Omnivorous Reader

Omnivorous Reader

Heart of a Poet

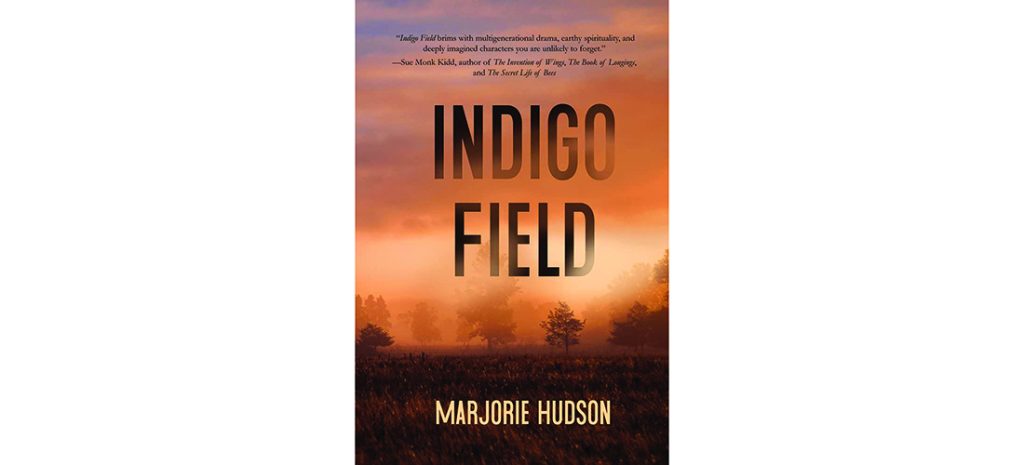

Time, place and eternity meet in Indigo Field

By Stephen E. Smith

On this sunny late-March afternoon, Marjorie Hudson occupies rarefied space: She’s standing in the footprints of F. Scott Fitzgerald, Sherwood Anderson and Thomas Wolfe, reading from her beautifully wrought first novel, Indigo Field, at the Weymouth Center for the Arts & Humanities. Her bright eyes (they might be blue or green; the afternoon light plays tricks) stare out from a shock of white hair (she’s accurately penned the description, “white-blonde hair,” for a character in her novel), and she’s smiling the smile of one who’s realized her dream via pure, implacable determination. In the words of Keats, she’s surprised everyone, including herself, with “a fine excess,” writing that strikes the reader almost as a remembrance. Now all she has to do is sell her masterwork. The literary world needs to know about Indigo Field, and readers need to snatch it off bookstore shelves or download it online.

Hudson is a Midwesterner who settled in North Carolina by way of a lengthy sojourn in Washington, D.C., where she worked for a nature magazine that kept her indoors much of the time. “We all worked such long hours, we hardly got to go outside,” she says. “All it took for me to jump ship was a visit to a friend (in North Carolina), a rainbow over a farmhouse, and I was hooked. My days were full of freelance writing assignments, sunbathing in the yard, gardening and pond swimming. Whippoorwills chanted outside my window, a sound I’d never heard before. When frogs took over the pond one night in a massive mating ritual, it was better than any nature documentary.”

Thus Indigo Field evolved into a decidedly Southern novel featuring Southern characters immersed in a regional history that emphasizes a strong sense of place. Even so, there’s no forced, ersatz Southernisms in her dialogue, no Hollywood “y’alls,” and, thank God, there’s not a subhuman Faulknerian Snopes in sight. Her characters speak authentically, and they never propagate a phony gesture. Somehow she’s acquired the ability to absorb the Southern landscape she’s adopted as home.

She came by this invaluable knowledge by happening into the perfect job. “One of the many freelance jobs I took to pay the rent was copy-editing novels at Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill,” she says. “I had never read much Southern lit before, and reading the novels of Clyde Edgerton and Jill McCorkle, and the stories of Lee Abbott and Larry Brown was like going to grad school. How a novel all fit together was fascinating. How a short story was constructed was beautiful. And the language! I was learning the rhythms of speech and turns of phrase from my neighbors, my new husband and these stories. I turned to my computer and started a story of my own.”

Hudson’s prose style is clear and concise, and she preserves a delicate balance of empathy for characters who come alive with startling authenticity. Her leapfrogging plot turns sustain the story’s energy and propel the reader ever forward. The Regal House Publishing promotional material provides an accurate precis. “In this novel of moral reckoning, the unjust outcome of a murder trial, and the chance accident that follows, result in a feud that raises the spirits of the dead, forcing enemies to become allies in order to survive.”

Good enough. But the novel’s beauty is more than fancy footwork, deft plotting and the able handling of points of view. Hudson writes with the heart of a poet. Her prose has been worked on (in the best sense) to get rid of that worked-on feeling. Take this transitional passage from Chapter 49: “This great wind rode the eye of a rogue hurricane and spun out lightning and whirlwinds like warriors of a great army. These warriors flattened all they touched, and chose what they touched with care. They touched the new homes of wealthy people and left the old derelict homes of Poolesville, the farmhouses of widows, the trailer parks of the destitute, damaged but still standing. The wind brought lightning strikes so pervasive that many small fires lit rooftops, tall trees and last year’s broomsedge in Indigo Field. . . . This wind skipped from high spot to high spot, so that places that had been raised up were laid low, and places that were low and humble remained intact.”

The writing of Indigo Field took up almost 30 years of Hudson’s life — with time out to write and publish an acclaimed short story collection, Accidental Birds of the Carolinas, and a history/travelogue, Searching for Virginia Dare. “I had 450 pages (of the novel) by 1998, but I didn’t know how to end it and I knew it needed revision.” She set Indigo Field aside, finished a different novel, sent it out, got discouraged, went to graduate school, and all the while the novel kept getting longer and longer. Hudson recalls: “I kept adding layers of things I was fascinated with: parrot colonies, Nike missile sites, archeology. As it got longer and longer, unbeknown to me, New York’s acceptable novel length had gotten shorter and shorter. It was roundly rejected.” So Hudson turned to a small press, Regal House Publishing in Raleigh. Regal reminded her of Algonquin in the old days: “Small, feisty, locally owned. I even knew one of the editors,” she says. “I submitted my 50 pages. They asked for the rest. I got the call a couple of months later. I was still revising. Cutting mostly. I had a whole new version by the time Jaynie called and said ‘Yes.’”

Indigo Field was chosen to be part of Regal’s “Sour Mash Series,” a selection of books centered on the American South’s sense of place and history. Hudson was in the place described by Flannery O’Connor: “The Southern writer operates at a peculiar crossroads where time and place and eternity somehow meet.” After living in North Carolina for almost 40 years, Hudson is a Southern writer, and she’s pretty proud of that.

She’s come a distance, a far piece, to stand before an audience at the Weymouth Center — and all the other audiences she’ll be entertaining in the months to come. She has a novel to sell. It’s demanding work, but Marjorie Hudson is surely up to the task. OH

Stephen E. Smith is a retired professor and the author of seven books of poetry and prose. He’s the recipient of the Poetry Northwest Young Poet’s Prize, the Zoe Kincaid Brockman Prize for poetry and four North Carolina Press Awards.