Memento Mori

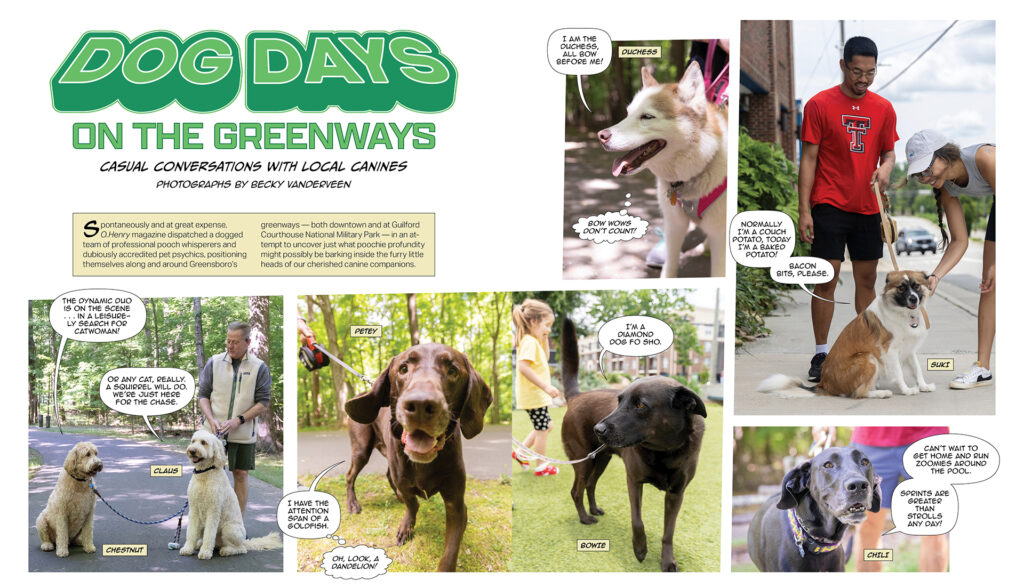

Memento Mori

The affirming life of Leslie Deaton

By Cynthia Adams

Photographs by Amy Freeman

“The ache for home lives in all of us,” wrote poet Maya Angelou. “The safe place where we can go as we are . . .”

For Leslie Deaton, sanctuary is a Dutch Colonial in the historic Fisher Park district. “My story is one of breath-stealing tragedy, but also love in its wildest form, of soul-crushing pain and new mercies every morning,” she says. On leave as a Northern Guilford High School counselor, she’s fighting cancer while drawing comfort from her beautifully realized retreat.

The home, a slate-gray charmer, tells a visual version of Deaton’s story. This is a place of meaning, its well-appointed rooms say. Of warmth. Of joy.

As she found it only a few years ago, it was move-in ready, which was a particular boon, after a sensitive and full restoration by Dunleath residents Camilla Cornelius and Stephen Ruzicka.

“The house was built in 1922; it looked great,” she praises. Cornelius, who formerly housed a counseling practice there, presented Deaton with four pages of itemized renovations, including specialty faucets.

It was a turnkey home with curb appeal, given the on-trend gray exterior with crisp white trim. “So perfect for me,” Deaton adds, having bought the property in August 2020, “in the heart of COVID.”

She made the move well before she became ill, and a year before she lost her only child, William Walton Finch, at age 23.

“Losing my son . . . ” she falters, explaining. “He took a Xanax that was pressed with Fentanyl on July 28, 2021. I believe that is why I have cancer. I just could not endure it.” She pauses. “The love of my life. My only child.”

Her son graduated a semester early from N.C. State University with magna cum laude honors, she adds. Nothing fit.

She sighs raggedly. Tears fall.

Deaton understands those tears are therapeutic and necessary. Ironically, she has seldom been able to enjoy much leisure time at home prior to her illness, given a busy professional life.

Fueled by her longtime work with young adults, she has continued to speak to students and anyone who will listen about the lethal threat street drugs pose to young people, even after a shocking diagnosis last year.

She believes “the trauma of losing Will opened me up to invasion. Losing a child is a different type of loss.” Losing an older child is no less challenging, she says. “It’s different.” Two people in her life who lost children subsequently “ended up with breast cancer.”

In February 2023, she chose to share her son’s story with 700 students, parents and educators at Northern Guilford. She was joined that night by Amy Neville, a California parent who lost a 14-year-old son.

“Tragedy would hurl me without warning into a spotlight I never in a million years asked for but felt required to assume in order to tell the most soul-crushing story of my lifetime.”

Publicly, she drew back the curtain on pain following the loss “of my sun, my moon and all my stars — my beautiful son and my only child.” The title of her presentation? One Pill Can Kill.

In a televised interview with WFMY-TV, Deaton shared the nature of her personal trauma. “I got the absolute worst phone call of the human experience. I was informed that I lost my child to a horrific poison, Fentanyl,” she explained

She met Jane Gibson at Authoracare while grieving.

“I was touched by the love and the pride she shared with me about her son,” says Gibson, a recently-retired staff member. “And despite her great sorrow, she was not crawling away into a hole.” Even though it was a busy time in the academic year for her and her students, it was clear to her that “she would find healing by providing counseling support for these teens. What an amazing, loving woman!”

As long ago as 2022, Deaton began experiencing persistent stomach pain. Late that year, nagging back pain worsened.

“I was trying so hard to resist painkillers,” she recalls. “To honor what I’d been so vocal about.” Instead, she bought a new mattress to help her back, still suspecting she also had a stomach ulcer.

“Then we got new office chairs. Each member of our counseling department had back complaints . . . But guess what? I still had agonizing pain.”

She turned to Ibuprofen, Tums and a heating pad in order to make it through the work day. “One morning in May [2023], our well-intentioned counseling secretary stood at my desk and said, ‘I’m not going to move until you call the doctor.’”

Deaton eventually capitulated, seeking help. When a radiology interventionist proposed a nerve block to alleviate back pain, she tried it.

It helped briefly. Then her pain roared back.

During follow-up, her blood work was normal. But an endoscopy and a CT scan detected a large mass in her pancreas.

Deaton was diagnosed with stage four pancreatic cancer on May 31, 2023. “I was told to get my affairs in order while I still had cognition.” When she learned her diagnosis, she was at home alone. It was a phone call “that cruelly propelled me off my axis once more.”

“Yes, I know I have a terminal diagnosis, but I don’t know what that means,” she says calmly, gazing out a kitchen window. “I could be in a car wreck today,” she says unemotionally. Outside, colorful plants await planting in a garden she plans to call “Will’s Garden.”

She makes plans and continues home projects.

“I’ve not asked my life expectancy from my doctors, and the reason I haven’t is, I feel it’s a guess, at best. I’m focused on today. Today is a gift,” she muses. Shortly after her diagnosis when she realized she wouldn’t be going back to work in the fall, she recalls deliberating over “this silly little rug from Ballard Design. And my friend, Jane Harrill, was here. And she said, ‘You’re going to be here a lot. If that rug gives you happiness, get it.’”

Harrill is Will’s former kindergarten teacher, explains Deaton, as well as an artist. She helps Deaton following treatments.

Deaton’s close, longtime friend, Todd Nabors, who met her at First Presbyterian church, agrees with Harrill.

“We’re the same age,” he says. “We’ve been friends forever.” They see each other nearly every Sunday. Deaton admires his aesthetic and relied upon his point of view when it came to her home.

Nabors, who works for furniture company Thayer Coggin and also consults on design, offered similar advice. “Beauty matters,” he told her.

And so, Deaton ordered the sisal rug.

Deaton has always found “feathering her nest” therapeutic. Years ago, she frequented Summer House, a home decor shop. There she met Kaylee Phillips.

Phillips, who now works in antiques and collectibles at Carriage House, says, “She collects beautiful things. And along the way, she collects beautiful friendships.”

“Beauty does matter to me. And surrounding myself with joy and cheer is a medicine of sorts. It’s a therapy. It’s treatment,” says Deaton. There’s sorrow here, too, of course: the elephant in the room, as the expression goes. Yet there’s an aura of peace, too, and light. It streams through the house’s many windows.

At home, the gentle colors of a spa surround her.

Along those lines, she has selected a fabric with which she wants to reupholster an upstairs den chair. The room is softly feminine, accented with the pastel art she collects. Inside sit her desk, a vintage French chair found at Carriage House, along with a television, chaise lounge and cushy seating. After treatments — a more aggressive regimen of chemo and radiation began in April — she often rests here.

She cocoons here in the beautiful room, sometimes tossing a toy to her dog, Charley, whom she shares with her dad, and Virginia, her cat.

She resists staying in bed when under the weather, and refuses to recover in pajamas but prefers regular clothes. To be as normal as possible. “When I go to treatment, they say, ‘We love seeing what you come in wearing.’” Deaton takes pride in this, saying it is a form of self-care.

Even while wearing yoga pants, she stacks delicate beaded bracelets along her arm — many are gifts from devoted friends.

She refuses to give in or stop making an effort.

This applies equally to her personal environment.

She has just chosen a new fabric by Elliston House for a favorite bedroom chair. “The company is owned by [Greensboro residents] Morgan Hood and Ally Holderness. And I just admire them for taking that leap of faith,” she says of their venture into business.

“At times I’m tethered to that chair.”

She chose Elliston House for Roman shade fabrics in the same space and the company’s wallpaper to line a breakfront she uses for storage. She’s deliberating another Elliston House fabric for an often-recovered armchair.

She, perhaps, values art and personal mementos above all else. Art is present in every room, as are personal touches. Many of the works she’s acquired have been created by local and regional artists.

Winston-Salem artist Carolyn Blaylock is a favorite. She collects North Carolina artists Bee Sieburg, Libby Smart, Sharon Schwenk, Sue Scoggins, Helen Farson, Amy Heywood, Yvonne Kimbrough, Crystal Eadie Miller and Murray Parker. She describes their styles as “warm and inviting.” She treasures pieces by artist (and fellow educator) friend Harrill.

Virginia artist Martha Dick and Georgia artist Lisa Moore are also part of her collection.

Favorite places and influences?

Deaton admires the Carolina Inn, in the “most classic of ways.” (She’s a UNC-Chapel Hill grad.) She loves “going room to room and seeing the differences.”

Home magazines are a constant source of inspiration. She again mentions former home decor shop Summer House. “It had a great influence. I loved it.” She uses painted pieces acquired there, including chests and breakfronts.

Once, a man delivered something to her prior home and exclaimed, “You’ve shopped at Summer House!”

“Everybody who’s ever encountered her loves her,” says Phillips, musing about the friendship that originated in that store. “We’ve all become friends with her. It was deepened due to the connection with our children,” she adds.

Often, too, Deaton finds Randy McManus’ floral shop “very therapeutic for me.”

She picks up a small plate displayed in her den, found in a Pawley’s Island shop in 2019.

“It simply says, ‘Tell stories.’ It’s funny because I didn’t buy it initially, but it popped into my mind several times before our departure, so I scooped it up on our way out of town, never dreaming of its significance, completely oblivious that it would ultimately become my life’s theme song.”

Deaton still considers her home a creative outlet and she now has time to contemplate every detail. She considers a colorful pink Elliston House lampshade. (Pink is a favorite color. There is even a pink Keurig coffeemaker on the kitchen counter and a pink leopard print sisal on the kitchen floor).

She just replaced the upstairs bath’s colorful mirror with a high gloss white-framed one. Satisfied, she says it calms the effect of a lively wallpaper.

This is part of “living my life,” she explains. Design, color and beauty bring her great joy.

When Deaton walks into her son’s former bedroom, her voice is softer. “His special, special things,” she says quietly. “I just had to totally redo it . . . ”

She pauses, as if she is seeing the room as it was before it became a guest room, adding a white Matelassé coverlet, crisp linens and French blue accents. One wall displays diplomas, pictures and mementos from her son.

Everything in here is something about Will, she says.

After his dad left when he was young, Will and his mom had years together. “We had such a unique and special relationship. I weep. And I will never stop weeping. I tell people, I do not cry over my cancer, but I cry over Will.”

She reads aloud framed stickies he wrote to her, struggling with her emotions.

“I have beautiful portraits of him,” she says of her son. “I am so thankful.”

Friends who know of Deaton’s loss and health issues have donated wallpaper, fabrics, bedding, a specially monogrammed neckroll with Will’s initials from Matouk bedding — even a special commission by Triad artist Amy Heywood.

“She gave that [painting] to me. Came into the home, looked at all my art. And that’s what she created.” Fresh flowers appear at her doorstep. Letters with donations arrive from strangers.

“Never did I dream when I redid this room that so many different people would be using it to stay with me,” she continues, lingering in Will’s former room. She is pleased when they tell her they find peace here.

If memories of Will are the dominant focus of her home, the underlying theme is serenity.

The lighting fixture in her room was a gift from a friend. “It’s a very visual comfort,” she says. “It’s so beautiful at night.” This is a real place of sanctuary, she repeats.

She picks up and cuddles Virginia, the blue-eyed rescue cat. “She has a little dot on her nose,” Deaton says delightedly. She imagined her “walking up Virginia Street. to find me.”

Deaton rehabilitated her. She is epileptic, Deaton says, and takes phenobarbital; once, a well-meaning friend almost gave her Virginia’s medicine. She winces, but smiles, quipping, “Wonder what that would have been like?”

The downstairs rooms are tasteful yet casual with cream-colored walls, accented with French finds, collections and artwork. The eating nook off the kitchen had original benches and table, which she decided to keep but stash in storage. It was original, and Deaton says she didn’t want “to be disloyal to the Ruzicka’s renovation.” While she would “never get rid of it,” she stored it in the basement so she could add a table that better worked for her 6’3”-tall son when he lived with her.

Each room in her home sparks a return to the subject of her son.

Will chose to enter treatment at Fellowship Hall, she says quietly, standing in the breakfast nook where they ate together when he was staying here.

He had completed treatment for addiction. Will had just qualified for Navy Seal training, “when this all happened.” Deaton would never know if it was his first relapse either. At the time, her son was living in Charlotte and doing incredibly well, according to his roommate. He had, for months, endured miles of running and swimming. “He doesn’t fit the mold,” she stresses.

Nonetheless, Deaton extols the virtue of a recovery program. “But when you are 22, and everything about socializing is a drinking event . . .”

Alcohol, she explains, lowers our inhibitions. “And opioids are the worst. Instantly addictive. I’m not minimizing alcohol,” she stresses, “but it’s a different beast.”

“It’s a tragic, tragic story,” she says. “An incredible, stinging hurt and [emotional] pain followed him,” she says. “But Will was definitely trying to find a way to deal with that pain. And he went at it the wrong way.”

“But he was always outstanding, and he will always be my greatest accomplishment,” she says.

Coping with extreme pain, Deaton has had to learn how to handle her own fears regarding painkillers. She credits the Palliative Care Program at Cone for guidance.

“Dr. Beth Golding took me under her wing and has gotten control of my pain,” says Deaton. Controlling pain enables her to walk again, go to the grocery store, to do chores. “Transformative,” she adds.

She recalls Dr. Golding saying “we don’t see thriving in pancreatic patients. But you are doing life.”

With Deaton’s pain lessened, she occasionally found diversion working a few hours at Watkins Sydnor, a home store. Earlier last year, she even managed 5-mile walks from Fisher Park to Irving Park, feeling completely energized.

“For me, time with my friends is what matters. It’s not about stuff. Funny, because this article is about stuff, in a way. But what this disease has taught me is that time together is all that matters.” OH