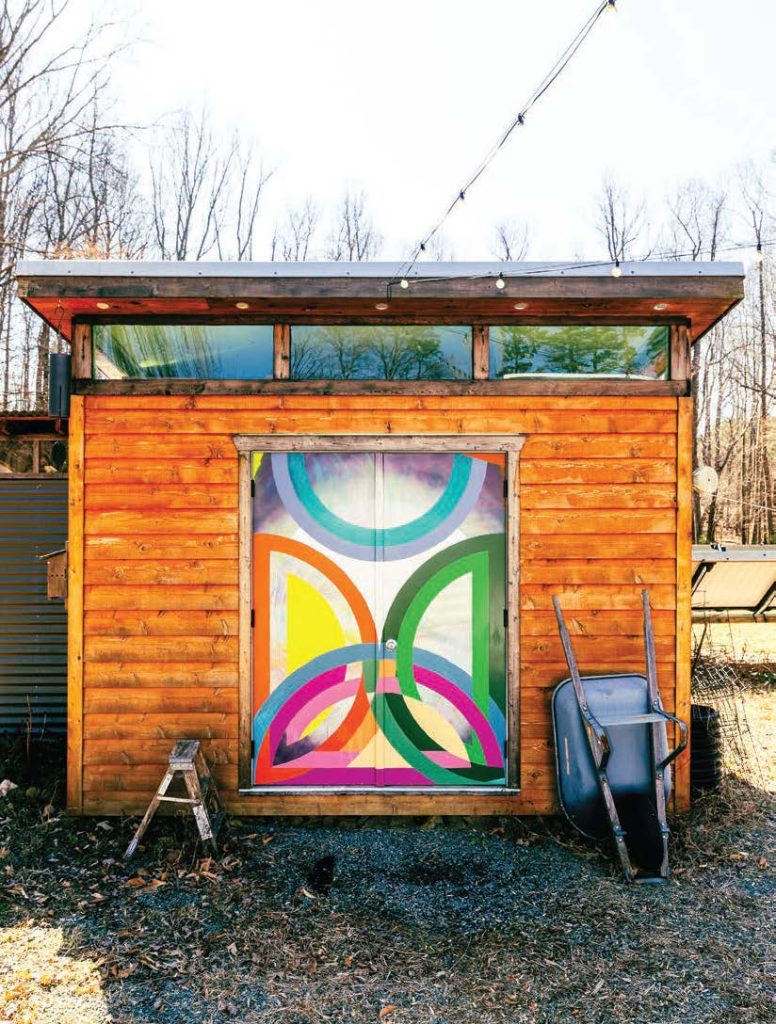

Over the course of almost a decade, whenever they had time, Tilley and Joyce could be found outside of their rental home, just down the road in Julian, measuring, cutting, hammering. They also regularly visited the property, which had been in Joyce’s family for generations, first building and installing a solar shed.

The doors to the shed feature a modern graphic design in vibrant colors, inspired by a Frank Stella piece. Stella, who passed away in May of last year, was known as one of the fathers of 1960s minimalist art. Tilley and Joyce painted the doors right after a particularly busy moment in life, “and then, on our week off, we were like, ‘Let’s do something fun.’” A moment later, she chuckles. “We can’t ever relax.”

Beyond its bold doors, the building houses the tiny home’s breaker box and a generator, plus the regular tools one would expect to find in a shed. As far as the solar system that runs the property’s power, Tilley says, “Adam just watched a bunch of YouTube videos” and figured it out.

Some yards away from the home, a curved hangar featuring a bold, turquoise garage door serves as her sewing studio. It’s not heated though, so she has plans to construct a new building and has marked stairs with old sewing machines leading to where it will exist a stone’s throw away. “Manifest destiny, you know?”

“Right now, it’s a little nippy,” Tilley says. She tugs tighter around her a lavender velvet jacket she made with a cherry-printed lining, all fabric sourced from Reconsidered Goods.

This is where the real “magic” Tilley is known for happens — Magic Pants, that is. In 2016, Tilley founded Ann & Anne, a ready-to-wear clothing brand, with Anne Schroth, owner of Red Canary. While there, the two women designed a high-waisted tailored pant that featured an invisible elastic band in the back, an elastic panel in the front, and a cinching strap. The result? A pant that flattered figures of all shapes and sizes. Her friends started calling them “Magic Pants” and the name stuck.

Ann & Anne closed officially in 2018 and Tilley pivoted to teaching sewing classes across the area, from Durham all the way to Winston-Salem, including a stint at the John C. Campbell Folk School in Brasstown.

At Village Fabric Shop in Winston-Salem, she offered a class on making Magic Pants and the shop employees suggested that she make a pattern for them. At the time, she was busy teaching, but when COVID shut that down for a while, she got to work. And now? “I have literally sold this [pattern] on six continents.”

Tilley has also created her own YouTube channel, which allows her to increase her reach, teaching people across the world how to make these pants. Sewing, she says, is what gave her the “first feelings of self-sufficiency,” something she hopes to pass on to others through her instruction. Nowadays, she makes practically everything she wears, right down to the undies, something she started making from scraps when she worked at Gaia Conceptions, a sustainable brand founded by Andrea Crouse and located “just behind Westerwood Tavern.”

“I worked there for years,” says Tilley. Gaia Conceptions, she says, features made-to-order organic clothing and the brand pays its employees fairly. “They really walk the walk.” Crouse, Tilley says, even showed her how to make her own deodorant.

Nearby, a pair of of underwear in blue and white sits on her sewing table. “I haven’t worn these — don’t worry” she quips. The fabric is soft, comfortable, and there’s no elastic that would dig into a waist.

While the temperatures have been less than ideal, Tilley has, for now, set up shop in Joyce’s music studio, settled a little farther back on their land. A makeshift desk in the middle of his space holds her Brother sewing machine, a row of guitars hanging on the wall behind it. Next to the machine, old fashion drawings from her SCAD days feature a flirty midi dress, a long embellished gown and a mod ’60s-inspired swimsuit. “I do make my own swimsuits now,” she says. “And having a well-fitting swimsuit is wild!”

Joyce’s studio serves as the hangout spot for the couple’s other cat, Go-Go Boots, a beauty with long fur everywhere except for — you guessed it — below her knees. With the sun beckoning, she requests to go outside. Tilley follows.

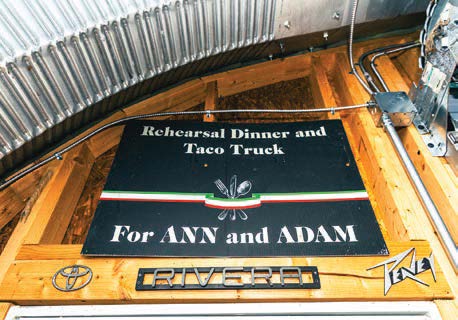

“We actually got married in this field,” she says, looking out into a large, cleared space of land. In July of 2016, the couple tied the knot. True to form, the large tent that provided shade for guests was made by a friend “from old Tyvek he dumpster dived.”

And do they plan to live out their days where they once said “I do”?

“Forever home, absolutely,” says Tilley. Perhaps, one day, they may consider building a different house with a main-level bedroom as they age. But, if they do, it will be right here. “It’s a way of life.”