Almanac December 2020

Almanac

By Ash Alder

December is here and, with it, the sound of a single cricket. One distant, mechanical song. A message transmitted across space and time.

The stars are out. You cannot sleep. And so, you listen.

Months ago, when the crape myrtle scattered her crinkled petals like pink confetti upon the earth beneath her, an orchestra of crickets filled the night with a song thick as honey. And months from now, when the vines are heavy with ripening fruit, they will sing again, knitting an afghan of sound by moonlight — gently tucking you into bed.

On this cold December night, the cricket transmission grows clearer. You follow it like a single thread of yarn until you receive it:

There is no end, the cricket sings. Only change.

Somehow, this message brings you comfort.

December isn’t an abrupt or happy ending. There is no hourglass to turn. No starting over. Just a continuum. An endless stream of light and color ever-shifting like a dreamy kaleidoscope.

December is sharing what’s here: our warmth, our abundance, what we canned last summer.

This year and the cold have softened us. We feed our neighbors, feed the birds, open our hearts and doors.

The camellia blossoms. Holly bursts with scarlet berries. From the soil: gifts of iris, phlox and winter-flowering crocus.

The cricket offers his song — a tiny thread guiding us toward the warmth of spring — and we listen.

This listening, too, is a gift. Sometimes it’s all we’ve got. And, sometimes, that listening is itself a simple thread of hope.

December’s wintry breath is already clouding the pond, frosting the pane, obscuring summer’s memory . . .

– John Geddes

You Gotta Eat Your Spinach, Baby

Fortunately, many nutrient rich greens thrive in our winter gardens. Especially spinach. And what’s not to love about it?

Enter pint-sized Shirley Temple, ringlets bouncing as she marches past a small ensemble to join Jack Haley and Alice Faye centerstage:

“Pardon me, did I hear you say spinach?” she asserts with furrowed brow and her punchy, sing-songy little voice. “I bring a message from the kids of the nation to tell you we can do without it.”

And then, song:

No spinach! Take away that awful greenery

No spinach! Give us lots of jelly beanery

We positively refuse to budge

We like lollipops and we like fudge

But no spinach, Hosanna!

And now for the opposing view: In the 1930s, the spinach industry credited cartoonist Elzie Crisler (E.C.) Segar and his muscly armed sailor man for boosting spinach consumption in the U.S. by 33 percent.

But why-oh-why did he eat it from a can?

Longer shelf life, no doubt. Also, cooked spinach contains some health benefits that raw spinach does not. Raw spinach is rich in folate, vitamin C, niacin, riboflavin and potassium, but it also contains oxalic acid, which can hinder the body’s absorption of essential nutrients like calcium and iron.

According to Vegetarian Times, eating cooked spinach allows you to “absorb higher levels of vitamins A and E, protein, fiber, zinc, thiamin, calcium and iron.”

In other words: You gotta eat your spinach, baby.

O.Henry Ending

The Rebel in Me

A gourmet’s shameless confession

By David Claude Bailey

Whenever, as a teenager, I would do something that was beyond stupid, as in outright illegal, like seeing if our Pontiac Bonneville would really go 120 mph with my tattletale sister in the car, my dearly departed father would let out a long sigh and say, “Son, do you have some sort of predilection for institutional food?”

This was characteristic of my old man’s cutting sense of humor, but yes, Dad, I have, in fact, developed a penchant for institutional food over the years.

Despite my winning the N.C. Press Award for writing about fancy, white-tablecloth dining in the Triad, a smorgasbord of comfort food makes me lick my lips just by naming them: mac’n’cheese, scooped upon request from the corner of the hotel pan where it gets those exquisite crusty edges all caramelized into gooey bits; chicken-fried steak painted with a layer of creamy milk gravy; turkey with gravy and cranberry sauce, served out of the holiday season; meatloaf featuring tangy notes of sage from the breakfast sausage blended into it, covered with fire-engine-red chili sauce; salads — Watergate, Waldorf, Greek and tomato-aspic; and — my oh my, pie: goopy coconut-cream pie or tart Key-lime pie made from sweetened condensed milk.

Unlike many kids, my introduction to institutional food was a fortunate one, at South End School in Reidsville where the servers (who were also the cooks) pitied the skinny little boy in front of them with his big brown eyes fixed on the sizzling, chicken-fried steak. We quickly got to know each other on a first-name basis and they would always give me generous servings.

“David,” the sweet voice of the server would whisper alluringly, “Wouldn’t you like a little leftover dish of yesterday’s spaghetti-and-meat-ball casserole? We saved some just for you.”

I’ve also had some terrible institutional food, perhaps the worst at Boy Scout camp, where you could hoist your wiggling serving of cold grits onto the end of your fork and heave it across the table. But growing up in the food desert of Reidsville, I relished trips to Greensboro and Charlotte, which introduced me to the wider world of exotic cafeteria food, such as the chicken chow mein served with crispy noodles drowned in soy sauce at Greensboro’s downtown S&W Cafeteria near Belk.

I never served in the military, but I sure have been served some superb food by various branches of the armed forces: incredible picnic fare at Camp Lejeune on a Boy Scout Jamboree; fabulous oven-fried potatoes and roast beef on a Navy ship while I was a reporter covering missile launches from submarines at sea; hearty, stick-to-the-ribs fare at Parris Island, where I followed a Marine recruit through basic training; and a first-rate steak dinner I ate in the officers’ mess aboard an aircraft carrier on a shakedown cruise.

Perhaps the best institutional food I ever had was when I taught at Salem Academy, meals cooked with love and devotion by Helen Sowers. Her perfectly crisp fried chicken might just have been enhanced by Salem’s rule that you had to eat it with a knife and fork, the same way you were supposed to eat potato chips. (You could eat a hot dog with your hands, but several teachers insisted on cutting theirs in two first.) Mrs. Sowers’ desserts were legendary: chess pie that made me miss my mother; pound cake laced with so much butter its aroma beckoned you to take a bite before you finished your meal; and Hello Dollies, made devilishly rich with coconut, chocolate, condensed milk, pecans, graham crackers and who knows what else.

My most recent love affair with institutional food was at Moses H. Cone Memorial Hospital, where I ate nearly every weekday for years since it was across the street from where I worked at Pace Communications. This puzzled some of my colleagues who typecast me as a gourmet food-snob, a pose I’d adopt when I wrote about the restaurants of Rome, Paris and New York for Sky magazine. But I would also wax rhapsodically about pit-cooked barbecue or Cincinnati chili I found in airport cafes.

So I guess Dad’s words were both prophetic and prescriptive. I have, in fact, developed a predilection for institutional food. And it’s probably by his counsel that the institutions where I’ve enjoyed them have not been behind lock and key. At least so far. Thanks, Dad. OH

David Claude Bailey is a contributing editor for O.Henry magazine

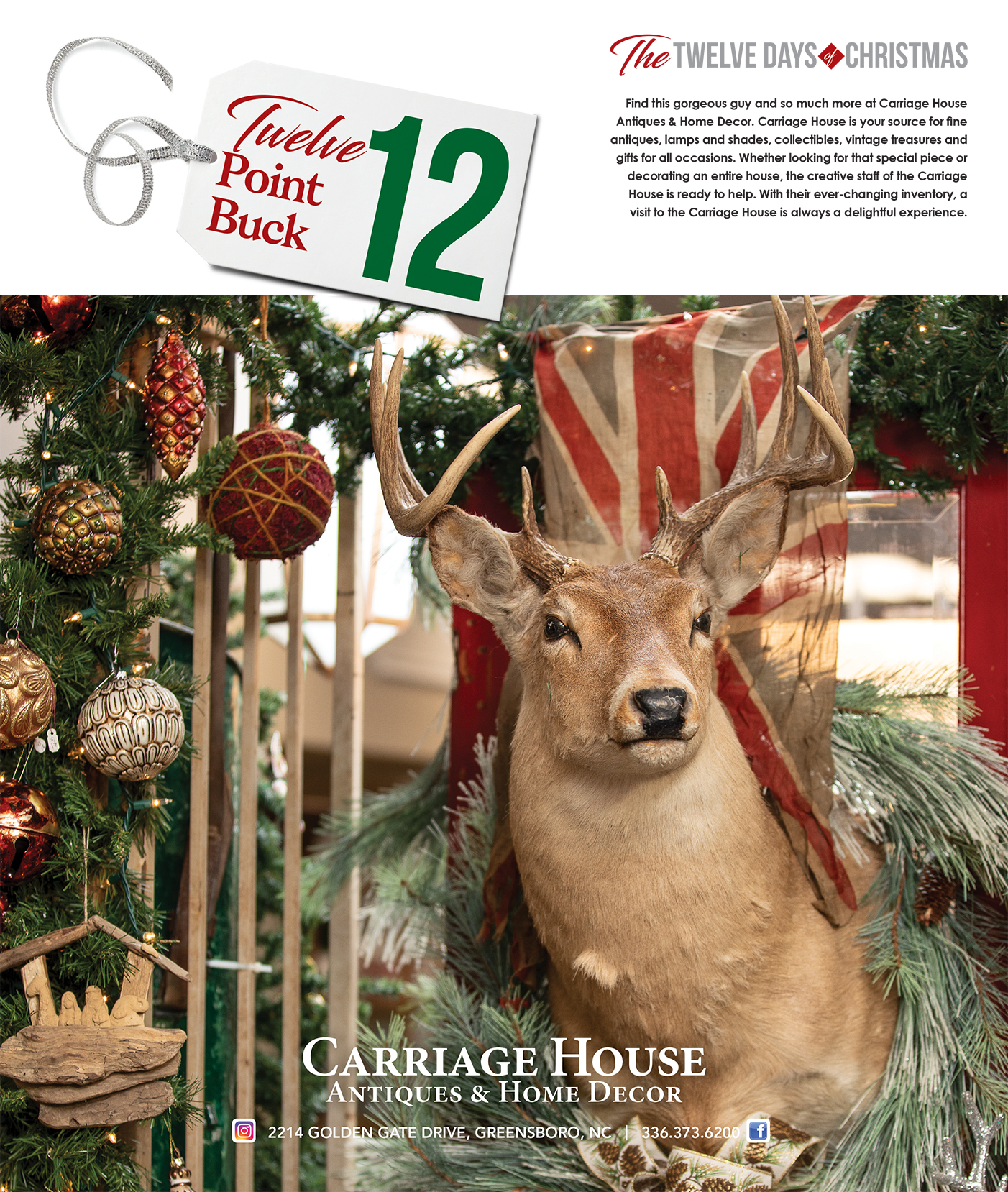

Christmas on Tate

It’s cozy, over the top and perfectly holly jolly

By Cynthia Adams • Photographs by Amy Freeman

Grumps and Grinches beware. To enter Katrina and Nat Hayes’ College Hill bungalow is to have a holiday conversion experience — as in peace and joy simultaneously coursing through your veins like some bubbling, burbling Christmas ornament.

And as if you needed a warning, “Forever Christmas Eve” is mounted — year-round — above the front door. By early November, every room in this 1905-built, historic home shimmers and glimmers with a Christmas spirit passed on to the Hayeses by both of their families.

“At Christmas time it’s very festive,” Katrina says. “It’s a happy house!”

Katrina’s mother, Mickey Guilford, planted the seed in her. “My mom’s favorite holiday is Christmas,” she says. “My birthday’s in December and hers is in November, so we combine it all!” Her mom — who owns 121 collectible Santa Clauses — has four trees. Katrina decorates seven. “Eight, if you count the tiny one in the bathroom,” she adds.

Nat brought his own collection of Christmas trees when they got married in 2017, along with several boxes of ornaments his mother passed on to him. “We’re surrounded by family,” Katrina says happily. And by Christmases past and present.

The preparations, which take a week to complete, began last year on November 1. “Nat brings the boxes in from storage,” says Katrina, “and I always make sure I have everything up and Christmas-ized by Thanksgiving.” That’s when family members exchange ornaments. Long before Christmas morning when they open gifts, Katrina and Nat will have dined each day for two months using Christmas cocktail glasses and two sets of Christmas china — one formal and one everyday. “It’s a joyful time,” Katrina sighs.

But it’s not all about them: “We had 60-plus people at our ‘Christmas on Tate’ event in 2019,” says Katrina. The couple asks guests to contribute food for the Spartan pantry, which assists families in the area. “There’s a lot of hunger and homelessness,” she says. This year, given the constraints of a pandemic, their gathering will be smaller, outside and mask-required.

The couple purchased the Tate Street charmer in July of 2016. Though it had been restored, “The people who owned it didn’t do much,” says Katrina.

Still, she says, “When we were looking at the house from outside, I turned to my husband and said, ‘I love this house.’” Nat countered, “You have to see it all before you fall in love.” But when she stepped inside, Katrina said she had to have it. “My husband said, ‘You don’t even know!’ But I did.”

The couple had searched for a year, touring historic homes. They wanted to be near downtown. They wanted character. They wanted soul, Katrina says.

The house had original floors upstairs and new flooring downstairs, a wide front porch and even a back porch. Original fireplaces and modern conveniences, including a renovated kitchen, were certainly a plus. And the master bedroom had a stained-glass eyebrow window featuring a yellow rose, illuminated with a pull-down light. That window slayed Katrina.

“Everything we looked at that was historic had short ceilings (due to attics converted into second floors) and no central air conditioning. Just window units,” she laments. The sellers were retired and ready to move on. One day Katrina got a call: “The sellers said new price! After many houses, I thought, I was done,” Katrina adds.

Fittingly, for a Christmas house, the house had its own sort of rebirth. According to Mike Cowhig, a city planner who works with historic neighborhoods and oversees the Historic Preservation Commission, the bungalow was brought back from the brink. “It was one of the houses the city bought in the 1980s as part of the redevelopment program and was restored then,” Cowhig says. At the time, College Hill became Greensboro’s first historic district. “It was supposedly featured in Better Homes and Gardens back in the day.” It checked all the boxes, Katrina says.

On Christmas morning, four stockings get filled and hung with care by every fireplace, for family and pets alike, including their two dogs, Bo and Perki.

Katrina, who with her mom’s help bedecked her State Street skin care salon with diaphanous bows, also collects shoes, jewelry and all things leopard. (There will be a touch of leopard on her Christmas stockings this year.)

The couple’s favorite room is the “bar room” where they enjoy cocktails. They creatively reuse brightly colored Crown Royal felt bags as gift bags beneath the bar room tree. Many of them came from Katrina’s late father, Gil Guilford, who collected them over a lifetime. A portrait of Nat’s grandfather, who became chairman and president of Carolina Steel, presides over the room’s corner fireplace. “He’s Nathanael Hayes Sr.,” says Katrina. “Nat (his namesake) is the third.”

Nat, a certified professional accountant, has a Carolina sports-theme tree in a second-floor study Katrina calls a “man cave.” There he displays a beer can collection begun when he was a kid. “He would pick them up while mowing yards.” Nat fashioned shelving from barn wood retrieved from his family’s farm in Summerfield.

The Hayes’ most treasured tree, though, is in the main room. “The big tree has all our ‘memories’ on it — and I love the leopard touches.” While the rule used to be no lights turned on till after Thanksgiving, Katrina has decided to challenge that in 2020.

We could use a bit of extra light and cheer, she decided.

In her book, Joyful, designer and blogger Ingrid Fetell Lee wrote that there is “a quiet hope that the world contains a bit of magic.”

Surely that applies to Tate Street.

And with more than a little hope, the lights will go on early. OH

Cynthia Adams is a contributing editor of O.Henry with an embarrassing number of Christmas trees.

The Creators of NC

Art in Service

Rosalia Torres-Weiner’s flowers blossom

By Wiley Cash

Photographs by Mallory Cash

People begin arriving at 2 p.m. sharp on a Saturday afternoon at the Compare Foods Supermarket on Sharon Amity in east Charlotte: elderly men and women, families with small children, single mothers with babies on their hips — each of them carrying a distinctly different painting of bold, colorful flowers on 8×10 canvases. A few people appear uncertain, others seem excited to discover the source of the mystery that has brought them together. A message on the back of each painting has instructed them to arrive at this location on this day and at this time.

Over the past several days, the paintings — a hundred of them, in fact — have been found scattered around the Queen City on park benches, at bus stops, and inside laundromats, places that one does not expect to find works of art, especially art of this caliber. The artist, Charlotte’s Rosalia Torres-Weiner, is waiting for them, sitting on a folding chair outside her boldly painted art truck. The art truck is a repurposed delivery truck that, before the pandemic, Torres-Weiner used to deliver art supplies and arts education to Charlotte’s underserved Latinx communities. Today, those communities are coming to her.

Some people arrive speaking Spanish, others English, but Torres-Weiner, who was born and raised in Mexico City, moves effortlessly between the two languages, greeting everyone with a warm smile that cannot be denied, even by the mask she wears due to the continued rise in coronavirus cases in North Carolina, where Charlotte’s Latinx population has been particularly affected.

Over the summer, Charlotte’s WBTV reported that Hispanic people make up about 10 percent of North Carolina’s population, but they comprised roughly 46 percent of the state’s coronavirus cases. According to Atrium Health, 25 percent of Hispanics who were tested were positive for COVID-19, while testing for other groups returned positive rates at only 9.5 percent. Torres-Weiner, a self-described “artivist” whose work is fueled by service to her community, felt called to respond to the devastating effects of the COVID crisis.

“All my work comes from the community, and while I obeyed the orders to stay home, I realized that I needed to do something,” she says. She soon found herself asking: “What can I do to produce art and help the Latino community?”

This question led to an idea, and the idea eventually grew into action. Torres-Weiner’s husband, Ben Weiner, who works in technology, has grown accustomed to his wife coming up with these kinds of ideas, ideas that put her art to work in service of the community. He lovingly refers to these moments of inspiration, which he envisions as tiny black beans that grow into something larger, as frijolitos, and he has dubbed his wife’s visionary projects as “Frijolito, Inc.” As usual — and as her husband probably predicted — Torres-Weiner’s ideas on how to confront COVID grew.

One day, while bouncing ideas off a friend who is also part of Charlotte’s Latinx community, Torres-Weiner decided that she would find a way to distribute sanitization supplies to underserved communities. Her friend told her that was a great idea, but what people really needed was food. Mother and fathers were dying of COVID, leaving behind spouses and children who needed support. Yes, they needed supplies to protect their bodies, but they also needed food, especially children, who were going to bed hungry, their physical pain compounded by the emotional pain of losing a parent to the coronavirus.

Pain and beauty: Torres-Weiner was motivated by one and desperate to spread the other, and she recalled a quote from the impressionist painter Claude Monet, “I must have flowers, always, and always.” She knew how to spread beauty, and she decided to paint a hundred 8×10 canvases with bold, colorful flowers. But she knew she needed help finding a way to address the pain people were feeling. Frijolito, Inc. sprang into action.

Although she has made a living as a professional artist, Torres-Weiner went to college for business administration. “My sister became a lawyer, my other sister became a doctor, so when I told my mother I wanted to be an artist, there was not a choice,” she says. But sometimes mothers know best, and Torres-Weiner admits that her business background has provided the tools she needed to find funding and partnerships for her art projects. For her latest, she reached out to Google Fiber. With their support, Torres-Weiner was able to ensure that for each painting she painted, its new owner would have access to a gift bag containing hand sanitizer, masks, soap and other items. Also, each bag would contain a $50 gift card to Compare Foods Supermarket.

As is often the case when Torres-Weiner executes a plan, her husband is on-site today. Each time someone arrives with their newfound art in hand, Torres-Weiner checks the number on the back of the painting and calls it out to her husband, who is inside the art truck, where the gifts bags are waiting. Out of the 100 paintings Torres-Weiner distributed across Charlotte, 89 find their way back to their creator, and although the new owners get to keep the paintings, many of them cannot believe their good fortune. Surely there is a catch, some of them ask. Others try to return their paintings, certain that such beautiful art cannot have been passed on to them for free.

If you ask Torres-Weiner why she feels compelled to use her art to support her community, she will respond by telling you that this is a community that has always supported her from the moment she and her husband arrived in Charlotte from Los Angeles in the mid-1990s. “I remember when we moved here,” she says, “and we saw a church on almost every corner of the city, and we saw everyone playing baseball and taking their kids to activities, and my husband and I looked at each other and said, ‘This is our city. This place is going to embrace us.’ And it did. We’ve been here 26 years.”

But others in the city were not as convinced as Torres-Weiner that Charlotte was the place for her and her art. “When I started painting my colorful art, someone said, ‘You need to move to Santa Fe or San Francisco.’ I’m glad I didn’t listen.” Another time, while she was working on a mural in Washington, D.C., she told someone that she was ready to return home. They asked if she was heading back to Mexico. “No,” she said. “I’m going back to Charlotte, North Carolina. That’s my home.”

But home changes, and artists adapt, and Torres-Weiner has adapted, easily blending her Mexican cultural heritage into her work as a Mexican-American artivist living in Charlotte. By way of example, she references cuisine and how foodways can merge cultures and bring people together.

A few years ago, while standing in line at a walk-up Mexican restaurant that had long been a secret kept within the Latinx community, Torres-Weiner noticed the diversity of people waiting with her, and she struck up a conversation with a Black man who was standing behind her. He saw the paint on her clothes, and he asked if she was a painter. She said she was. As a matter of fact, she had painted the nearby mural of the Lady of Guadalupe on Central Avenue. The man told her the neighborhood had once housed primarily Black families, and before that White Charlotteans had made it their home. Now, the neighborhood was home primarily to members of the Latinx community, and Torres-Weiner explained that she was painting the mural to welcome them to Charlotte. While they waited for their lunch, Torres-Weiner and the man continued to talk about old landmarks, how communities change, how they maintain their hospitality, how they can welcome anyone who is looking for a home.

Rosalia Torres-Weiner’s career has taken her all over the world, and her work has been featured in major museum collections and ended up on the cover of a United States history textbook. But no matter where she goes or where her work is showcased, Charlotte remains home. “Last year, I was selected to represent North Carolina as a Mexican artist when an event was organized in Mexico City that invited one artist from each state in America to represent the arts,” she says. “And when they chose me as North Carolina’s artist, I was so proud.”

The day’s event has ended. The confused and curious people who arrived with a gorgeous painting in one hand are leaving with a bag full of groceries and COVID supplies in the other.

No one is more pleased than Torres-Weiner. It is obvious that her day of service has regenerated her, guaranteeing that she will soon find another way to put her art into action to serve her community. What else can an artivist do but create and serve? “It’s my food, it’s my air,” she says. “It is my Christmas.” OH

Wiley Cash and his photographer wife, Mallory, live in Wilmington, N.C. His latest novel, The Last Ballad, is available wherever books are sold.

The Elf Doctor

Dr. Kimberlee D. Shaw prescribes a little

comic relief to cure the pandemic blues

By Cynthia Adams • Photographs by Bert VanderVeen

With a languorous stretch and neck roll, Dr. Kimberlee Shaw notes the time. It is 5:30 p.m. at Eagle Family Medicine at Village, a practice located on East Wendover Avenue.

Pandemic workdays unspool in spectacularly stressful ways. Chronic stress, as the doctor knows so well, causes fatigue, grumpiness, ennui and a host of physical issues. Shaw has always prescribed a liberal application of humor to ease life’s pain.

But 2020 has gnawed gaiety down to the bone.

As Shaw stands up, the soft jangling of jingle bells remind her that she does have a remedy for grumpiness and ennui, by golly. Squaring athletic shoulders (Shaw is a former UNC-Ch rowing team member), she shakes off fatigue, which creates a serious glitter storm.

Er, what?

That’s right. Glitter emanates from Shaw herself, and a hair band with a felt Christmas tree bobbles atop her mop of irrepressible light brown curls.

This is no staid doctor in a lab coat. No siree. Shaw has donned a lurid Christmas sweater paired with bedazzled Lurex emerald pants.

And the matching green shoes?

Elf shoes, straight from a Keebler ad.

Shaw doubles down on her dose of glee by putting on shades embellished with reindeer horns, her candy cane hoop earrings dangling wildly.

Her cure for 2020’s malaise has been patient-tested; the known side effects are giggling and irrepressible mirth. And the application of her novel armamentarium vanquishes tension and pain in statistically significant ways.

From a room down the hall, she retrieves a bin containing some of her after-Christmas haul — the “schlocky stuff” marked at 70 percent off — leaving a glittering debris field in her wake, sequins and shimmering, colorful bits sparkling in the industrial fluorescent light.

It’s the annual reappearance of dress-up-like-elves time at the physicians’ offices, in preparation for the holiday season. Shaw has worked here for a decade.

A few of Shaw’s staff groan. One moans from her office down the hall, “I forgot!”

Amy, a petite 20-year veteran of nursing, plays the office curmudgeon: “I don’t want to dress up!”

Shaw doesn’t argue or coax. She simply begins a jig in the hallway, heels kicking. Resistance is futile.

“Just be human; just make people laugh,” Shaw advises. “I’m doing this because it makes me happy.”

“I love Christmas, I just don’t want to dress up,” says Amy. “But I love Dr. Shaw and would do anything for her.”

Within minutes, Amy emerges from an office, transformed into a grumpy elf, now galumphing in oversized shoes and kicking up her own bedazzled heels.

Before long, Dr. Dean Mitchell sticks his head out into the hallway. “Hey, what is all the fun about?”

He immediately joins in the hijinks, pretending to be a patient playfully checking out. Mugging for a camera, Mitchell offers Dum Dum lollipops in payment.

Privately, Mitchell correctly diagnoses what was happening: A contagion of laughter. Patient zero for this contagion was Shaw, who was happier than anyone, cavorting, twirling. Effervescent.

Patient reactions when a costumed Shaw springs into an examining room as they wait in a hospital gown?

“People start hee-hawing,” Shaw says.

Yet Shaw does take medicine seriously, and recalls having one or two instances when a patient was in “for something serious.”

She navigates those instances with care. Once, dressed as Cat in the Hat for Halloween — wearing giant white hands and that crazy hat — she realized she had difficult news to convey.

“We were having a good time, but then we had to have this big conversation,” recalls Shaw. “I realized I was sitting there with this big hat on and I wanted them to know I took it seriously.”

She removed the comical hat and did away with the costume.

“I said, ‘Excuse me. Let me take this off.’ I don’t want people leaving thinking I don’t take them seriously.”

“You’d be surprised how much people don’t complain [when I’m in costume]. I don’t know if they forget themselves?”

Yet Shaw, the perennial optimist, has more than a passing acquaintance with sorrow. One sorrow was pivotal.

There were no other physicians in her family, but since babyhood Shaw wanted to be a doctor. Her parents, Jerry and Carolyn Dilda, fully supported her.

Her father pushed Shaw to apply for the N.C. Board of Governor’s scholarship. It was merit-based but there was a financial component for applicants; she worried he would procrastinate on the paperwork.

“I told him he had to get his taxes done. ‘Write the essay,’ he told me. ‘I’ll get the taxes done.’ And he did.”

Shaw was working in Boston when she was called home; her father was at the hospital following a catastrophic stroke. She reached the Charlotte hospital by evening.

“They kept him alive long enough for us to all get there.”

She added, “Daddy didn’t believe in doctors — unless you are bleeding and cannot stop the bleeding. He had keeled over at his desk, age 57, at home.”

The very next day, Shaw received the letter announcing her full ride to medical school.

“He died in May. I began medical school in August. The experience of being on that side as a patient, that life-changing event, made me approach medical school in a completely different way,” she explains.

Losing her father as her own life’s dreams were opening might have derailed her. But instead, her first year of medical school, amidst gutting loss, lent a fierce focus for the young physician.

“It was a blessing. It gave me something to do . . . to focus on something other than that grief.”

It also “opened a hole in me,” Shaw says, “so the joy could come in.”

She learned her father, an engineer with a small business, had uncontrolled sleep apnea. He was taking aspirin all the time. He had uncontrolled high blood pressure. She would apply these insights later.

But Shaw was riveted by the memory of an awkward young physician who met with her family on the night of her father’s death.

“He might have been a first-year resident.” She noted how he “was clearly out of his element.”

Adding to the direness of the situation was the resident’s discomfort and the sterility of the setting.

“Every part of it was not good. And you can make that better,” she has discovered. “But at the funeral home, the director was so great. He reassured us. I almost, at that point, thought, ‘Maybe I should be a funeral director.’”

Shaw was struck by the experience of seeing death met with such grace and understanding, profoundly different than the resident had handled it.

She retained the lesson.

This became the central theme she returns to: Sorrow makes way for happiness. Wounds heal.

There was a telling coincidence while she was at Carolina studying medicine. The Robin Williams film, Patch Adams, was being filmed on the campus. Shaw watched Williams wheeling his bike “down Franklin Street, in character.”

In costume.

It planted a seed.

Dr. Patch Adams, on whom the film is based, championed the idea of laughter therapy, and founded the much-loved Gesundheit! Institute.

“There is a reason for the phrase comic relief,” wrote Adams in his book, House Calls. “When suffering is great, there is a call for relief. Whatever we are nervous about or emotional over is where jokes come from.”

He cited Voltaire: “The purpose of the doctor is to entertain the patient while disease takes its course.”

Shaw’s parents, her biggest influences, were original thinkers, too. Her mother enjoyed historic reenactments, returning to school to learn historically accurate cooking. She raised chickens “and can grow anything.”

Whereas Shaw’s mother “was from a prim and proper Southern background, Daddy was the force.”

She learned joy by virtue of her parents’ example: “Christmas is not what you get. It’s what you give; the joy of the holidays.”

Their Christmases were simple: “My mother chose, intentionally, to keep it simple and I see that this led to thinking buying gifts was not all it’s cracked up to be.”

“My kids adore her,” Shaw says. “My mother showed up four years ago wearing a witch hat and these witch shoes for her regular annual wellness exam with Dr. Elaine Griffin! Stone faced normal! Just checked in. Sat down. She just likes to do that one little thing that is different.”

And so does her daughter:

“Just do something — be human! Just make people laugh. There’s no reason not to! I do this because it makes me happy,” she says.

Patch Adams once said, “the reason adults should look as though they are having fun is to give kids a reason to want to grow up.”

There remain ways we can alleviate the pain of a pandemic.

“Many, little things we can do,” Shaw insists.

“Now I’m looking for funny masks,” she says, her eyes twinkling. “Why not? Why not make it funny?” OH

Cynthia Adams is a contributing editor of O.Henry whose dog is named for Dr. Patch Adams, whom she once met. If she’s not Dr. Shaw’s favorite patient, please don’t tell her.

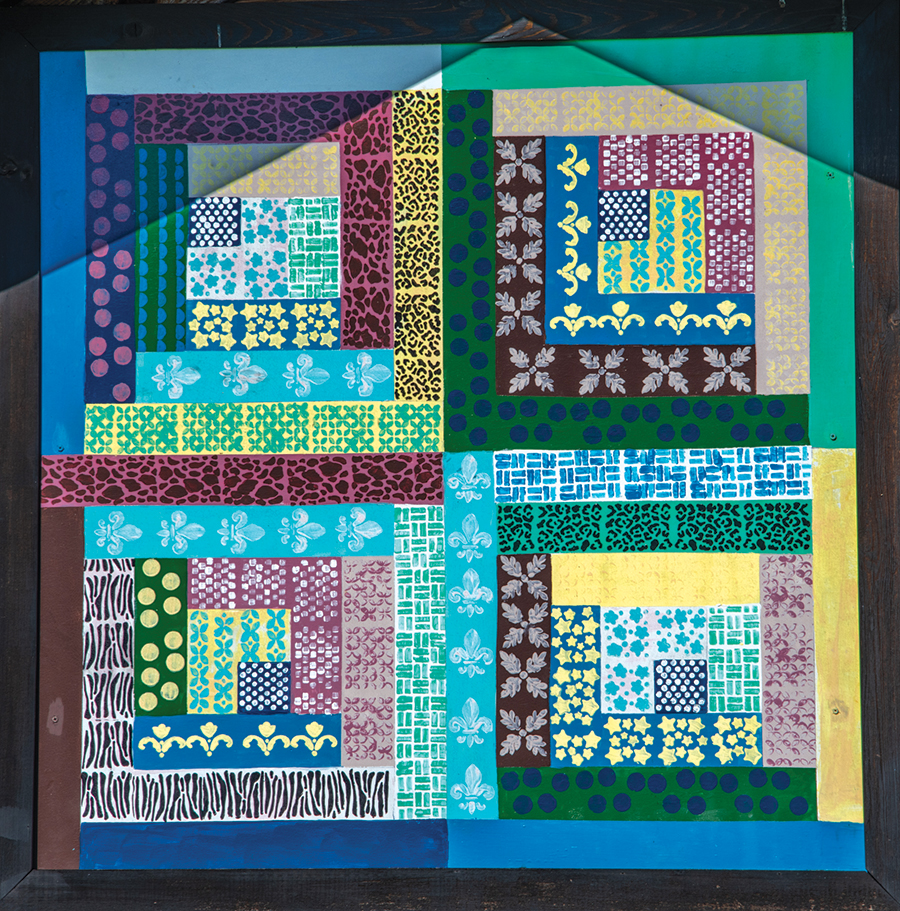

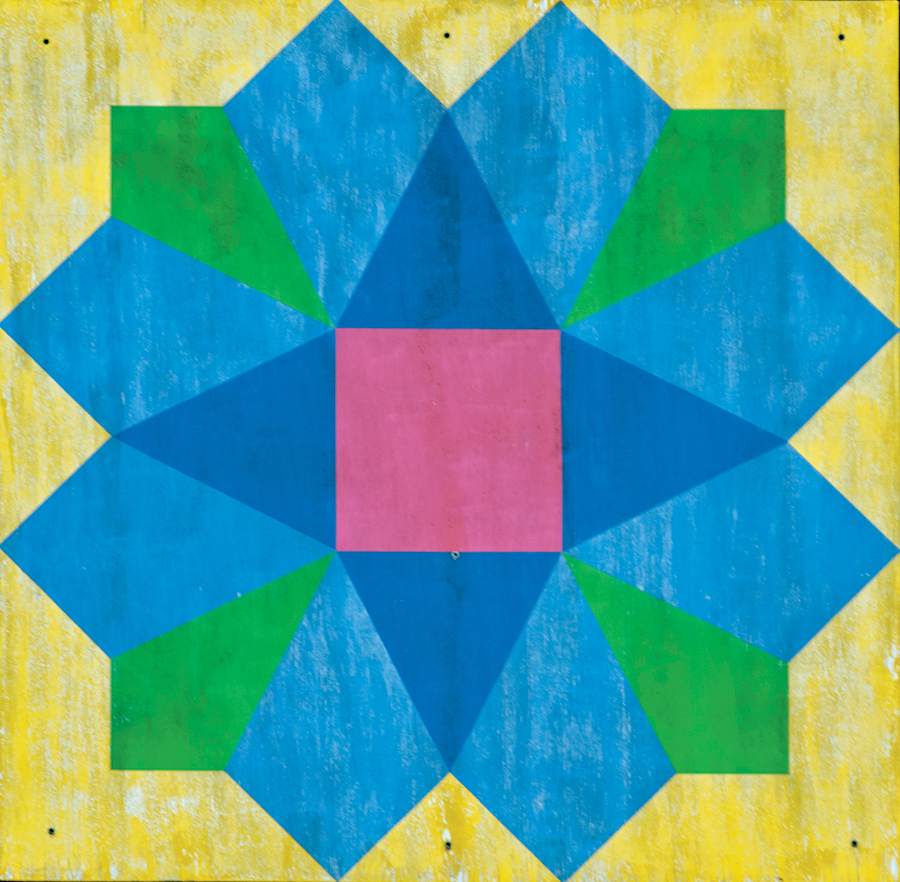

All Squared Away

Barn quilts that blanket the landscape

By Maria Johnson • Photographs By Lynn Donovan

We know you’re tired of scandals and lies, but we think you deserve to know the truth about barn quilts.

They’re not quilts, at least not the kind you cuddle under.

And only a fraction of them hang on barns.

There. We said it. Cover-up exposed.

Still, we know this won’t stop folks from posting the large kaleidoscopic squares on the sides of barns — or from hanging shrunken versions in decidedly un-Old-MacDonald locations: bedrooms, sunrooms, sheds, patios and storefronts.

Beth Ball, the owner of BBs Barn Quilts in Alamance County, displays a 2-by-2-foot barn quilt on the white vinyl fence outside her Haw River townhouse. She flips one side of the reversible panel, a red-white-and-blue design, toward her patio on patriotic holidays. The other side, a vibrant starburst, shines the rest of the year.

“It’s a different way to bring some art into your outdoor space,” she says.

In the last two years, Ball, who leads barn quilt classes as fundraisers for nonprofit groups, has walked 600 to 700 people through the process of drawing their designs on primed plywood then painting them with exterior latex paint. Students can choose from the 25 geometric patterns that Ball offers, or they can use their own patterns. Many people bring designs from family quilts.

“They’re very sentimental to people. They’ll say, ‘Oh, this one belonged to my mom,’” she says.

At the Wallburg Emporium & Coffee Shop near Winston-Salem, barista Sheila Craven leads a couple of barn quilt classes every month. Participants leave with a 2-by-2-foot square in the “Yankee Puzzle” pattern, done in the colors of their choosing. The whole process takes about three hours, which gives students plenty of time to sip coffee while they literally watch paint dry.

The history of barn quilts in this country goes back to Dutch and German settlers of the 1600s, who decorated their barns with “hex signs” to invite good luck and ward off evil spirits. The designs repeated decorative motifs found inside their homes: flowers, birds, hearts, trees and stars.

Later, some barn signs, especially those on Quaker farms, borrowed from cloth quilts that were draped outside homes on the Underground Railroad, a conduit for escaped slaves. Patterns in squares conveyed coded information: bear claws meant take a mountainous route; a bowtie pattern meant to wear a disguise; a log cabin design of layered rectangles at right angles meant to seek shelter — or that the owner of the home was safe to talk to.

Hex signs fell out of favor with the rise of Christian churches in rural areas. The craft lolled around for decades until it resurfaced in the early 2000s, thanks to an Ohio woman who popularized barn quilts as a tribute to her mother, a quilter of the needle-and-thread variety.

In the Piedmont, Rockingham County and Randolph County maintain quilt trails for self-guided driving tours. Slightly farther afield, mountainous Ashe County boasts a trail with a whopping 150 sites.

Professional artists often paint the big squares that show up on trails, but when it comes to the take-home panels, this folk art belongs squarely to the folks.

“In many cases, they’re the only thing the student has ever painted,” says Ball. OH

For information about a December 12 quilt-painting class lead by Beth Ball to benefit Alamance Arts, go to alamancearts.org/community-classes. Check the Facebook page of Wallburg Emporium & Coffee Shop for their next class. Find the Rockingham County quilt trail at visitrockinghamcountync.com/quilt-trail/. The Randolph County quilt trail: randolphcountync.gov/Departments/Soil-and-Water/Quilt-Trail or www.piedmontconservation.org/projects/quilttrail/. The Ashe County trail: ashecountyarts.org/barn-quilts.php. Individual listings are subject to change, so wrap yourself in a sense of adventure and flexibility if you hit the road.

Ann Beane makes fabric quilts, but the idea for her barn quilt came from another source: a desk calendar with pictures of quilt squares. “Four Dancing Tulips” leapt out at her. “I just love flowers. I work outside all the time, and I just wanted something that looked different,” she says. The square, painted by the Randolph County Quilters Guild for the local quilt trail, hangs on a reconstructed log cabin owned by Ann and her husband, Lyndon. The perky design regularly stops traffic at 5171 Fred Lineberry Road, Randleman. “Especially in the spring time and now, when the leaves are turning, they’ll be pulled over, and I’ll think, ‘Oh, do they have car trouble?’ But then I’ll see their cameras,” Ann says.

Talk about a family affair. Mona Farmer’s paternal grandmother, Anna D. Bean, was an avid quilter, and she left behind several unfinished quilt tops. Mona loved the one with the log cabin design, so when she heard about the Rockingham County Quilt Trail, Mona asked her granddaughter, Brianna Hennis, to paint a square based on it. Brianna’s interpretation hangs on the log cabin where Mona and her husband, Stanley, live, a refurbished tobacco pack house that dates back more than 100 years. You can find the cabin at Pin Oak Farm, 215 McDaniel Road in Eden.

Come winter, Ava Rakestraw, who adored being outside in warmer weather, occupied herself with making quilts. When it came time to stitch the squares together, she unfurled her work on a makeshift quilting frame — long boards laid over the backs of chairs. Before she died at age 102, Ava gave quilts to five great-grandchildren, including Ann Rakestraw Dixon’s sons, Kevin and Keith; the double wedding ring pattern on those quilts inspired the barn quilt that adorns an old tobacco barn on Ann’s property at 291 Crowder Road, Madison. Rockingham County artist Patricia Perdue painted the panel.

Who says barn quilts have to be painted on wood panels? Artist Teresa Talley Phillips shattered that notion when she made a glass mosaic for the Chinqua-Penn Walking Trail, a 1.7-mile loop named for the former home of Jeff and Betsy Penn, Reidsville’s Gilded Age power couple. The state now owns much of the estate, site of the N.C. Upper Piedmont Research Station, an agricultural testing ground. The 2-by-2-foot square — made with backer board, stained glass and grout — depicts the cattle, birds, bamboo and butterflies seen along the popular trail. The center of the square shows the Summer House, a gazebo-like structure furnished with mill-stone tables and benches beside Betsy Lake. The trailhead and parking lot are near 2138 Wentworth Street, Reidsville.

About 20 years ago — before the Randolph County Barn Quilt Trail existed — Joann Hammer saw a story about a lady who made the large squares in a nearby community. A glowing design called Nirvana caught Joann’s attention. “If I had a barn, I would want one,” she says. Alas, Joann didn’t have a barn, so she did the next best thing: she paid for the artist to create another Nirvana as a gift for her daughter, Wanda Cox, and her husband, Dannie, who had a barn on their property. Today, the panel still hangs on the Coxes’ barn beside the road at 4804 Moffitt Mill Road, Ramseur.

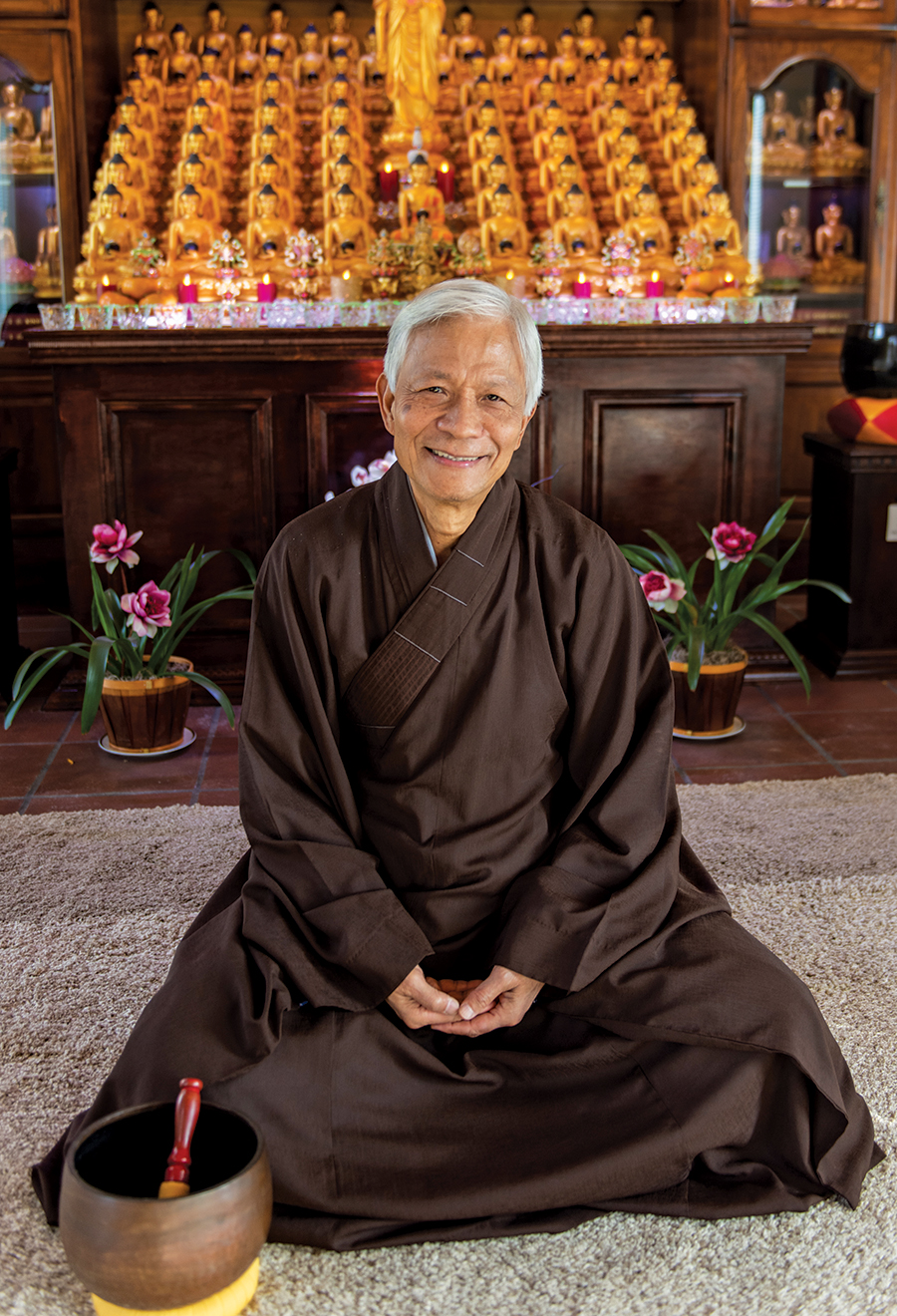

Prayers of the People

Photographs by Lynn Donovan

Not every prayer is formal or religious. Many are not. Bestselling author Anne Lamott wrote Help, Thanks, Wow as a reminder that, yep, a prayer can be as simple as one word.

When it comes to asking for guidance, there isn’t a formula. We can show gratitude in as many ways as there are moments in the day. And there’s no wrong way.

We can pray together.

We can pray alone.

It doesn’t even have to be out loud.

Dance might be our prayer.

Or song.

Or our gentle steps upon this Earth.

“I see you,” is a prayer of recognition.

“I love you” is better.

Sometimes our thoughtful actions are another’s answered prayer.

What is prayer but faith that we are a part of something bigger than ourselves?

We asked a handful of religious and spiritual leaders across Greensboro to offer their prayers for our community and the world at large as a way of calling in a bit of hope at the end of this emotionally turbulent year.

We add our prayers to theirs. We figured we could use as many as we could get.

A Prayer for Oneness

By Son Pham

All living beings are my parents

All living beings are my siblings

All living beings are suffering

I fervently generate indestructible love and compassion

By the blessing of immeasurable love

By the force of awareness of unmistaken truth

Of all previous great holy beings

May all living beings be free from the dangers of illness

Grasping hands in a circle of friendship

Seeing the wisdom of benefit to self and others

By the perfections of generosity, morality and patience

May all living beings be free from the dangers of illness

This disease, as well as all future wars, famine, and crises

Shall not arise to be named

From the smallest plant to every creature on this planet

May all be victorious over unwanted harm.

**This prayer, an essence of a prayer composed by Buddhist monk Demo Rinpoche, is offered daily at the Thousand Buddha Temple.

Before prayer, a breathing meditation is practiced to clear the mind of distracting thoughts. And for the prayer to be effective, says Son Pham, we must make a strong connection to the people we are praying for. Imagine all living beings are your parents, in this lifetime and our uncountable past lives. Then awaken your mind by focusing on what is happening around you, and who and what you are praying for. Understanding the sufferings of all people on this planet makes it possible to generate pure love and compassion for everyone, not just the people we like or love.

Son Pham is the principal teacher and founder of Thousand Buddha Temple in Greensboro. A lifelong Buddhist, Pham offers private consultations for professionals seeking stress management through meditation and Buddhist principles. www.chuanganphat.org

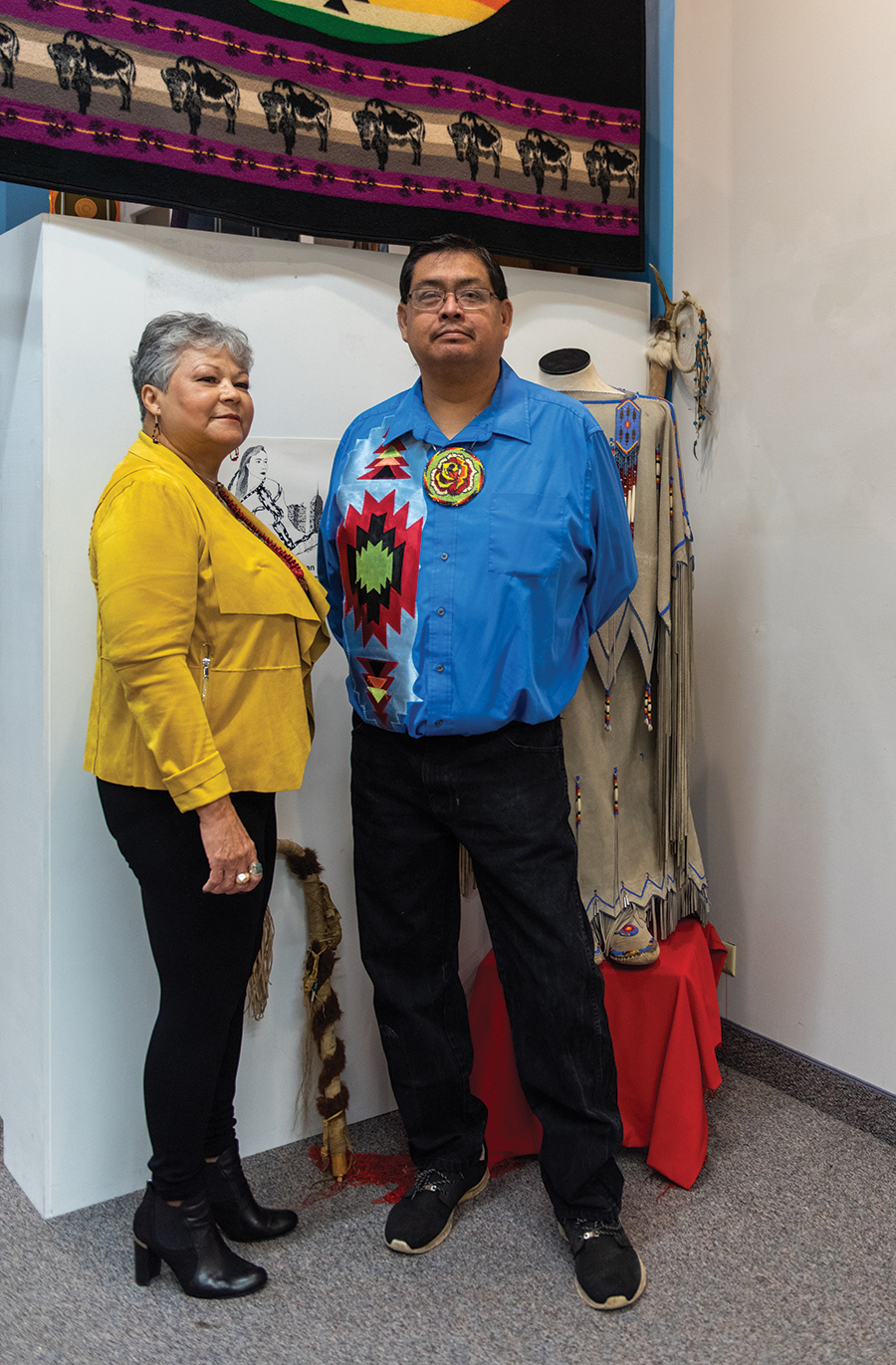

A Native

American Blessing

By Daphine Locklear Yellowbird Strickland & Ray Silva

Creator,

We come to You in reverence and with grateful hearts.

We ask for Your blessings upon our community and communities throughout Mother Earth.

We are in a time of trouble.

Disease has spread throughout our land and is bringing sickness and death to our families, our friends and our neighbors.

We have failed to care for Mother Earth and now she is raging with fires, storms and a pandemic throughout all nations. She is weeping for our grandmothers, our children, our sisters and brothers.

Help us to cease from polluting and poisoning her and to work as one to restore her harmony.

There is much bitterness and divisiveness within our communities.

Teach us to not listen to the two-hearted, the destroyers of minds, the haters and self-made leaders — those who lust for wealth and power and lead us into confusion and darkness.

Remind us to seek out visions of world beauty and nonviolence within our community and throughout Mother Earth.

Remind us all of our roots, our heritages and the wisdom bestowed upon us by our ancestors, for they will never misguide or mislead us.

We ask that You bless and keep us safe and healthy, full of joy and good will toward all living beings.

Lead us to be: Visionaries, for “where there is no vision, there is no hope”; Trailblazers, for “if not us, who?”; Wisdom keepers to preserve and keep our many histories, cultures and traditions alive; Leaders to give direction to those who follow; and faith to reach the possible when it seems impossible.

For these things we offer our gratitude and praise to You.

Aho (Amen)

**This prayer includes words of wisdom from the late Ruth L. Revels, who was an enrolled member of the Lumbee tribe.

Daphine Locklear Yellowbird Strickland is an enrolled member of the Lumbee tribe and is part Tuscarora. Ray Silva is an enrolled member of the Laguna Pueblo tribe. They co-created this blessing on behalf of the Guilford County Native American Association. www.facebook.com/guilfordnativepowwow2020

Calling My Heart

By Linda Beatrice Brown

I

Prayer in Winter

There is some mystery calling my heart,

Some angel dust, some lustrous wings.

Oh Holy One, oh beautiful and fierce lover of souls,

Mother, I need Your incandescent voice.

I need Your blanket of moonlight, Your star that never leaves us, never weakens.

The road is full of pits and shadows. I stumble often.

Light up my path or I am lost.

Oh Mother, do You know how the darkness threatens and cajoles us?

We have removed ourselves from ourselves.

No wonder we cry. No wonder we kill.

Mother, I need Your bird song, Your voice,

Your waterfall of love,

Your gold bright music.

Come to my heart that is Yours always.

I hold out my hand.

Please take it.

II

Answer

Listen, the ocean waves are breathing in you,

Waves caroling my name.

I am the heartbeat of the planet.

When you call I am the breeze on your neck.

Listen, fasten your sandals and take my hand.

We go to drink the source of life, the eternal Spring.

Understand, your heart will be made whole.

Do not be deceived.

I live within the darkness.

I am waiting to visit my blinding radiance upon you.

All things in their time.

Do not despair, but know me.

Those who know me know the heart of love.

I hold out my hand.

Please take it.

(This is the winter version of “A Prayer for Human Healing in Our Time,” also by Linda Beatrice Brown)

Linda Beatrice Brown has written a number of novels, poems, plays, short stories and essays. Currently on the faculty at The School at Space for Conscious Living, she’s been a member of Holy Trinity Episcopal Church for over 25 years.

www.lindabeatricebrownauthor.com

A Prayer for Hope

By Greg Farrand

Gracious God, Infinite Mystery, Divine Source,

As we step tentatively and inevitably into the unknown of this New Year, we are in desperate need of hope. The atmosphere, the very air we breathe, is charged with fear, anger, mistrust and cynicism.

Without intervention, without intention, the gravitational pull of these dark impulses drag us into a swirling state of anxiety and reactivity.

We begin to believe that real change is impossible.

We metabolize the delusion that we are separate and on our own, like cosmic orphans in a hostile universe.

It looks like darkness will win and, Beloved One, we are in

need of hope.

Not the sugary hope that plugs its ears and shuts its eyes. We need the gritty, raw, dirt-under-the-fingernails kind of hope that lifts our chins and rekindles our inner fire.

Give us a spacious hope that reminds us, again and again, that love and light always wins. Always.

Give us an active hope that reveals the power of our small acts of kindness and compassion — small acts that ripple out like waves that touch countless lives. These small acts flow together to

heal the world.

Give us a connected hope that heals the delusion that we are alone and isolated.

An abundant hope that knows resources are not scarce. There is enough food to feed everyone. Enough clothes to cover everyone. Enough homes to house everyone. We don’t need more resources, O God, we need Your hope to stir creative compassion.

And with this hope, we brush away the dust of cynicism and constricted living and step into this new, unknown year with anticipation and gratitude for all that will evolve and unfold.

Amen.

Rev. Greg Farrand is the co-director of Second Breath Center, a center that offers life transforming spiritual practices rooted in the Christian wisdom tradition. www.secondbreathcenter.com.

A New Year’s Blessing

By Kim Priddy

Help us to begin this year

with grace,

and to remember

the courage

that carried us here.

Ready our hearts

to engage the world,

for there are dreams

to be realized.

Prepare our souls

for exciting possibilities,

for there are new terrains

to traverse.

Strengthen our minds

to resist the darkness,

for there is light

to be played in.

And now

we are here,

at the threshold

of what has been

and what is to come.

Hope calls

our heart,

our soul,

our mind,

that we might enter

into a new year

filled with assurance and resolution.

And may it be so . . . Amen.

Rev. Kim Priddy is the pastor of Sedgefield Presbyterian Church in Greensboro. Her ministerial experiences have been shaped through her work with many of the most vulnerable in her

community. sedgefieldpresbyterian.org

A Prayer to the Loving Creator

By Daran Mitchell

Amidst the wild shadows that cover and hover over the evening of our deepest fears, we pause to return to You our humble thanks. With hearts overflowing with joy and an eye single to Your never-failing love, we offer to You our sincere petitions.

Loving Creator, our journeys to this precipice have been marked with much sorrow and grief. The restiveness of this year has taken its toll upon the human circle. We wince as we witness the unraveling of life as we have known and lived it. The strain of toil has caused our spirits to wilt as we gather the shards of what started out to be a promising year. We lay before You our pain and bear before You our deepest anguish. From the harshness and restlessness of life, filled with hectic haste and selfish strife, we come to You to learn good will and to be warmed by Your presence.

Eternal Spirit, we confess afresh that we are not sure what lies beyond the bluffs of this blistering and blazing precipice. Our souls are buffeted with nagging queries not yet answered; with distressing cries that have seemingly gone unheard. We long for the peace that is Yours to give and ours to receive. Grant, we pray, ears and eyes to behold the life that is beyond this summit of uncertainty. Give hope to our anxious strivings and a gentle pace to balance the frantic search for what we have sought to call a new normal. We stand waiting and watching as You speak through the chill of winter and the promise and dawn of yet a new year.

In your Name,

Amen.

Daran H. Mitchell is the senior minister of Trinity African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church in Greensboro. He is an adjunct professor of pastoral theology at Hood Theological Seminary in Salisbury and an adjunct professor of religion at Greensboro College. www.facebook.com/trinityameziongreensboro

A Conversation with God

By Marilyn Wolf

Hello God,

I’ve come to You so many times, asking for guidance, answers or forgiveness.

This time I’m asking for peace. And to be honest, I’m not even sure what that means. But I’m pretty sure what peace is not. Peace isn’t being trouble-free. It’s not having things go my way or getting what I want. Peace is not a goal, an achievement or a prize. It is not something I can make happen no matter how hard I pray or meditate.

These days, I hear lots of pithy sayings about peace. It’s every step you take. It’s the space between the breaths. It’s our true essence. I kind of get all that on one level, but actually, if someone asked me to explain how peace is the space between the breaths, I’d have to make something up and hope I sounded smart.

In church, I’ve heard “the peace of God which surpasses all understanding.” So, I guess it’s OK that I don’t understand it. Maybe peace isn’t something we can get with our minds. Is it possible that it’s really just a state of being? Being OK no matter what’s going on around me, like a boat with a deep rudder that can ride out the storm? But if I have to wait until the storms pass to be at peace, then I could be waiting a long time. And at this stage in my life, I don’t have that kind of time.

Now, here’s a thought: Maybe peace is giving up trying to figure out what peace is, to quit pursuing it, and to stop feeling bad about myself because I’m not as peaceful as I think I ought to be. In other words, being OK no matter what. Being peaceful even when I’m not peaceful? Now, that is definitely a peace that surpasses all understanding.

Thank you, God. I like it. And for now, I think I’m OK.

Marilyn Wolf, M.Ed. is a retired psychotherapist who offers guidance for spiritual and personal growth through her practice. She is also an Enneagram teacher, certified energy work practitioner and founding director of The School at Space for Conscious Living. www.spaceforconsciousliving.com.

A Prayer for All Beings, Everywhere

By Fred Guttman

Our God and God of our ancestors,

God of all human beings and God of all animals and plants,

We ask You to bless all human beings, wherever they may dwell.

May it be God’s will to comfort those who are ill and in distress.

May it be God’s will to deliver them speedily from the darkness to the light.

Bless all Your children, in every land, nation and community.

Unite us all in understanding.

Unite us all in mutual helpfulness.

Unite us all with the spirit of community.

Oh God, hasten the day, please. Bimhayrah veyamanu — soon and speedily.

Hasten the day when we, all of us as Your children, God, can rejoice in a world where our bodies and souls are healed; a world of health and peace!

Amen.

Fred Guttman has been a rabbi since 1979 and lived in Israel for 13 years. He has served as the rabbi of Temple Emanuel in Greensboro since 1995 and plans to retire this summer. www.tegreensboro.org/meet-our-staff

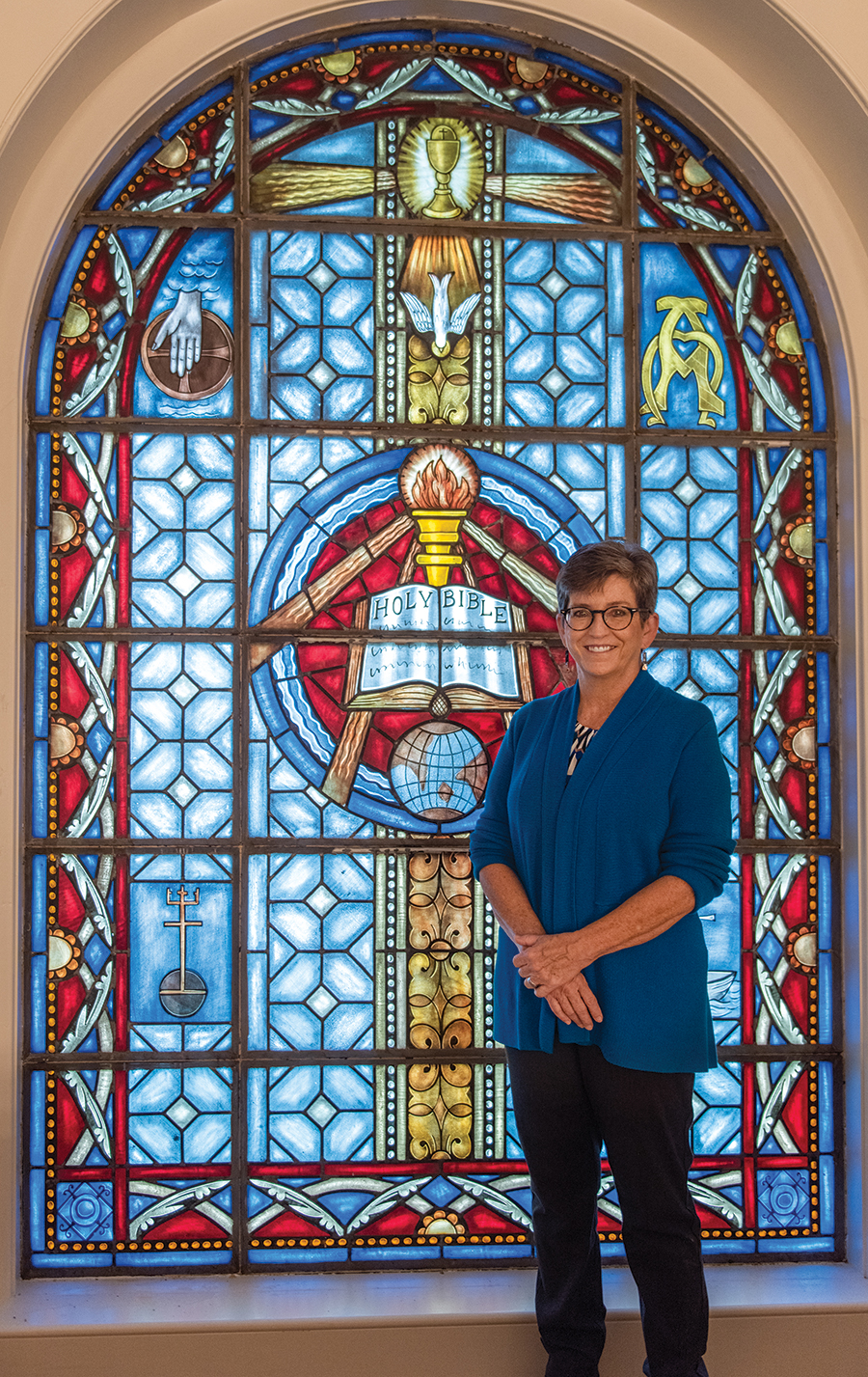

A Prayer for Peace

By Julie Peeples

Holy One,

Can we talk?

This long year, 2020, has just been too much! Too much distancing, too much Zoom, too much loss, too much change and way too much partisan rhetoric and hate speech.

Yet somehow in the midst of it all, there has been no quarantine on Your love, no distance between us and Your grace. We have glimpsed Your presence in the life-giving, unexpected gifts of sidewalk-chalk flowers, fresh-baked cookies dropped off on the porch, smiles detectable even above a mask. We’ve caught the essence of Your love in compassionate medical workers, dedicated teachers and patient parents. We’ve witnessed Your creative beauty in the musicians, artists and poets whose talents have lifted our flagging spirits.

Call to us now — whisper Your peace to us in the chilly winter wind, in the distant sunrise, in the bare beauty of the trees. Infect us with Your peace that passes all understanding. Make peace the new pandemic for which there is no cure. Peace with justice, peace with renewed commitment to the common good. Make this peace-virus so hard to resist that more and more of us will be eager to come down with it and share it with others. Give us courage to be determined advocates for the rights and dignity of all people, so that all may live in peace.

Thank You, Gracious Spirit, for carrying us through this tumultuous year, and assuring us that no matter what 2021 brings, we will see it through together.

Amen.

Julie Peeples has been the senior minister of Congregational United Church of Christ since 1991. She is an advocate for equality and justice issues, particularly for LGBTQ and immigrant rights. congregationalucc.com

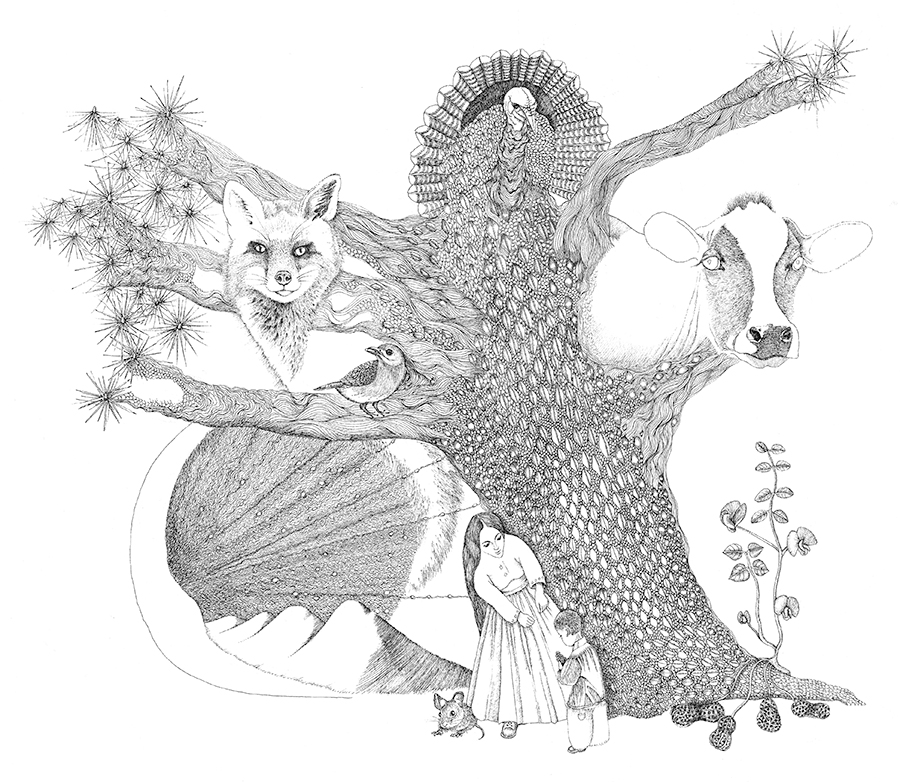

Christmas Stories, Somewhat but Mostly Not True

By Daniel Wallace

Illustration by Ippy Patterson

The oldest family Christmas story I know is about my great grandmother, Nona. This is the century before last. Nona was a widow. As far as anyone could tell, Nona had always been a widow — some said she was born one. The truth is that her husband, my great grandfather, perished much too young in the salt mines of northern Alabama, leaving her alone with a brand-new baby, my grandfather, Ewing. As everyone who knows anything knows, Alabama was once home to the largest salt deposits in North America, something having to do with the shallow Cambrian seas that once covered the entirety of the state. But the mines were deep and dangerous and only the bravest of men ventured into them.

After the salt mine tragedy, Nona was penniless but proud, foraging for food in the forest to feed herself and her wee child. They moved into a straw hut abutting the tail end of the Appalachian mountain range. It was all they could afford.

All Nona had was an old milk cow, named Deuce, and Deuce was about a day away from becoming their last supper when Nona had an idea. Ever resourceful and with a will of pig iron, she became a milk lady. In the beginning she only had enough milk to service a few homes, delivering it in old tin cups. But after making her first few sales she upgraded, got a cart, some bottles, and before the sun was up she loaded the cart full of as many bottles as she could, pulled by the source of it all, Deuce. With her profits she purchased another cow, and another, and soon she became the most popular milk lady in town; but then again she was also the only one.

Even though she was making enough to feed herself and young Ewing, she was still too poor for a tree, and their hut — one tiny room, shoebox-small — was too teeny for even a shrub. But as she was reported to say right from the start, “We do what we can with what we might have.” She said it in the way that people who come from nothing say that sort of thing, all matter of fact, followed by a brief shrug of the shoulders.

So this is what happened on Christmas morning. Nona took Ewing off into the forest, pulled on a cart by the ever-loyal Deuce. And there they sat beneath the tallest, most majestic pine in the forest, an ancient giant of the Pinus clan, a tree so big it’s visible from space, they say. And there she would make a prayer, share some milk and give her son his present. As has been told to the subsequent generations of immeasurably spoiled and ungrateful children, Ewing was thrilled with his interesting pine cone or a rock in the shape of a shoe.

But here is what was remarkable about that Christmas, and every Christmas they shared. They never spent it alone. One by one all the animals of the forest would creep up, join them there, slinking out of the forest-dark like shy friends. Deer, raccoons, wild hogs, bluebirds, hawks, turkeys, forest mice, coyotes, snakes, skunks, sometimes even a cougar or bobcat. Nona particularly loved a black bear she called Susie. They’d all keep their animal distance, but close enough for Ewing to see the warm steam of their collective breath. So the Christmas present really wasn’t a pine cone at all, nor a rock, it was the presentation and a celebration of the awesome myriad of life. She was actually giving Ewing the whole world.

I met Nona when I was three days old and she was 101. A week later she died in her sleep and Deuce followed soon thereafter. In honor of her passing no one in town drank milk for a month.

And now to her son, Ewing, my grandfather. Ewing was nicknamed “Dumbo” as a child, due to his larger-than-life ears. He was actually quite brilliant and used his ears to good effect: not only could he wear large hats; he could also hear everything. He could hear an owl sigh. He married my grandmother Lucille when he was but 18 years old, after he fell in love listening to her hum.

Like his mother, Ewing was an inventive and resourceful entrepreneur. Would it surprise you to know that Ewing was the man who invented the boiled peanut stand? This is almost a true fact and let no one tell you different: the very first ever. He built it out of pallets and tree branches, using rusty nails pulled from old barns, and set it up on the side of the busiest road out of Cullman, a meager dirt road that disappeared after a hard rain and had to be repaved with more dirt next time the sun came out. His peanut stand was the most modern thing around at the time and people went no matter if they liked peanuts or not.

Peanuts grew wild in Cullman. An underground forest of them in Ewing’s backyard became an underground goldmine. The first stand was a great success — boiled peanuts from a roadside stand! What a concept! — and that success led to a second, a few miles down the road. He hired his cousins and cousins of cousins, friends of his cousins and their sons and daughters and soon the stands were everywhere, from Alabama down through Mississippi, sweeping into Louisiana and Florida, up through Georgia and finally into the Carolinas. Very few people know that most boiled peanut stands back then were franchises, but that’s what they were in the beginning. A little part of every peanut sold found its way back to my grandfather’s pocket, and though he never became a rich man he was able to move his bride Lucille out of the thatched hut and into a proper house in town.

Christmas was a magical time in my grandparents’ home. My father got all kinds of presents: peanuts, tiny cars made of peanut shells, and best of all, peanuts painstakingly carved by Lucille, intricate portraits of Washington and Lincoln, or detailed landscapes of the French countryside, all from her imagining what it might be like. Find one today and it’s worth more than a Fabergé egg. Alas, most of them were eaten.

Lucille and Ewing saved and saved and eventually built an actual restaurant serving a great variety of foods. It was the only restaurant for 50 miles in any direction. Some people had never seen a restaurant before; many weren’t even familiar with the concept. Ewing and Lucille had to teach them to use a menu and then how to order their food from the lady in the pale blue frock. The good citizens of Cullman and beyond caught on quick.

People take restaurants for granted, but they shouldn’t. Restaurants are everywhere now, sure. But it wasn’t always like that. You may have my grandparents to thank for that. Maybe not.

With boiled peanut money my grandparents bought a house big enough for a tree and had money at the end of the year to buy something for my dad, Eron, their only child. One Christmas morning my father got a pocket watch. On another he got a knife. The next, a bulky jacket, and then a pair of shoes — three sizes too big, for growing into. On his 16th Christmas they gave him a suitcase, on his 17th a compass. He saw where this was going. Year after year he had gotten one single thing until he got all the things he needed to make a life of his own and when he was 18 years old set off for the wider world.

On his first Christmas morning alone my father woke before the sun came up, fell into the Mississippi River and floated 200 miles down stream to the Gulf of Mexico on a raft hastily assembled from twigs and mud grass, and was finally rescued by one of the bravest and most intrepid sailors ever to roam the Gulf of Mexico in an old shrimp trawler: Joan Pedigo, the woman who would become my mother. They fell in love in about three-quarters of a second.

Family followed almost as quickly: me and three sisters, dogs and cats and a snake and a bird. Still: struggling. Lots of mouths to feed. It was my mother who had the idea for the salted peanut, which brought the two biggest industries in town — salt and peanuts — together for the first time. How no one had thought of it before her was a mystery. Thanks to the salted peanut for a period of years we were a family of not insignificant wealth. Later, a bigger company, the one that made complimentary peanuts — really nice people, for the most part — would put us out of business. But until then every Christmas we traveled to a different country in the world. We’d plan our trips out beginning on January 1, studying the language, the mode of dress, learning their customs and histories: Mongolia, Argentina, Gabon — you name it. One cold Christmas we spent with Eskimos in Greenland. Atelihai means hello, but that’s all the Inuit I remember. Because of my parents and Christmas our family has been almost everywhere there is to go. Name a place.

Yep. Been there.

Name another.

Been there too

• • •

Christmas! Christmas seems made for tall tales: look at the big red one that persists to this day. These days our own Christmases aren’t quite as big as the ones that preceded it — no bears, I am sorry to say — but they are just as beautiful: North Carolina, where we have lived for the last 40 years or so, makes sure of that. Until this year for decades running my family has produced postcard-worthy Christmases: the tree, the lights, the boxes wrapped in shiny paper, all of us gathered together next to the hearth beneath what felt like a dome of warmth and love.

But Christmas is not the same this time around. The pandemic has put a chink in our plans. Our clan is distant and scattered, and we do so many things in the world: we’re lawyers, doctors, construction workers, stage designers, Navy men and women, judges, paralegals, writers, scientists, artists, animal trainers. Every one of us knows a little bit about something, and together — could you bring us all together — we’d know practically everything. My second cousin is training snow-white pigeons to fly back and forth between our many homes, carrying Christmas greetings; another is perfecting the hologram, so even if we’re not together we will look like we are.

But then I think back to Nona, and those misty mornings she spent beneath that towering pine, with mountain lions and turtles, et al; of my father, floating down the Mississippi clinging to a twig and a blade of grass. Which is just to say that yes, Christmas will be different this year, but it’s different almost every year, in one way or another. It’s what Nona said: We do what we can with what we might have: to hope and work for better times while making these times the best they can possibly be. That may be the story of our Christmas this year, but it may also be the story of all our lives.

Written in its entirety at the O. Henry Hotel, Greensboro, NC.

Daniel Wallace is author of six novels, including Big Fish (1998) and, most recently, Extraordinary Adventures (2017). His fourth novel, Mr. Sebastian and the Negro Magician, won the Sir Walter Raleigh Prize for best fiction published in North Carolina in 2009, and in 2019 he won the Harper Lee Award, an award given to a living, nationally recognized Alabama writer who has made a significant lifelong contribution to Alabama letters. He lives in Chapel Hill where he directs the Creative Writing Program at the University of North Carolina.

Poem December 2020

Worksock

If I could round up stockings

I’d take all the holey ones from Mama’s box of sewings,

My father’s, first, the heel ragged as a monkey’s face.

I’d hang that sock again for him

And pray Santa would put an orange

Or some nuts down in the thin

And frayed toe, then arrange

One real coconut with peeling skinned

Off to let him know

The love he held for me I hold for him.

We were not poor — just didn’t have much money.

Christmas meant longing:

That chance to fill me with sunny

Trances when I would skip the fields

And pray for days that Jesus would not appear.

I was never ready to see Him

Alive instead of in a sermon nailed to a dogwood tree.

Before sunup on Christmas day

The plankhouse hummed with joy.

In my stocking: raisins, a few English walnuts, toy

From a Cracker Jack box I’d run

A store with: I’d “sell” my brother a Mary Jane

From his sock that Mama darned in a ray of sun.

— Shelby Stephenson

Shelby Stephenson was North Carolina Poet Laureate

from 2015—2018. His most recent book is More.