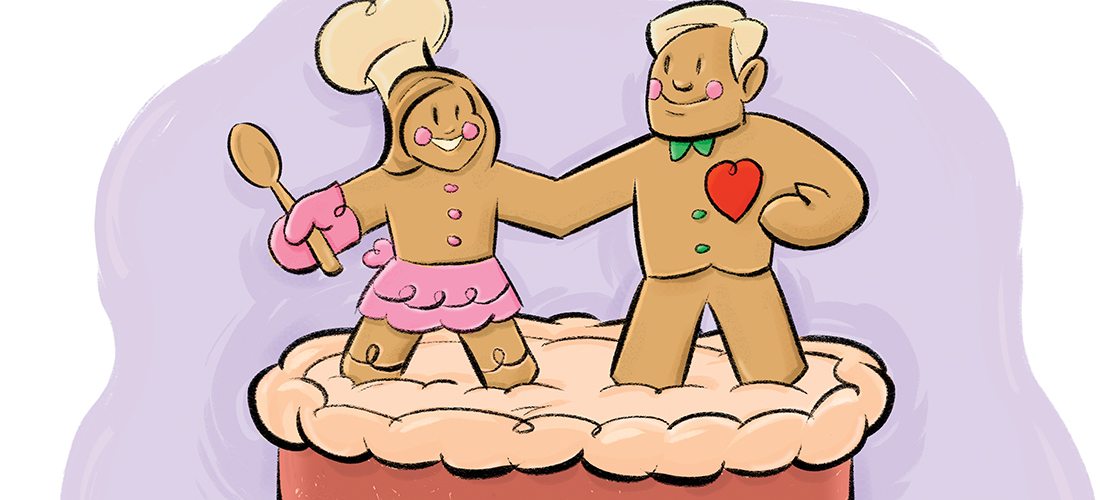

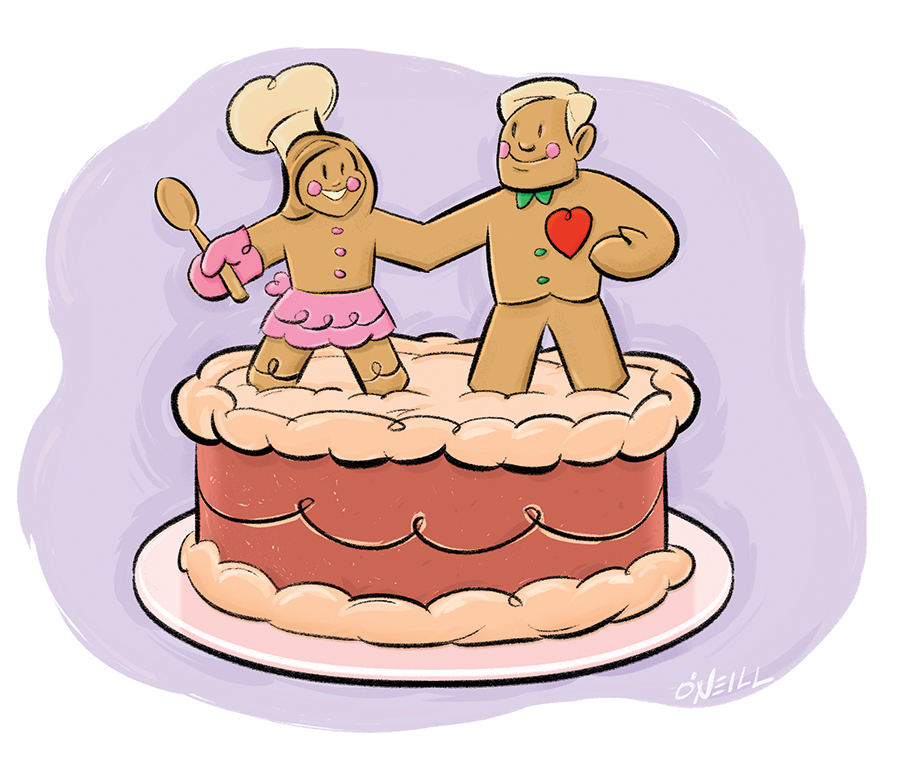

The Baker’s Assistant

How sweet it is

By Jim Dodson

Not long ago, my wife, Wendy, joined 47 million foot soldiers of the Great Resignation by retiring early from her job as the longtime director of human resources for one of the state’s leading community colleges.

She loved her job at the college. It was fun and fulfilling in almost every way.

But something more was missing — and revealed — when COVID invaded all our lives.

Simply put, it was time to follow her heart and do something she’d envisioned doing even before I met her 25 years ago: to start her own gourmet, custom-baking company called Dessert du Jour.

News late last year that an innovative shared community kitchen for food entrepreneurs (called The City Kitch, based in Charlotte) was opening branches in Greensboro and Raleigh propelled her into action. She signed up for the first private kitchen studio and got to work preparing for her debut at a popular outdoor weekend market just before Christmas, selling out everything she baked in a couple hours. It was a promising start.

I should pause here and explain that Wendy is no novice or newcomer to the luxury baking world. Even while masterfully holding down a demanding career over the past two decades, she made stunning custom wedding cakes, luscious pies, artistic cookies and other baked delicacies for friends and neighbors.

As I say, she was already wowing customers in Syracuse, New York, when we met during one of my book tours in 1998, and she agreed to go on a formal first date that turned out to be, as I fondly think of it, baptism by baby wedding cakes.

To briefly review, on a brisk autumn evening after a seven-hour drive between my house in Maine and her home in Syracuse, I arrived just in time to find Wendy cheerfully boxing up 75 miniature, exquisitely decorated wedding cakes for some demented daughter of a Syracuse corporate raider.

“Oh, good,” she beamed, flushing adorably with a dollop of icing on her button nose, as I appeared. “Want to help me box these up and take them around the neighborhood for me?”

How could I refuse? Her neighbors, it seemed, had offered space in their refrigerators and freezers until the cakes could be delivered to the wedding hall in the morning.

Truthfully, I don’t recall much about being pressed into service as an impromptu delivery man. I just have this vague memory of carefully boxing up dozens of the beautiful little cakes and bearing them all gussied up with elegant ribbons and bows to her lady pals around the cul-du-sac. “Oh,” one actually cooed as she looked me over. “You must be the new boyfriend from Maine. Careful you don’t put on 50 pounds. Wendy’s cakes are awesome.”

I gave her my best Joe Friday impersonation. “Never tasted ’em, ma’am. Just here to help out the baker lady.”

Happy to report, the baby wedding cakes made it safely to the wedding hall the next day without incident. The grateful baker lady even thoughtfully saved one of the gorgeous little cakes for the trip home to Maine.

I’m embarrassed to say I never sampled it. Cake wasn’t my thing, probably because I grew up with a mama who annually made me a birthday cake from a Betty Crocker box mix and store-bought frosting that tasted like chocolate-flavored sawdust with icing. I gave Wendy’s baby wedding cake to my children, who absolutely loved it.

Another issue emerged on my next visit to Syracuse, our critical second date. When I breezed into her kitchen with a bottle of her favorite wine before we went out to dinner, I found her putting the finishing touches on another masterpiece of the baker’s art.

Sitting nearby on her kitchen counter, however, was a beautiful wicker basket full of popcorn, my all-time favorite snack food. As she opened the wine, I grabbed a big handful of what I thought was popcorn.

Her lovely face fell. It turned out to be a groom’s cake that only looked like a wicker basket full of popcorn.

Profusely apologizing, as I licked the evidence of the crime off my greedy fingers, figuring this might be our last date, I had something of a dessert awakening.

“Hey, this is really good. I don’t even like cake. What’s in this?”

To my relief, she laughed. “Only the finest Swiss white-chocolate, sour-cream cake with salted buttercream. But no worries. I can make another one pretty quickly. Let’s just get Chinese takeout for dinner while I work.”

I’d never seen such composure under fire. Right then and there I decided to propose to this remarkable woman and even confessed my sad history with Betty Crocker, wondering if she would do the honor of becoming my wife and someday making me a birthday cake.

“Sure,” she said. “I’ll even make you a Betty Crocker box cake if you want it.”

Talk about a selfless act of love! This was like inviting a Wine Spectator judge to enjoy a lovely bottle of Boone’s Farm’s Strawberry Hill or LeRoy Neiman to do a doodle of a racehorse! She actually made me a box-mix cake, which I took one taste of and dumped in the garbage.

Fortunately, by the time our wedding rolled around two years later, Dame Wendy had schooled me up like a pastry chef’s apprentice, a culinary awakening sealed by my first taste of her incredible old-fashioned caramel cake — which she now makes me every year for my birthday (along with a sour cherry pie).

Not surprisingly, the spectacular cake she made for our outdoor wedding beneath a gilded September moon disappeared without a trace before I could even get a taste. Our greedy guests left nary a morsel and even took home extra pieces stuffed in their pockets.

Since that time, a long and steady stream of fabulous specialty cakes, cookies, pies, scones, muffins and the best cinnamon rolls ever made have flowed from her ovens to the tables of friends, family and customers from Maine to Carolina.

Which is why the creation of Dessert du Jour is such a milestone for the love of my life. She’s never been happier, launching her little dream company at a time we’d all like to see in the rearview mirror as soon as possible. In the meantime, she shares her happiness with others, one gorgeous theme cookie or slice of roasted pecan-studded carrot cake at a time.

And for the moment at least, I have the honor and pleasure of still being her sole employee, the one who puts up the tent and tables at the street market and delivers the goods wherever I’m sent around town, a baker’s assistant happily paid in cake tops and leftover cinnamon rolls.

I ask you, does life get any sweeter than that? OH

For more information, visit thecitykitch.com and dessertdujour.net.

Jim Dodson is O.Henry’s founding editor and ambassador at large.