How the historic Guilford Building was reborn as the

most wired structure in downtown Greensboro — and possibly the South

By Billy Ingram • Photographs by Amy Freeman

Shortly before midnight on April 13, 1985, the 200 and 300 blocks of Davie Street, both to the east and west, were almost entirely engulfed in flames. Construction materials located in front of Greensborough Court and directly behind the Guilford Building were fueling much of that conflagration while simultaneously raining fireballs on severely overwhelmed firefighters. Raymond Holliman was one of the men assigned to protect the Guilford Building on the corner of South Elm and Washington, knowing that if they failed to hold the line, commanders on the ground were prepared to move their troops and equipment back to the Carolina Theatre and allow Hamburger Square to burn unabated. Firefighters were successful in their heroic effort, but what Holliman couldn’t know then was that, within a few years, he’d be one of the owners of the very high rise he was instrumental in saving.

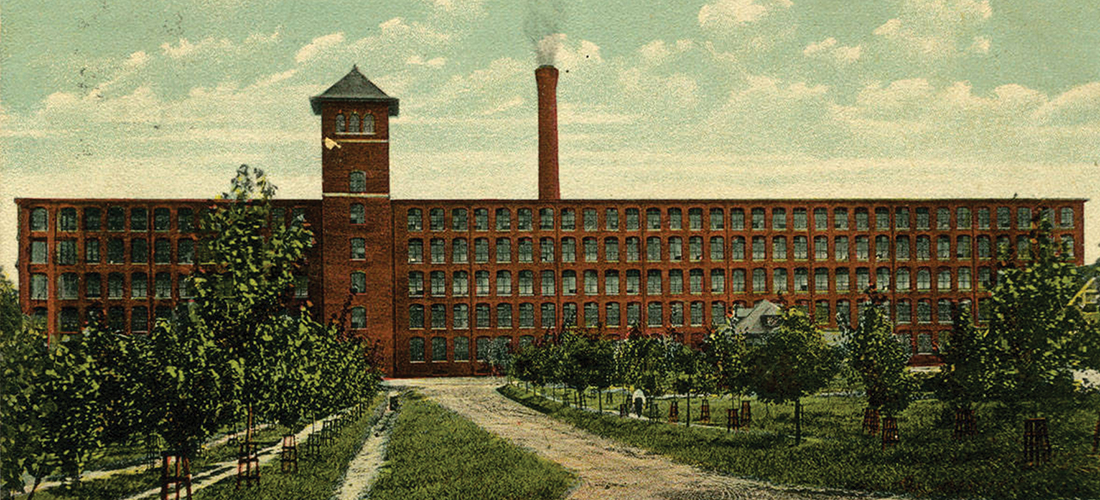

Downtown Greensboro was expanding skyward in 1927 when the opulent Guilford Building opened for business. Jefferson Standard’s headquarters had been completed four years earlier. Both skyscrapers were the work of architect Charles C. Hartmann, who outfitted this, the second tallest building in the city at the time, with an exterior consisting of a bold gray terra-cotta base, scored to resemble marble, with the upper floors wrapped in locally sourced brick, all crowned with an impressive terra-cotta cornice.

No one disputes that this Renaissance Revival style superstructure was originally envisioned as a hotel, reflected in the sumptuous imported Italian marble lined lobby and hallways on every floor. It’s perhaps apocryphal but at least one old-timer remembers the Guilford Building as the intended location for the King Cotton Hotel — until the owners quickly realized noise and soot from 100 trains a day pulling into the new depot then under construction would make sleeping there untenable. As the story goes, another King Cotton, similar in design but much less fanciful, was erected two blocks away.

A total of 14 levels, each of the 11 upper floors of the Guilford Building encompasses more than 8,000 square feet of office space. The original main floor tenant in 1927 was Greensboro Bank & Trust, a relatively new concern that started on this very block in smaller digs. Unable to withstand the ravages of the Great Depression, it went belly up after depositors panicked and caused a run on the financial institution. It was replaced by United Bank and & Trust in 1931. When United collapsed three years later, Guilford National Bank moved in, hence the current name of the building.

Earliest tenants included R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Company, Smith & Corona Typewriters, Doctors Fred Patterson and Wesley Taylor, Montgomery Ward’s district offices, the Atlantic and Yadkin Railroad, along with numerous cotton and insurance brokers. A number of prominent lawyers practiced at the Guilford, so a fully furnished law library was installed to serve attorneys on site. What is now the guard station in the lobby was first the Hole-In-The-Wall then, beginning in the early 1930s, the Guilford Soda Shop, which continued selling hot dogs and confectionaries well into the 1980s.

During WWII, at least one seedy massage parlor was situated on the premises, no doubt serving the hundreds of randy Army Air Force soldiers being trained and outfitted at the Overseas Replacement Depot, alongside the IRS, the US Office of Price Administration (setting commodities prices during the war), and the folks in charge of the fuel tank farm by the airport.

Future state senator Elton Edwards had an office on the sixth floor in the 1950s; that’s when Coca-Cola was one floor up, directly above that were General Electric and Edgcomb Steel, while Western Auto could be found on the 11th floor. You could also cash in F&S Gold Stamps shoppers collected from the grocery store for appliances and knick-knacks in their showroom, send telegrams via Western Union, and purchase men’s clothing at The Slack Shop.

In the 1960s, NCNB took over the space Guilford National Bank had occupied, while Carlyle Jewelers got underway here as The Jewel Box. Better Business Bureau, WQMG Radio and around a dozen insurance companies had offices on the upper floors. Northwestern Bank moved in when NCNB relocated in the 1970s, installing a side entrance where the National Theatre used to be, while longtime merchants The Slack Shop and Guilford Soda Shop continued to anchor either side of the lobby.

As retailers began their exodus from downtown to the suburbs, the Guilford Building was similarly in a state of flux. Within a decade, this once premier banking and business center was as much a derelict as many other downtown establishments. The skyscraper was donated to Guilford County by Jefferson Pilot, the largest gift in our county’s history, then put up for public auction.

Bob Poston grew up in Greensboro but was living with his wife, Diana, in New Jersey in 1993, running his software business when, he recalls, “My sister and her son Raymond Holliman, who were here, said they wanted to buy the Guilford Building. I couldn’t remember which one it was!” he recalls. “So many people who might have wanted to buy it, didn’t want to touch it,” Bob says, remembering considerable concern about possible asbestos levels. “Fortunately for us, Raymond had worked for the fire department and had been trained in the asbestos problem. He investigated the building and found out there were just a few tiles on a few floors,” all of which were removed.

The Postons figured on being silent partners in the deal. “My sister was trying to talk us into moving down here,” Bob says. “When we came down to visit she showed me this office, it sort of clinched the deal for me because it has so much personality.” Today, Bob is retired while Diana serves as leasing agent, chief financial officer and overall majordomo. “Diana kind of grew into managing and developing.” Bob explains, “The more she did it the more she liked it.”

First order of business was resuscitating the decaying tower, a painstaking floor-by-floor heavy construction job. Only a few scattered tenants occupied offices when the families took possession of the building. Television receivers bouncing signals from mobile news vans to both WFMY and WXII sat on the roof along with a whole lot of other ancient infrastructure with frayed wiring, some of it dating back to the 1920s.

This enterprise was a tremendous leap of faith as Diana recalls. “Those were dark days for downtown,” she remembers. “There was actually a young prostitute out front and drug dealing. It was terrible.” Other than a few disparate watering holes, nobody was seriously looking at downtown to locate any sort of business. Diana adds, “It took vision, mostly from Raymond.”

It turns out to have been fortuitous timing on their part, however, as cell phone use and something almost no one had heard of in 1993, the Internet, were poised to explode. “We had a stroke of luck,” Diana confesses. “Just about the time we were signing the paperwork to buy the building the telecommunications industry started to deregulate.” Rather than just leasing offices as originally planned, she allows, “Early on, I got a phone call from a company in the Midwest and they said, ‘You know, you’re in perfect coordinates for our antenna and, by the way, do you have any inside space we could use for support equipment?’ Then it was one [tech center] after another after another after another.”

The heavy equipment and massive refrigeration units the telecommunications industry employs for switching centers and server farms requires secure locations with maximum load-bearing concrete and steel flooring, qualities the Guilford possesses in abundance. At present, there are some 60 high-tech firms operating within its confines. Familiar communication firms like AT&T Mobility, Sprint/Nextel, and Carolina Digital likely made one of your recent phone calls possible through their sophisticated routers and relays while Web hosting and design firms like Forcefield and Carolinanet provide essential online connectivity. “We call it co-opertition,” Diana says. “They’re in fierce competition but share fiber and battery backups.” Raymond tells me that the backup generator in the basement, two V8 turbo diesels bolted together, “Could run the whole block if we wanted to.” So it came to pass that one of the oldest structures downtown is also the most modern.

Tenants love the building’s retro features: It’s the many original, fully restored details that lend so much excitement to this nearly century-old landmark. Cartoon depictions of General Greene on the elevator buttons, the layout of the offices with interior walls that don’t meet the ceiling and glass transoms above mahogany doors with pebbled glass inlays, imbue these workspaces with an open feeling. “Historic chic, people call it,” Diana notes. “We’ve developed this building all the way, all by ourselves.”

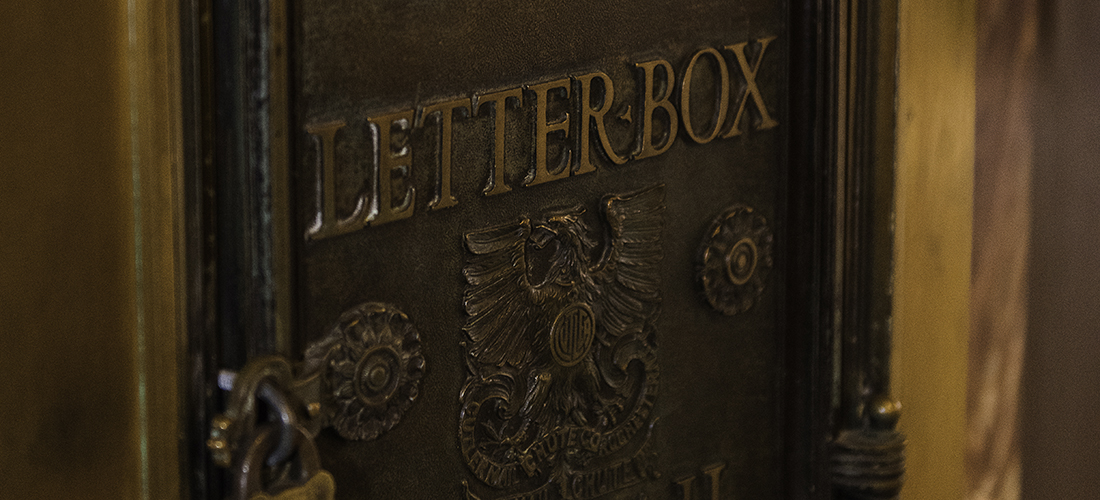

One of the striking features, located next to the elevators, is the brass mail chute that descends from the top floor to the lobby. Diana explains why it’s no longer in use: “One day our mailman was picking up in the lobby and somebody put a sharp object down the chute and it cut his wrist.” That mail apparatus is actually property of the U.S. Postal Service. “The supervisor from the main post office came over and said, ‘I don’t want you to get rid of these but let’s block them.’”

The former bank lobby is right out of a 1930s gangster movie with a giant brass clock; extinct San Daniele Italian pink marble teller stations, baseboards, and two-story pillars; dark wood panel accents; ornately fashioned plaster molding on the 16-foot high ceiling; and rows of picture windows backing the two balconies. Diana tells me, “It was the Roaring 20s and everyone thought there was no end to our prosperity.” Only one of the delicate brass-and-green glass hanging lamps remains. “By the time we got in here thieves had taken the rest. We saw where they might have been auctioned off somewhere but we didn’t get there in time.”

Raymond Holliman points out the circular embedded medallions on the ceiling, which he says weigh around 300 pounds each. “We had a craftsman who worked on the Governor’s mansion come down and he worked on that ceiling for about two years,” he adds. When they were investing all that effort into this dazzling showplace, a five-star restaurant must have seemed like a good fit. And yet, in the end, the space was used for heavy equipment storage by Duke Power and wouldn’t be accessible to the public.

Overseeing reconstruction of the only floor left to develop, Raymond explains the meticulous process they go through: “We take it all out, everything. We take the moldings from around the windows down, remanufacture them, then put them back.” When it comes to the authentic accents, from the individual mail chutes to the distinctive doorknobs, “We go to a great deal of trouble to restore those, get them polished and corrected.” The panorama view is stunning from this 10th-story high perch. Raymond says, “I come up here on July 4th to watch the fireworks downtown, High Point, the water park; you can watch like six fireworks at the same time.” The shot of downtown you see on News 2 is from the top of this high rise.

One of the perks of occupancy is the shared glass enclosed conference room on the mezzanine level, looking out over South Elm, featuring state-of-the-art interconnectivity for every participant no matter what device they’re using. Bob tells me, “There’s free Wi-Fi in this room so if you’re on Skype or FaceTime and have a client in China, you can talk to them and present it on the [wall-sized] screen.”

The row of storefronts lining Washington Street have been home over the last nine decades to beauty parlors, jewelry stores, dentists and optometrist offices, civil service organizations and various men’s clubs. The two longest-running businesses there today are Howard’s Barber Shop and Locke Alterations. When the Hollimans and Postons acquired the building in 1993, barber Howard Cleveland had already been clipping and shaving customers in this location since 1981.

Jesse Locke has even deeper connections to this corner. While studying at A&T University, Locke began working at the Guilford Building performing alterations part-time for The Slack Shop in 1961. He met his future wife, Dorothy, when she was working the counter for Austin “Jimmy” James at the Guilford Soda Shop in 1972 before he relocated his own business here from across South Elm in 1994. He’s kept the city in stitches ever since.

This monument to the optimism of those who came before us, recast as a thriving high-tech portal, is poised yet again to lead us into the future. With the reinvigoration of the South Elm corridor, “We’re almost full. People like being in the middle of everything,” Diana says. “And they like having access to the high speed connections and data we have on site. There’s a lot of networking going on around us.” Ninety years of networking . . . and counting. OH

A native of Greensboro, Billy Ingram enjoys nothing more than writing for O.Henry. Which usually indicates he’s about to get fired.