The Last Ballad

Wiley Cash creates a model for other writers

By D.G. Martin

Readers of this magazine have come to know and admire Wiley Cash as a regular contributor of poignant essays about his family, his work, and his writing.

In the October issue, he gave us a very personal report about the origins of his latest novel, The Last Ballad. He told us that for the past five years he had been “living in a 1929 world of cotton mill shacks, country clubs, segregated railroad cars, and labor organizers with communist sympathies. Everything I know about the craft of writing and the history, culture and politics of America, especially the American South, has gone into this novel.”

Now that the book is out and Cash’s promotional book tour is drawing to an end, it is a good time to take another look at this remarkable story of blended fiction and important history.

When Cash takes us back to 1929 Gaston County’s textile mill country, he forces us to confront real and uncomfortable facts about the brutal conditions workers faced. All the while Cash uses his storytelling gifts to create a moving tale about a real person, textile worker and activist, Ella May Wiggins.

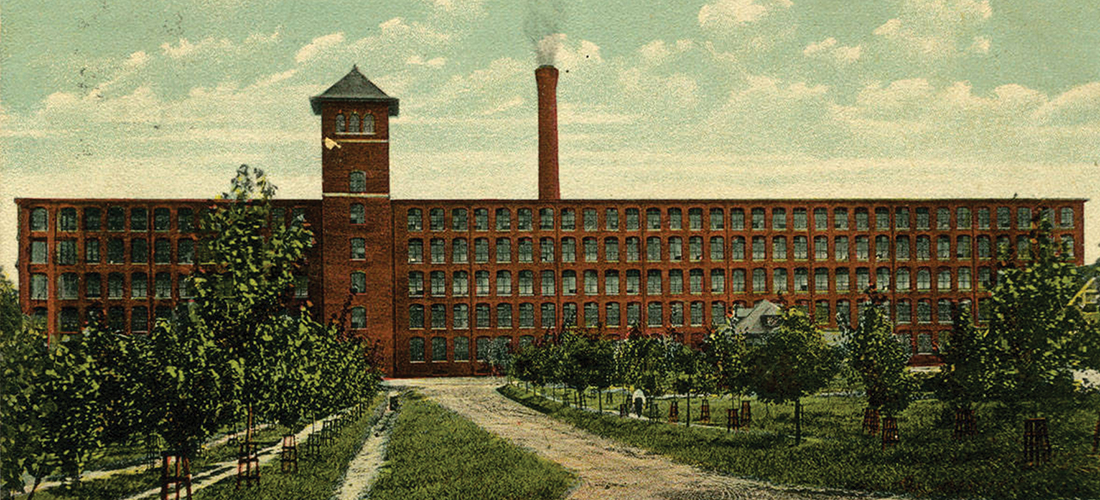

On the frame of this real character, Cash builds a moving story that puts readers in Wiggins’ shoes as she walks the 2 miles every evening from her hovel in Stumptown to American Textile Mill No. 2 in Gaston County’s Bessemer City, works all night in the dirt and dust and clacking noise, and then walks back to tend to the children she has left alone the entire night.

Cash follows her decision to support the strike at Loray Mills, where her ballad singing at worker rallies mobilized audiences more than the speeches of union leaders. He relates how her actions also provoked negative responses from union opponents that led to her death.

In the book’s powerful fourth chapter, Cash compresses the conversion of Ella May from oppressed textile worker to inspirational union hero into one evening. As she rides in the back of a truck from Bessemer City to a pro-strike rally at the Loray Mill in Gastonia, she tells Sophia, a union organizer, about her family’s struggles, the death of her beloved son, and “the weight of her children and their lives upon her heart.”

“Hot damn,” Sophia says. “And you sing too?

“Hell, girl, we hit the jackpot with you. You might be the one we’ve been looking for.”

That evening in Gastonia, in the shadow of the “colossus of the Loray Mill . . . its six stories of red brick illuminated by what seemed to be hundreds of enormous windows that cast an otherworldly pall over the night,” Ella May tells her story to the rally’s crowd and sings a song from her mountain youth that she adapted on the spot.

She began,

“We leave our home in the morning,

We kiss our children good-bye.

While we slave for the bosses,

Our children scream and cry.”

And after several more verses of struggle and woe, she concluded,

“But understand, dear workers,

Our union they do fear,

Let’s stand together, workers

And have a union here.”

When it was over, “people cheered, whistled and pointed, called her name and chanted union slogans. Flashbulbs popped and illuminated ghostly white faces as if lightning had threaded itself through the audience.”

By the end of the evening and the conclusion of the fourth chapter, Ella May has the makings of a legend and a target of the anti-union forces that will bring about her early death.

In the book’s other chapters, Cash introduces us to people who shaped Ella May’s life: her no-good husband John, her no-good boyfriend Charlie, the Goldberg brothers who ran the mill where she worked, her African-American co-worker and neighbor Violet, the union strike leaders, a 12-year-old worker who loses half his hand when it gets caught in the mill’s machinery, and Wiggin’s children as they struggle through hunger and illness.

We also meet an African-American railroad porter, Hampton Haywood, a communist union organizer. Ella May makes an unlikely friendship with Katherine, the wife of mill owner Richard McAdams. Katherine persuades her husband to sneak Hampton out of town to save him from a racist and anti-union lynch mob, risking Richard’s place in the elite social order — and his life.

The picture Cash paints is an ugly one, showing conditions of Wiggins and her fellow workers to be only a step or two away from serfdom and slavery.

Education for the workers or their children was a pipe dream, as Wiggins explained to U.S. Senator Lee Overman, when the union sent her to Washington to tell the union story. Overman had told a striker she should be in school.

“Let me tell you something,” Wiggins shouted at Overman. “I can’t even send my own children to school. They ain’t got decent enough clothes to wear and I can’t afford to buy them none. I make nine dollars a week, and I work all night and leave them shut up in the house all by themselves. I had one of them sick this winter and I had to leave her there just coughing and crying.”

In his first two best-selling novels, A Land More Kind Than Home and This Dark Road to Mercy, Cash had wide freedom to develop compelling stories and fashion endings that would surprise and satisfy his readers. But he lost this freedom with The Last Ballad. Historical fiction binds its authors to certain facts. There can be no surprise ending. Cash’s readers know from the first page that Ella May is going to be killed.

In Cash’s case, however, the genre does not restrict his great gifts in character development or in developing rich subplots that give his readers a satisfying literary experience. As a bonus they come away with a deeper comprehension of Ella May’s experiences and those of the people on all sides of the Loray labor conflict.

In his October article for this magazine, Cash, who grew up in Gastonia, explained what made writing about Wiggins a difficult task. “How could I possibly put words to the tragedies in her life and compress them on the page in a way that allowed readers to glean some semblance of her struggle?”

Recently he told me, “I wanted to write a novel that was not only true to the facts, but I wanted almost more importantly to write a novel that felt true to the experience as I understood it. When I was writing this novel I was perfectly aware that these are real events. And the facts are all there. The facts in this novel, are indisputable. And I felt like, by getting the facts right, it allowed me a scaffolding to let the characters come alive.”

So how did Cash do?

I agree with Charlotte Observer writer Dannye Romine Powell, who called The Last Ballad Cash’s “finest” novel, one that she suspects “will serve as a model for any writer who wants to transform fact into fiction.”

In creating this model for other writers of historical fiction, Cash met his challenge of putting into words Wiggins’ tragic life and the oppressive times in which she lived.

And those words and the story they tell confirm Cash’s place in the pantheon of North Carolina’s great writers. OH

D.G. Martin hosts North Carolina Bookwatch, which airs Sundays at noon and Thursdays at 5 p.m. on UNC-TV.